TLDR: GiveWell can be overestimating AMF net use by about 10 percentage points (90%-80%).

Net use weighted average based on 2020 data: 78%

According to Summary of AMF PDM results and methods [2020] (public) (edited copy) (cited by GiveWell in April 2022), 78.04% of nets of past AMF distributions are hanging (weighted average of “Nets received” and “% hanging” in the “Results: Net presence” tab).

Use of post-distribution survey data to approximate net use

A more accurate result could be obtained by collecting the net usage and distribution size data (and calculating a weighted average for net use percentage) from the AMF post-distribution reports. Post-distribution surveys have not been added to the AMF Distributions page since 2018 (filtering for “Distribution complete”, “Only those with surveys”). However, net usage data should be available for all distributions: “Approximately 5% of the nets distributed are assessed through visits to randomly selected households.” Another document cited by GiveWell suggests that AMF assesses net usage in 1.5% of households (commonly about 25 households per village) (and re-assesses 5% of the 1.5% for data quality).

Net use decrease over time possibility

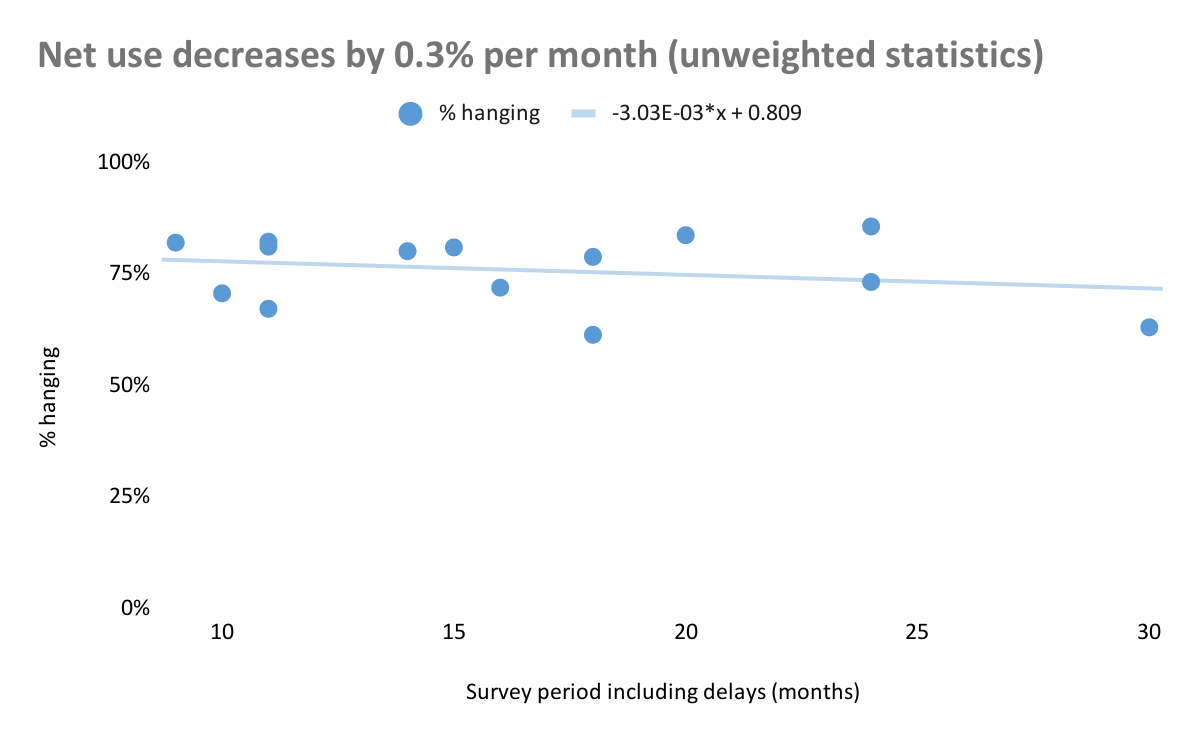

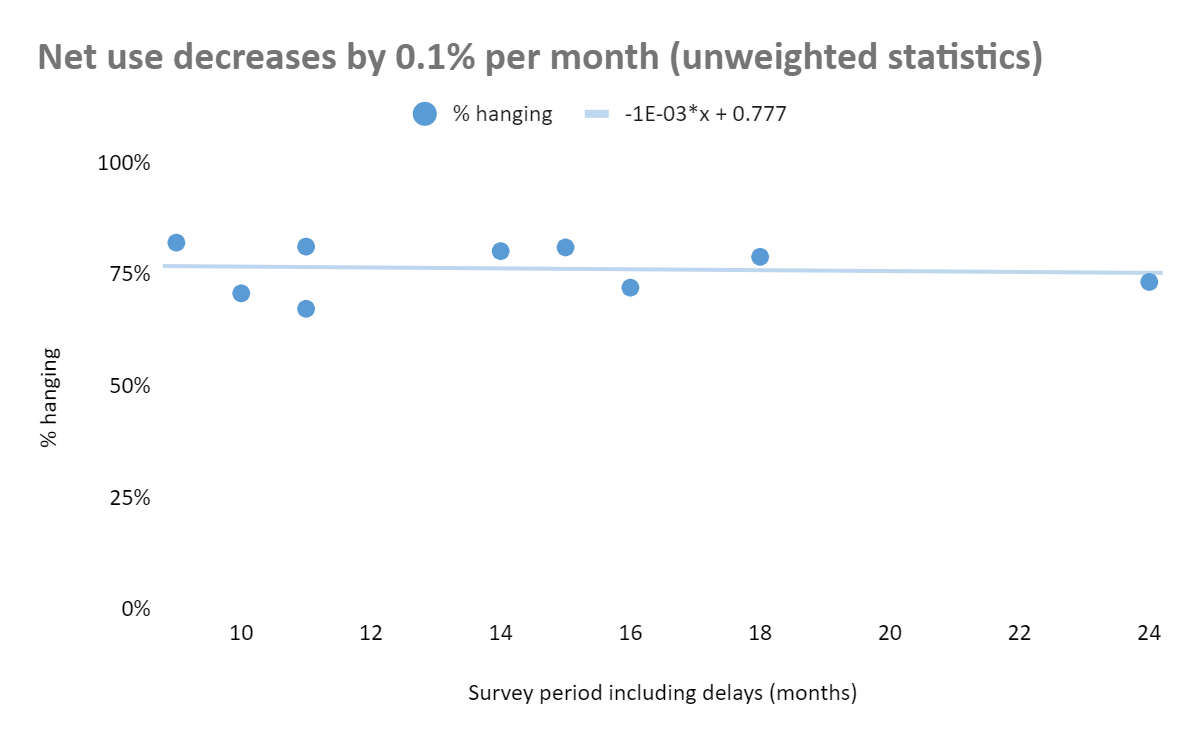

Net use could decrease over time, as the nets are worn out. Significant decrease could require an integral approximation of net use. However, data shows that bednet use does not decrease significantly over time (using unweighted statistics, net use decreases by about 0.3% per month or by about 0.1% per month, if a 30-month outlier is not used). Thus, net use values from surveys conducted anytime between about 9 and 24 months post-distribution could be used. About 2.7% of nets is worn out between 9 and 11 months post-distribution. Thus, data collected earlier than 9 months post-distribution can approximate average net usage over 24 months post-distribution with the accuracy of low units of percentage points.

GiveWell cost-effectiveness analysis net use approximation: 90%

In its cost-effectiveness analysis, GiveWell uses 90% for AMF net use (line 50). Different (including more than 10 years old) resources are cited. Based on my review of some of the studies (not AMF reports), 90% use may be a slight overestimate. However, a more comprehensive and less biased reading of relevant literature, such as by an automated software, can better inform the average net use value, among distributions funded by AMF and by other actors.

Difference between GiveWell approximation and interpretation of empirical evidence

AMF post-distribution reports suggest that about 78% of AMF nets are used (this can be about 2.7% higher before any nets are worn out). Literature values and trends can be further examined. Expected net use based on past evidence and general trends, as well as any programs which can affect use patterns can be incorporated in GiveWell analyses. Currently, it seems that GiveWell can be overestimating net use by about 10 percentage points (90%-80%).

Conclusion

Empirical evidence suggests that GiveWell could be overestimating the AMF net use by about 10 percentage points (90%-80%). Further analysis of AMF post-distribution data, relevant literature, and net use factors is needed to better approximate expected AMF net use rates.

Jonas here, AMF software engineer.

Thank you for your research! I would really like to publish more of AMF's PDM data to enable this kind of work. Unfortunately, we have to prioritize how we spend our time in the small AMF team, and this task hasn't made it to the top yet.

If you were interested in doing a more in-depth analysis (and have the time required for this) it might be good to let Rob (our CEO) know. This can help in prioritizing this type of task.

Done, thanks.

Hi, brb243! Would you please submit your contest entry via the form here? You can include a link to this post in the form if you like, or submit a Google doc link or upload a Word doc. Full contest guidelines here. Thanks so much for participating!

Best,

Miranda