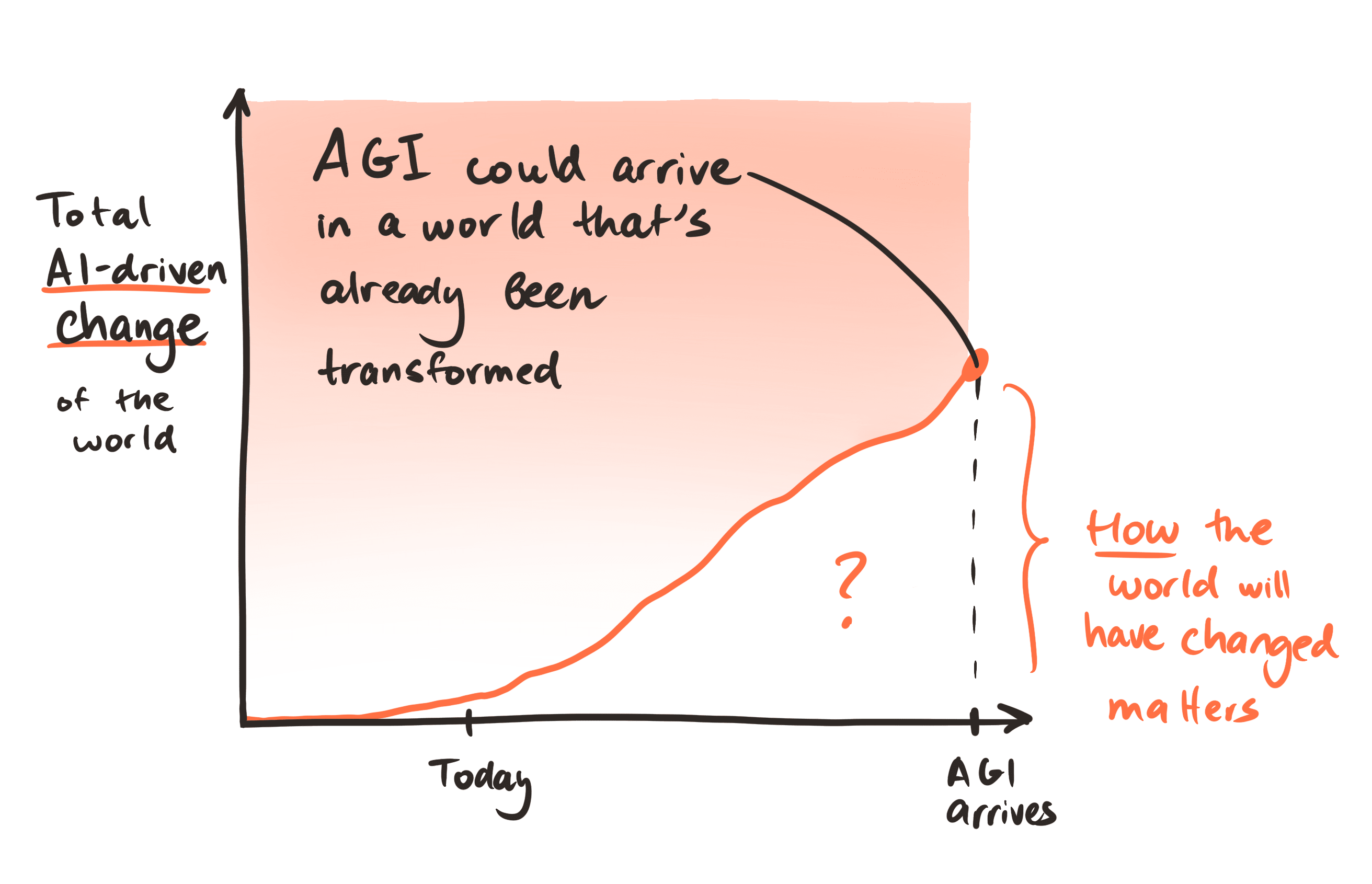

AI risk discussion often seems to assume that the AI we most want to prepare for will emerge in a “normal” world — one that hasn’t really been transformed by earlier AI systems.

I think betting on this assumption could be a big mistake. If it turns out to be wrong, most of our preparation for advanced AI could end up ~worthless, or at least far less effective than it could have been. We might find ourselves wishing that we’d laid the groundwork for leveraging enormous political will, prepared for government inadequacy, figured out how to run large-scale automated research projects, and so on. Moreover, if earlier systems do change the background situation, influencing how that plays out could be one of our best levers for dealing with AI challenges overall, as it could leave us in a much better situation for the “boss-battle” AI (an opportunity we’ll squander if we focus exclusively on the endgame).

So I really want us to invest in improving our views on which AI changes we should expect to see first. Progress here seems at least as important as improving our AI timelines (which get significantly more attention). And while it’s obviously not an easy question to answer with any degree of confidence — our predictions will probably be off in various ways — defaulting to expecting “present reality + AGI” seems (a lot) worse.

I recently published an article on this with @Owen Cotton-Barratt and @Oliver Sourbut. It expands on these arguments, and also includes a list of possible early AI impacts, a few illustrative trajectories with examples of how our priorities might change depending on which one we expect, some notes on whether betting on an “AGI-first” path might be reasonable, and so on. (We’ll also have follow-up material up soon.)

I’d be very interested in pushback on anything that seems wrong; the perspective here informs a lot of my thinking about AI/x-risk, and might explain some of my disagreements with other work in the space. And you’d have my eternal gratitude if you shared your thoughts on the question itself.

Hi Lizka - really enjoyed the article. Often AI development seems to be discussed largely through the paradigm of 'do we speed up to achieve radical transformation, or do we slowdown to reduce risk'. Hadn't thought in depth about before about the notion of aiming to speed up certain components, while slowing others to better manage the transition.

One thought as you go into your more detailed analyses. While you view epistemic first transformation as preferential, you nod to the risk of an epistemic first transformation leading to the risk of being leveraged to mislead as opposed to enlighten the world. Another risk which sprang to mind with an epistemic first transformation is also that it becomes an immensely powerful tool for those with first access (and it feels fairly reasonable to imagine that any major transformation would likely be accessed by government before being implemented in broader society). If a government with authoritarian tendency had first-access to epistemic architecture which enabled superior strategic insight a substantial risk pathway would be that it could be used to inform permanent power capture/authoritarian lock in (even without being leveraged to misinform citizens/public). The technology and impact could in theory never become public.

I'm also worried about an "epistemics" transformation going poorly, and agree that how it goes isn't just a question of getting the right ~"application shape" — something like differential access/adoption[1] matters here, too.

@Owen Cotton-Barratt, @Oliver Sourbut, @rosehadshar and I have been thinking a bit about these kinds of questions, but not as much as I'd like (there's just not enough time). So I'd love to see more serious work on things like "what might it look for our society to end up with much better/worse epistemic infrastructure (and how might we get there)?" and "how can we make sure AI doesn't end up massively harming our collective ability to make sense of the world & coordinate (or empower bad actors in various ways, etc.).

This comment thread on an older post touched on some related topics, IIRC

Basically +1 here. I guess some relevant considerations are the extent to which a tool can act as antidote to its own (or related) misuse - and under what conditions of effort, attention, compute, etc. If that can be arranged, then 'simply' making sure that access is somewhat distributed is a help. On the other hand, it's conceivable that compute advantages or structural advantages could make misuse of a given tech harder to block, in which case we'd want to know that (without, perhaps, broadcasting it indiscriminately) and develop responses. Plausibly those dynamics might change nonlinearly with the introduction of epistemic/coordination tech of other kinds at different times.

In theory, it's often cheaper and easier to verify the properties of a proposal ('does it concentrate power?') than to generate one satisfying given properties, which gives an advantage to a defender if proposals and activity are mostly visible. But subtlety and obfuscation and misdirection can mean that knowing what properties to check for is itself a difficult task, tilting the other way.

Likewise, narrowly facilitating coordination might produce novel collusion with substantial negative externalities on outsiders. But then ex hypothesi those outsiders have an outsized incentive to block that collusion, if only they can foresee it and coordinate in turn.

It's confusing.