Lizka

Bio

I'm a researcher at Forethought; before that, I ran the non-engineering side of the EA Forum (this platform), ran the EA Newsletter, and worked on some other content-related tasks at CEA. [More about the Forum/CEA Online job.]

Selected posts

- Disentangling "Improving Institutional Decision-Making"

- [Book rec] The War with the Newts as “EA fiction”

- EA should taboo "EA should"

- Invisible impact loss (and why we can be too error-averse)

- Celebrating Benjamin Lay (died on this day 265 years ago)

- Remembering Joseph Rotblat (born on this day in 1908)

Background

I finished my undergraduate studies with a double major in mathematics and comparative literature in 2021. I was a research fellow at Rethink Priorities in the summer of 2021 and was then hired by the Events Team at CEA. I later switched to the Online Team. In the past, I've also done some (math) research and worked at Canada/USA Mathcamp.

Posts 172

Comments574

Topic contributions267

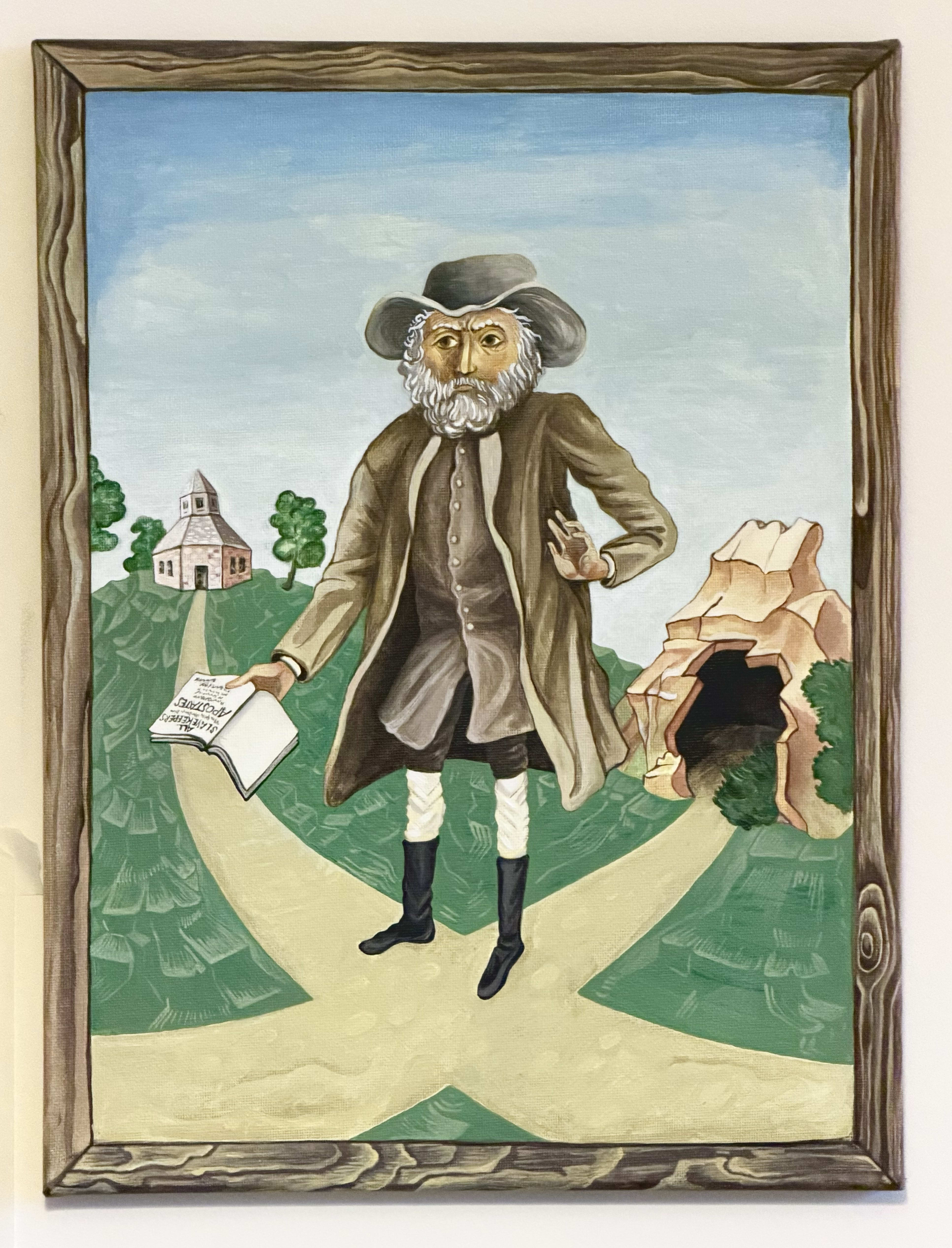

I didn't end up writing a reflection in the comments as I'd meant to when I posted this, but I did end up making two small paintings inspired by Benjamin Lay & his work. I've now shared them here.

I think of today (February 8) as "Benjamin Lay Day", for what it's worth. (Funny timing :) .)

Another one I'd personally add might be November 4 for Joseph Rotblat. And just in case you haven't seen / just for reference, there are some related resources on the Forum, e.g. here https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/events-on-the-ea-forum, and here https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/QFfWmPPEKXrh6gZa3/the-ea-holiday-calendar .

In fact I think the Forum team may also still maintain a list/calendar of possible days to celebrate somewhere. ( @Dane Valerie might know?)

Benjamin Lay — "Quaker Comet", early (radical) abolitionist, general "moral weirdo" — died on this day 267 years ago.

I shared a post about him a little while back, and still think of February 8 as "Benjamin Lay Day".

...

Around the same time I also made two paintings inspired by his life/work, which I figured I'd share now. One is an icon-style-inspired image based on a portrait of him[1]:

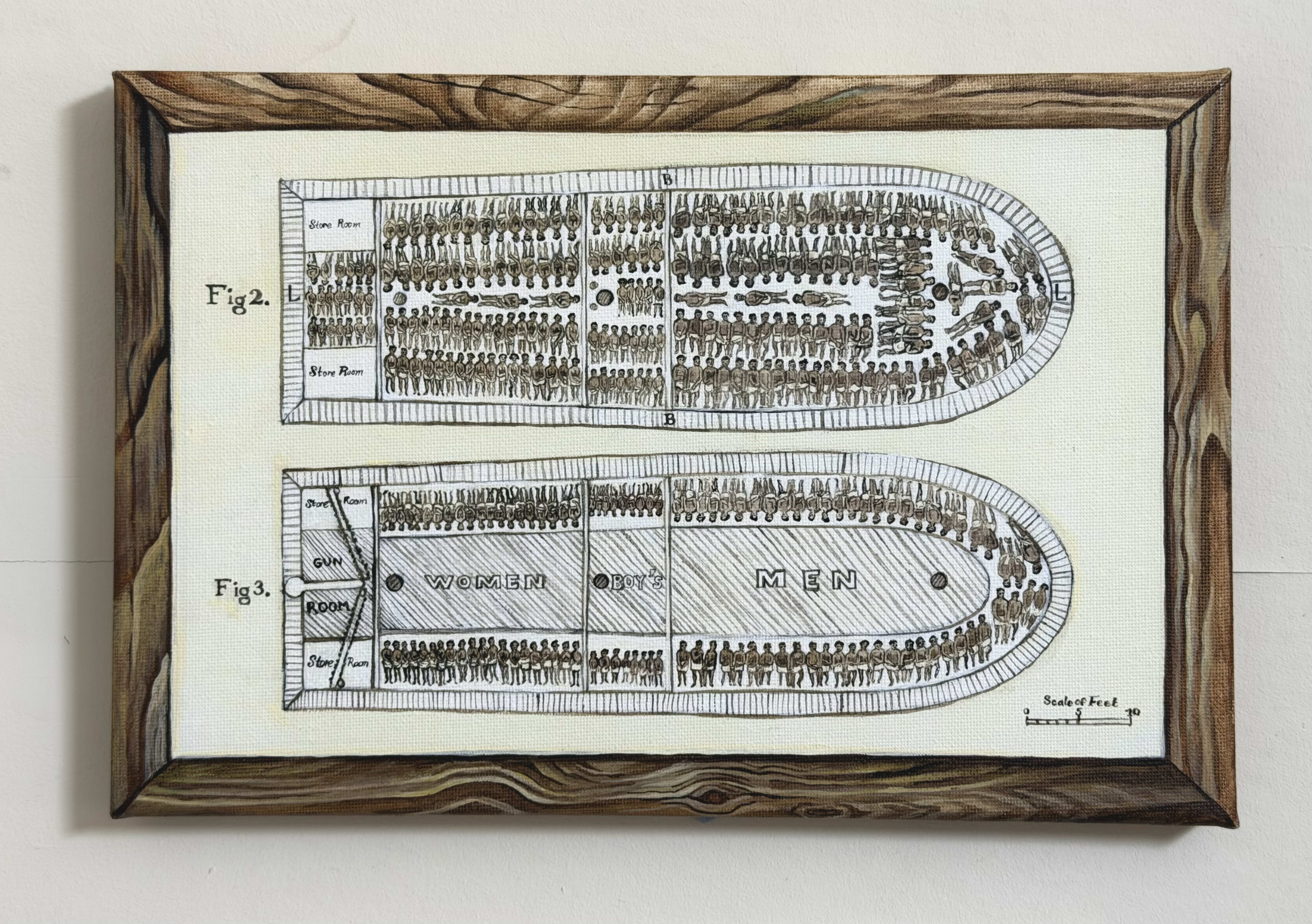

The second is based on a print depicting the floor plan of an infamous slave ship (Brooks). The print was used by abolitionists (mainly(?) the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade) to help communicate the horror of the trade.

I found it useful to paint it (and appreciate having it around today). But I imagine that not everyone might want to see it, so I'll skip a few lines here in case you expanded this quick take and decide you want to scroll past/collapse it instead.

.

.

.

When thinking about the impacts of AI, I’ve found it useful to distinguish between different reasons for why automation in some area might be slow. In brief:

- raw performance issues

- trust bottlenecks

- intrinsic premiums for “the human factor”

- adoption lag

- motivated/active protectionism towards humans

I’m posting this mainly because I’ve wanted to link to this a few times now when discussing questions like "how should we update on the shape of AI diffusion based on...?". Not sure how helpful it will be on its own!

In a bit more detail:

(1) Raw performance issues

There’s a task that I want an AI system to do. An AI system might be able to do it in the future, but the ones we have today just can’t do it.

For instance:

- AI systems still struggle to stay coherent over long contexts, so it’s often hard to use an AI system to build out a massive codebase without human help, or write a very consistent detective novel.

- Or I want an employee who’s more independent; we can get aligned on some goals and they will push them forward, coming up with novel pathways, etc.

- (Other capability gaps: creativity/novelty, need for complicated physical labor, …)

- [Edit: this UK AISI paper on limitations of current AI looks good]

A subclass here might be performance issues that are downstream of “interface mismatch”.[1] Cases where AI might be good enough at some fundamental task that we’re thinking of (e.g. summarizing content, or similar), but where the systems that surround that task or the interface through which we’re running the thing — which are trivial for humans — is a very poor fit for existing AI, and AI systems struggle to get around that.[2] (E.g. if the core concept is presented via a diagram, or requires computer use stuff.) In some other cases, we might separately consider whether the AI systems has the right affordances at all.

This is what we often think about when we think about the AI tech tree / AI capabilities. Others are often important, though:

(2) Verification & trust bottlenecks

The AI system might be able to do the task, but I can't easily check its work and prefer to just do it myself or rely on someone I trust. Or I can't be confident the AI won't fail spectacularly in some rare but important edge cases (in ways a human almost certainly wouldn't).[3]

For instance, maybe I want someone to pull out the most surprising and important bits from some data, and I can’t trust the judgement of an AI system the way I can trust someone I’ve worked with. Or I don’t want to use a chatbot in customer-facing stuff in case someone finds a way to make it go haywire.

A subclass here is when one can’t trust AI providers (and open-source/on-device models aren’t good enough) for some use case. Accountability sinks also play a role on the “trust” front. Using AI for some task might complicate the question of who bears responsibility when things go wrong, which might matter if accountability is load-bearing for that system. In this case we might go for assigning a human overseer.[4]

(3) Intrinsic premiums for “the human factor”[5]

The task *requires* human involvement, or I intrinsically prefer it for some reason.

E.g. AI therapists are less effective because knowing that the person on the other end is a person is actually useful to get me to do my exercises. Or: I might pay more to see a performance by Yo Yo Ma than by a robot because that’s my true preference; I get less value from a robot performance.

A subclass here is cases where the value I’m getting is testimony — e.g. if I want to gather user data or understand someone’s internal experience — that only humans can provide (even if AI can superficially simulate it).

(4) Adoption lag & institutional inertia

AI systems can do this, people would generally prefer that, there aren’t legal or similar “hard barriers” to AI use, etc., but in practice this is being done by humans.

E.g. maybe AI-powered medical research isn’t happening because the people/institutions who could be setting this kind of automation up just haven’t gotten to it yet.

Adoption lags might be caused by stuff like: sheer laziness, coordination costs, lack of awareness/expertise, attention scarcity — the humans currently involved in this process don’t have enough slack — or similar, active (but potentially hidden) incumbent resistance, or maybe bureaucratic dysfunction (no one has the right affordances).

(My piece on the adoption gap between the US government and ~industry is largely about this.)

(5) Motivated/active protectionism towards humans

AI systems that can do this, there’s no intrinsic need for human involvement, nor real capabilities/trust bottlenecks getting in the way. But we’ll deliberately continue relying on human labor for ~political reasons — not just because we’re moving slowly.

E.g. maybe we’ve hard-coded a requirement that a human lawyer or teacher or driver (etc.) is involved. A particularly salient subclass/set of examples here is when a group of humans has successfully lobbied a government to require human labor (where it might be blatantly obvious that it’s not needed). In other cases, the law (or anatomy of an institution) might incidentally require humans in the loop via some other requirement.

This is a low-res breakdown that might be missing stuff. And the lines between these categories can be very fuzzy. For instance, verification difficulties (2) can provide justification for protectionism (5) or further slow down adoption (4).

But I still think it’s useful to pay attention to what’s really at play, and worry we too often think exclusively in terms of raw performance issues (1) with a bit of diffusion lag (4).

- ^

Note OTOH that sometimes the AI capabilities are already there, but bad UI or lack of some complementary tech is still making those capabilities unusable.

- ^

I’m listing this as a “raw performance issue” because the AI systems/tools will probably keep improving to better deal with such clashes. But I also expect the surrounding interfaces/systems to change as people try to get more value from available AI capabilities. (E.g. stuff like robots.txt.)

- ^

Sometimes the edge cases are the whole point. See also: Heuristics That Almost Always Work - by Scott Alexander

- ^

Although I guess then we should be careful about alert fatigue/false security issues. IIRC this episode discusses related stuff: Machine learning meets malware, with Caleb Fenton (search for “alert fatigue” / “hypnosis”)

- ^

(There's also the opposite; cases where we'd actively prefer humans not be involved. For instance, all else equal, I might want to keep some information private — not want to share it with another person — even if I'd happily share with an AI system.)

Yeah, I guess I don't want to say that it'd be better if the team had people who are (already) strongly attached to various specific perspectives (like the "AI as a normal technology" worldview --- maybe especially that one?[1]). And I agree that having shared foundations is useful / constantly relitigating foundational issues would be frustrating. I also really do think the points I listed under "who I think would be a good fit" — willingness to try on and ditch conceptual models, high openness without losing track of taste, & flexibility — matter, and probably clash somewhat with central examples of "person attached to a specific perspective."

= rambly comment, written quickly, sorry! =

But in my opinion we should not just all (always) be going off of some central AI-safety-style worldviews. And I think that some of the divergence I would like to see more of could go pretty deep - e.g. possibly somewhere in the grey area between what you listed as "basic prerequisites" and "particular topics like AI timelines...". (As one example, I think accepting terminology or the way people in this space normally talk about stuff like "alignment" or "an AI" might basically bake in a bunch of assumptions that I would like Forethought's work to not always rely on.)

One way to get closer to that might be to just defer less or more carefully, maybe. And another is to have a team that includes people who better understand rarer-in-this-space perspectives, which diverge earlier on (or people who are by default inclined to thinking about this stuff in ways that are different from others' defaults), as this could help us start noticing assumptions we didn't even realize we were making, translate between frames, etc.

So maybe my view is that (1) there were more ~independent worldview formation/ exploration going on, and that (2) the (soft) deferral that is happening (because some deferral feels basically inevitable) were less overlapping.

(I expect we don't really disagree, but still hope this helps to clarify things. And also, people at Forethought might still disagree with me.)

- ^

In particular:

If this perspective involves a strong belief that AI will not change the world much, then IMO that's just one of the (few?) things that are ~fully out of scope for Forethought. I.e. my guess is that projects with that as a foundational assumption wouldn't really make much sense to do here. (Although IMO even if, say, I believed that this conclusion was likely right, I might nevertheless be a good fit for Forethought if I were willing to view my work as a bet on the worlds in which AI is transformative.)

But I don't really remember what the "AI as normal.." position is, and could imagine that it's somewhat different — e.g. more in the direction of "automation is the wrong frame for understanding the most likely scenarios" / something like this. In that case my take would be that someone exploring this at Forethought could make sense (haven't thought about this one much), and generally being willing to consider this perspective at least seems good, but I'd still be less excited about people who'd come with the explicit goal of pursuing that worldview & no intention of updating or whatever.

--

(Obviously if the "AI will not be a big deal" view is correct, I'd want us to be able to come to that conclusion -- and change Forethught's mission or something. So I wouldn't e.g. avoid interacting with this view or its proponents, and agree that e.g. inviting people with this POV as visitors could be great.)

ore Quick sketch of what I mean (and again I think others at Forethought may disagree with me):

- I think most of the work that gets done at Forethought builds primarily on top of conceptual models that are at least in significant part ~deferring to a fairly narrow cluster of AI worldviews/paradigms (maybe roughly in the direction of what Joe Carlsmith/Buck/Ryan have written about)

- (To be clear, I think this probably doesn't cover everyone, and even when it does, there's also work that does this more/less, and some explicit poking at these worldviews, etc.)

- So in general I think I'd prefer the AI worldviews/deferral to be less ~correlated. On the deferral point — I'm a bit worried that the resulting aggregate models don't hold together well sometimes, e.g. because it's hard to realize you're not actually on board with some further-in-the-background assumptions being made for the conceptual models you want to pull in.

- And I'd also just like to see more work based on other worldviews, even just ones that complicate the paradigmatic scenarios / try to unpack the abstractions to see if some of the stuff that's been simplified away is blinding us to important complications (or possibilities).[1]

- I think people at Forethought often have some underlying ~welfarist frames & intuitions — and maybe more generally a tendency to model a bunch of things via something like utility functions — as opposed to thinking via frames more towards the virtue/rights/ethical-relationships/patterns/... direction (or in terms of e.g. complex systems)

- We're not doing e.g. formal empirical experiments, I think (although that could also be fine given this area of work, just listing as it pops into my head)

- There's some fuzzy pattern in the core ways in which most(?) people at Forethought seem to naturally think, or in how they prefer to have research discussions, IMO? I notice that the types of conversations (and collaborations) I have with some other people go fairly differently, and this leads me to different places.

- To roughly gesture at this, in my experience Forethought tends broadly more towards a mode like "read/think -> write a reasonably coherent doc -> get comments from various people -> write new docs / sometimes discuss in Slack or at whiteboards (but often with a particular topic in mind...)", I think? (Vs things like trying to map more stuff out/think through really fuzzy thoughts in active collaboration, having some long topical-but-not-too-structured conversations that end up somewhere unexpected, "let's try to make a bunch of predictions in a row to rapidly iterate on our models," etc.)

- (But this probably varies a decent amount between people, and might be context-dependent, etc.)

- IIRC many people have more expertise on stuff like analytic philosophy, maybe something like econ-style modeling, and the EA flavor of generalist research than e.g. ML/physics/cognitive science/whatever, or maybe hands-on policy/industry/tech work, or e.g. history/culture... And there are various similarities in people's cultural/social backgrounds. (I don't actually remember everyone's backgrounds, though, and think it's easy to overindex on this / weigh it too heavily. But I'd be surprised if that doesn't affect things somewhat.)

I also want to caveat that:

- (i) I'm not trying to be exhaustive here, just listing what's salient, and

- (ii) in general it'll be harder for me to name things that also strongly describe me (although I'm trying, to some degree), especially as I'm just quickly listing stuff and not thinking too hard.

(And thanks for the nice meta note!)

- ^

I've been struggling to articulate this well, but I've recently been feeling like, for instance, proposals on making deals with "early [potential] schemers" implicitly(?) rely on a bunch of assumptions about the anatomy of AI entities we'd get at relevant stages.

More generally I've been feeling pretty iffy about using game-theoretic reasoning about "AIs" (as in "they'll be incentivized to..." or similar) because I sort of expect it to fail in ways that are somewhat similar to what one gets if one tries to do this with states or large bureaucracies or something -- iirc the fourth paper here discussed this kind of thing, although in general there's a lot of content on this. Similar stuff on e.g. reasoning about the "goals" etc. of AI entities at different points in time without clarifying a bunch of background assumptions (related, iirc).

Ah, @Gregory Lewis🔸 says some of the above better. Quoting his comment:

- [...]

- So ~everything is ultimately an S-curve. Yet although 'this trend will start capping out somewhere' is a very safe bet, 'calling the inflection point' before you've passed it is known to be extremely hard. Sigmoid curves in their early days are essentially indistinguishable from exponential ones, and the extra parameter which ~guarantees they can better (over?)fit the points on the graph than a simple exponential give very unstable estimates of the putative ceiling the trend will 'cap out' at. (cf. 1, 2.)

- Many important things turn on (e.g.) 'scaling is hitting the wall ~now' vs. 'scaling will hit the wall roughly at the point of the first dyson sphere data center' As the universe is a small place on a log scale, this range is easily spanned by different analysis choices on how you project forward.

- Without strong priors on 'inflecting soon' vs. 'inflecting late', forecasts tend to be volatile: is this small blip above or below trend really a blip, or a sign we're entering a faster/slow regime?

- [...]

I tried to clarify things a bit in this reply to titotal: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/iJSYZJJrLMigJsBeK/lizka-s-shortform?commentId=uewYatQz4dxJPXPiv

In particular, I'm not trying to make a strong claim about exponentials specifically, or that things will line up perfectly, etc.

(Fwiw, though, it does seem possible that if we zoom out, recent/near-term population growth slow-downs might be functionally a ~blip if humanity or something like it leaves the Earth. Although at some point you'd still hit physical limits.)

Oh, apologies: I'm not actually trying to claim that things will be <<exactly.. exponential>>. We should expect some amount of ~variation in progress/growth (these are rough models, we shouldn't be too confident about how things will go, etc.), what's actually going on is (probably a lot) more complicated than a simple/neat progression of new s-curves, etc.

The thing I'm trying to say is more like:

- When we've observed some datapoints about a thing we care about, and they seem to fit some overall curve (e.g. exponential growth) reasonably well,

- then pointing to specific drivers that we think are responsible for the changes — & focusing on how those drivers might progress or be fundamentally limited, etc. — often makes us (significantly) overestimate bottlenecks/obstacles standing in the way of progress on the thing that we actually care about.

- And placing some weight on the prediction that the curve will simply continue[1] seems like a useful heuristic / counterbalance (and has performed well).

(Apologies if what I'd written earlier was unclear about what I believe — I'm not sure if we still notably disagree given the clarification?)

A different way to think about this might be something like:

- The drivers that we can point to are generally only part of the picture, and they're often downstream of some fuzzier higher-level/"meta" force (or a portfolio of forces) like "incentives+..."

- It's usually quite hard to draw a boundary around literally everything that's causing some growth/progress

- It's also often hard to imagine, from a given point in time, very different ways of driving the thing forward

- (e.g. because we've yet to discover other ways of making progress, because proxies we're looking at locally implicitly bake in some unnecessary assumptions about how progress on the thing we care about will get made, etc.)

- So our stories about what's causing some development that we're observing are often missing important stuff, and sometimes we should trust the extrapolation more than the stories / assume the stories are incomplete

Something like this seems to help explain why views like "the curve we're observing will (basically) just continue" have seemed surprisingly successful, even when the people holding those "curve go up" views justified their conclusions via apparently incorrect reasoning about the specific drivers of progress. (And so IMO people should place non-trivial weight on stuff like "rough, somewhat naive-seeming extrapolation of the general trends we're observing[2]."[3])

[See also a classic post on the general topic, and some related discussion here, IIRC: https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/aNAFrGbzXddQBMDqh/moore-s-law-ai-and-the-pace-of-progress ]

- ^

Caveat: I'd add "...on a big range/ the scale we care about"; at some point, ~any progress would start hitting ~physical limits. But if that point is after the curve reshapes ~everything we care about, then I'm basically ignoring that consideration for now.

- ^

Obviously there are caveats. E.g.:

- the metrics we use for such observations can lead us astray in some situations (in particular they might not ~linearly relate to "the true thing we care about")

- we often have limited data, we shouldn't be confident that we're predicting/measuring the right thing, things can in fact change over time and we should also not forget that, etc.

(I think there were nice notes on this here, although I've only skimmed and didn't re-read https://arxiv.org/pdf/2205.15011 )

- ^

Also, sometimes we do know what

I'm also worried about an "epistemics" transformation going poorly, and agree that how it goes isn't just a question of getting the right ~"application shape" — something like differential access/adoption[1] matters here, too.

@Owen Cotton-Barratt, @Oliver Sourbut, @rosehadshar and I have been thinking a bit about these kinds of questions, but not as much as I'd like (there's just not enough time). So I'd love to see more serious work on things like "what might it look for our society to end up with much better/worse epistemic infrastructure (and how might we get there)?" and "how can we make sure AI doesn't end up massively harming our collective ability to make sense of the world & coordinate (or empower bad actors in various ways, etc.).

This comment thread on an older post touched on some related topics, IIRC