We’re 33 days out from the midterm elections. Some of you have asked how we could be using the US political system to help farm animals. Here are some thoughts.

Should we engage in US politics?

It’s not obvious it’s worth engaging in US politics at all: Congress has never passed a law protecting animals in factory farms; the last attempt, in 2010, secured just 40 cosponsors. (A more limited 2012 compromise with the egg industry secured 149 cosponsors, but still failed.) Even the most liberal state legislatures — California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York — have rejected basic farm animal welfare bills. And advocates have had more success by other means, for instance by securing corporate animal welfare policies that exceed the strongest state laws.

But even if legislators won’t help farm animals anytime soon, they can still do great harm. State legislators in factory farming states have restricted common plant-based food labels (Missouri and North Carolina), banned undercover investigations via “ag-gag” laws (Idaho, Iowa, Missouri, North Carolina, and Utah), and even forced grocers to sell caged eggs (Iowa). Federal legislators are currently trying to preempt state farm animal welfare laws and put the industry-friendly USDA in charge of regulating clean meat.

In the longer term, politics might also present an opportunity for positive reforms. In three separate polls this year, 41% of US respondents said they care more about animal welfare than any other cause, 47% agreed that “animals deserve the exact same rights as people to be free from harm and exploitation,” and 47% even agreed that “I support a ban on slaughterhouses.” This may suggest broad popular support for reforms — or simply that novel survey questions elicit odd answers; 77% of US respondents told a 2012 survey that there are signs that aliens have visited Earth.

Either way, the recent political track record suggests that we have more hope of blocking bad bills for farm animals than advancing good ones — at least for the next decade. This suggests a different political strategy: instead of seeking to build legislative majorities, we may want to focus on supporting the few strong allies who can reliably block bad bills, and defeating the few enemies who introduce those bills. So who are our allies and enemies in Congress?

Rural Democrats or urban Republicans?

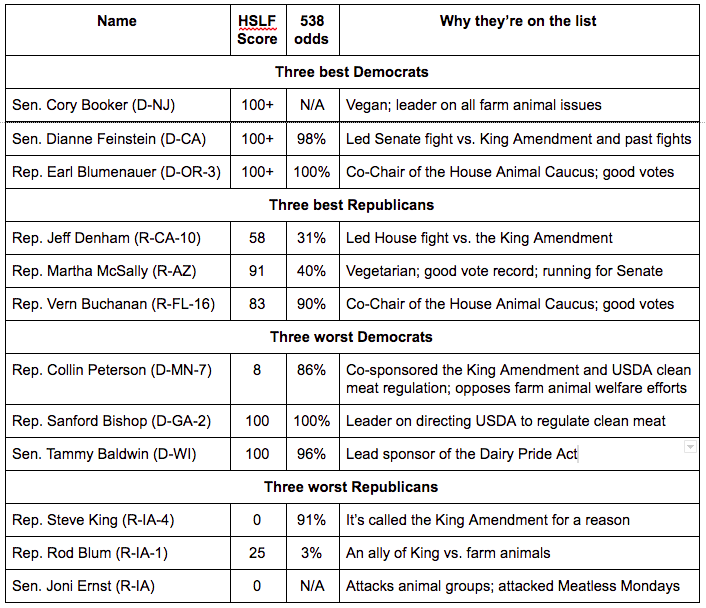

The next question is who to support. The usual framing pits Democrats against Republicans. On that score, it’s not close: of the 40 cosponsors on the last comprehensive farm animal welfare bill, just two were Republicans. Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) is a vegan, while Rep. Steve King (R-IA) is a shill for big ag. The Trump Administration even put a full time opponent of animal welfare reforms in charge of its transition at the USDA.

But the more important division may be between urban and rural politicians. Rural Democrats are typically bad on farm animal welfare: see House Agriculture Ranking Member Colin Peterson’s (D-MN) support for the King Amendment, or Sen. Tammy Baldwin’s (D-WI) introduction of the Dairy Pride Act. And some urban Republicans are good on the issue: see the 17 House Republicans who signed a letter in opposition to the King Amendment, most of them from California (95% urban), Florida (91%), New Jersey (95%), and New York (88%).

This is true historically too: an urban bipartisan coalition enacted the few federal laws protecting farm animals, over the opposition of rural politicians. In 1906, Northeastern senators led by Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA) defended the humane farm animal transport law against an attack from rural Western senators. In 1958, Republicans and Democrats voted in similar numbers for the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act, which was opposed largely by Southern Democrats. In 1978, two Republican senators and seven Democratic representatives led on a bill that strengthened the Act. And in 2002, Chicago's Sen. Peter Fitzgerald (R-IL) and Bethesda's Rep. Constance Morella (R-MD) led a bipartisan group on a resolution to increase humane slaughter enforcement.

Strategically, I think it makes sense to focus on fostering this urban bipartisan coalition. First, for defensive purposes: if we give up on urban Republicans, we’ll give up on stopping harmful bills when Democrats aren’t in power. Second, for offensive purposes, since a Democrat-only strategy can only pass a law when Democrats control the Presidency, House, and a 60-seat filibuster-proof majority of the Senate — and even then likely wouldn’t, due to the opposition of rural Democrats. Third, because this has worked for other movements: women’s suffrage, the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, and the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act all passed with a similar urban bipartisan coalition. Fourth, because this gives us an easier majority: although the Senate’s setup disproportionately favors rural states, just 19% of Americans live in rural areas.

What should we do now?

I doubt we should make political contributions this cycle. Most of the key races aren’t close: of the five worst reps for farm animals, two (King and Peterson) are in safe districts, one (Blum) looks set to lose, and two (Bob Goodlatte (R-VA-6) and Robert Pittenger (R-NC-9)) are retiring. And in the two relevant races that are close, many advocates will feel torn: Denham and McSally are the best candidates for farm animals, but their election could tip the House or Senate toward the Republicans. Plus, even there, it’s not clear how much difference marginal contributions will make — McSally alone has already raised $7.5M, and is supported by $6M in outside spending.

Nor do I think we should spend on helping Democrats flip the House or Senate for farm animals’ sake, though there are of course other reasons to do so. Small donations seem unlikely to influence the overall result, given the more than $4B likely to be spent on the midterms. And it’s unlikely that a Democratic Congress would pursue any positive reforms for farm animals. The best hope is that they’d block bad measures, like the King Amendment, but marginal Republicans like Denham are already likely to do that.

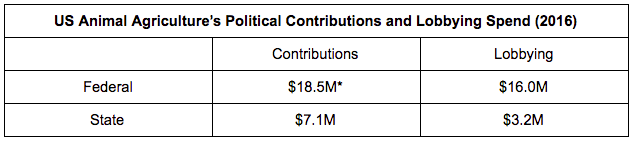

I do think, though, that it makes sense to start investing in a longer-term political strategy. The US farm animal movement may take years to match the $45M/year that animal ag spends on political contributions and lobbying (though matching just a fraction of that might be sufficient, given it's mostly not focused on animal welfare issues). But we should be able to surpass animal ag's mobilization sooner. The Census Bureau’s most recent statistics show just 1M "farmers and ranchers," "meat, poultry, and fish processing workers," and "miscellaneous agricultural workers" combined. Even this generous total — which includes vegetable farmers and farm workers unlikely to support animal ag — is dwarfed by the 7-20M Americans who identify as vegetarians (and even by the 3M who actually are).

In the meantime, for this election cycle I recommend donating or volunteering for California’s Prop 12, which would enact the strongest farm animal welfare law in the nation — in the nation's largest state. This would directly improve the welfare of about 40M layer hens, 700K pregnant sows, and 100K veal calves each year. It would force companies to start implementing the crate-free and cage-free promises they’ve made in recent years. And it would remind politicians that, when Americans get a choice, they vote to protect farm animals.