April 2025

By: Gabriela Pardo Mendoza

This project was conducted as part of the "Careers with Impact" program during the 14-week mentoring phase. You can find more information about the program in this post.

2. Contextualization of the problem

This year, the World Economic Forum (2025) issued a stark warning: disinformation could become the biggest global threat by 2027. In a context of hypercommunication, the misuse of synthetic media such as deepfake could become an instrument with the potential to amplificate this risk and, consequently, generate massive manipulation, damage to democracies and institutions, cyberattacks and increased political tensions. In the face of this situation, high-level international organizations -such as UNESCO, OECD (2024), EUROPOL (2024), INTERPOL (2024) and the FBI (2021; 2023), to mention a few- have raised warnings about the malicious use of this technology and its remarkable increase in recent years.

By 2020, more than 100 million deepfake videos were posted online and reached around 5.4 billion views on YouTube (Sentinel, 2020, cited in Whittaker et al., 2023). Such has been its increase that, last year, an article in Forbes magazine named 2024 as "the year of deepfake". In the face of its malicious use, it reflects an alarming situation that current AI regulatory frameworks. The speed with which this technology evolves exceeds the response capacity of many legal systems, because so far, there are no robust legal frameworks that address this issue. This leaves open loopholes that can be exploited to amplificar misinformation, manipulation and other problems that destabilize society.

The objective of this project is to identificate the existing gaps in the legal frameworks that govern the governance of the IA, particularly with regard to preventing and mitigating the malicious use of deepfakes. Addressing this challenge not only makes visible emerging and high-impact problem, but also helps lay a foundation to strengthen AI governance to act on a layer of preventing catastrophic events, information integrity and global security in the years to come.

3. Research Question.

What legal frameworks have been implemented by leading countries in Artificial Intelligence to address the malicious use of deepfakes?

4. Objectives

4.1. General

● Identifify existing gaps in AI governance frameworks around the prevention and mitigation of malicious use of deepfakes.

4.2. Particular (Specific) Objectives

● Identificate keyword definitions from deepfake.

● Generate a database of AI governance documents from leading AI countries.

● Identificate keyword definitions from deepfake.

within selected governance documents

4.3 Personal Objectives

● Boost my mixed research skills and analytical abilities. ● Familiarize myself with the AI governance environment, which is targeted as an elemental area for the safe, fiable and ethical development of this technology.

● Explore information on deepfakes, as they represent a new challenge for computer security and anthropological analysis.

● Intruding into the social impact of AI vs. risky technologies.

5. Methodology

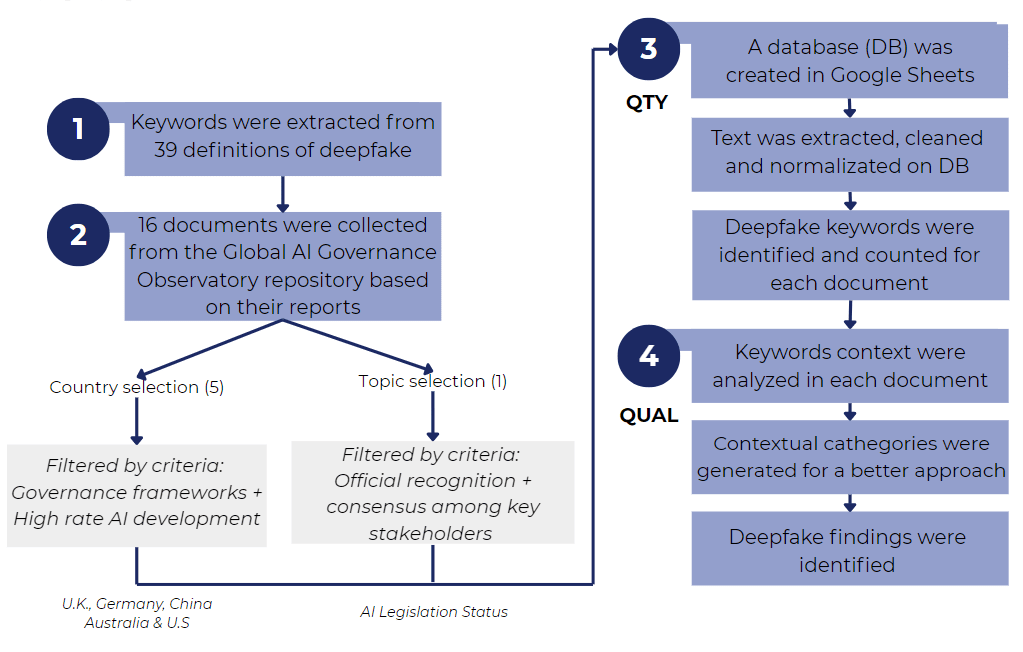

A Google Sheets document was generated for the creation of a database (DB) that stores specific information to carry out an in-depth analysis of these documents with the support of mixed methods (Figure 1). The database of this project can be consulted through the following link.

a) Identification of deepfake keywords.

Thirty-nine deepfake definitions were collected from international organizations, digital repositories, NGOs and governmental entities, which were stored in a separate book within the database. Through manual authentication in Google Colab and the use of the Python gspread library, this data was accessed to extract the most frequent words. The final code was stored on GitHub (To consult the code, it can be done through the following link).

b) Documentary selection

Sixteen governance documents were analyzed: eleven in English, three in German and two in Chinese. For this purpose, the Global AI Governance Observatory repository was consulted to select countries and key topics around governance of artificial intelligence, taking as reference the Global Index for AI Safety (GIAIS) (2025) and the AI Governance International Evaluation Index (AGILE Index) (2024). It is recognized that the structure of such repository may present limitations or biases, so it is possible that there are legal frameworks or relevant documents that have not been included in this analysis. Likewise, the challenges presented by the cultural and syntactical language barriers when analyzing documents not available in English are recognized. This is seen as a necessity for a more thorough examination of governance documents in other languages. It is also assumed that the present project may have its own limitations, inherent to a first approach to these issues, which opens the door to future research to deepen and complement this work. The selection was based on:

● Topics

The third pillar (Instruments for AI governance) of the AGILE Index Report (2024) was selected. It is important to note that the pillars described in this document constitute a useful interpretative architecture, but are not without potential limitations. this category, which is divided into seven topics, AI Legislation Status was chosen. This selection responds to the fact that the documents in this topic are oficially recognized by governments, and their formulation is the result of consensus among key actors, including experts, academics and scientists, which reinforces their legitimacy as a frame of reference in AI regulation.

● Countries

The selection was based on two criteria. First, countries with national security laws and technical or policy frameworks in place in IA for the current year, according to GIAIS (2025), were identified: Australia, China, Germany, Japan, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, totaling eight. Secondly, from this list, the five countries with the best rating in the level of technology development, according to the AGILE Index, were chosen. These countries are the United States 99.8), the United Kingdom (69.90), China (64.7), Germany (59.80) and Australia (59.1).

It has been observed that, as a country advances AI development, its capacity to generate governance instruments in this area also increases. A key factor in the selection of the countries analyzed is that the regulatory frameworks of the nations with the highest level of AI development-mainly located in the global north can have a significant impact on developing countries in the global south. This influence translates into opportunities for knowledge transfer and international cooperation, essential to mitigate the risks associated with the malicious use of technologies such as deepfake in particularly vulnerable regions marked by inequality, lack of access to information, lack of infrastructure, corruption, abuse of power, and human rights violations.

In summary, sound regulatory frameworks generated in the global north have the potential to drive policy formulation and the active participation of actors in the global south. This would make it possible to address the challenges of deepfake from a contextualized perspective, considering the material, technological, social and cultural realities of each region.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria:

Documents available in the Global Observatory of AI Governance data source and those included in Appendix C (List of National AI Safety Governance Instruments) of the AGILE Index (2025) were selected for the selected countries. Documents whose website was not available, whose location on the platform was unclear, or which were not in text formats such as HTML or PDF were excluded.

April 2025

c) Automated textual analysis (quantitative)

An automated process was developed in Python to extract and parse text from the Google Sheets database using gspread authentication. Natural language (NLP) techniques were applied with the Natural Language Toolkit (nltk) library to normalize the data (lowercase conversion, punctuation removal and stopword filtering) in English, German and Chinese. Keywords related to deepfakes - including their translation into German and Chinese - were identified within the text, recording their frequency and distribution. The final code was run with Google Colab, and stored in a GitHub repository to ensure reproducibility and scalability (To consult the code, it can be done through the following link).

d) Manual text analysis (qualitative)

The texts of the governance documents were imported into the web version of the ATLAS.ti software. The context of the sentences in which the units of analysis (keywords) identified by the automated analysis figurated was examined determine whether these mentions, including those at a high level, were related to the deepfakes phenomenon. From this review, instances where there was no relevant connection to this technology were discarded.

Figure 1. Methodology used in the project. This was divided into four stages, with two main nuances: document selection and textual analysis. 39 deepfake definitions were compiled to extract the keywords, as a starting point. Subsequently, five countries with regulatory frameworks and high AI development index were selected, according to the GIAIS (2025) and AGILE (2024) indexes. During the second stage; selected documents were collected and processed to extract and analyze their artificial content and manually, to identificate keywords related to deepfakes.

6. Results and Discussion

1) Quantitative Analysis

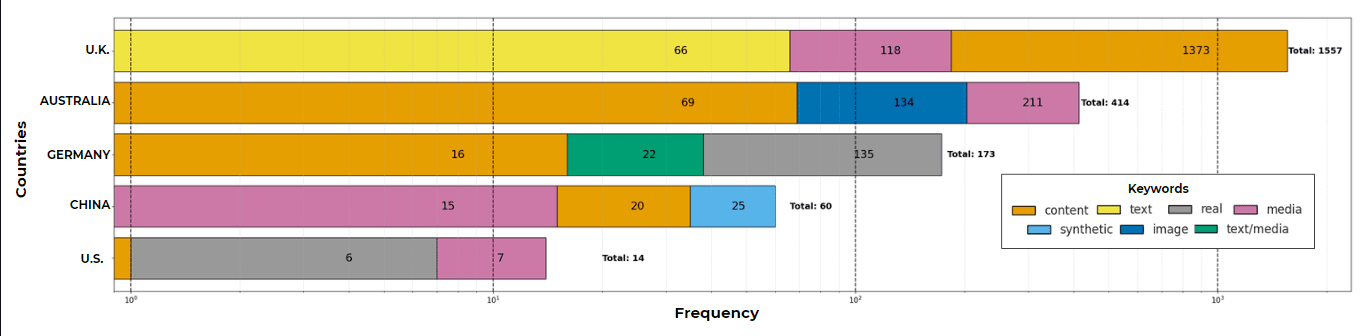

From the analysis of 39 deepfake definitions, 20 keywords were identified that reveal the core elements of this technology. Among the most prominent figures are "audio," "video," "media," "created," "content," "synthetic," "real," "manipulated," "realistic," "fake," "never," "image," "someone," "voice," "saying," "something," and "face." Many of these words coincide with the terms identified by Whittaker and collaborators (2023) such as "videos," "audio," "realistic," "fake," "artificial," "learning," "media," and "saying" as key components in the construction of definitions about deepfakes. Within the texts, the term "content" is the most recurrent term with 1,479 mentions in total, of which, 1,373 come from UK documents. Other predominant terms vary by country: "media" leads in Australian and US texts; "real" in German texts; and "synthetic" in Chinese texts (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stacked column chart of the most repeated words within the governance documents, organized by country. This shows the three words with the highest frequency within the legal corpus.

A notable difference was also identified in the number of words found in the U.S. documents compared to the rest of the countries analyzed. This gap is attributed to the deactivation or removal of several links from the Observatory's repository, possibly as a result of a shift in the political agenda following the presidential inauguration of Donald Trump on January 20. It should be noted that the president has been indirectly linked to incidents with deepfakes, such as the dissemination of AI-generated images falsely depicting singer Taylor Swift giving her political support (AIID, 2024).

In the cases of Australia, Germany and the United Kingdom, many of the most frequent words identified in their documents -such as media, content or real- correspond to an abstract level, which means that they can be found in multiple contexts without necessarily alluding to deepfakes. Therefore, their presence does not imply a direct thematic focus on this technology. However, it is worth noting that one of the UK documents is the only one in the entire sample with the only mention of the word "deepfake."

The most significant quantitative finding is found in the case of China, where the words "synthetic", "content" and "media" top the list of most frequent terms. Unlike in other countries, the terms contained in the documents from the big Asian country show a close relationship with deepfakes, which suggested a more explicit and consistent approach to this technology.

2) Qualitative analysis

Through an inductive reading, various thematic approaches were identified in the documents, linked to the keywords detected in the quantitative analysis. This made it possible to establish six general categories that structure the content of the texts: 1) Generative Artificial Intelligence, 2) Processing of personal information, 3) Online security environment, 4) Disinformation, 5) Gender-based attacks and 6) Fraud or scam. Only the first one has a direct and consistent relationship with deepfakes; however, the others reflect legislative concerns that, while do not explicitly allude to this technology, they do connect to its possible malicious uses as reported by AIID and OECD (2024; 2025). . Although we know that all the analyzed documents are valuable in their own contexts, the findings of the analysis suggested that out of the sixteen documents, only three address the issue of the malicious use of deepfakes. Although we know that all the analyzed documents contain keywords linked to deepfakes, the findings of the analysis suggested that out of the sixteen documents, only three from two countries —the United Kingdom and China— directly address the issue of the malicious use of deepfakes (Table 1).

For the case of the United Kingdom, the problem of deepfakes is explicitly addressed within its legal framework in relation to the creation of deepfake pornography. This corresponds with the description made by Montasari (2024), who highlights that recent initiatives in the United Kingdom focus on the generation of non-consensual synthetic pornography. This country's legal framework incorporates a definition of "image" that includes digitally manipulated material, and in their Non Statutory AI Regulation Principles they directly mention deepfakes in this context-the only explicit reference to this technology in entire corpus analyzed-which represents a major step forward in the fight against digital gender-based violence. In contrast, , there is an absence of any discussion of other issues associated with the malicious use of deepfakes in other spaces that have the potential to pose risks, such as political manipulation and disinformation.

| Country | Document | Categories present | Deepfake? |

China

| Interim Measures for the Management of Generative AI Services | Generative Artificial Intelligence, Online security, Processing of personal information, Disinformation, Gender based attacks, Fraud or scam. | ✔ |

| Internet Information Service Deep Synthesis Management Provisions |

Generative Artificial Intelligence, Processing of personal information, Disinformation, Gender based attacks

| ✔ | |

| Provisions on the Management of Algorithmic Recommendations in Internet Information Services |

Processing of personal information, Disinformation

| ✗ | |

| The Cybersecurity Law | Online security, Fraud or scam | ✗ | |

| Personal Information Protection Law | Processing of personal information | ✗ | |

UK.

| Non-Statutory AI Regulation Principles | Generative Artificial Intelligence, Online security, Gender based attacks

| ✔ |

| Draft Online Safety Bill 2023 | Processing of personal information,Online Security, Disinformation, Gender based attacks, Fraud or scam | ✗ | |

| Data protection Act | Processing of personal information | ✗ | |

Germany

| Federal Data Protection Act | Processing of personal information | ✗ |

| White Paper on AI (EU) | Processing of personal information | ✗ | |

| Second law on strengthening the security of information technology systems | - | ✗ | |

| Consumer Protection Act | - | ✗ | |

| Australia | Online Safety Act | Online security, Gender based attacks | ✗ |

US

| The Federal Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Act 2023

| — | ✗ |

| Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2022 | — | ✗ | |

| S.754 | — | ✗ | |

Table 1. Exploratory findings of keyword contexts in the selected governance documents. These were organized in such a way that the findings from each of the documents could be visualized, and whether these have any relationship to deepfakes. | |||

Finally, China is positioned at the forefront among the analyzed countries in terms of governance of Generative Artificial Intelligence and deep synthesis. These results are in agreement with Montasari (2024); so we suggest that the Asian great is positioned -so far- as the country with the most robust preventive measures to deal with deepfakes. Among these measures is the obligation to label AI-generated content, with the finds of preventing disinformation and eliminating material potentially harmful to the public interest or national security. In addition, its legal framework explicitly addresses the digital manipulation of voice, face and body posture through deep synthesis. This ranges from the generation and editing of text and voice, to the creation, replacement or modification of human faces in images and videos.

The review of Chinese documents made by other authors, such as Zheng and his collaborators (2025), show that the political-legal agenda of this country is not only limited to technical regulation, but also advocates digital literacy and cybersecurity education for users, together forming a series of measures to prevent deepfakes from unleashing events that violate legal standards or compromise social stability (Zheng et al., 2025, p. 15). An important aspect is that, globally, research on deepfakes is concentrated in Chinese institutions (Sandoval et al., 2024, p. 9), which shows the attention they pay to the problem. It also highlights the fact that the Asian giant incorporates the concept of "immersive virtual reality scenarios", referring to highly realistic and interactive environments created with deep synthesis technologies, which demonstrates a comprehensive view of the potential impact of these tools in the digital sphere and the real world.

7. Perspectives

Based on the results of this project, it is clear that there is still a long way to go to establish good AI governance. That frames emerging challenges and evolves in step with technologies such as deepfakes, while remaining responsive to the diverse social and cultural needs of a globalized world.

As another possible approach to the analysis of the status of AI governance around deepfakes, it would be pertinent to conduct complementary analyses of existing legal frameworks from a different selection of countries or categories, as well as to identify other approaches based on other pillars for governance and topics that transcend legal instruments. At the same time, new sources and documentary repositories could be explored to provide a broader vision of AI governance efforts.

In addition, among the main challenges in the short term is the need to standardize both the definition of deepfake itself and the criteria for counting the incidents associated with this technology, in order to design more effective governance strategies. It is equally important to recognize that the logic of deepfake production does not constitute a completely new phenomenon, but has been amplified by its insertion in specific contexts, moments and material conditions. This implies understanding deepfakes as part of a social and cultural phenomenon, whose consumption occurs in particular cultural frameworks that must be analyzed on their own terms. This perspective underscores the need to promote holistic and multidisciplinary studies in the field of AI, as well as to maintain a constant effort to strengthen the information literacy of audiences.

8. References

AIID (2024). List of incidents. Artificial Intelligence Indicent Database. https://incidentdatabase.ai/es/.

Europol Innovation Lab (2024). Facing reality? Law enforcement and the challenge of deepfakes: An observatory report from the Europol innovation lab. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2813/158794

Global AI Governance Observatory (2025). Global Index for AI Safety. AGILE Index on Global AI Safety Readiness. https://www.agile index.ai/Global-Index-For-AI-Safety-Report-EN. pdf

Homeland Security & Federal Bureau of Investigation (2021). Increasing Threat of Deepfake Identities. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/increasing_th reats_of_deepfake_identities_0.pdf

Montasari, R. (2024). Responding to Deepfake Challenges in the United Kingdom: Legal and Technical Insights with Recommendations. In R. Montasari, Cyberspace, Cyberterrorism and the International Security in the Fourth Industrial Revolution pp. 241-258). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50454-9_12

National Security Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, & Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (2023). Contextualizing Deepfake Threats to Organizations. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Sep/12/2003298925/-1/-1/0/CSI-DEEPFAKE-THREATS.PDF

OECD (2024). Facts versus falsehoods: Strengthening democracy through information integrity. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/06f8ca41-es

OECD. (2025). AI incidents monitor. OECD.AI. https://oecd.ai/en/incidents?search_terms=%5B%5D&and_conditi on=false&from_date=2014-01-01&to_date=2025-04-18&properties_ config=%7B%22principles%22:%5B%5D,%22industries%22:%5B%5 D,%22harm_types%22:%5B%5D,%22harm_levels%22:%5B%5D,%22 harmed_entities%22:%5B%5D%7D&only_threats=false&order_by= date&num_results=20

Sandoval, M.-P., de Almeida Vau, M., Solaas, J., & Rodrigues, L. (2024). Threat of deepfakes to the criminal justice system: A systematic review. Crime Science, 13(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00239-1

The International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL). (2024). Beyond Illusions. Unmasking the threat of synthetic media for law enforcement Report 2024.

UNESCO, Rumman Chowdhorry, & Dhanya Lakshmi (2023). "Your opinion doesn't matter, anyway". Exposing Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence in an Era of Generative AI.

Whittaker, L., Mulcahy, R., Letheren, K., Kietzmann, J., & Russell-Bennett, R. (2023). Mapping the deepfake landscape for innovation: A multidisciplinary systematic review and future research agenda. Technovation, 125, 102784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102784

World Economic Forum (2025). Global Risks Report 2025. https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_202 5.pdf

Yi Zeng, Enmeng Lu, Xin Guan, Cunqing Huangfu, Zizhe Ruan, & Ammar Younas (2024). AI Governance InternationaL Evaluation Index (AGILE Index). Center for Long-term Artificial Intelligence (CLAI), International Research Center for AI Ethics and Governance, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences. https://agile-index.ai/.

Zheng, G., Shu, J., & Li, K. (2025). Regulating deepfakes between Lex Lata and Lex ferenda-A comparative analysis of regulatory approaches in the U.S., the EU and China. Crime, Law and Social Change, 83(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-024-10197-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-024-10197-z

● Personal Reflexion.

Careers with Impact has transformed the way I plan my professional future. The introductory course on Global Catastrophic Risks (GCR) and the mentoring program provided me with comprehensive and in-depth view on topics that have been little explored and that, in many cases, are scarcely shared within key disciplines. My area of expertise, anthropology, has much to contribute to the field of risk prevention and management.

In a world that has just gone through a pandemic with palpable consequences, an urgent question arises: as a species, are we really prepared to face another existential risk? These questions awakened in me the interest to continue deepening in the management of RCG and in the social dissemination of these issues. As for the terminal area of my choice, I am convinced that the social sciences have a fundamental role to play in the development of technologies such as AI, and I want to contribute significantly to this field throughout my professional career.

Through Carreras con Impacto, I was able to put my knowledge to the test, confront what I didn’t know, and pursue what I wanted to learn. It has been a journey full of ups and downs, with a touch of stress and excitement—just like any research project. Yet, at the end of this path lies an experience rich in learning. It has been truly rewarding to learn alongside a team of experts in their respective fields—people who are not only knowledgeable but also deeply empathetic to the challenges that can arise in everyday life.

I am deeply grateful for this experience.