Quick Intro: My name is Strad and I am a new grad working in tech wanting to learn and write more about AI safety and how tech will effect our future. I'm trying to challenge myself to write a short article a day to get back into writing. Would love any feedback on the article and any advice on writing in this field!

In order for an LLM to generate proper outputs, it has to find a way to understand the concepts that give words meaning. In theory, there are many possible ways an LLM could do this.

Through empirical research on AI interpretability, an interesting hypothesis arose which helps explain a possible structure that LLMs map concepts onto in order to encode their meanings. This is known as the “Linear Representation Hypothesis.”

This article is the first in a two-part series giving a high-level overview of a foundational paper on the topic, ‘The Linear Representation Hypothesis and the Geometry of Large Language Models.”

What is the “Linear Representation Hypothesis?”

The Linear Representation Hypothesis (LRH) claims that the meaning behind high-level concepts (gender, language, tense, etc.) in an LLM is represented linearly by directions within a representation space.

Up until the writing of the paper, there was no unified definition of what linear representation actually meant. The paper lays out the three forms in which linear representation was usually discussed.

- Subspace — This is the simple idea that concepts are represented by directions. A common empirical example used to demonstrate this view is the fact that the difference vector between the words “man” and “women” is approximately parallel to the difference vector between the words “king” and “queen.” Here the only concept in which the two pairs of words differ is gender, hence the difference vectors point in the same, gender-encoding, direction.

- Measurement — This is the idea that certain directions act like detectors. For example, if you project a sentence onto the “French vs English” direction, French sentences land on one side and English sentences land on the other.

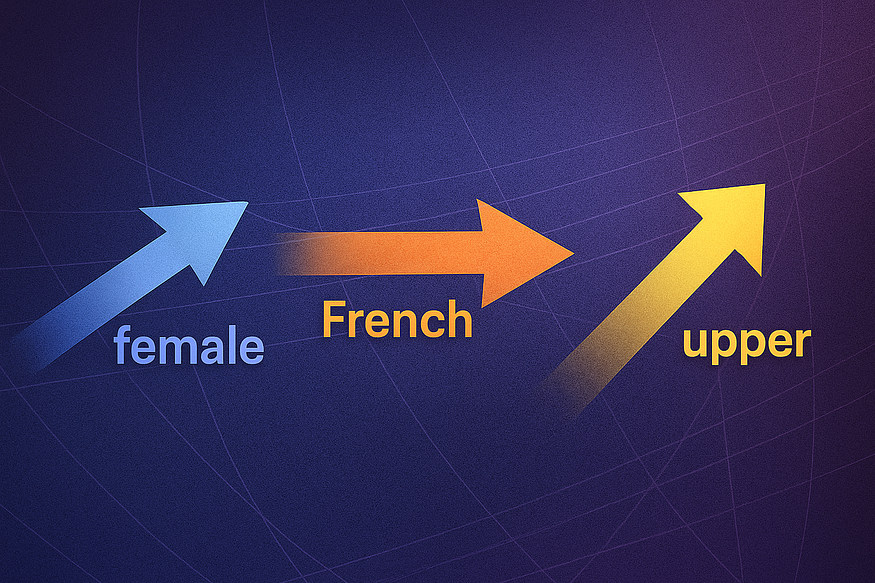

- Intervention — This is the idea that a model’s probable output to a given input can be altered in a reliable way simply by adding the desired concept’s direction vector to the input. For example, a common output to the sentence fragment “He is the…” is the word “king.” Intervention says by adding the direction vector that represents female to this sentence fragment, you can alter the model’s output to be “queen.”

Before this paper, it was unclear how these three forms of linear representation related. What made this paper foundational in the field of interpretability was its rigorous formalization of linear representation which mathematically unified the three forms. This meant that if one of these forms was true, than all of them were, under the right inner product.

What is The Right Inner Product?

To understand the inner product, an understanding of the embedding and unembedding spaces discussed in the paper is useful.

The embedding space represents the space in which an LLM encodes the meanings behind the inputs it receives. The unembedding space is where the model stores a direction for every word, so it can turn its internal thoughts into actual language. Given an input, the LLM picks the next best word by choosing the unembedding vector whose direction aligns most with the given input’s vector in the embedding space.

This alignment between vectors in the embedding and unembedding space is determined using an inner product, which is just a simple linear calculation that measures how well two directions line up.

Experiments to Support the Linear Representation Hypothesis

Not only were the authors of the paper able to provide a mathematical unification of the three forms of linear representation, they were also able to demonstrate each form empirically through four different experiments using the LLaMA-2 model.

The first two experiments helped demonstrate the subspace form of the LRH. The first experiment gathered 27 concepts. These where represented by a set of word pairs in which the two words only differed by a given concept. For example a set for the concept of “gender” might consist of word pairs like (man, women), (king, queen), and (uncle, aunt).

Then for each word pair in a concept’s set, the difference between their unembedding vectors was determined. Since these word pairs only differ by one concept, their difference vectors should all point the same direction based on the LRH. The experiment found that for all concepts tested, their associated difference vectors approximately pointed in the same direction, giving credence to the subspace form of the LRH.

The second experiment went a step further and calculated the inner product between all of these concepts. Concepts that are unrelated to each other should get an inner product close to 0, meaning their direction vectors are approximately perpendicular. This makes sense because unrelated concepts should not have any effect on each other. Sure enough, the second experiment saw very good coherence to this rule.

The third experiment helped demonstrate the measurement form of the LRH. In this experiment, researchers isolated the direction vector within the unembedding space that represented going from French to Spanish. This was done by averaging the difference between the unembedding vectors of word pairs containing French and Spanish versions of the same word.

Then, they took the inner product between this direction vector and the vectors of French and Spanish sentences in the embedding space. The inner products of French vs Spanish sentences formed clear distinct clusters showing that the direction properly measured which language was present in each sentence. The same thing was done with the direction vector representing “male to female.” In this case, no clear clusters of inner products formed, which makes sense since gender does not distinguish French from Spanish sentences. This confirmed that measurement is concept-specific.

The last experiment helped demonstrate the intervention form of the LRH. In this experiment, the researchers took direction vectors from the unembedding space (“man to women,” “lowercase to uppercase”). Then, they took input embedding vectors along with their associated outputs. They found, by adding the direction vector representing a given concept to the input vector, they where able to change the model’s output in concordance with that concept.

In one example, they found that they could take the input “He is the…,” which output “king,” and change the output to “queen” by adding the “man to women” direction vector. They where also able to change the capitalization of the word “king” to “King” by adding the direction vector for capitalization.

The crucial result of this experiment was that the addition of these direction vectors did not result in the changing of any unrelated concepts within the input. The gender vector did not interfere with the capitalization of the output and vice versa. This shows that not only could you steer a model’s output just by adding the direction vector of a given concept, but you could also do so reliably without changing other concepts, confirming the intervention form of the LRH.

But Wait…

All of these experiments where done using a newly crafted inner product called the causal inner product. This was done because the standard Euclidean dot product does not properly measure alignment between embedding vectors and unembedding vectors. In part 2 of this overview, we’ll look into why this is, what the causal inner product is, how it solves the problem, and how the researchers created it.