(Cross-posted from my website.)

Good Judgment has solicited reviews and forecasts from superforecasters regarding my report “Is power-seeking AI an existential risk,” along with forecasts on three additional questions regarding timelines to AGI, and on one regarding the probability of existential catastrophe from out-of-control AGI.

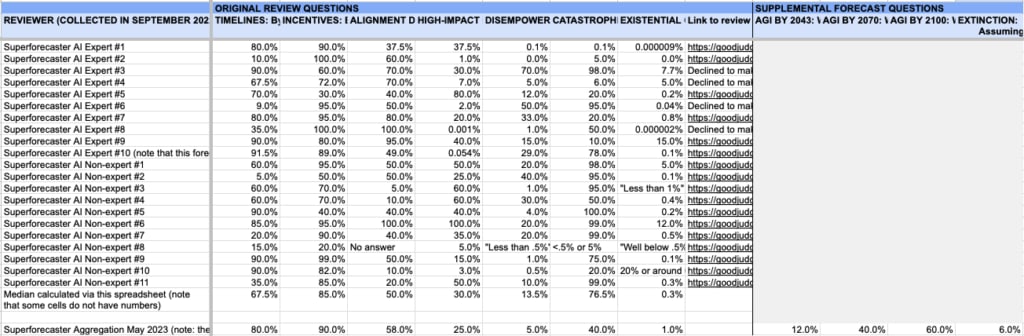

A summary of the results is available on the Good Judgment website here, as are links to the individual reviews. Good Judgment has also prepared more detailed summaries of superforecaster comments and forecasts here (re: my report) and here (re: the other timelines and X-risk questions). I’ve copied key graphics below, along with a screenshot of a public spreadsheet of the probabilities from each forecaster and a link to their individual review (where available).[1]

This project was funded by Open Philanthropy, my employer.[2] The superforecasters completed a survey very similar to the one completed by other reviewers of my report (see here for links), except with an additional question (see footnote) about the “multiple stage fallacy.”[3]

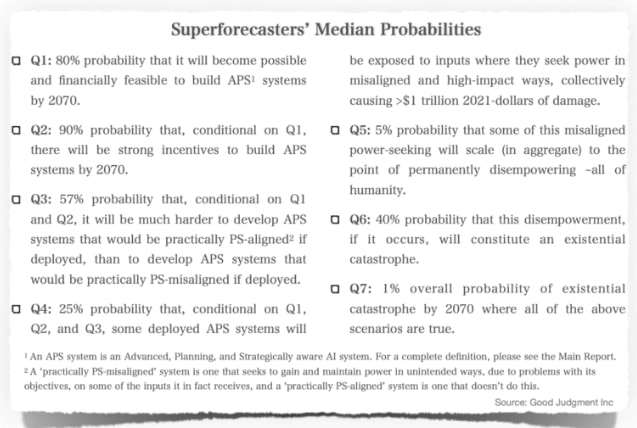

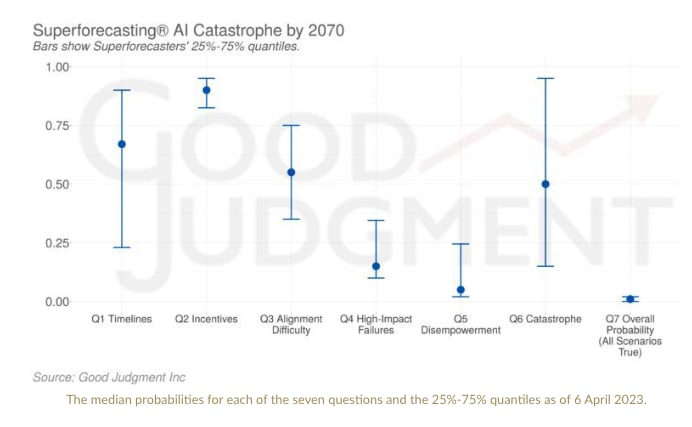

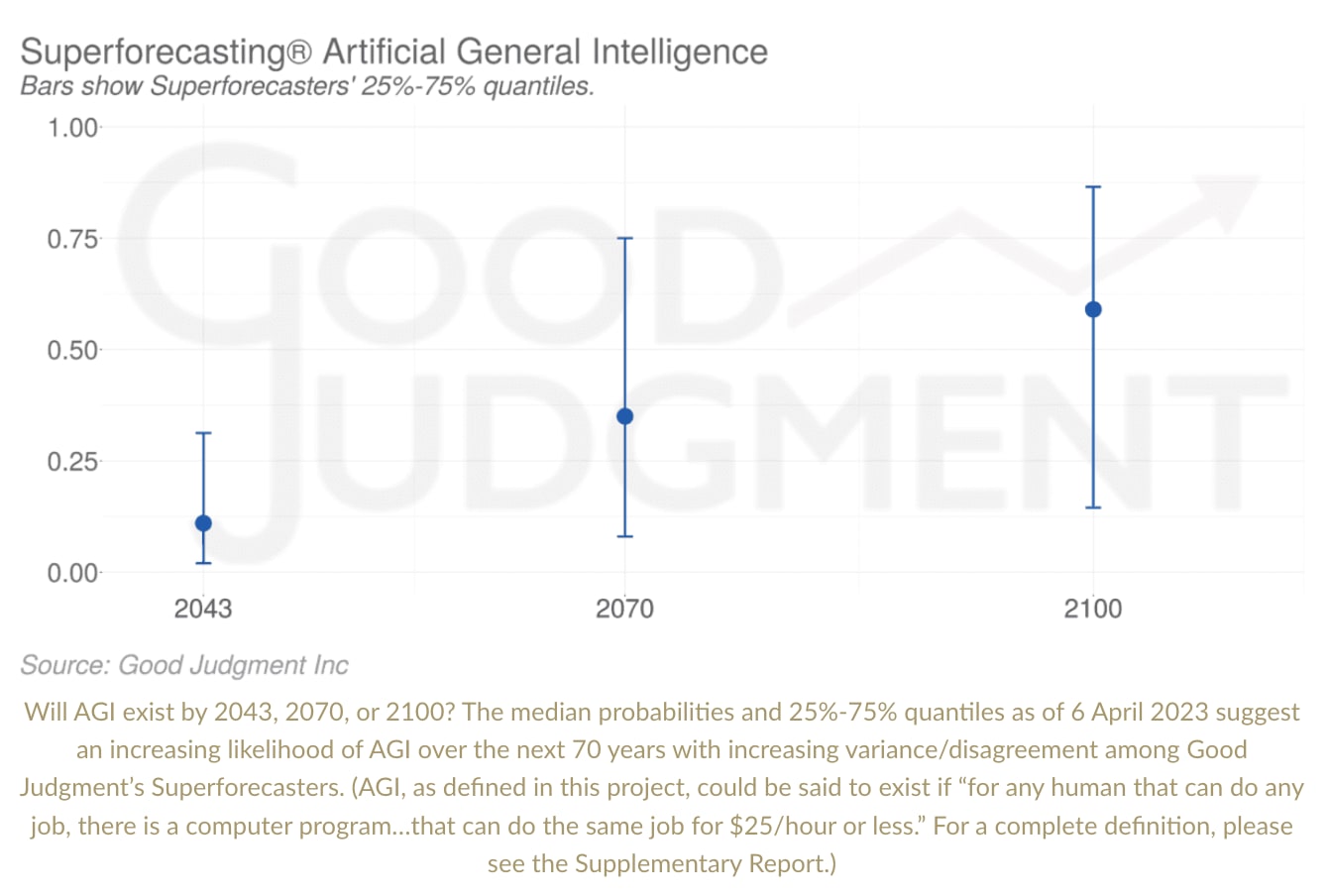

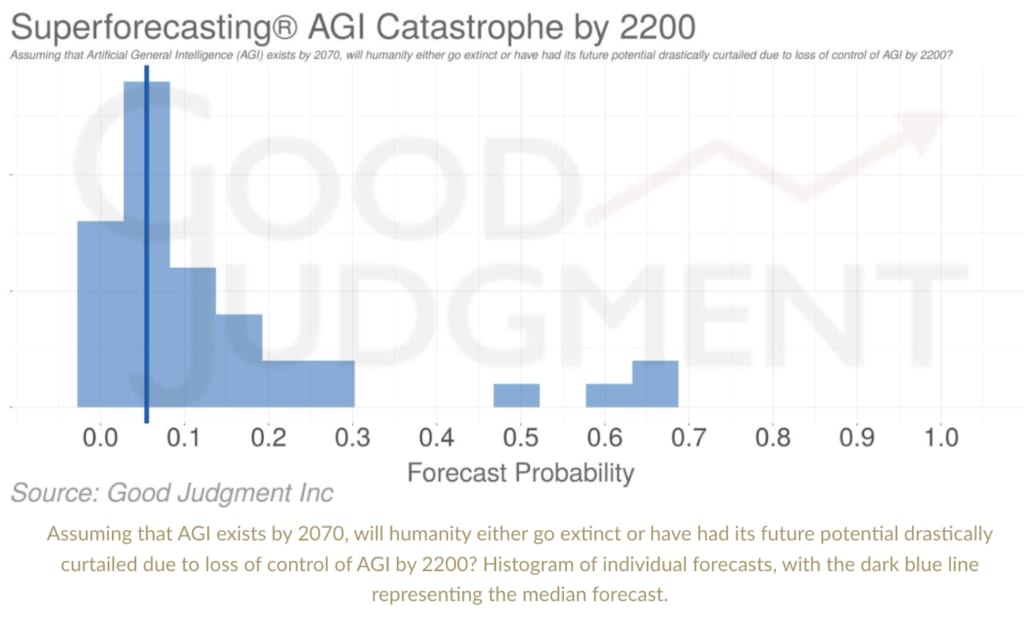

Relative to my original report, the May 2023 superforecaster aggregation places higher probabilities on the first three premises – Timelines (80% relative to my 65%), Incentives (90% relative to my 80%), and Alignment Difficulty (58% relative to my 40%) – but substantially lower probabilities on the last three premises – High-Impact Failures (25% relative to my 65%), Disempowerment (5% relative to my 40%), Catastrophe (40% relative to my 95%). And their overall probability on all the premises being true – that is, roughly, on existential catastrophe from power-seeking AI by 2070 – is 1% compared to my 5% in the original report.[4] (Though in the supplemental questions included in the second part of the project, they give a 6% probability to existential catastrophe from out-of-control AGI by 2200, conditional on AGI by 2070; and a 40% chance of AGI by 2070.[5])

To the extent the superforecasters and I disagree, especially re: the overall probability of existential risk from power-seeking AI, I haven’t updated heavily in their direction, at least thus far (though I have updated somewhat).[6] This is centrally because:

- My engagement thus far with the written arguments in the reviews (which I encourage folks to check out – see links in the spreadsheet) hasn’t moved me much.[7]

- I remain unsure how much to defer to raw superforecaster numbers (especially for longer-term questions where their track-record is less proven) absent object-level arguments I find persuasive.[8]

- I was pricing in some amount of "I think that AI risk is higher than do many other thoughtful people who've thought about it at least somewhat" already.

In this sense, perhaps, I am similar to some of the domain experts in the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament, who continued to disagree significantly with superforecasters about the probability of various extinction events even after arguing about it. However, I think it’s an interesting question how to update in the face of disagreement of this type (see e.g. Alexander here for some reflections), and I’d like to think more about it.[9]

Thanks to Good Judgment for conducting this project, and to the superforecaster reviewers for their participation. If you’re interested in more examples of superforecasters weighing in on existential risks, I encourage you to check out the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (conducted by the Forecasting Research Institute) as well.

Screenshot of spreadsheet with the probabilities from each forecaster.

- ^

After discussion with Good Judgment, I’ve made a few small adjustments, in the public spreadsheet, to the presentation of the data they originally sent to me. In particular, Superforecaster AI Expert #10 gave two different forecasts based on two different definitions of “strategic awareness,” which were distorting the median in the spreadsheet, so I have averaged them together. And the initial data listed Non-expert #8 (review here) as giving forecasts of “.01%” on various questions where I felt that the text of the review warranted different answers (namely, “No answer,” “Less than .5%”, “<.5% or 5%,” and “Well below .5%).

Note that the median in the spreadsheet differs from the “May 2023 aggregation” (and from the headline numbers on the website). This is because the individual forecaster numbers in the spreadsheet were initially produced by Superforecasters in isolation, after which point all the questions were posted on a platform where superforecasters could act as a team, challenge/question each other's views, and make more updates (plus, I’m told, other superforecasters added their judgments). The questions were then re-opened in May 2023 for a final updating round, and the May 2023 aggregation is the median of the last forecast made by everyone at that time.

- ^

It was initially instigated by the FTX Future Fund back in 2022, but Open Philanthropy took over funding after FTX collapsed.

- ^

The new question (included in the final section of the survey) was: "One concern about the estimation method in the report is that the multi-premise structure biases towards lower numbers (this is sometimes called the "multi-stage fallacy"; see also Soares here). For example, forecasters might fail to adequately condition on all of the previous premises being true and to account for their correlations, or they might be biased away from assigning suitably extreme probabilities to individual premises. When you multiply through your probabilities on the individual premises, does your estimate differ significantly from the probability you would've given to "existential catastrophe by 2070 from worlds where all of 1-6 are true" when estimating it directly? If so, in what direction?"

- ^

Note that this overall superforecaster probability differs somewhat from what you get if you just multiply through the superforecaster median for each premise. If you do that, the superforecaster numbers imply a ~10% probability that misaligned, power-seeking AI systems will cause at least a trillion dollars of damage by 2070, a ~.5% probability that they will cause full human disempowerment, and a ~.2% probability that they will cause existential catastrophe.

- ^

Technically, the 40% on AGI by 2070 and the 80% on APS-AI systems by 2070 are compatible, given that the two thresholds are defined differently. Though whether the differences warrant this large of a gap is a further question.

- ^

More specifically: partly as a result of this project, and partly as a result of other projects like the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (conducted by the Forecasting Research Institute), I now think of it as a data-point that “superforecasters as a whole generally come to lower numbers than I do on AI risk, even after engaging in some depth with the arguments.” And this, along with other sources of “outside view” evidence (for example: the evidence provided by markets, and by the expectations of academic economists, about the probability of explosive near-term growth from advanced AI), has made me somewhat more skeptical of my inside-view take. Indeed, to the extent I would’ve updated towards greater confidence in this take (or towards even higher numbers on p(doom)) had the superforecasters given higher numbers on doom, Bayesianism would mandate that I update at least somewhat downwards given that they didn’t. (Though the strength of the required update depends, also, on the probability I would’ve placed on “the superforecasters come to lower numbers than I do” vs. “the superforecasters come to similar/higher numbers than I do” prior to seeing the results. I didn’t explicitly forecast this ahead of time, but I think I would’ve viewed the former as more likely.)

- ^

The final premise -- whether permanent disempowerment of ~all humans at the hands of power-seeking AIs constitutes an existential catastrophe (the aggregated superforecaster median here is 40%) -- also strikes me as substantially a matter of philosophy/ethics rather than empirical forecasting. This makes me additionally disinclined to defer.

- ^

Though I do think that a lot of the game is in “how much weight do you give to various considerations” rather than “what considerations are in play.” The former can be harder to argue about, but it may be the place where successful forecasters have the most advantage. This is related to the more general question of how much of the signal provided by superforecasters (and especially: of an aggregated set of superforecasters) to expect to be evident in the written arguments individual forecasters offer for their numbers.

- ^

I think of it as similar to the question of how much to update on the fact that markets (and also: academic economists) generally do not seem to be expecting extreme, AI-driven economic growth with the same probability I do.

Maybe there's just nothing interesting to say (though I doubt it), but I really feel like this should be getting more attention. It's an (at least mostly, plausible some of the supers were EAs) outside check on the views of most big EA orgs about the single best thing to spend EA resources on.

Executive summary: Superforecasters' aggregated probabilities differ from the author's original report on the premises of power-seeking AI as an existential risk, with higher probabilities on some premises and lower probabilities on others.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

I think the "alignment difficulty" premise was given higher probability by superforecasters, not lower probability.