Most of the public discussions about AI safety seem to assume that there is only one plausible path for AI development: from narrow, specialized AI to broad AGI to superintelligence. So we seemingly have to decide between an amazing future with AGI at the risk that it will destroy the world or a future where most of humanity’s potential is untapped and sooner or later we get destroyed by a catastrophe that we could have averted with AGI. I think this is wrong. I believe that even if we assume that we’ll never solve alignment, we can have an amazing future without the existential risks that come with a superintelligent, self-improving AGI.

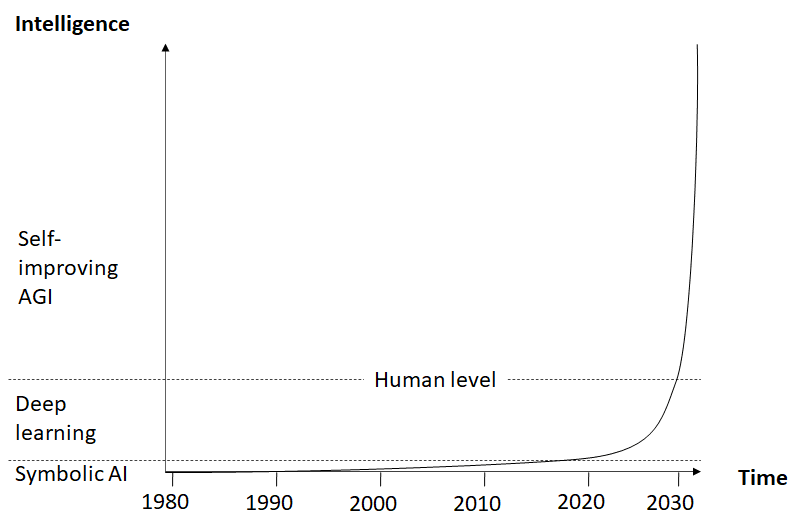

As Irving J. Good has stated long ago, an AGI would likely be able to self-improve, leading to an intelligence explosion. The resulting superintelligence would combine the capabilities of all the narrow AIs we could ever develop. Very likely it could do many things that aren’t possible even with a network of specialized narrow AIs. So, from an intelligence perspective, self-improving AGI is clearly superior to narrow AI (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: AI development (hypothetical)

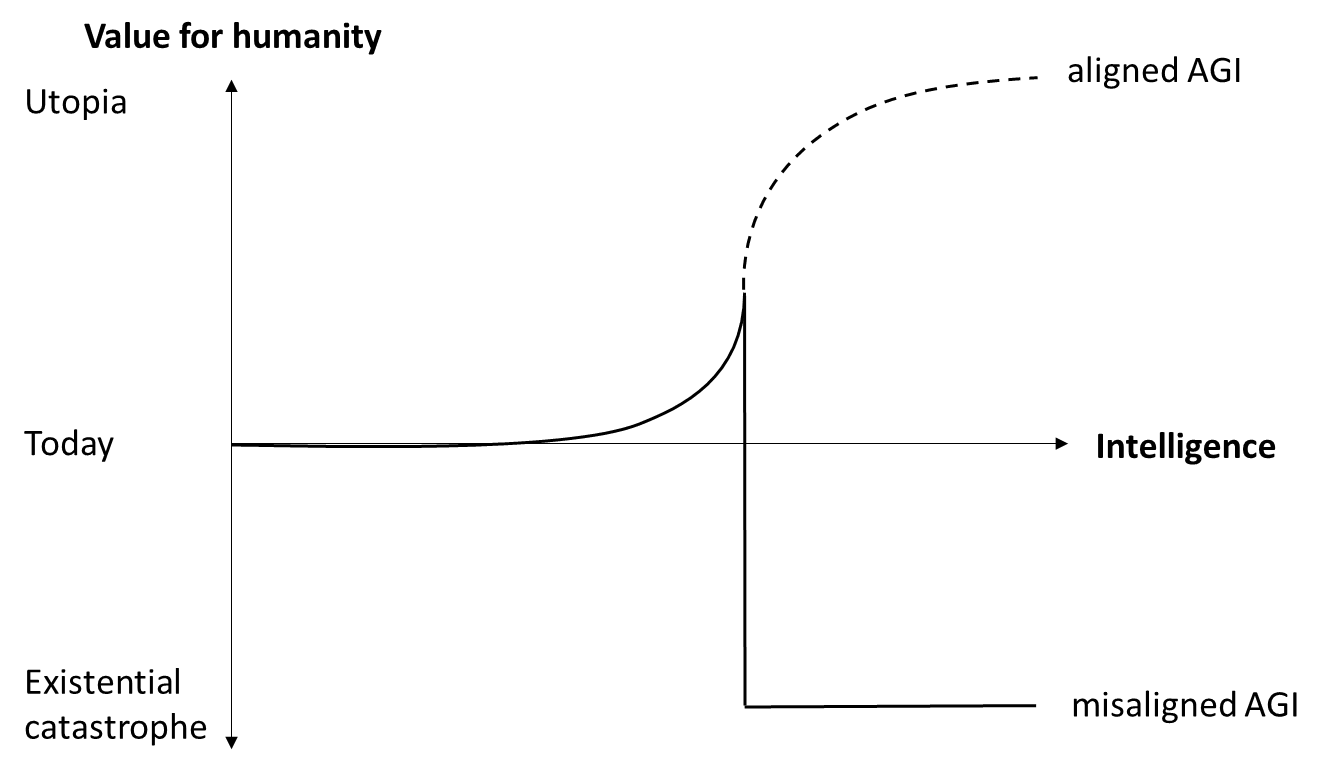

But of course there’s a catch: a self-improving AGI will be uncontrollable by humans and we have no idea how to make sure that it will pursue a beneficial goal, so in all likelihood this will lead to an existential catastrophe. With the prospect of AGI becoming achievable within the next few years, it seems very unlikely that we’ll solve alignment before that. So, from a human values perspective, a very different picture emerges: above a certain level of intelligence, the expected value of a misaligned AGI will be hugely negative (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Value for humanity of aligned and misaligned AGI

The only sure way to avoid an existential catastrophe from misaligned AGI is to not develop one. As long as we haven’t solved alignment, this means not developing AGI at all. Therefore, many people call for an AGI moratorium or even a full stop in AI development, at least until we have found a solution to the alignment problem. I personally support an AGI moratorium. I have signed the open letter of the Future of Life Institute although I think 6 months are nowhere near enough time to solve the problems associated with AGI, simply because a 6 months pause is better than just racing full-speed ahead and I view the coordination required for that as a potentially good start.

However, I think we need more than that. I think we need a strategic shift in AI development away from general intelligence towards powerful narrow AI. My hypothesis is that provably aligning a self-improving AGI to human values is theoretically and practically impossible. But even if I’m wrong about that, I don’t think that we need AGI to create an amazing future for humanity. Narrow AI is a much safer way into that future.

All technical advances we have made so far were for particular, relatively narrow purposes. A car can’t fly while a plane or helicopter isn’t practical to get you to the supermarket. Passenger drones might bridge that gap one day, but they won’t be able to cook dinner for us, wash the dishes, or clean the laundry - we have other kinds of specialized technical solutions for that. Electricity, for instance, has a broad range of applications, so it could be seen as a general purpose technology, but many different specialized technologies are needed to effectively generate, distribute, and use it. Still, we live in a world that would look amazing and even magical to someone from the 17th century.

There’s no reason to assume that we’re anywhere near the limit of the value we can get out of specialized technology. There are huge untapped potentials in transportation, industry, energy generation, and medicine, to name but a few. Specialized technology could help us reduce climate change, prolong our lives, colonize space, and spread through the galaxy. It can literally carry us very, very far.

The same is true for specialized AI: self-driving cars, automated production, cures for most diseases, and many other benefits are within reach even without AGI. While LLMs have gained much attention recently, I personally think that the value for humanity of a specialized AI like AlphaFold that can accelerate medicine and help save millions of lives is actually much greater. A system of specialized narrow AIs interacting with each other and with humans could achieve almost anything for us, including inventing new technologies and advancing science.

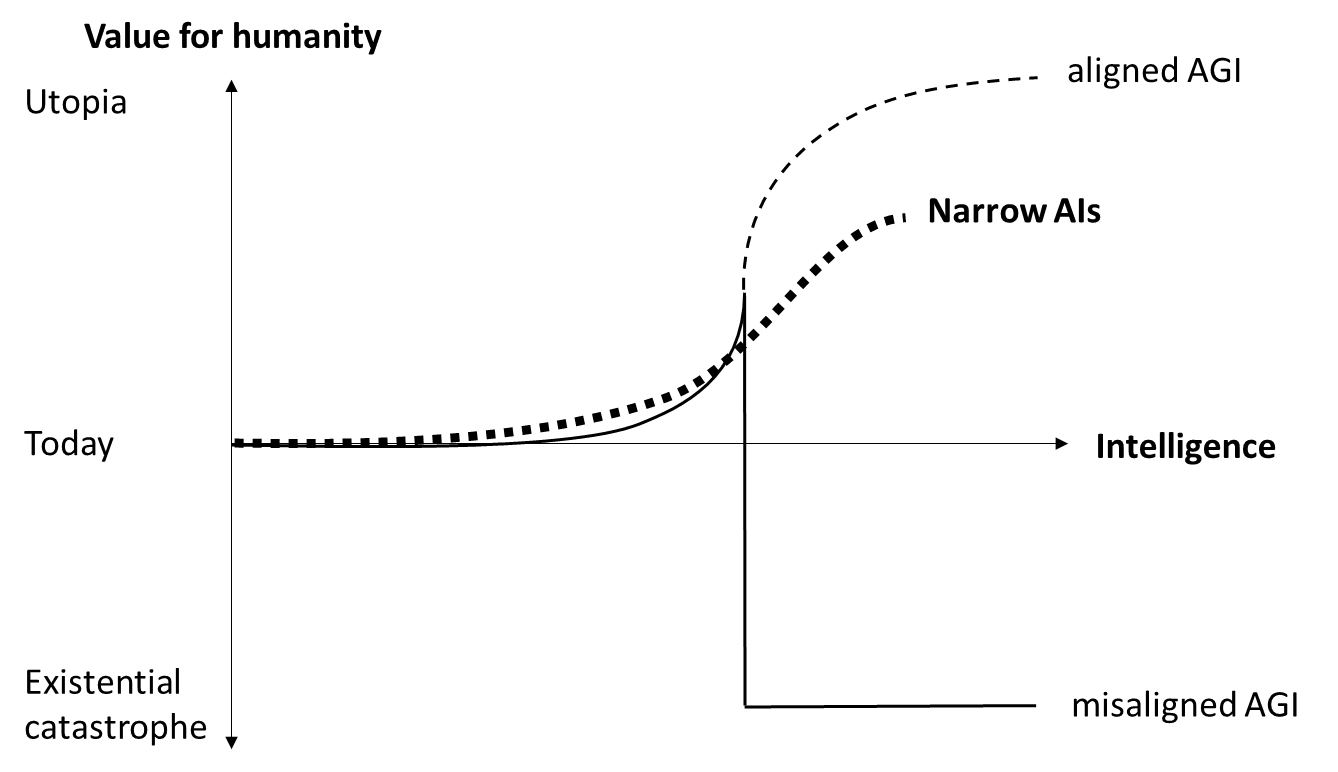

The big advantage of narrow AI is that, unlike AGI, it will not be uncontrollable by default. An AI like AlphaFold doesn’t need a general world model that includes itself, so it will never develop self-awareness and won’t pursue instrumental sub-goals like power-seeking and self-preservation. Instrumental goals are a side effect of general intelligence, not of specialized systems[1]. With the combined superhuman capabilities of many different specialized AIs we can go beyond the intelligence threshold that would make an AGI uncontrollable and gain huge value without destroying our future (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Combined value of narrow AIs vs. value of AGI

As described earlier, even a system of many different narrow AIs will be no match for one self-improving AGI. So if we restrict ourselves to narrow AI, we might never get the value out of AI that would theoretically be possible with a superintelligent, aligned AGI. It may also be harder and more costly to develop all those specialized AIs, compared to one superintelligent AGI that would do all further improvement by itself. But we could still achieve a much better world state than we have today, and a better one than we can achieve with AGI before it becomes uncontrollable. As long as we haven’t solved the alignment problem in a provable, practical way, focusing on narrow AIs is clearly superior to continuing the race for AGI.

Of course, narrow AI could still be very dangerous. For example, it could help bad actors develop devastating weapons of mass destruction, enable Orwellian dystopias, or accidentally cause catastrophes of many different kinds. There is also the possibility that a system of interacting narrow AIs could in combination form an AGI-like structure that could develop instrumental goals, self-improve, and become uncontrollable. Or we could end up in a complex world we don’t understand anymore, consisting of interacting subsystems optimizing for some local variables and finally causing a systemic breakdown as Paul Christiano described it in his “going out with a whimper”-scenario.

To achieve a better future with narrow AI, we must therefore still proceed cautiously. For example, we must make sure that no system or set of systems will ever develop the combination of strategic self-awareness and agentic planning capabilities that leads to instrumental goals and power-seeking. Also, we will need to avoid the many different ways narrow AI can lead to bad outcomes. We need solid safety regimes, security measures, and appropriate regulation. This is a complex topic and a lot of research remains to be done.

But compared to a superintelligent AGI that we don’t even begin to understand and that would almost certainly destroy our future, these problems seem much more manageable. In most cases, narrow AI only works in combination with humans who give it a specific problem to work on and apply the results in some way. This means that to control narrow AI, we need to control the humans who develop and apply it – something that’s difficult enough, but probably not impossible.

The discussion about AI safety often seems quite polarized: AGI proponents call people concerned about existential risks “doomers” and sometimes ridicule them. Many seem to think that without AGI, humanity will never have a bright future. On the other hand, many members of the AI safety community tend to equate any progress in AI capabilities with an increase in catastrophic risks. But maybe there is a middle ground. Maybe by shifting our focus to narrow AI, at least until we know how to provably align a superintelligent AGI, we can develop super-powerful technology that doesn’t have a high probability of destroying our future.

As Sam Altman put it in his recent interview with Lex Fridman: “The thing that I’m so excited about is not that it’s a system that kind of goes off and does its own thing but that it’s this tool that humans are using in this feedback loop … I’m excited about a world where AI is an extension of human will and an amplifier of our abilities and this like most useful tool yet created, and that is certainly how people are using it … Maybe we never build AGI but we just make humans super great. Still a huge win.”

Many questions about this remain open. But I think the option of ending the current race for AGI and instead focusing on narrow AI at least deserves a thorough discussion.

- ^

It is of course possible that certain specialized AIs follow goals like power-seeking and self-preservation if they are trained to do so, for example military systems.

Thank you very much! The cell comparison is very interesting.