This is the full text of a post from "The Obsolete Newsletter," a Substack that I write about the intersection of capitalism, geopolitics, and artificial intelligence. I’m a freelance journalist and the author of a forthcoming book called Obsolete: Power, Profit, and the Race to Build Machine Superintelligence. Consider subscribing to stay up to date with my work.

If you've been following the headlines about Elon Musk's lawsuit against OpenAI, you might think he just suffered a major defeat.

On Tuesday, California District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers denied all of Musk's requests for a preliminary injunction, which would have blocked OpenAI's restructuring from nonprofit to for-profit. Judge Rogers also expedited the trial, which will now begin this Fall. Media outlets quickly framed this as a loss for Musk.

But a closer reading of the 16-page ruling reveals something more subtle — and still a giant potential wrench in OpenAI's plans to transfer control of the company from the nonprofit board to a new for-profit public benefit corporation.

If the company fails to complete this transformation by October 2026, investors in its $6.6 billion funding round last October can ask for their money back.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, nonprofit board director Bret Taylor, and the company's press office did not reply to requests for comment.

In a narrow sense, Musk did "lose." However, as Judge Rogers notes, the bar for a preliminary injunction is extremely high. To surpass it, both the facts of the case and the legal questions involved have to clearly point in the same direction.

Therefore, it would have been extremely surprising if the judge granted the injunction. She did, however, stop just short of it.

Does Musk have standing?

To bring a lawsuit, you have to have standing, i.e. you have to convince the court that you've been harmed by the actions of the defendant. For most of the claims Musk brought, Judge Rogers thinks that he doesn't have standing.

But Musk's third claim is that his donation of $44 million to OpenAI was contingent on his expectation that the organization remain a nonprofit. The legal question is whether Musk's donation meant that he entered into a "charitable trust" with OpenAI, in which he expressly meant for his gift to only be used if the organization remained a nonprofit.

Unfortunately for Musk (and fortunately for OpenAI), there is no contract or gift agreement documenting any restrictions on the gift. Judge Rogers says that this question is a "toss-up," citing evidence that points in both directions. (OpenAI published emails showing Musk was aware of and on board with the transition to a for profit, which makes him far less sympathetic here.)

So why does this ruling matter? Well, while Judge Rogers found Musk's standing uncertain at this preliminary stage, she went out of her way to signal that the core claim — that OpenAI's conversion violates its charitable purpose — could have merit if properly brought before the court.

Put differently, Judge Rogers essentially writes that if Musk clearly had standing, the injunction would be justified. Here's the key quote from her judgment:

if a trust was created, the balance of equities would certainly tip towards plaintiffs in the context of a breach. As Altman and Brockman made foundational commitments foreswearing any intent to use OpenAI as a vehicle to enrich themselves, the Court finds no inequity in an injunction that seeks to preserve the status quo of OpenAI’s corporate form as long as the process proceeds in an expedited manner. [emphasis original]

Legal experts who have followed the case closely see this ruling as far more significant than the headlines suggest — a decision that invites other existential challenges to OpenAI's conversion efforts.

"This is a big win for Musk," says Michael Dorff, the executive director of the Lowell Milken Institute for Business, Law, and Policy at UCLA. "Even though he didn't get the preliminary injunction, the fact that there is a pending trial on this issue and that his claim wasn't denied is a pretty big impediment to [OpenAI] moving forward expeditiously," he says.

A former OpenAI employee spelled out the significance of the judgment, telling Obsolete:

I think this is unusual, which is why it's noteworthy. Typically courts decide cases on the narrowest grounds possible. So if the standing decision is sufficient to deny, then none of the discussion about the underlying merits is decision-relevant. When courts do this, it's usually done with purpose.

If Musk was deemed to have standing, the former employee said the chances of the lawsuit prevailing on the merits was, "definitely over 75%. 90% isn't crazy. The judge doesn't have all the facts at this stage. All of the judge's emphasis in her denial was on standing, not the other question."

You know who does have standing?

Unlike Musk, the Attorneys General (AGs) in California and Delaware unquestionably have standing to challenge OpenAI's conversion — a fact Judge Rogers repeatedly emphasized throughout her ruling.

"The fact that the AG has standing is by statute, so it's not a big statement," notes Dorff. "What's unusual is that the AG might actually do something about it. This may be a rare case where an AG finds it worthwhile."

The AGs in both states have already signaled interest in the case. The Delaware AG filed an amicus brief in December emphasizing that her office would scrutinize any restructuring to ensure it protects the public interest. California's AG is reportedly reviewing the conversion as well.

Judge Rogers' ruling substantially increases pressure on both AGs to take action, providing them with judicial validation that the core issues deserve serious scrutiny.

The AGs are empowered to protect the public interest and could each initiate legal action to block the restructuring, with a strong likelihood of success given their clear standing and the court's signals about the merits of this case.

It's hard to change your purpose

Dorff agrees that the case’s merits pose significant challenges to the company, echoing past conversations with three other legal experts who followed this case.

"OpenAI has a very tough road ahead of it, if Musk has standing on that claim," Dorff explains. "Changing of a nonprofit's purpose is only supposed to be possible when the original purpose is defunct. That's not the case here."

To illustrate this point, Dorff cites the example of The March of Dimes. The anti-polio foundation was able to legally shift its mission after the disease was effectively eradicated. OpenAI's situation, Dorff argues, is fundamentally different.

"The original purpose was to develop AI for the benefit of all of humanity in a way that is safe," Dorff notes. "That purpose is not defunct — it's very much still ongoing."

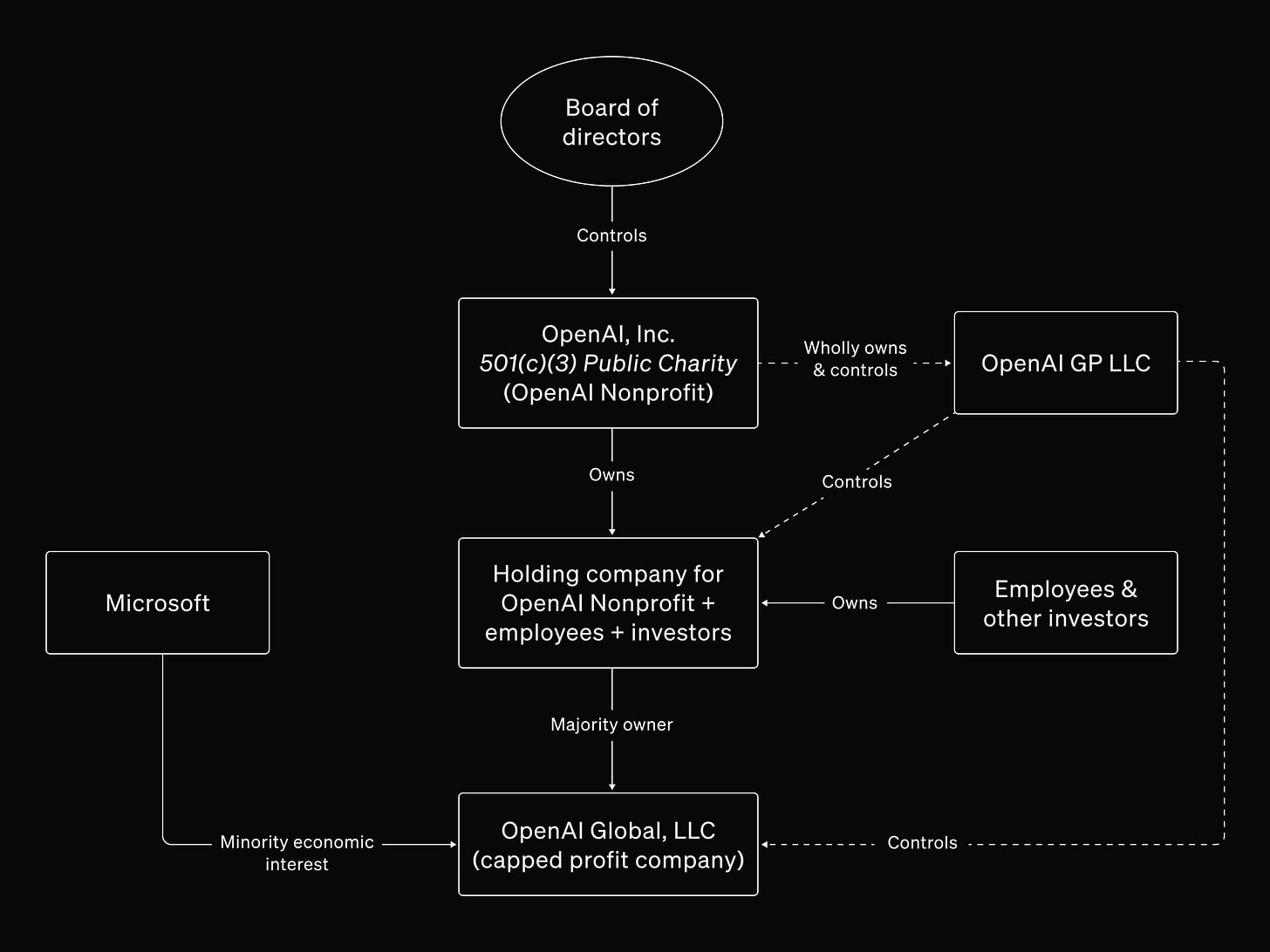

Given this, Dorff says, "It's hard to imagine a good argument for why they should be allowed to change their purpose." The nonprofit's major asset, he points out, isn't land — it's the control the board has over OpenAI the company, which is at the forefront of developing powerful AI systems. "Owning control over that entity seems uniquely well suited to the nonprofit's purpose," Dorff says. "Giving up that control, even for a lot of money, is not equivalent."

Directors could be personally liable

The judgment raises another critical issue that has received little attention: potential personal liability for OpenAI's board members if they proceed with the conversion.

"If a breach of fiduciary duty is established, board members could be personally liable," explains Dorff. "If they're conflicted and violate their duty of loyalty in favor of their own interests instead of the public interest... they could be personally liable for the true value of whatever was lost."

The former OpenAI employee concurred, "Typically when directors are acting on behalf of organizations, there's some shield — the business judgment rule." Judges are reticent to second-guess business decisions that don't pan out. This gives directors wide leeway in governing companies.

But, "Under certain circumstances that protection doesn't apply. If I were a director, I'd want to be getting legal advice right now," the ex-employee says.

OpenAI's nonprofit board (in)famously has a fiduciary duty to humanity and therefore needs to justify the conversion on those terms, which is a far taller order.

In a follow-up exchange, the former OpenAI employee wrote to Obsolete:

Judge Rogers is very clearly saying that she has serious concerns about the legality of the restructuring. So after this ruling, the directors are on heightened notice that the legality of the restructuring is open to serious doubt. If they just try to ram it through regardless, that could be a pretty egregious breach of their fiduciary duties — so egregious that they might even have personal liability.

The prospect of being personally on the hook creates an entirely different category of risk for OpenAI's leadership as they navigate the restructuring.

Why OpenAI is trying to restructure

OpenAI's unconventional structure has become an albatross for the organization as it raises the staggering amounts of money needed to keep training cutting-edge AI models. Just four months after the October funding round that valued OpenAI at $157 billion, the Wall Street Journal reported that SoftBank was planning to invest up to $25 billion at a valuation of up to $300 billion.

OpenAI was confident enough in its ability to successfully complete its restructuring within two years that it gave investors the ability to take their $6.6 billion back if it didn’t convert in time.

But Tuesday's ruling threatens this timeline, even with the new expedited trial schedule. OpenAI faces a difficult choice: attempt to proceed with the restructuring under the cloud of pending litigation and potential AG intervention, or wait for legal clarity that may not arrive until the resolution of a trial that won't even begin until the Fall of 2025 — uncomfortably close to the October 2026 deadline when investors could demand their money back.

If OpenAI fails to transition and investors come calling, finding the money might not be enough (and is far from a given — the company is burning billions a year). OpenAI's ability to attract enough investment to compete may be dependent on it being structured more like a typical company. The fact that it agreed to such onerous terms in the first place implies that it had little choice.

What happens next

Dorff says that this case "will create fodder for discussions in law schools for many years to come."

The expedited trial schedule — which he calls "highly unusual" and "very, very quick" — suggests the court recognizes both the importance and urgency of resolving these questions. While OpenAI may continue preparations for its restructuring, the ruling represents a significant yellow light that both the company and potential investors cannot ignore.

And if the California or Delaware Attorneys General decide to act on the judge's signals, that yellow light could quickly turn red.

Far from a defeat for Musk, this ruling may ultimately prove to be the most substantial obstacle to OpenAI's plans to shed its nonprofit constraints — constraints that its founders once championed as essential to developing AI that benefits humanity.

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe to The Obsolete Newsletter.

Strong upvoted. I'm definitely among the people who saw the headlines, thought that it was a simple case of Musk losing, and didn't appreciate that it's potentially much less favourable to OpenAI that it appears from the headlines.