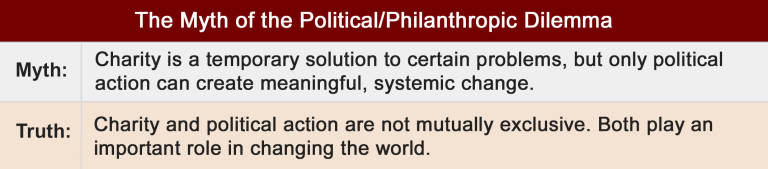

A common criticism of effective altruism is that it neglects political action and institutional change in favour of philanthropy, which can't solve the world's most fundamental problems on its own. Many argue that, rather than giving to charity, we should focus on achieving systemic change through political action.[1]

It's true that political action is a necessary step towards achieving meaningful, lasting change. However, the dichotomy between political action and philanthropy is a false one. Both play an important role in improving the world, and they can be mutually beneficial.

The Importance of Political Action

Giving What We Can appreciates the important need for political action. In some circumstances, political action is more appropriate and effective than donating to charity. For instance, regarding the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, Giving What We Can Co-Founder Will MacAskill argued that lobbying for changes in immigration policy was the most effective way to help refugees. "Donations can be helpful but are unsustainable in this instance," he wrote, "whereas political action could bring about real change." On the 80,000 Hours blog, Director of Research Rob Wiblin provides nine more examples of effective altruist individuals and organisations working towards systemic change.

The Importance of Charity

Charity, however, can also play an important role in improving the world. It can help improve lives directly by, for example, providing support to low-income communities. There are some highly effective charities that alleviate suffering, reduce the burdens of disease, and help children receive an education. These are amazing giving opportunities, and many of them will have a lasting impact.

In order to advocate for political change, basic needs must first be met. In communities suffering from poverty and/or disease, political action is unlikely to be a priority. Donations can lift individuals out of dire circumstances, giving them greater autonomy and enabling them to play a larger part in their community's politics, if they so desire. Indeed, many of the outcomes we associate with political action can be achieved by increasing the health and well-being of low-income communities.

In addition to directly helping individuals and communities, giving to charity can also support political or institutional change. Donations to advocacy organisations or campaigns, for instance, can play an important role in changing public opinion, which is frequently a necessary precursor to political mobilisation.

Effective Giving Opportunities

There are many highly effective charities that advocate for institutional change. For instance, the Clean Air Task Force engages in legal and legislative advocacy to support climate-friendly policy change. The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security works with policymakers to prepare for threats to public health. The Nuclear Threat Initiative works with political leaders across the world to improve global nuclear policy. The Good Food Institute, in addition to developing and promoting alternatives to animal products, is working to secure fair policy and public funding for research to develop a more sustainable global food system.

You can help improve — and even save — lives by donating to one of many highly effective organisations. Consider making a giving pledge and joining our worldwide community of like-minded people who are working to make the world a better place.

This post is part of a series on common myths and misconceptions about charity. Taking time to learn the facts will help prevent the spread of misinformation and inspire more people to use their resources effectively to improve the world.

Multiple authors contributed to writing and editing this post.

I realise that these articles are meant for a popular audience. However, I was surprised to see this extremely strong claim - the idea that meaningful and lasting change is literally impossible without political action - asserted without any evidence, as if it were self-evident. If anything it seems self-evidently false to me.

For a small-scale example, consider rescuing the archetypal child drowning in a pond. Saving the child is meaningful; doing so might be one of the best things you ever do in your entire life. And the child might easily live another 80 years, outlasting many policies and countries, not to mention the potential for the child to one day have their own children, so it seems like a lasting change. Just because it isn't political doesn't mean we should dismiss this.

For a much larger impact, consider Norman Borlaug. His scientific work on new crop varieties hugely increased our capacity to produce food; the common quote that he saved a billion people is probably an exaggeration, but this work clearly had an extraordinarily positive impact on many millions of people. It is true that he did work with governments, but the core of his achievement was scientific, not 'political action'.

Closer to home, consider GWWC itself. I suspect you would agree that GWWC has had a very meaningful impact, and GWWC, the EA movement it spawned, and the downstream consequences, seem likely to persist for some time. Yet even though some GWWC members have tried to influence politics, the central impacts and original motivation was about individual contributions, not political lobbying.

Indeed, this claim is directly contradicted later in the article:

Overall I feel like this article bends over backward to be positive towards political action. Even the 'Importance of Charity' section spends around 2/3 of the time talking about why charity is good for politics, which seems very misleading. Yes, if we save a girl from malaria, maybe she will grow up to be a politician... but that's not why we donate to AMF. We donate because malaria is bad and causes a lot of suffering directly. I would rather see this section focus on the core, true reason, rather than a rather tertiary one. Not only would this be more honest, I also think it would be more persuasive.

I think a more balanced approach also would include criticism of demagoguery, including perhaps some of the points mentioned here. Your aim should not just be to merely persuade the reader that charity is acceptable, but that the types of charity we support are significantly better than most popular political causes. After all, often political action leads to meaningful and lasting negative change!

When I first read it, I assumed that "meaningful, lasting change" meant "all the kinds of changes we want," rather than "any particular change." Maybe that's what the authors intended. But on rereading I think your interpretation is more correct.

This (and the infographic that follows) seem quite contradictory to me -- first stating it is a false dichotomy but then reinforcing that false dichotomy but describing the two as distinct components that can be complementary.

The article then later focuses on what seems the stronger evidence of the false dichotomy claim -- showing how lots of giving opportunities EAs focus on are very political, i.e. that the critique does not really apply, when you decide for high-impact charity you might very well decide to focus on high-impact charity working on systemic change.