The Maternal Health Initiative (MHI) was launched through the 2022 Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Programme. Our mission is to improve the lives of women and children through a light-touch, scalable training programme on contraceptive counselling for healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa.

Six months after we started, we’re excited to share more about our work so far, our mission, and the impact we’re aiming for. This post presents a short case for the value of MHI’s work, details our goals for the rest of 2023, and explains how you can support us.

Introduction

MHI is an evidence-based non-profit dedicated to improving the lives of women and children across the world by training health workers to provide high-quality family planning counselling in the postpartum period.

We are currently conducting preliminary piloting work in northern Ghana through local partner organisations. At present, we estimate that our programming could avert a disability-adjusted life year (DALY) for $166[1], and we foresee promising pathways to significant scale.

This post provides a brief overview of the rationale for MHI’s work, what we’ve accomplished so far, where we’re heading, and how you can help. For more detailed information about our work, please visit our website, sign up to our mailing list, or reach out to us directly.

Why MHI was founded

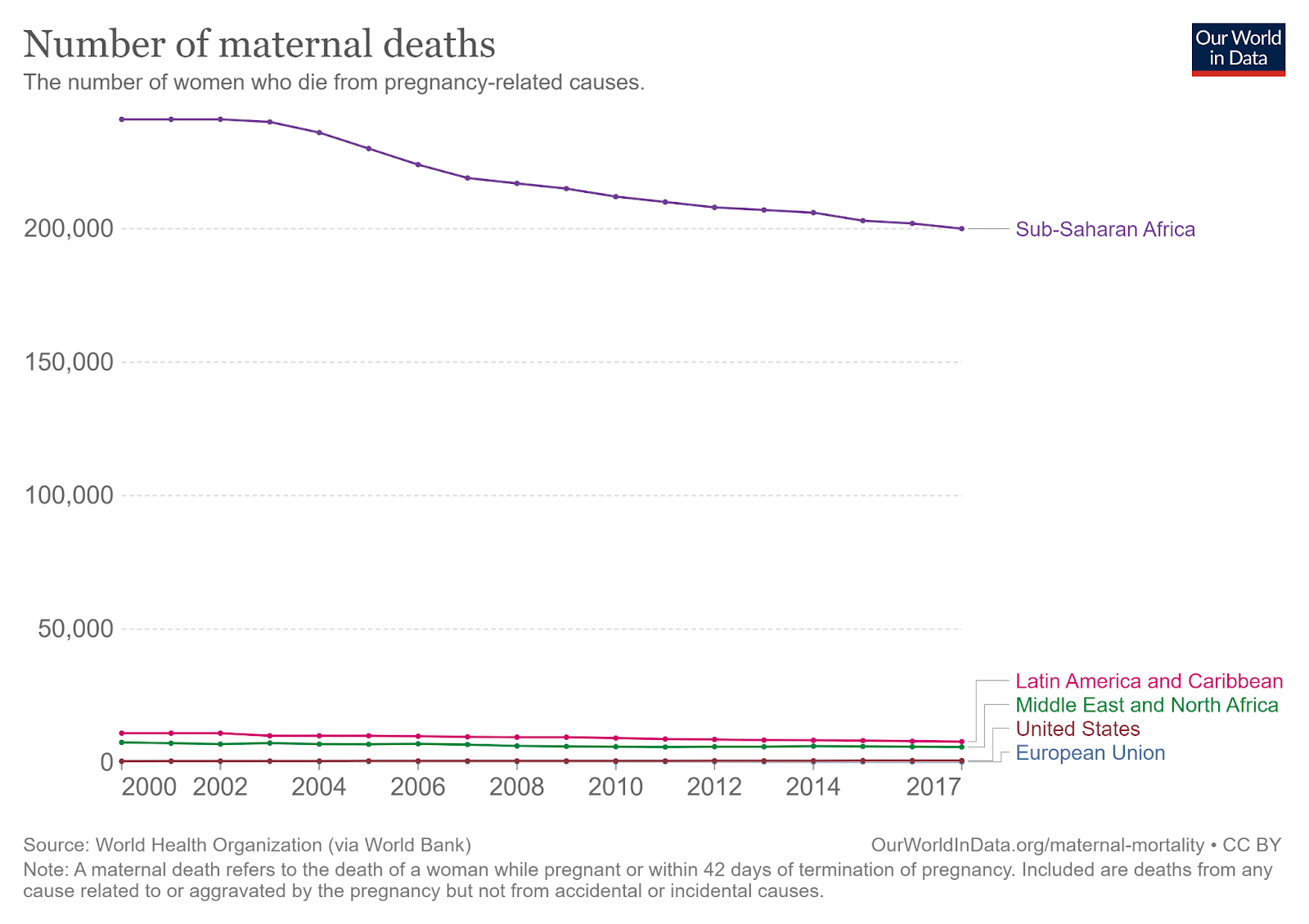

Every day, 830 women die from pregnancy-related causes[2]. These deaths overwhelmingly occur in sub-Saharan Africa, where maternal mortality rates are more than ten times higher than the next worst region. The Maternal Health Initiative was founded to change this.

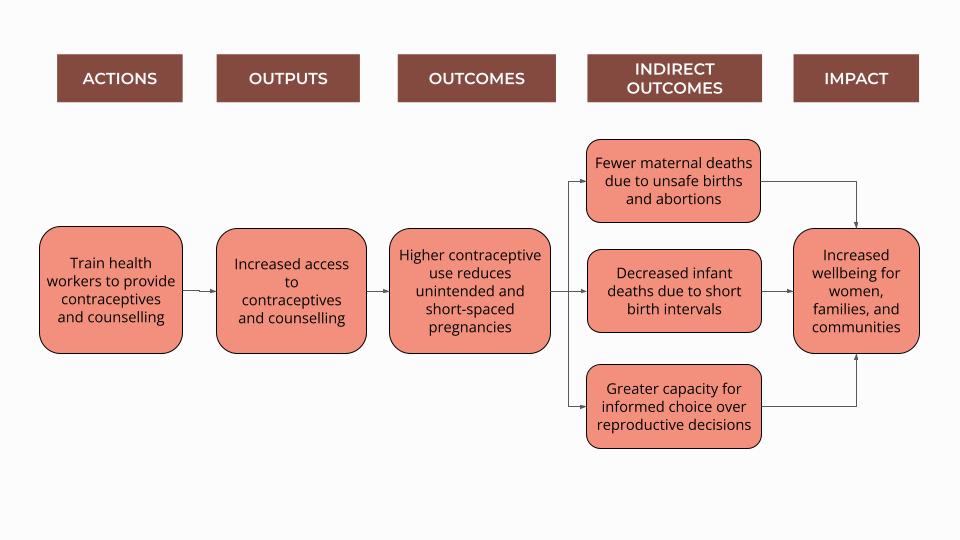

Increasing access to contraception is a tractable intervention with extensive evidence of its effectiveness in reducing maternal mortality at scale. More than this, access to family planning services can produce a wealth of additional impact, providing potentially transformative benefits to women’s autonomy, income, and wellbeing[3]. The autonomy benefits are particularly exciting: family planning appears to be one of the most cost-effective ways of improving agency.

218 million women in lower income countries have an unmet need for family planning. This resulted in more than 85 million unintended pregnancies in 2019 alone[4]. More than one third of these unintended pregnancies in sub-Saharan Africa end in an unsafe abortion[5]. These often take place outside of a health facility in countries where abortions are dangerous, heavily stigmatised, and in some cases illegal.

While there is substantial work in this space by non-EA actors, there remain significantly neglected opportunities. One of these is the specific provision of postpartum (post-birth) family planning services. Short-spaced pregnancies - births that occur within 2 years over each other - significantly increase the risks of both maternal and infant mortality.

A synthesis of the literature evaluating the impact of pregnancies that occur within 2 years of each other suggests a 18% higher risk of infant mortality and 16% higher risk of maternal mortality[6]. Despite this, contraceptive use drops to less than half of the national average in the first year after giving birth[7], with contraceptive counselling after pregnancy rarely taking place currently.

MHI is developing a programme of training to ensure high-quality contraceptive counselling consistently takes place in the postpartum period. Several randomised control trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of increased quality of care during this period[8], and we currently estimate that our program can avert a disability-adjusted life year (DALY) for just $166[1], competitive with GiveWell’s top recommended charities.

Our work

What we’ve done so far

Since September, we have undertaken a rigorous process of country and intervention evaluation. We evaluated demographic and service provision data, as well as the program locations of other major organisations, to narrow down from an initial list of more than 40 countries to two: Ghana and Sierra Leone.

We spent more than a month across January and February travelling to both countries to engage with key stakeholders, government officials, and promising partner organisations. For a longer summary of this trip, you can read this blog post.

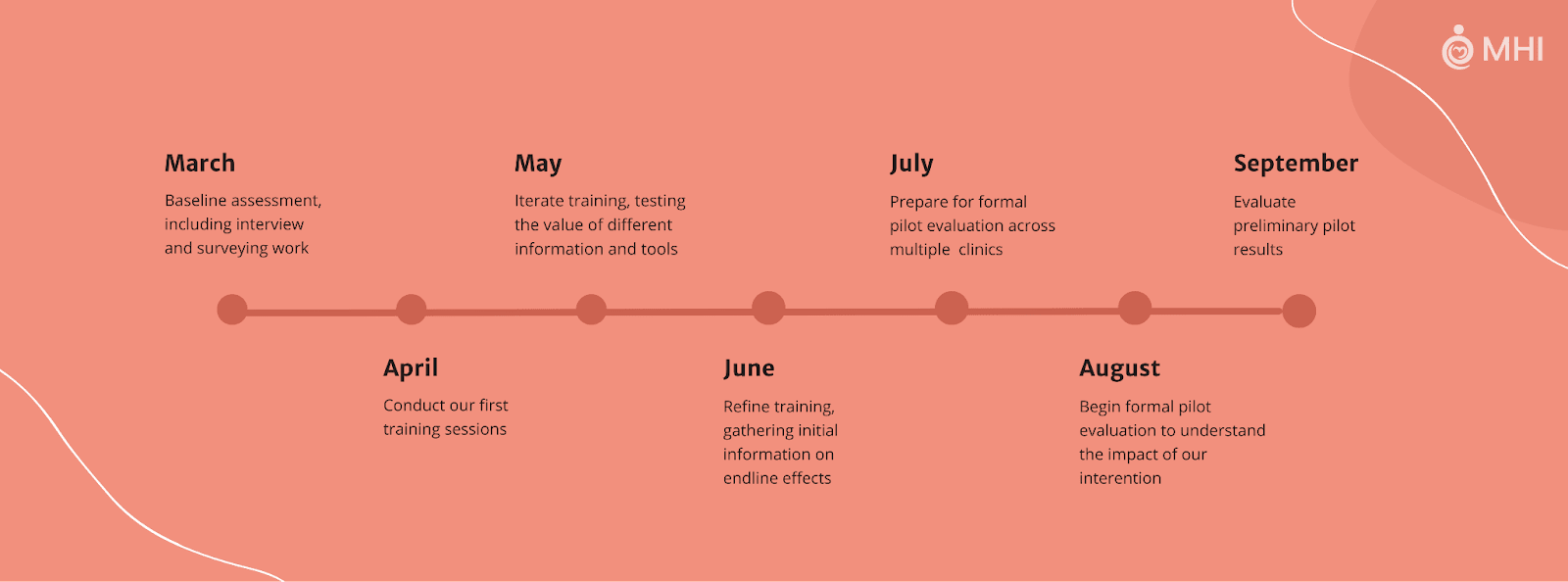

Through this trip, we were able to complete a rigorous assessment of the most promising location in which to pilot our intervention, synthesising lessons from expert interviews, DHS data, and local engagement. This led us to selecting northern Ghana as a focus region for our intervention and we are excited to now be underway with our pilot work there. At present, we are partnering with local organisations based in Tamale, the capital of the Northern region of Ghana, to conduct a baseline analysis of drivers and barriers to contraceptive uptake.

In the next month we will run our first training sessions, giving us an initial indication of our potential impact. From there, we will then iterate our approach, with plans to run a formal pilot evaluation in August. By October, we intend to have these results analysed, demonstrating either the cost-effectiveness of our work or the need for MHI to pivot in its operations.

Long-term plans

Assuming our proof of concept and pilot work delivers promising results, we want to work with the Ghana Health Service and other major stakeholders to scale these training improvements nationwide.

Once we’ve demonstrated the efficacy of our work, it appears promising to shift from a direct delivery approach to one of technical and financial assistance to the Ghana Health Service in making this standard, long-term practice.

We are also excited about exploring a number of additional avenues to achieving impact at scale. As an organisation targeting quality improvements to the care women receive pre- and post-birth, we may be particularly well-placed to expand our programming to include other highly promising areas in maternal and child health. Examples of these include micronutrient supplementation, mother-to-child Hepatitis B transmission, and antihypertensive medication[9].

Separately, we are optimistic about our ability to engage with the broader family planning and global health communities. With feasible pathways to long-term funding outside of effective altruism, we are excited about the potential for MHI to forge a pathway for future effectiveness-oriented family planning organisations.

Additional Information

About us

The Maternal Health Initiative is co-led by Sarah Hough and Ben Williamson. Prior to founding MHI, Sarah provided strategic guidance on healthcare regulation in her last role in the California civil service, having previously worked as a research assistant for Martha Nussbaum. In the year before setting up MHI, Ben founded and led Effective Self-Help, an EA-funded research organisation studying wellbeing and productivity.

As co-founders, we are well-supported by a growing team of volunteers and a network of advisors with broad expertise. Our advisors lead some of the most cost-effective global health organisations founded by the EA community and have conducted leading academic research across sub-Saharan Africa.

Uncertainties

Modelling the full impacts of family planning work is complex. We are currently working to expand our cost-effectiveness analysis to include a broader range of effects, integrating the impacts of our work on autonomy and other areas into the endline estimate of our impact.

We believe that family planning may be particularly impactful when the full breadth of its impacts are modelled in comparison to benchmark interventions such as cash transfers or malaria net distribution. By focusing on only one or two metrics, two interventions may appear similarly impactful when in fact there is an order of magnitude difference in their outcomes. Through our pilot evaluation and modelling, we plan to demonstrate whether or not this is the case for our work on family planning.

More broadly, we acknowledge that certain philosophical frameworks that prioritise utility maximisation may disagree with the impactfulness of family planning work. We do not find these views convincing but appreciate that people may hold differing philosophical perspectives in good faith.

Further Reading

For further information about MHI and the evidence base for our intervention, we recommend the following sources:

- Our website - Maternal Health Initiative

- Blog post summarising our in-person engagements in Sierra Leone and Ghana through January and February 2023

- High Impact Practices report written by a team of experts for USAID and the Gates Foundation

- EA Forum post on the potential impact of family planning work more broadly

Follow our work

If you’re excited about MHI’s mission, please follow us on our journey through our newsletter, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

Funding

Thanks to the generous funding we received at our outset, we have the financial runway to conduct and evaluate our pilot activities. While this means that MHI is not actively looking for funding currently, we welcome donations from individuals particularly excited about our work and plans.

Volunteer

At present, MHI is lucky to benefit from the work of a small number of talented, hard-working volunteers. If you’d be interested in contributing to our work, we have an open volunteer application and would be happy to explore how we can support you in upskilling whilst making a meaningful contribution to our mission.

Thanks for reading!

Thank you Ben and Sarah for your post. Your commitment to saving and improving the lives of mothers in extreme poverty is very admirable.

These uncertainties may matter more than most people realize.

Many EAs believe that creating happy lives is good. Will MacAskill writes that "if your children have lives that are sufficiently good, then your decision to have them is good for them."[1] Toby Ord writes that "Any plausible account of population ethics will involve…making sacrifices on behalf of merely possible people."[2] Both Will and Toby place moral weight on the non-person-affecting view, where preventing the creation of a happy person is as bad as killing them!

Using moral uncertainty, let's say there's only a 1% chance that the non-person-affecting view is true. In sub-Saharan Africa, 37% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion, leading to 8.0 million abortions per year.[3] This implies there are 21.6 million unintended pregnancies per year, leading to 200k maternal deaths.[4] To prevent one maternal death, one would have to prevent 108 unintended pregnancies on average. Even with only a 1% chance that the non-person-affecting view is true, this intervention is still net negative, because it causes 1.08 deaths (in expectation) to avert one maternal death.

The non-person-affecting view is mainstream among longtermists, and even non-longtermists may be willing to grant a small probability that we should care about future people.

Possible Objections

Some prevented unintended pregnancies will be replaced by others, so preventing one unintended pregnancy doesn't necessarily mean preventing one future person

This is a legitimate point, not factored into the above analysis, but all it does is just change one's maximum credence in the non-person-affecting view for the intervention to not be net negative. 50% replacement means a <2% credence; 75% replacement means a <4% credence.

People in extreme poverty may live net negative lives

This is debatable. Either way, if one believes this, they're arguing that many EA charities in global health and development are net harmful, because they save the lives of people in extreme poverty. This would also mean MHI's purpose of saving the lives of mothers in extreme poverty is a bad thing.

Saving human lives is net harmful, because of the meat-eater problem

This is also debatable, because humans seem to reduce wild invertebrate populations, and there are many ethical arguments pointing to these invertebrates living net negative lives. There's some reason to believe that this dominates our (horrific) treatment of farmed animals. As before, if you believe this, you should protest most EA charities in global health and development, and disagree with MHI's purpose of saving the lives of mothers in extreme poverty.

How does MHI incorporate moral uncertainty into its analyses of the net impact of its interventions?

MacAskill, W. (2022). What We Owe the Future (p. 250). Basic Books.

Ord, T. (2021). The Precipice (p. 263). Hachette Books.

https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/abortion-subsaharan-africa

https://ourworldindata.org/saving-maternal-lives

I'm not sure supporters of non-person-affecting views would endorse this exact claim, if only because a lot of people would likely be very upset if you killed their friend/family member.

From the perspective of long-termism, it seems plausible to me that countries with very rapidly growing populations, and that don't allow women the ability to control whether and when to reproduce, may be less politically stable themselves and may also contribute to increased political instability globally (I have no evidence to support this - happy to be corrected). My intuition is that increasing global political stability and improving quality of life should be a key priority for longtermists over the next hundred years (after reducing x-risk), and once this is achieved more emphasis can be put on increasing population - if humans/posthumans/AGI in the future decide this is a good idea.

>I'm not sure supporters of non-person-affecting views would endorse this exact claim

I'd put it more strongly - I think the original comment puts words in people's mouths that I don't think they mean at all.

Hi Julia. Thank you for your charity in our previous interactions.

Please let me know how you feel my comment puts words in people's mouths. I'll happily fix or retract any part of that comment which is misleadingly put.

It implies that Will and Toby believe that preventing the creation of a happy person is as bad as killing them. I think that's pretty unlikely, because most people who value future lives think murdering an existing person is a lot worse than not creating a life.

Thanks for the clarification!

I don't think my statement that Will and Toby "place moral weight" on the non-person-affecting view implies that they accept all of its conclusions. The statement I made is corroborated by Will and Toby's own words.

Toby, in collaboration with Hilary Greaves, argues that moral uncertainty "systematically pushes one towards choosing the option preferred by the Total and Critical Level views" as a population's size increases.[1] If Toby accepts his own argument, this means Toby places moral weight on total utilitarianism, which implies the non-person-affecting view.

Will spends most of Chapter 8 What We Owe The Future arguing that "all proposed defences of the intuition of neutrality [i.e. person-affecting view] suffer from devastating objections".[2] Will states that "the view that I incline towards" is to "accept the Repugnant Conclusion".[3] The most parsimonious view which accepts the Repugnant Conclusion is total utilitarianism, so it's unsurprising Will endorses Hilary and Toby's placing of moral weight on total utilitarianism to "end up with a low but positive critical level".[4]

I don't think Will and Toby believe that preventing the creation of a happy person is as bad as killing them. (Although I do personally think that's the logical conclusion of their arguments.) The statement I actually made, that Will and Toby "place moral weight" on that view, seems consistent with their writings and worldviews.

Greaves, Hilary; Ord, Toby, 'Moral uncertainty about population ethics', Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, https://philpapers.org/rec/GREMUA-2

MacAskill, W. (2022). What We Owe the Future (p. 250). Basic Books. p. 234

Ibid. p. 245

Ibid. p. 250

I think this somewhat conflates people's philosophical views and their gut instincts. (For what it's worth, I support the non-person-affecting view, and I would endorse that moral claim.) The quote is similar to:

I also have a weak intuition that a rapidly growing population contributes to political instability. However, population growth should increase our resilience to disasters, including nuclear war and bio-risk. Population growth also increases economic growth. This EA analysis of the long-term effects of population growth finds population growth to be net positive, mainly due to its economic effects. Overall, I think the evidence points to population growth being net positive.