First published in 2022. Updated in 2024. Chapter 4 in the book “Minimalist Axiologies: Alternatives to ‘Good Minus Bad’ Views of Value”.

Readable as a standalone post.

Summary

Population axiology matters greatly for our priorities. Recently, it has been claimed that all plausible axiological views imply certain “very repugnant conclusions” (defined below in 4.1 and 4.2). In this response, I argue that minimalist views avoid these “very repugnant conclusions”, and that they face less repugnant conclusions than do offsetting views (4.4).

1. Are repugnant implications inevitable?

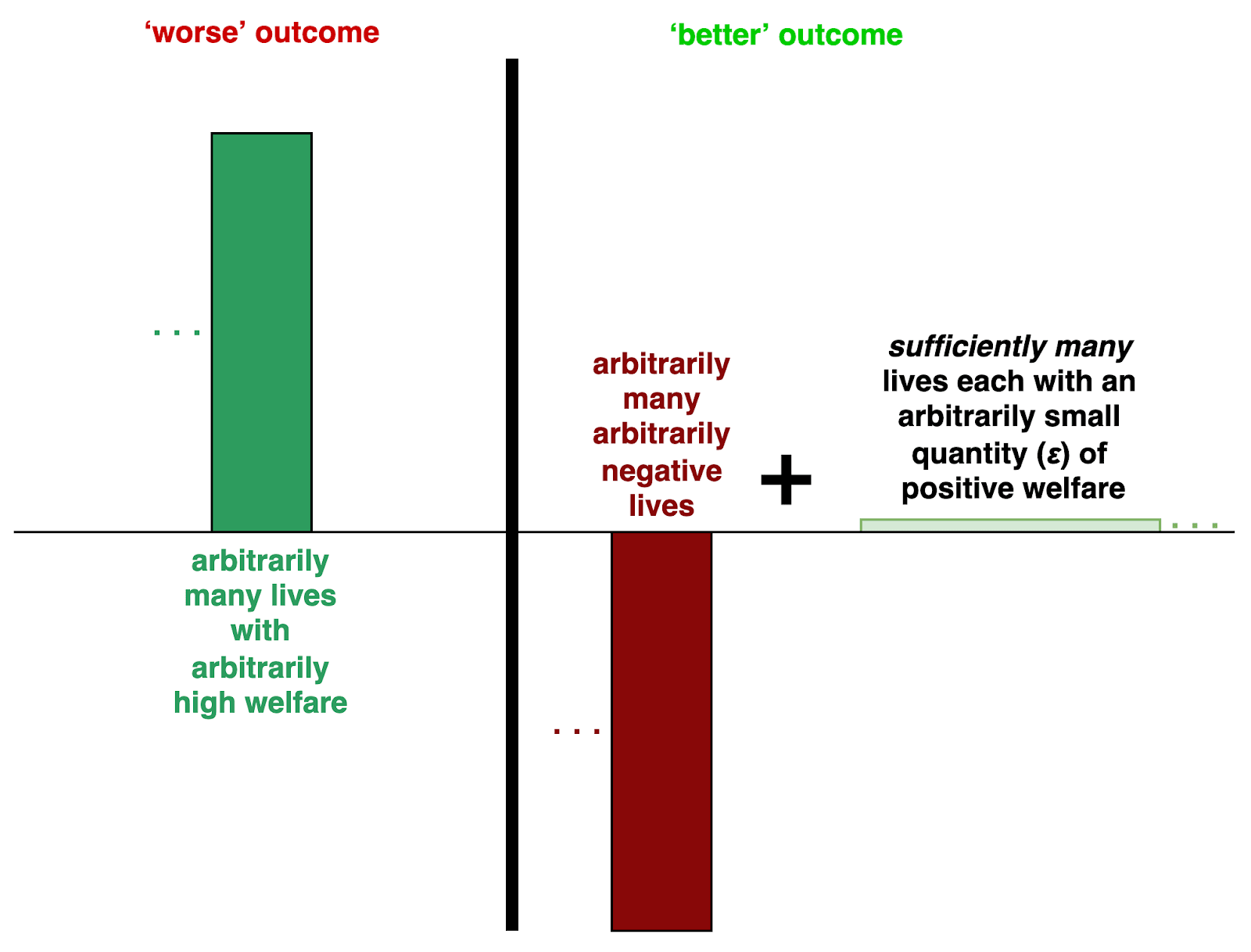

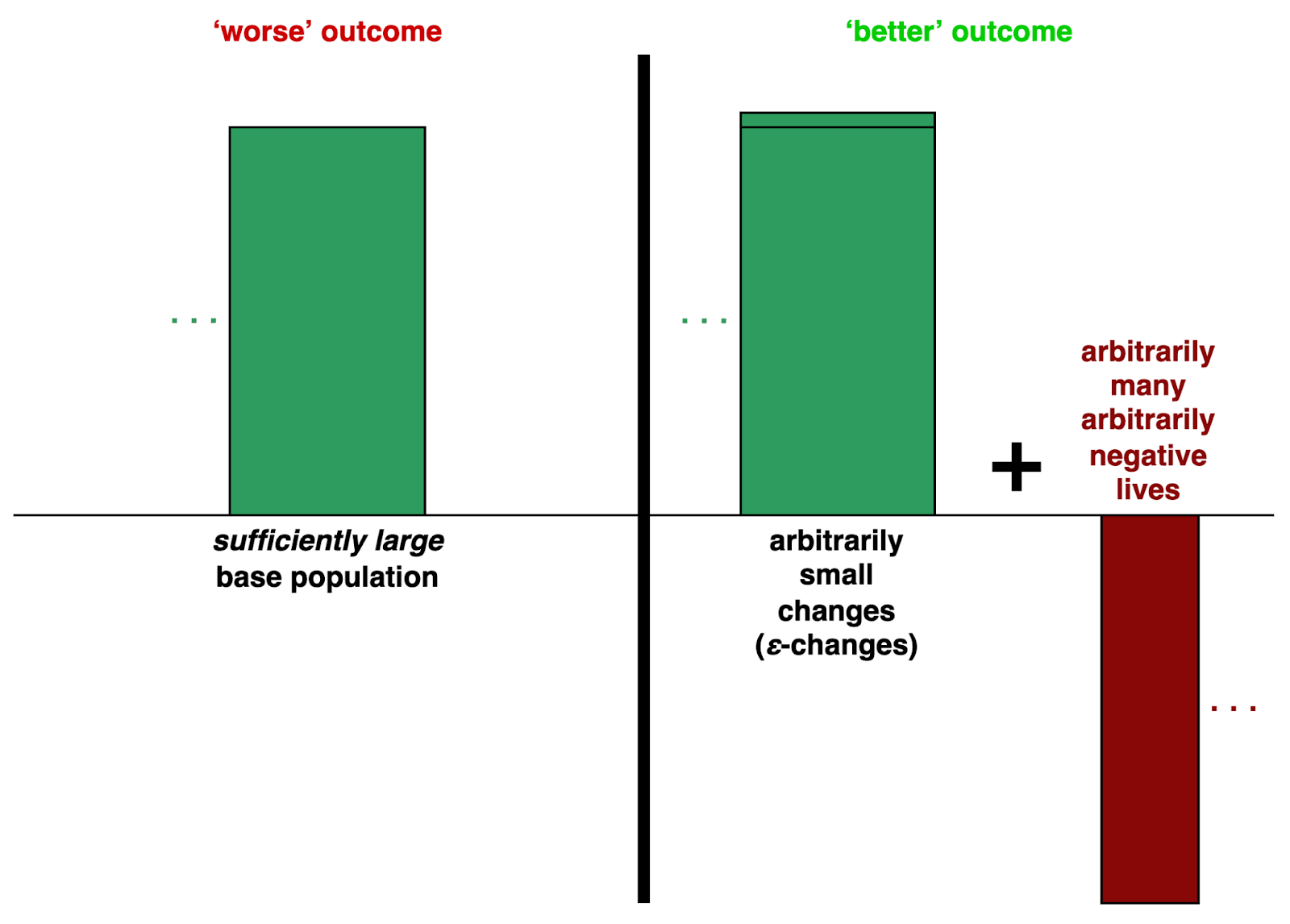

In population axiology, certain offsetting views, according to which independent bads can be offset by a sufficient amount of independent goods, face the Very Repugnant Conclusion (VRC):

| A population of arbitrarily many lives with arbitrarily high welfare is worse than a population of arbitrarily many arbitrarily negative lives plus sufficiently many “ε-lives”[1] that each have an arbitrarily small quantity of positive welfare (Figure 4.1). |

Additionally, offsetting views allow the ε-lives in the VRC to be “rollercoaster lives” that all contain unbearable suffering, purportedly counterbalanced by a sufficient amount of bliss.[2]

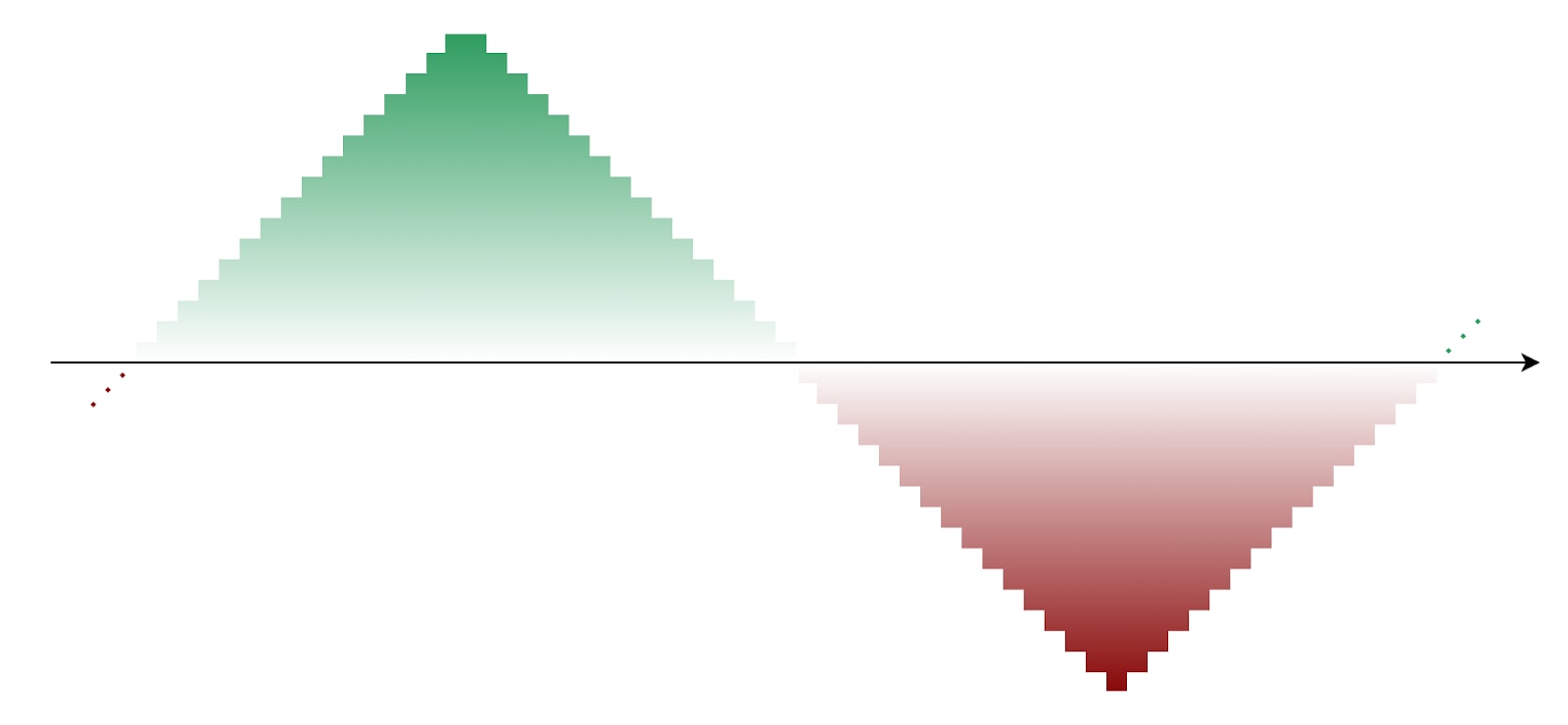

In particular, symmetric classical utilitarianism implies interchangeability between a non-suffering ε-life and the rollercoaster life illustrated in Figure 4.2, provided that the “overall welfare” of the rollercoaster life equals ε.

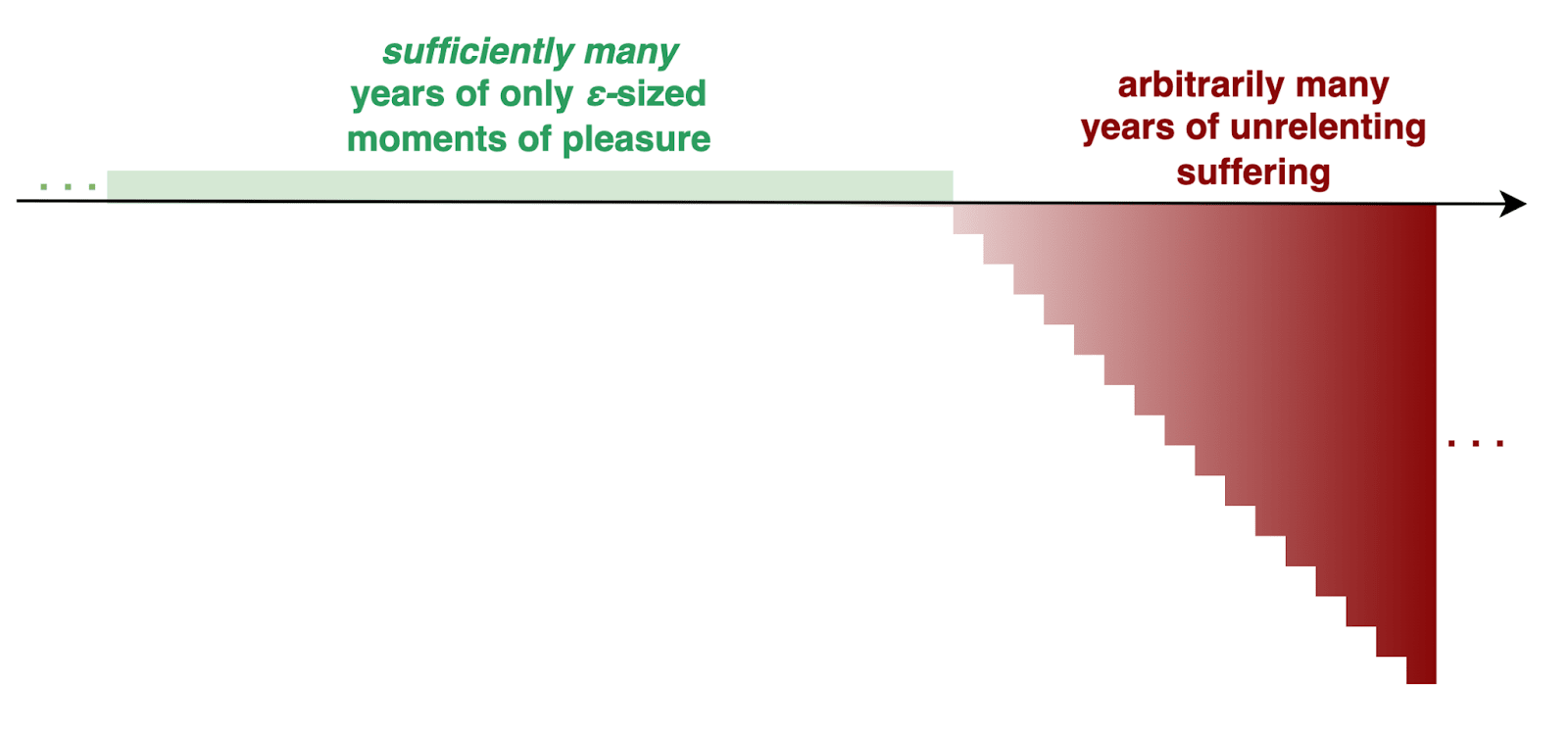

Moreover, many offsetting views, including symmetric classical utilitarianism, would allow replacing each non-suffering ε-life in the original VRC with an “intrapersonal VRC life” (Figure 4.3).

Recently, Budolfson and Spears (2018) have argued that all plausible views in population ethics imply similarly repugnant conclusions, namely that they imply either the VRC or a closely analogous Extended VRC (XVRC), which I illustrate shortly at the beginning of 4.2.1.

The purpose of this chapter is to argue that this claim does not apply to minimalist views. In a nutshell: minimalist views avoid the VRC, can avoid repugnant XVRCs, and, at any rate, face XVRCs that are less repugnant than are the comparable conclusions faced by offsetting views.

Three claims

Budolfson and Spears make the following three claims:[3]

Claim 1: No leading welfarist axiology can avoid the VRC.

Claim 2: No other welfarist axiology in the literature can avoid the XVRC.[4]

Claim 3: The XVRC is just as repugnant as the VRC.

The authors conclude that:

Repugnant implications are an inevitable feature of any plausible axiology. If repugnance cannot be avoided, then it should not be. We believe this should be among the guiding insights for the next generation of work in value theory.

Below are my brief, initial responses to each of those three claims, and a brief overview of the rest of my response.

Claim 1 does not apply to minimalist axiologies

The scope of Claim 1 (“No leading welfarist axiology can avoid the VRC”) is limited to ‘leading’ welfarist axiologies, namely to views that, according to the authors, are commonly-held in the axiological literature.[5]

Thus, the scope of Claim 1 does not cover minimalist axiologies, although axiologies that are essentially minimalist have been defended in the philosophical literature.[6]

To the extent that the VRC seems repugnant, it is worth noting that all minimalist axiologies do avoid the VRC (cf. 3.3.3), and can do so on a principled basis without relying on arbitrary or ad hoc assumptions.

Claim 2 requires that we extend the XVRC

Claim 2 (“No other welfarist axiology in the literature can avoid the XVRC”) is not straightforward to evaluate, because the original XVRC, as the authors define it, applies strictly only to views that make the assumption of independently aggregable positive utility.[7]

This assumption is not made by minimalist welfarist axiologies, such as antifrustrationism, tranquilism, and some types of negative utilitarianism.[8]

Yet we can slightly extend the original definition of the XVRC, and thereby construct XVRCs for minimalist views. This is done in 4.2.

Claim 3 requires comparisons

Finally, we will evaluate Claim 3 (“The XVRC is just as repugnant as the VRC”) in the case of minimalist views. If Claim 3 were true not only for offsetting views but also for minimalist views, that would support the authors’ conclusion that repugnant implications are inevitable.

Yet is it true? That is, are minimalist XVRCs just as repugnant as the VRC?

Settling this question requires that we directly compare minimalist XVRCs against the VRC.

Chapter overview

Section 4.2 illustrates comparable XVRCs for offsetting and minimalist views.

The illustrations are divided into three separate categories, based on the underlying assumptions about aggregation:

- Archimedean views (“Quantity Can Always Substitute for Quality”) (4.2.1),

- lexical views with sharp thresholds (4.2.2.1), and

- lexical views without sharp thresholds (4.2.2.2).

Section 4.3 unpacks which sources of repugnance are present in the different XVRCs, and why I exclude the element of non-creation as non-repugnant.

Section 4.4 evaluates the comparative repugnance of the offsetting and minimalist XVRCs within each of the three categories of views.[9] Additionally, it explains how at least some minimalist views only face XVRCs that are less repugnant than the original VRC, which implies that Claim 3 (“The XVRC is just as repugnant as the VRC”) does not hold for those minimalist views.

2. Comparable XVRCs for offsetting and minimalist views

Archimedean views (“Quantity can always substitute for quality”)

Let us look at comparable XVRCs for Archimedean views. (Archimedean views roughly say that “quantity can always substitute for quality”, such that, for example, a sufficient number of minor pains can always be added up to be worse than a single instance of extreme pain.[10])

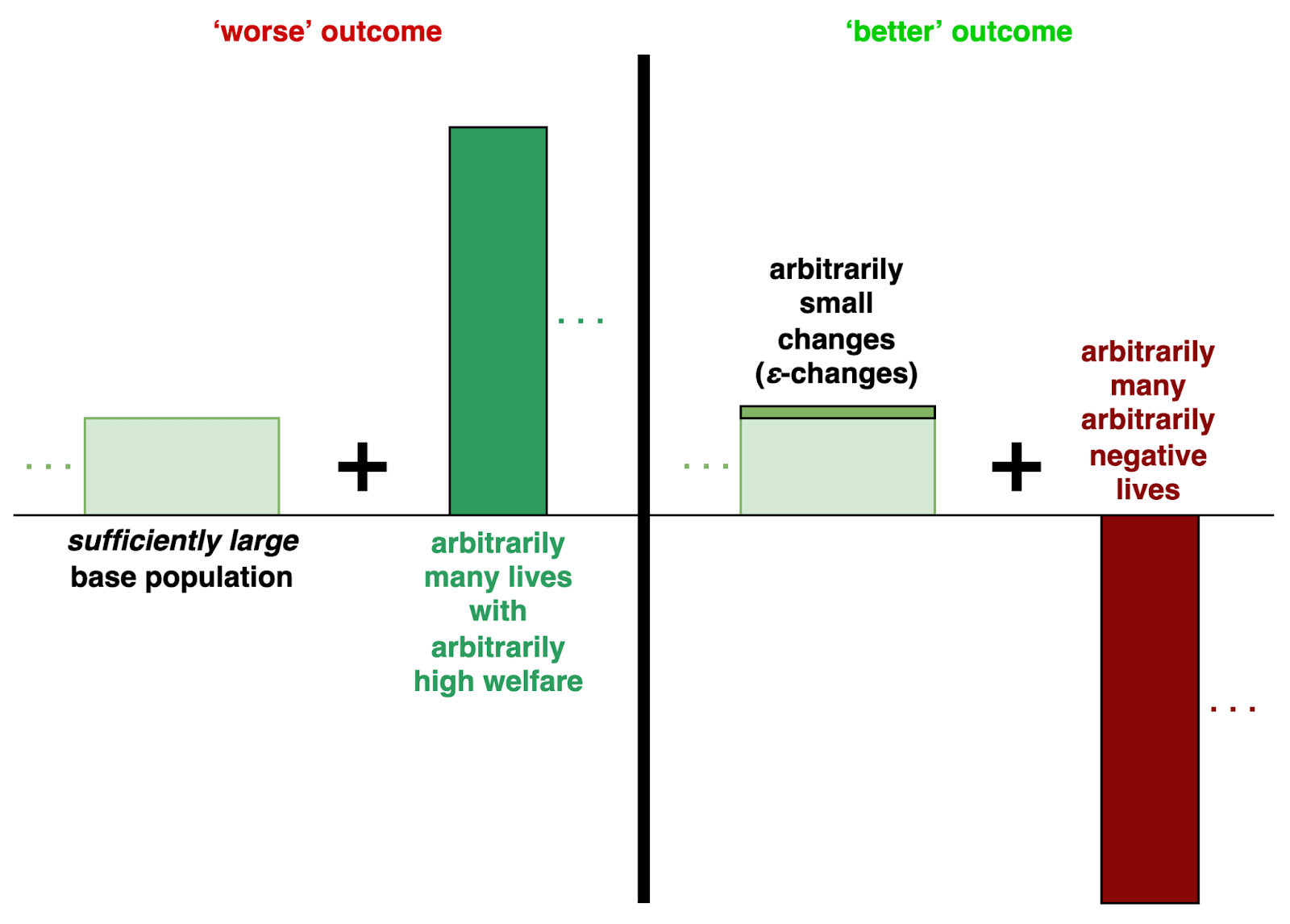

Figure 4.4 illustrates the original XVRC for Archimedean offsetting views, which goes roughly like this:[11]

| Rather than adding arbitrarily many lives with arbitrarily high welfare, it is better to add arbitrarily many arbitrarily negative lives and have each life in a sufficiently large base population receive an arbitrarily small quantity (ε) of positive welfare (an ε-change). |

A special case of the Archimedean offsetting XVRC is “Creating hell to please the blissful” (Figure 4.5), in which every life in the base population is brought from a very high welfare to an even higher welfare at the cost of adding maximally bad lives.[12]

In the case of minimalist welfarist axiologies, ‘welfare’ cannot refer to independently aggregable positive utility. Instead, minimalist views construe welfare as the absence of intrinsically problematic features, such as ‘frustration’, ‘craving’, or ‘discontentment’.[13]

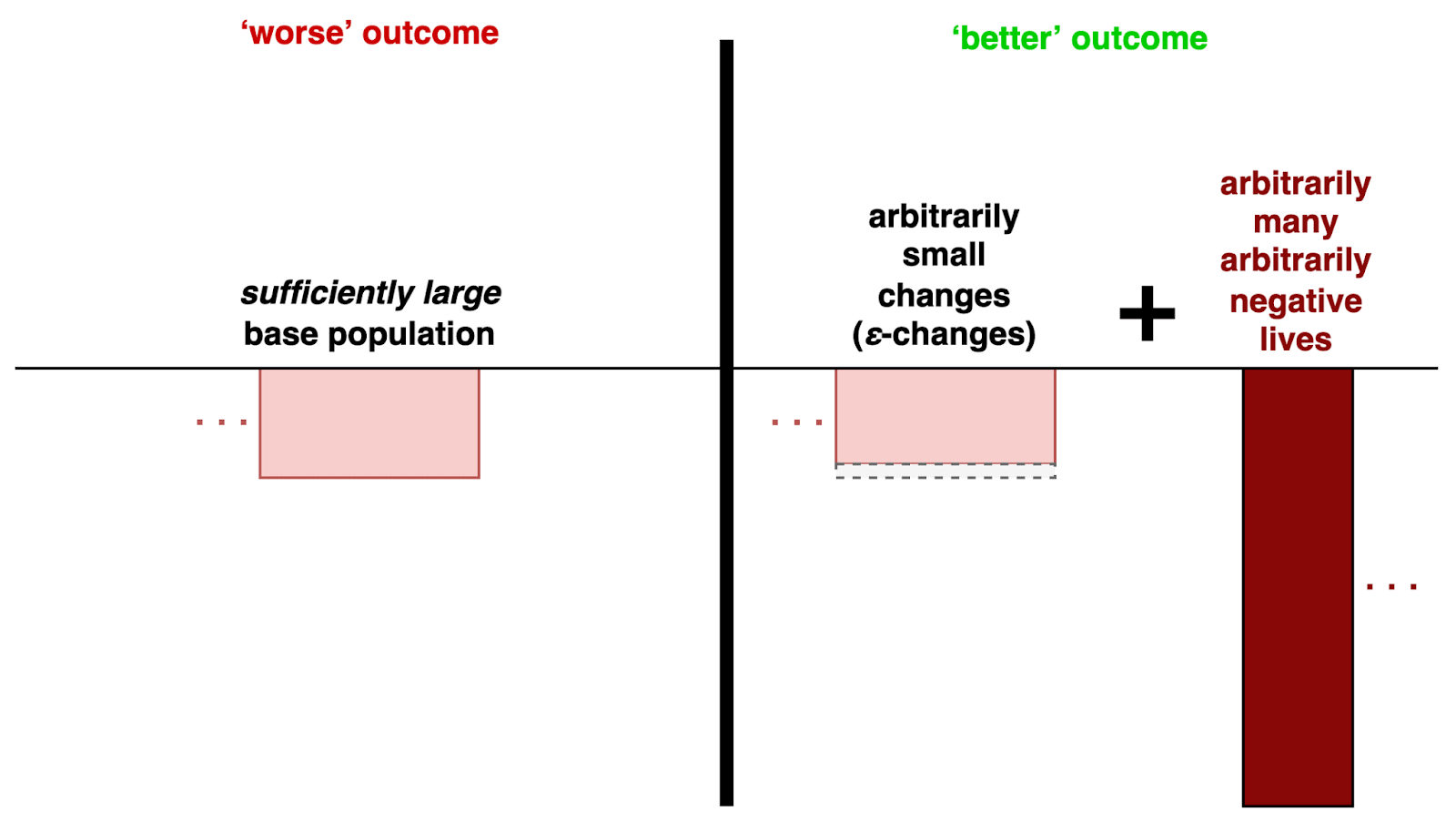

Yet we can nonetheless construct an XVRC for Archimedean minimalist views by defining the arbitrarily small changes (ε-changes) more generally as ε-sized improvements in welfare.

Thus, an Archimedean minimalist XVRC could go like this (Figure 4.6):

| It is a net improvement to add arbitrarily many arbitrarily negative lives so as to barely reduce the suffering of each life in a sufficiently large base population.[14] |

Another XVRC for Archimedean minimalist views is illustrated in Figure 4.7, which is basically what is known as the Reverse Repugnant Conclusion.[15]

![Figure 7. Another XVRC for Archimedean minimalist views (the Reverse Repugnant Conclusion). [7]](https://res.cloudinary.com/cea/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto/v1/mirroredImages/FEJLFr5ef82FSY8vr/cjfbrez31v0h4nauoc3o)

Lexical views (“Some qualities get categorical priority”)

Let us now look at comparable XVRCs within a prominent class of non-Archimedean views, namely what are known as lexical views. Lexical views deny that “quantity can always substitute for quality”; instead, they assign categorical priority to some qualities relative to others.[16]

Specifically, lexical minimalist views entail lexicality between bads, such as by (all else equal) prioritizing the reduction of unbearable suffering over any mild discomfort.[17] Additionally, lexical offsetting views entail lexicality between goods (e.g. higher pleasures over lower pleasures), or between goods and bads (e.g. higher pleasures over mild discomfort).[18]

Do lexical views face XVRCs? Notably, lexical views may question the assumption of representing welfare with a single real number to begin with.[19] Thus, lexical views may reject the formal framework of the Archimedean XVRC, whose definition entails arbitrarily small changes (ε-changes) to the aggregate welfare (a real number) of each life in the base population.

However, even if we reject the Archimedean framework, we can still reinterpret the XVRC to construct analogous lexical XVRCs (for both minimalist and offsetting lexical views).

Let us first look at such XVRCs for lexical views with sharp thresholds, and then for lexical views without sharp thresholds.

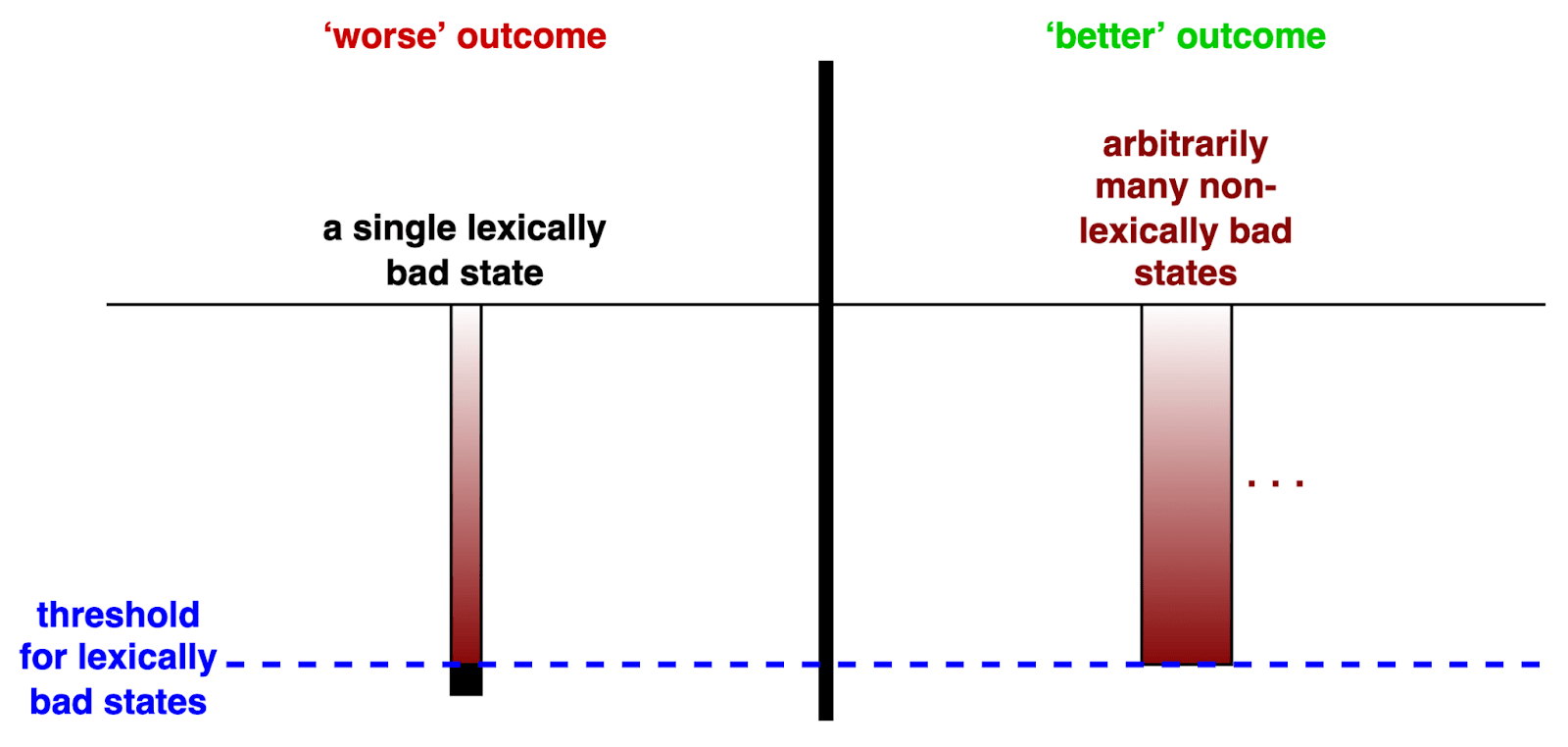

With sharp thresholds

Consider a lexical minimalist view with a sharp threshold. For instance, one may hold that some sentient minds have a sharp breaking point at which suffering becomes unbearable, and that the passing of this point is categorically worth avoiding more than any amount of “bending without breaking”.[20]

Figure 4.8 illustrates an XVRC for such a view:

| It is a net improvement to add arbitrarily many non-lexically bad states (of e.g. barely bearable suffering) as long as we reduce the number of lexically bad states (of e.g. unbearable suffering). |

A comparable lexical offsetting view might entail all of the following claims:

- There is a lexical threshold between some goods (e.g. higher and lower pleasures).

- There is a lexical threshold between some bads (e.g. bearable and unbearable suffering).

- No amount of non-lexical goods (e.g. lower pleasures) can counterbalance a lexically bad state.

- Some amount of lexical goods (e.g. higher pleasures) can counterbalance a lexically bad state.

Figure 4.9 illustrates an XVRC for such a view:

| It is a net improvement to add arbitrarily many arbitrarily negative lives (that entail lexically bad states) so as to replace, within each life in a sufficiently large base population, a just barely not lexically good state with a lexically good state.[21] |

![Figure 9. An XVRC for lexical offsetting views with sharp thresholds. [11]](https://res.cloudinary.com/cea/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto/v1/mirroredImages/FEJLFr5ef82FSY8vr/wy2wn0oggnemhiyzursj)

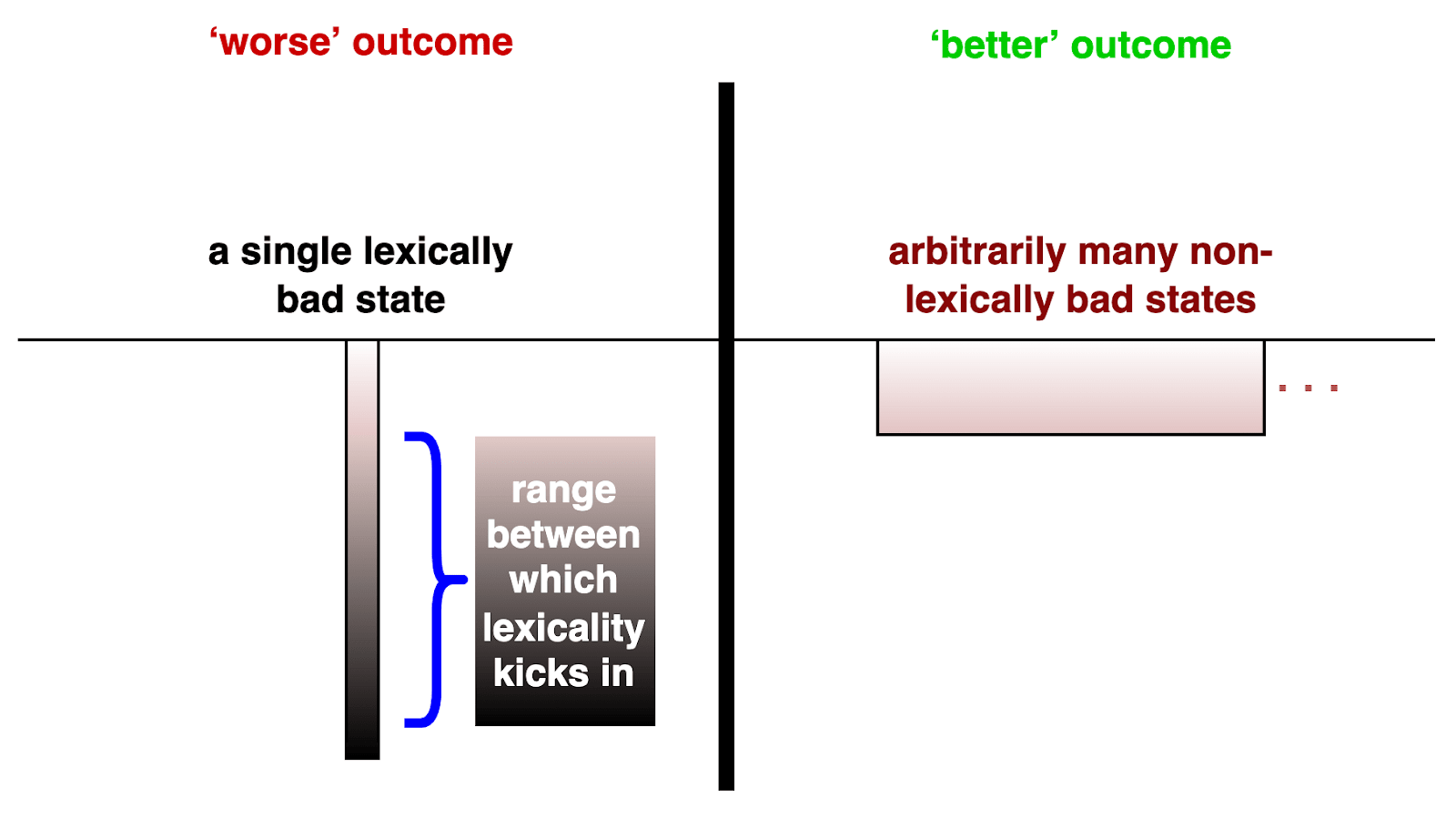

Without sharp thresholds

Finally, it has been argued that lexical views need not entail sharp thresholds like the ones that were abstractly sketched in the previous subsection. After all, perhaps a more plausible lexical view would hold that (e.g.) unbearableness comes in degrees.[22]

A “non-sharp” lexical threshold could be a range (e.g. in the intensity of suffering) between which the suffering becomes lexically worse than suffering above the range. This would imply that no duration of suffering above the range (e.g. “wholly bearable suffering”) can be worse than a single instance of suffering below the range (e.g. “wholly unbearable suffering”).[23]

Figure 4.10 illustrates a non-sharp lexical minimalist XVRC:

| It is a net improvement to add arbitrarily many non-lexically bad states (e.g. wholly bearable suffering) as long as we reduce the number of lexically bad states (e.g. wholly unbearable suffering). |

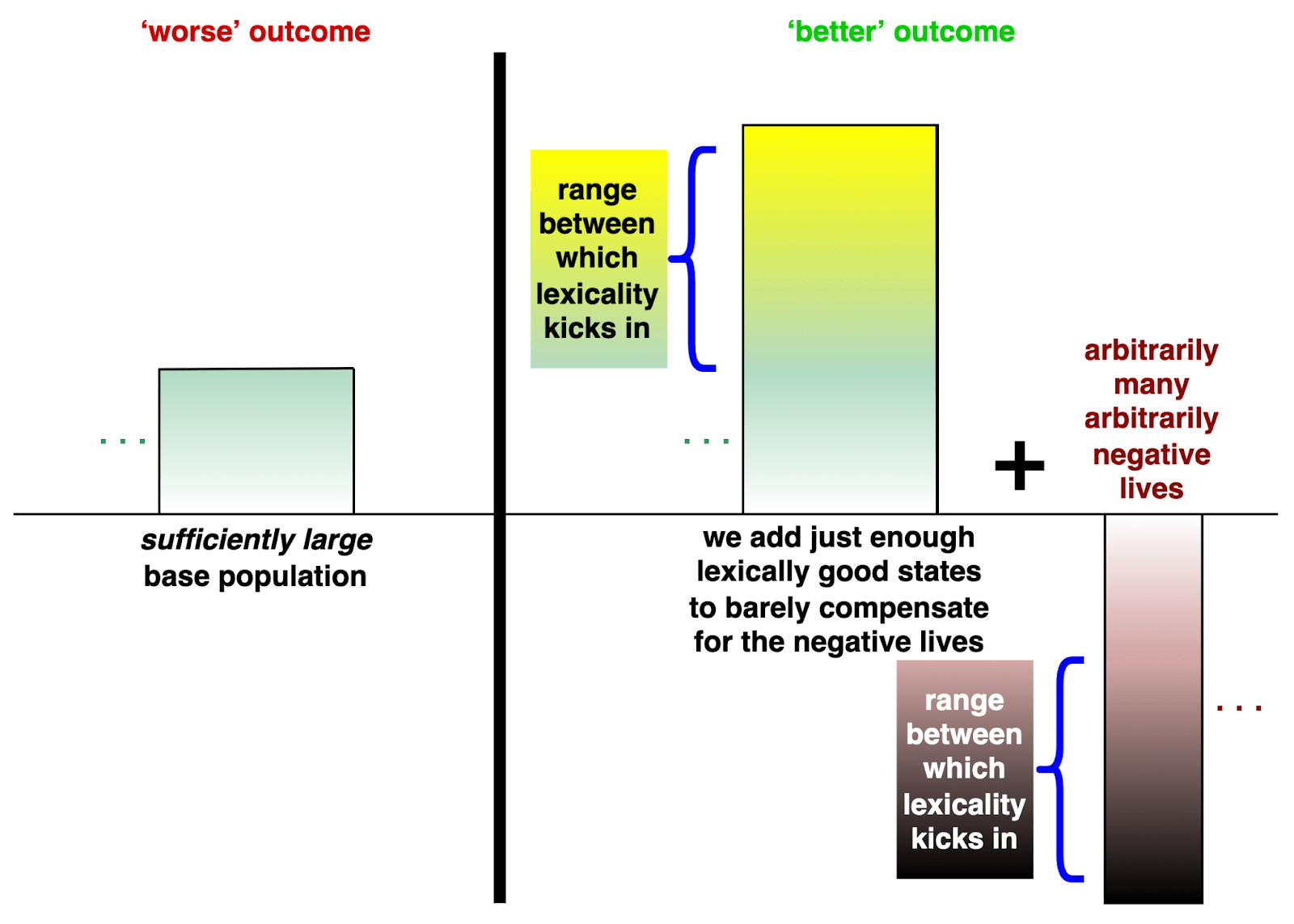

Figure 4.11 illustrates a non-sharp lexical offsetting XVRC (based on the same four assumptions that were made for the previous offsetting view).

| It is a net improvement to add an arbitrarily large number of arbitrarily negative lives (that entail lexically bad states) so as to add one lexically good state to each life in a sufficiently large base population. |

3. Sources of repugnance

Section 4.4 will evaluate the comparative repugnance of the above XVRCs and the original VRC. Before that, let us unpack which sources of repugnance are present in the different XVRCs.

Creating non-relieving goods for some at the price of unbearable suffering for others

Only the offsetting XVRCs entail the creation of non-relieving goods for some at the price of unbearable suffering for others.

By contrast, the changes in the minimalist XVRCs seem qualitatively less frivolous, because they are about the reduction of suffering rather than about the increase of non-relieving pleasure — pleasure that has no positive roles for relieving anyone’s burden.[24]

Enabling rollercoaster lives that all contain unbearable suffering

Only offsetting views allow replacing the lives in the various XVRCs with “rollercoaster lives” that all contain unbearable suffering (Figure 4.2). Moreover, Archimedean offsetting views allow replacing them with “intrapersonal VRC lives” (Figure 4.3). In principle, each of these “rollercoaster lives” and “intrapersonal VRC lives” could contain arbitrarily many instances of extreme suffering.

By contrast, minimalist views reject the offsetting (‘good minus bad’) view of aggregation that enables the rollercoaster interpretation in the first place. Thus, minimalist views entail only the non-rollercoaster versions of the minimalist XVRCs above, whereas the offsetting views entail those same conclusions plus their rollercoaster versions.

Making seemingly trivial changes at the price of unbearable suffering

Budolfson and Spears (2018) seem to attribute repugnance in large part to the unbounded aggregation of arbitrarily tiny changes.[25]

Such aggregation is indeed a potential source of repugnance in at least the Archimedean XVRCs, for both offsetting and minimalist views.

Additionally, perhaps an “atom” of a lexical offsetting good — such as the briefest possible experience of a non-relieving higher pleasure (the authors mention a tiny duration of Mozart) — is intuitively still roughly as trivial as is any other instance of a non-relieving good.

However, one could reasonably argue that the following XVRC statements, made by Budolfson and Spears in the quotes below, do not apply in the case of lexical minimalist axiologies:

Either something that seems important will be outweighed by an unbounded number of initially unimportant-seeming matters, something that initially seems unimportant will unduly shape the outcome, or both. (pp. 30–31)

This statement does not seem to hold for lexical minimalist views. After all, they would not allow “something that seems important” (such as extreme suffering) to be outweighed by unimportant-seeming matters, nor would they allow “something that initially seems unimportant” (such as non-relieving goods) to unduly shape the outcome. And in particular, extreme suffering seems important, even if it only lasts for a short duration.[26]

[Our argument] considers the possibility that better-off people are qualitatively different [and] that higher pleasures are qualitatively different. In general, because lexical views still must aggregate across people, they remain subject to repugnance. (p. 34)

As noted, perhaps repugnant implications are inevitable for offsetting views even in their lexical versions (cf. adding tiny durations of non-relieving lexical goods at the price of unbearable suffering).

Yet the authors do not seem to discuss lexical views that give overriding priority to the prevention of extreme bads. Such views are arguably uniquely resistant to this “trivial changes” source of repugnance.[27]

Non-creation?

The three sources of repugnance covered in the last three subsections each entail the increase of unbearable suffering for the sake of changes that seem relatively frivolous or trivial in comparison.

The original VRC and XVRC additionally entail what might seem like a fourth source of repugnance, namely the non-creation of high-welfare lives whose existence would purportedly be a great benefit for their own sake. Let us call this the “non-creation of happy isolated lives”.

A key thing to note when evaluating non-creation as a potential source of repugnance is that we need to carefully isolate our intuitions on this question — that is, on non-creation’s independent repugnance, all else equal — from the influence of various factors that are actually external to the question itself. When we have done so, I maintain that non-creation is not an independent source of repugnance.[28]

Let us briefly unpack some of the reasons why non-creation is plausibly non-repugnant:

- How repugnant is the non-creation of lives that are described as “awesome”, “flourishing”, or “full of love and accomplishment”, all else equal?[29] Such framings of the lives in question are quite common, yet they may cause our evaluation to become strongly biased in favor of creation. After all, our practical intuitions easily associate those descriptions with lives that play positive roles for others (even on purely minimalist views of value), whereas standard population axiology counterintuitively requires that we ignore all such roles.[30]

- One way to properly respect the ‘all else equal’ assumption is to explicitly highlight that the lives in question are forever causally isolated lives that never affect any other beings in any way (e.g. that they are happy isolated matrix lives, dwellers of their closed island worlds, or the like, which clearly make no difference beyond themselves). And to further remove our potentially self-related concerns from the picture, we should imagine that no one will know whether we endorsed the creation or non-creation of those happy isolated lives, and that even we will have our memory wiped of the decision immediately after we make it.[31]

- For experientialist consequentialists, the question of whether non-creation is repugnant becomes a question that arguably requires a thorough phenomenological search, namely a search for non-relieving goods that constitute a positive counterpart to suffering. Yet such a counterpart plausibly does not exist.[32]

- For preference-based views, it likewise makes sense to think of preference satisfaction as an inherently asymmetric endeavor. Singer (1980): “The creation of preferences which we then satisfy gains us nothing. We can think of the creation of the unsatisfied preferences as putting a debit in the moral ledger which satisfying them merely cancels out.”[33] Fehige (1998): “We have obligations to make preferrers satisfied, but no obligations to make satisfied preferrers. … Maximizers of preference satisfaction should instead call themselves minimizers of preference frustration.”[34]

4. Comparative repugnance

Let us now evaluate the comparative repugnance of the XVRCs and the original VRC.

Tables 4.1–4.3 show how the minimalist XVRCs explored above are a proper subset of the XVRCs that are implied by the corresponding offsetting views explored above.

Specifically, the offsetting views entail the minimalist implications, their “rollercoaster” or “intrapersonal VRC” versions,[35] and the offsetting implications.

Notably, only the offsetting implications entail all three of the sources of repugnance that were considered above (that is, creating non-relieving goods at the price of others’ suffering; rollercoaster lives; and seemingly trivial changes at the price of unbearable suffering). In contrast, at least some of the minimalist XVRCs entail none of these sources of repugnance.

For the reasons explained in the previous section, I do not count non-creation as a source of repugnance below.

Table 4.1. Implications of the Archimedean views (4.2.1).

View | Archimedean | |

|---|---|---|

| Implication | Offsetting | Minimalist |

Very Repugnant Conclusion (Fig 4.1) | x | |

rollercoaster version | x | |

intrapersonal VRC version | x | |

Archimedean offsetting XVRC (Fig 4.4) | x | |

rollercoaster version | x | |

intrapersonal VRC version | x | |

“Creating hell to please the blissful” (Fig 4.5) | x | |

rollercoaster version | x | |

intrapersonal VRC version | x | |

Archimedean minimalist XVRC (Fig 4.6) | x | x |

rollercoaster version | x | |

intrapersonal VRC version | x | |

Reverse Repugnant Conclusion (Fig 4.7) | x | x |

rollercoaster version | x | |

intrapersonal VRC version | x | |

Among the Archimedean implications, the offsetting XVRCs (Figures 4.4 and 4.5) entail more sources of repugnance than do the minimalist XVRCs (Figures 4.6 and 4.7). Specifically, the offsetting XVRCs entail all the same sources of repugnance as does the original VRC, with no redeeming “anti-repugnant” elements. We can thus agree with Budolfson and Spears’ (2018) claim that these XVRCs are just as repugnant as the VRC (i.e. Claim 3).

By contrast, the minimalist XVRCs lack the repugnance of creating non-relieving goods for some at the price of unbearable suffering for others, and the repugnance of “rollercoaster” or “intrapersonal VRC” lives that all contain unbearable suffering.

Thus, the repugnance of the minimalist XVRCs relative to the VRC depends on whether they entail any additional sources of repugnance that the VRC does not. And one may reasonably hold that they do not, which would imply that Claim 3 does not hold for Archimedean minimalist views.[36]

Table 4.2. Implications of the lexical views with sharp thresholds (4.2.2.1).

View | Lexical sharp | |

|---|---|---|

| Implication | Offsetting | Minimalist |

Lexical sharp minimalist XVRC (Fig 4.8) | x | x |

rollercoaster version | x | |

Lexical sharp offsetting XVRC (Fig 9) | x |

|

rollercoaster version | x | |

Among the sharp lexical views, the offsetting XVRC (Figure 4.9) again seems to entail all the same sources of repugnance as does the original VRC. Only the offsetting view can accept an increase in the number of lexically bad states, such as unbearable suffering. And it does so for the sake of producing non-relieving goods.

Table 4.3. Implications of the lexical views without sharp thresholds (4.2.2.2).

View | Lexical non-sharp | |

|---|---|---|

| Implication | Offsetting | Minimalist |

Lexical non-sharp minimalist XVRC (Fig 10) | x | x |

rollercoaster version | x | |

Lexical non-sharp offsetting XVRC (Fig 11) | x |

|

rollercoaster version | x | |

Finally, the non-sharp lexical minimalist XVRC (Figure 4.10) entails that no amount of sufficiently mild states of suffering can be worse than unbearable suffering.

By comparison, the corresponding offsetting view implies not only the same theoretical conclusion (Figure 4.10), but also the arbitrary increase of unbearable states for the sake of creating purportedly sufficient amounts of non-relieving higher goods (Figure 4.11). Additionally, the offsetting view again entails the rollercoaster versions that would “require everyone in the chosen population to experience [arbitrarily] terrible suffering”.[37]

Conclusions

To respond to the three claims we set out to explore:

Claim 1: No leading welfarist axiology can avoid the VRC.

Minimalist welfarist axiologies do avoid the VRC. (And they also avoid the “rollercoaster” and “intrapersonal VRC” versions of the original Repugnant Conclusion.)

Claim 2: No other welfarist axiology in the literature can avoid the XVRC.

Minimalist views do entail modified minimalist XVRCs (cf. Figures 4.6, 4.7, 4.8, and 4.10).

Claim 3: The XVRC is just as repugnant as the VRC.

This seems true for offsetting views. Yet the minimalist XVRCs are considerably less repugnant than the VRC. In particular, at least the Archimedean minimalist and the non-sharp lexical minimalist XVRCs (Figures 4.6 and 4.10) entail fewer sources of repugnance (4.3) than does the VRC, arguably with no additional, greater sources of repugnance.

Lastly, the XVRCs generated by minimalist views are consistently (4.4) less repugnant than those generated by the corresponding offsetting views. Thus, the minimalist XVRCs seem uniquely unrepugnant. This is a strong point in favor of minimalist views over offsetting views in population axiology, regardless of the specific details of one’s theory of aggregation.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for helpful comments by Anthony DiGiovanni, James Faville, Lukas Gloor, Simon Knutsson, Winston Oswald-Drummond, Michael St. Jules, and Magnus Vinding.

Special thanks to Magnus Vinding for guiding the development of this essay.

Commenting does not imply endorsement of any of my claims.

References

Anonymous. (2015). Negative Utilitarianism FAQ. utilitarianism.com/nu/nufaq.html

Breyer, D. (2015). The cessation of suffering and Buddhist axiology. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 22, 533–560. blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2015/12/Breyer-Axiology-final.pdf

Budolfson, M. & Spears, D. (2018). Why the repugnant conclusion is inescapable. Princeton University Climate Futures Initiative working paper. web.archive.org/web/20220614105405/https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/cfi/files/budolfson_spears_2018_repugnant_cfi.pdf

Carlson, E. (1998). Mere addition and two trilemmas of population ethics. Economics & Philosophy, 14(2), 283–306. doi.org/10.1017/S0266267100003862

Carlson, E. (2007). Higher Values and Non-Archimedean Additivity. Theoria, 73(1), 3–27. doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-2567.2007.tb01185.x

DiGiovanni, A. (2021b). Tranquilism Respects Individual Desires. anthonydigiovanni.substack.com/p/tranquilism-respects-individual-desires

Fehige, C. (1998). A Pareto Principle for Possible People. In C. Fehige & U. Wessels (Eds.), Preferences (pp. 508–543). Walter de Gruyter. fehige.info/pdf/A_Pareto_Principle_for_Possible_People.pdf

Fox, J. I. (2022). Does Schopenhauer accept any positive pleasures? European Journal of Philosophy. doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12830

Gloor, L. (2017). Tranquilism. longtermrisk.org/tranquilism

Knutsson, S. (2016c). Value lexicality. simonknutsson.com/value-lexicality

Knutsson, S. (2021a). Many-valued logic and sequence arguments in value theory. Synthese, 199(3), 10793–10825. doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03268-4

Knutsson, S. (2021b). The world destruction argument. Inquiry, 64(10), 1004–1023. doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2019.1658631

Knutsson, S. (2022b). Undisturbedness as the hedonic ceiling. simonknutsson.com/undisturbedness-as-the-hedonic-ceiling

Lazari-Radek, K. & Singer, P. (2017). Utilitarianism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198728795.001.0001

Leighton, J. (2023). The Tango of Ethics: Intuition, Rationality and the Prevention of Suffering. Imprint Academic. goodreads.com/book/show/61889824

Mulgan, T. (2002). The reverse repugnant conclusion. Utilitas, 14(3), 360–364. doi.org/10.1017/S0953820800003654

Nebel, J. M. (2022). Totalism without repugnance. In Ethics and Existence: The Legacy of Derek Parfit, 200–231. doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192894250.003.0009

Schopenhauer, A. (1819/2012). The World as Will and Idea (Vol. 3 of 3). Project Gutenberg. gutenberg.org/files/40868/40868-pdf.pdf

Schopenhauer, A. (1851/2004). The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism. Project Gutenberg. gutenberg.org/files/10732/10732-h/10732-h.htm

Sherman, T. (2017). Epicureanism: An Ancient Guide to Modern Wellbeing (MPhil dissertation). University of Exeter. ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/32103/ShermanT.pdf

Singer, P. (1980). Right to Life? nybooks.com/articles/1980/08/14/right-to-life

Spears, D. & Budolfson, M. (2021). Repugnant conclusions. Social Choice and Welfare, 57(3), 567–588. doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01321-2

Thomas, T. (2018). Some possibilities in population axiology. Mind, 127(507), 807–832. doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzx047

Thornley, E. (2022). A dilemma for lexical and Archimedean views in population axiology. Economics & Philosophy, 38(3), 395–415. doi.org/10.1017/S0266267121000213

Tomasik, B. (2015a). Are Happiness and Suffering Symmetric? reducing-suffering.org/happiness-suffering-symmetric

Vinding, M. (2020a). Clarifying lexical thresholds. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/clarifying-lexical-thresholds

Vinding, M. (2020b). Lexical views without abrupt breaks. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/lexical-views-without-abrupt-breaks

Vinding, M. (2020c). On purported positive goods “outweighing” suffering. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/on-purported-positive-goods-outweighing-suffering

Vinding, M. (2020d). Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications. Ratio Ethica. magnusvinding.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/suffering-focused-ethics.pdf

Vinding, M. (2021). Comparing repugnant conclusions: Response to the “near-perfect paradise vs. small hell” objection. centerforreducingsuffering.org/comparing-repugnant-conclusions

Vinding, M. (2022b). Critique of MacAskill’s “Is It Good to Make Happy People?”. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/vZ4kB8gpvkfHLfz8d

Vinding, M. (2022c). Lexicality between mild discomfort and unbearable suffering: A variety of possible views. centerforreducingsuffering.org/lexicality-a-variety-of-possible-views

Vinding, M. (2022d). Lexical priority to extreme suffering — in practice. centerforreducingsuffering.org/lexical-priority-in-practice

Vinding, M. (2022e). A phenomenological argument against a positive counterpart to suffering. centerforreducingsuffering.org/phenomenological-argument

Vinding, M. (2022f). Point-by-point critique of Ord’s “Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian”. centerforreducingsuffering.org/point-by-point-critique-of-why-im-not-a-negative-utilitarian

Vinding, M. (2022i). Reply to the scope neglect objection against value lexicality. centerforreducingsuffering.org/reply-to-the-scope-neglect-objection-against-value-lexicality

Vinding, M. (2022k). A thought experiment that questions the moral importance of creating happy lives. centerforreducingsuffering.org/a-thought-experiment-that-questions-the-moral-importance-of-creating-happy-lives

Wolf, C. (1996). Social Choice and Normative Population Theory: A Person Affecting Solution to Parfit’s Mere Addition Paradox. Philosophical Studies, 81, 263–282. doi.org/10.1007/bf00372786

Wolf, C. (1997). Person-Affecting Utilitarianism and Population Policy. In J. Heller & N. Fotion (Eds.), Contingent Future Persons. Kluwer Academic Publishers. web.archive.org/web/20190410204154/https://jwcwolf.public.iastate.edu/Papers/JUPE.HTM

Wolf, C. (2004). O Repugnance, Where Is Thy Sting? In T. Tännsjö & J. Ryberg (Eds.), The Repugnant Conclusion. Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-2473-3_5

Yudkowsky, E. (2007). Torture vs. Dust Specks. lesswrong.com/posts/3wYTFWY3LKQCnAptN

Zuber, S. et al. (2021) What should we agree on about the repugnant conclusion? Utilitas, 33(4), 379–383. doi.org/10.1017/S095382082100011X

Appendix: Rollercoaster lives and the Extended Very Repugnant Conclusion (XVRC)

[This section is entirely quoted from Budolfson and Spears, 2018, pp. 18–19, only annotated with some square brackets by me.]

Let us define an ε-change as a change that makes a difference in either one of these two ways:

- ε-change: Let ε > 0 represent any small, positive quantity of well-being. An ε-change either:

- increases the well-being of one person by ε, or

- adds one new life of well-being ε.

One or more ε-changes can be part of an overall package of changes to a population, but to qualify as an ε-change, a change must be the only change that a particular person receives.

For example, an ε increase could involve slightly improving a tiny headache. One way to see that [an] ε increase could be very repugnant [on offsetting views] is to recall Portmore’s [1999] suggestion that ε lives in the restricted RC [Repugnant Conclusion] could be “roller coaster” lives, in which there is much that is wonderful, but also much [terrible] suffering, such that the good ever-so-slightly outweighs the bad [according to offsetting views]. Here, one admitted possibility is that an ε-change could substantially increase the terrible suffering in a life, and also increase good components; such [an] ε-change is not the only possible ε-change, but it would have the consequence of increasing the total amount of suffering.

With this definition of ε-change in hand, we can now characterize the

- Extended very repugnant conclusion (XVRC): For any:

- Arbitrarily large number of arbitrarily high utility people: nh > 0, uh > 0,

- Arbitrarily large number of arbitrarily negative utility people: nl ≥ 0, ul < 0, and

- Arbitrarily small positive quantity of well-being: ε > 0,

- There exists:

- A number of ε-changes: nε, and

- A (possibly empty) set of base population lives,

- such that it is better to both add to the base population the negative-utility lives and cause nε ε-changes than to add the high-utility lives.

The XVRC extension from the VRC retains all of the repugnance of choosing many terrible lives over many wonderful lives for merely ε-benefits to other people. Moreover, if ε-changes are of the “roller coaster” form [which would be ruled out by minimalist views], they could increase deep suffering considerably beyond even the arbitrarily many [u < 0] lives, and in fact could require everyone in the chosen population to experience terrible suffering.

Notes

- ^

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epsilon: “In mathematics (particularly calculus), an infinitesimally small positive quantity is commonly denoted ε.”

- ^

For more on rollercoaster lives, see Appendix 4.

- ^

- ^

For an exact definition of the XVRC, see Appendix 4. (For the main text, I will use more intuitive and less formalized descriptions of the XVRC, including some extended variants of the XVRC.)

- ^

Budolfson & Spears, 2018, p. 8.

- ^

- ^

Cf. Appendix 4.

- ^

- ^

In this chapter, I do not focus on the relative plausibility of different views across the three categories of views on aggregation, because my main focus is on the relative plausibility of offsetting versus minimalist views in general, regardless of one’s theory of aggregation.

- ^

Thornley, 2022.

- ^

Cf. Budolfson & Spears, 2018, p. 19.

- ^

From Vinding, 2021, sec. 3.

- ^

- ^

Thanks to Michael St. Jules for pointing out what can be seen as XVRCs for minimalist views.

- ^

- ^

For an introduction to value lexicality, see Knutsson, 2016c.

“Lexicographic preferences” seem named after the logic of alphabetical ordering, in which the “value entities” with top priority are prioritized first regardless of how many others there are in the “queue”; cf. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexicographic_preferences#Etymology. - ^

Knutsson, 2016c, “Lexicality between bads”. Cf. Vinding, 2022c.

- ^

Knutsson, 2016c, “Lexicality between goods”. A formalism of “higher values” over “lower values” is considered in, for instance, Carlson, 2007; Thomas, 2018; Nebel, 2022.

- ^

Vinding, 2022c, sec. 4.

- ^

More concretely, the breaking point may be equated with a supposed point at which the suffering becomes “unconsentable” (cf. Tomasik, 2015a, “Consent-based negative utilitarianism?”). For purely minimalist views, one could imagine that this corresponds to suffering so bad that an altruistic agent cannot consent to it even for preventing similar suffering for others. See also Leighton, 2023, chap. 7, “Unbearable Suffering as an Ethical Tipping Point”.

- ^

A way to make each of these lexical XVRCs entail the “arbitrarily small difference” (ε) element of the original XVRC is to make them probabilistic, so that the lexically bad state in Figure 4.8, and the lexically good states in Figure 4.9, would happen only with probability ε (cf. Budolfson & Spears, 2018, pp. 12–14).

- ^

- ^

At the same time, inter-intensity comparisons that take place entirely within this range could follow some Archimedean theory of aggregation. Note also that the “non-sharp” lexical XVRCs below are illustrated using only a single range, yet such views could just as well entail multiple different ranges (Vinding, 2022c, sec. 2). (Many interesting details about lexical views are best set aside here, because they apply to both minimalist and offsetting views, and hence those details have limited relevance for my goal of comparing these two classes of views.)

- ^

- ^

Budolfson and Spears (2018): “We note that a common theme emerges, which is that any axiology that aggregates over unbounded spaces will have repugnant implications. This is the fundamental mechanism that our proofs exploit.” (p. 2) “Because all plausible axiologies permit aggregation over unbounded spaces, this means that all plausible axiologies are exposed to repugnant conclusions” (p. 30).

- ^

Vinding, 2020d, sec. 8.12.

- ^

It seems plausible to prioritize the reduction of certainly unbearable suffering over certainly bearable suffering (and over the creation of non-relieving goods) in theory. Additionally, such a priority is, at the practical level, quite compatible with an intuitive, continuous view of the expected amount of unbearable suffering that our decisions may influence — a view that takes into account our uncertainty regarding when and where unbearable suffering might occur (Vinding, 2022d, sec. 2.2; 2022i, sec. 4).

- ^

- ^

Compare, for instance, Vinding, 2022b, “full of love and accomplishment”.

- ^

Additionally, our evaluation may be affected by factors such as what we ourselves would like to witness in the world (such as some kinds of inspiring, beautiful, or epic lives), or by us feeling that even a theoretical acceptance of non-creation would have some undesirable implications for our lives. These, too, are subtle ways of breaking the ‘all else equal’ assumption, because our evaluation of the prospective lives (for their own sake) should be unaffected by the positive roles that the creation or existence of those lives could have for others, including for us (5.2.4).

- ^

If the choice starts to feel different when we exclude these factors, this may suggest that the initial framings did indeed evoke factors whose influence was supposed to be ruled out. And this would not be surprising, as our practical intuitions are arguably not adapted to track only the subjective contents of lives, but also (and perhaps even mostly) their overall effects on others. Notably, even the standard question of whether it is “good to create happy people” may still cause a bias in favor of creation, because it may strongly evoke the relational value that these happy, intuitively prosocial people would contribute via being good friends, partners, caregivers, citizens, etc. — value whose mental exclusion may be “easier thought than done” (cf. Chapter 3).

- ^

Cf. Chapter 1; Gloor, 2017, sec. 2.1; Sherman, 2017, pp. 103–107. A key point here is to not confuse better states with intrinsically positive states, given that our seemingly positive states can be understood as merely better states along a continuum that ranges from states of unbearable torment to states in which we would be completely tranquil or undisturbed. And one may reasonably argue that “intrinsically positive states” could only be reliably identified from a (perhaps very rare) completely untroubled state to begin with (Knutsson, 2022b, sec. 5.2). Finally, we may have reasonable alternative explanations for why we might commonly believe in a positive counterpart to suffering (cf. 1.2; Vinding, 2022e, sec. 4).

- ^

- ^

See also DiGiovanni, 2021b. As with experientialist views, we need to isolate our intuitions about the supposedly independent value of preference satisfaction, ‘all else equal’, from the potentially distorting influence of our practical intuitions. This is because the satisfaction of any given preference in practice often has implications for the satisfaction of other preferences that we may intuitively care about.

- ^

Offsetting views also entail the “rollercoaster” or “intrapersonal VRC” versions of the original Repugnant Conclusion (RC) that was discussed in 3.3. While many people may think that the RC is “not necessarily unacceptable” (cf. Zuber et al., 2021), its repugnance can differ greatly depending on whether we allow the population of lives “barely worth living” to consist of rollercoaster lives (or intrapersonal VRC lives) that all contain unbearable suffering, compared to if they do not suffer at all.

- ^

Of course, one may still find the Archimedean minimalist XVRCs quite repugnant (even if less so than the VRC). Yet the remaining repugnant element of “Making seemingly trivial changes at the price of unbearable suffering” (4.3.3) is avoided by the arguably less repugnant lexical views that give priority to the reduction of lexically bad states.

- ^

Budolfson & Spears, 2018, p. 19. The quoted part suggests that the authors do not, in fact, attribute repugnance only to the “trivial changes” source of repugnance (4.3.3), but also to the additional suffering entailed by the rollercoaster lives (4.3.2). And if the arbitrary increase of unbearable states (for the sake of additional, unneeded non-relieving goods) is repugnant within lives, then it is presumably just as (if not more) repugnant between lives (4.3.1).