In December 2025 President Trump, after considering sales of NVIDIA’s advanced Blackwell B30 AI chips to People’s Republic of China (PRC), announced his approval of sales of the previous generation model - H200, in exchange for sellers paying a 25% export tax. On January 13, 2026 the Bureau of Industry and Security at the Department of Commerce released a new rule regulating the sale of this and equivalent chip models.

What is H200

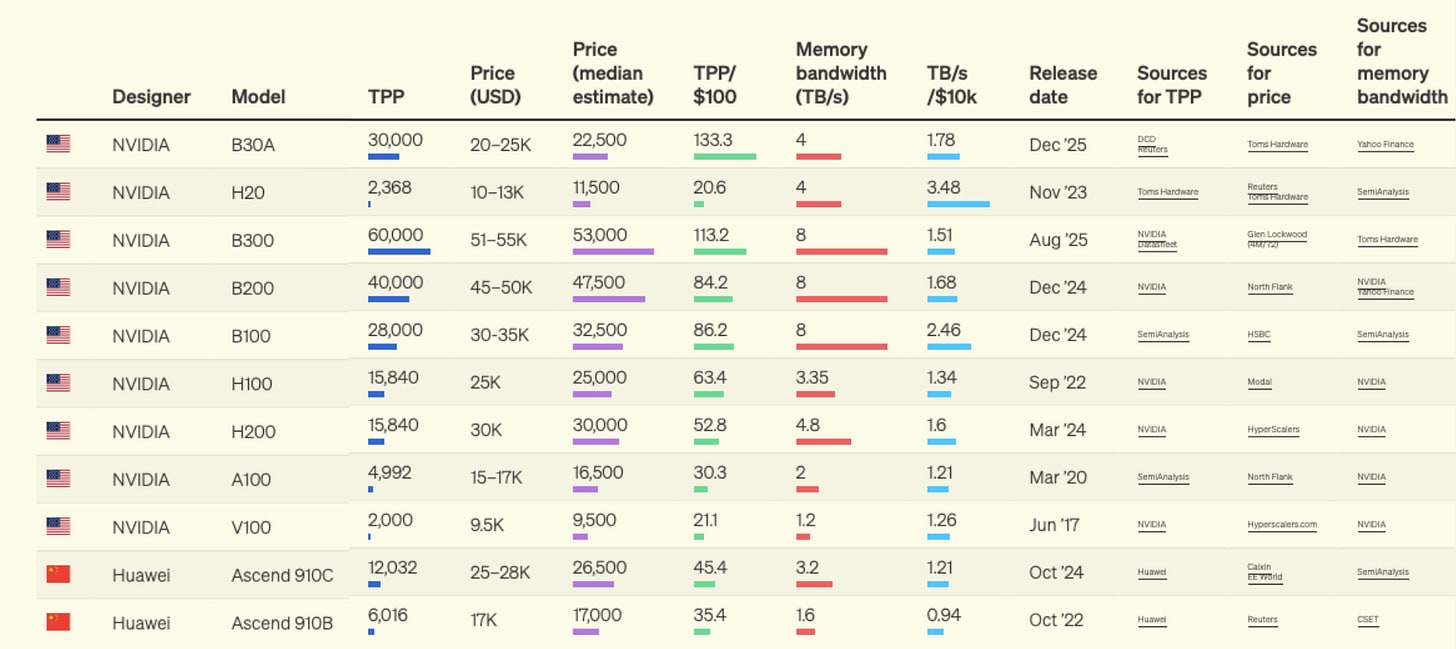

H200 is NVIDIA’s AI chip from the Hopper generation, considered the next most powerful after the newest Blackwell models, B100 - B300 (see the AI chip comparison table in Figure 1). The model was released in March 2024 and, according to an estimate by Center of American National Security (CNAS), NVIDIA may have so far sold around 2 million units of this model in the United States. While the chips are designed by NVIDIA, they are produced in Taiwan by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Figure 1. AI Chip comparison table

Source: Institute for Progress (IFP)

The new BIS licensing rule

The history of US-China tensions over AI chips is a long and convoluted one. As Donald Trump returned to office, the US export control rules had permitted shipping of NVIDIA’s H20 chips to PRC. In April 2025 the Trump administration had prohibited their export, but four months later reapproved in exchange for a 15% export fee. The Chinese government did not take that maneuver well and banned the entrance of H20s into the country, claiming that local tech firms should prioritize buying Chinese-made Huawei AI chips, as required by China’s long term strategy of its AI stack indigenization. However, some experts saw the ban as potentially a negotiation tactic to obtain access to more advanced chips. After NVIDIA’s relentless lobbying, the Trump administration gave in by approving sales to Chinese companies of H200 chips, that are six times more powerful than H20s.

On January 13, the Bureau of Industry and Security released guidelines on how exporters should go about and what requirements they should meet to obtain a license to export H200 and equivalent chips to China. The key points of the rule include the following:

- The reviewing process is altered from a presumption of denial to a case-by-case review, meaning that each application for export to China will be reviewed individually and granted if an exporter provides sufficient compliance evidence.

- The rule applies to chips with total processing power (TTP) less than 21,000 and Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) bandwidth less than 6.5 TB/s. Those thresholds include not only H200, but also other lower performance chips (see Figure 2). However, according to CNAS, NVIDIA’s H200 and AMD’s MI325X have higher chance of obtaining US government’s approval, as the Trump administration intends to charge 25% export tariffs on those two models and therefore might be more willing to grant a license.

Figure 2. Chips within BIS export threshold

Source: CNAS

- The license applicants must assure the US government that the export of chips to China won’t take up the global foundry capacity and thereby result in delaying the supply of AI chips for US tech companies. This requirement might be hard to credibly fulfill, as the existing chip fabrication facilities are already operating at full capacity and struggling to meet demand from their established customers, with TSMC meeting only a third of its demand for advanced-node output. As of January 2026, NVIDIA reportedly had 700,000 H200 chips in its inventory. After those chips are sold, it may be uncertain when the next batch of this model becomes available, assuming that TSMC would be fulfilling its existing order backlog in first-come-first serve order.

- The amount of chips eligible for export is capped, with the aggregate TPP of chips sold to China being limited to 50% of the same chips sold in the US up to date. CNAS estimates that limit to be 900,000 H200-equivalents (adding AMD’s MI325X chips into the mix). To put that number into perspective, it’s twice as much TPP as the world’s largest AI Data Center that has 470,000 H200-equivalents of compute. Another example, OpenAI’s entire deployed worldwide computing power in October 2025 was an equivalent of 1.1 million H200 chips’ TPP, which is only 22% more of what can potentially be sent to China.

- The license applicants must obtain their Chinese customers’ commitments that the chips won’t be used for:

- prohibited purposes, such as military or weapons of mass destruction.

- prohibited end users, defined as ‘military end user’ and ‘military-intelligence end user’.

However, the guidelines don’t clarify how BIS can reliably check the veracity of claims provided by Chinese customers or what punitive actions it can take if those claims turn out to be false. This lack of enforceability was reportedly the main reason why the previous administration outright banned the advanced AI chips from China.

- The rule outlines an ingenious, but legally dubious, way of collecting the 25% export fee imposed by the Trump administration on the H200 chips bound to China. The proposed solution demands license applicants to obtain a third party verification for chips destined for export, where:

- the verifying third party companies need to be certified by the US government,

- chips produced in foreign fabs (i.e. in Taiwan) need to be first shipped to the US for certification and charged 25% import tax at the customs during the entry into America.

Essentially, this solution includes shipping of the H200 chips that are manufactured in Taiwan, a strait away from China, into the United States for so-called verification, and serves as a workaround for a constitutional prohibition of an export tax, framing the 25% export fee as an import tax. According to an estimate by the Institute of AI Policy and Strategy (IAPS), the fee is not going to generate substantial revenue for the US, amounting to $6.5B, or mere 0.13% of the US tax revenue. As export taxes are unconstitutional, this workaround may be challenged in courts.

Although the new rules seem stringent, in practice they may be hard to enforce, either due to BIS’s lack of resources and legal jurisdiction in China, or the debatable legal ground for the 25% export tax. However, setting those limitations aside, IF those hurdles are overcome, how may obtaining the H200 chips impact China’s AI progress?

What can China do with a windfall of H200 chips?

If China received the 900,000 H200-equivalents from the US, the number estimated by CNAS to be permitted by the 50% cap in the BIS rule, it would significantly increase the country’s AI capabilities.

There is no clear data on the exact AI compute capacity available in China, but it’s made of a mix of domestic Huawei Ascend chips, old NVIDIA H20 chips that were bought before the export ban, and smuggled H100, H200 and Blackwell chips. As China has been banned from getting access to western-made semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME), its domestic manufacturing capability is limited, both in quality and quantity.

Huawei’s best available chip, Ascend 910C, which is believed to be illicitly made at TSMC factory in Taiwan, has only 60% performance of NVIDIA’s H100. Moreover, Huawei plans to release Ascend 960, its next generation chip with performance parameters close to H200 only in the end of 2027. So, by allowing access to H200 now, the United States may bridge the almost two year gap until China releases its own homegrown advanced chips.

Now, about the quantity, there are various estimates of how many AI chips Huawei can produce in 2026, but CNAS averages them to 390,000 H200-equivalents in terms of TPP. The injection of something between 700,000 H200 chips (currently in NVIDIA’s inventory) and 900,000 H200-equivalents (cap outlined by the BIS rule) into China’s AI ecosystem will be approximately triple amount of compute that Chinese tech firms would otherwise add up.

That is the crucial missing piece in China’s AI triad, as the country is on par with the US on other pillars - data and algorithms. It also has formidable AI research force and significantly higher electricity generation capacity for its AI data centers than the United States.

What can China do with all that extra compute? It most certainly will use it to:

- increase its economic output, integrating AI into industry, enterprise and consumer goods, in its endeavor to catch up economically to the United States;

- strengthen its domestic autocracy, boosting surveillance, censorship and propaganda, while optimizing governance;

- expand its geopolitical influence, competing with American hyperscale data centers abroad, spreading worldwide its agile AI solutions with woven in autocratic values;

- advance military innovation, in explicit violation of BIS’s prohibition, as the US has no real leverage tools to prevent repurposing of exported chips for military use, once they reach China.

Chip smuggling into China and beyond

One important aspect that is worth mentioning is chip smuggling into PRC. Experts estimate that approximately 140,000 advanced chips worth $5-7 billion were smuggled into China in 2024. The approval of H200 is not likely to curb AI chip smuggling, as China has insatiable demand for them. Smugglers may just switch their focus to more advanced NVIDIA models, such as Blackwell and Rubin, or more H100 and H200, if the BIS cap is reached. Moreover, with more availability of AI chips at home, the smuggling stream may trickle down to China’s autocratic trade partners, such as Russia and Iran. Both countries are heavily sanctioned by the US and the EU, and have rerouted their supply chains through China to circumvent the restrictions.

CNBC reported that in Q4 of 2022 87% of semiconductors that entered Russia came through Hong Kong, China. Whether through that channel or another, by late 2025 Russian IT firms have already obtained access to NVIDIA’s H200, officially prohibited from Russia by US export controls, for a locally assembled GPGPU platform and IaaS services provider.

Iran also aspires to join the global AI revolution. It has recently established a National Artificial Intelligence Organization and announced plans to build a data center for its sovereign AI project. As the country doesn’t have sufficient AI know-how or chip production capacity, to fulfill its AI ambitions it will have to import the needed compute. The pariah state doesn’t have many trade partners to turn to, so China or Russia appear to be the most likely places where Iran may source the chips.

Importantly, the leadership of both countries is dead set on destabilizing western democracies, including the United States. So, loosening access to advanced AI chips for China may boomerang back into America in a form of AI-enhanced cyber attacks and disinformation from Russia and Iran, let alone China.

Considering all the above, the decision to allow the sales of H200 chips to China may turn out to be inauspicious for America from the following standpoints:

- The AI race with China, as it decreases the existing compute gap between the two countries and thus increases PRC’s AI capabilities;

- Economic competition, as the Chinese government will apply AI capabilities into efforts to boost its economy;

- US national security, by indirectly strengthening American rivals’ interference capabilities;

- The global tug-of-war between democracies and autocracies, that tilts toward autocrats as a result of the previous point and of China’s increased ability to export its AI models with autocratic values worldwide.

As such, it is debatable whether the deal that can augment the US tax revenue by meager 0.13% is worth the risk. So far the arrangement seems to benefit only NVIDIA, Chinese tech companies and the freshly minted third party chip verification firms in the US.

Potential restraining factors

Despite all the concerns, there are several factors that may hamper the H200 sales to China. The first one is the resistance from its government, which blocked the import of the chips “unless necessary”. Some experts interpret that move as leveraging tactic to force America to release more advanced Blackwell chips to China, as it succeeded in the case of the H20 chips.

Another slowing factor may be American bureaucracy, as approvals are supposed be issued on case-by-case basis, and the underfunded and understaffed BIS may not have the bandwidth to process all the applications in a timely manner. The approvals can also be issued in a controlled fashion to be used by the Trump administration as a leverage for concessions in other trade negotiations with China.

There is also an issue with the global foundry that is struggling to meet chip production demand and leaves the possibility that the existing 700,000 H200 chips that NVIDIA currently has in its stock is all that Chinese companies will get in the foreseeable future.

Finally, the whole deal may be derailed, if the 25% export tax workaround is legally challenged.

Conclusion

There is still a lot of debate and uncertainty regarding the H200 chip export to China. However, one thing is clear: at a face value selling a large amount of advanced AI chips is disadvantageous for the US and deviates from the Trump administration’s America First motto.

As usual, the devil is in the details, and the particularities of the new BIS rule, such as unconstitutionality of export tax, the bureaucracy of verification and case-by-case licensing, as well as the existing US-China geopolitical tensions can slow down the implementation.