The meat and dairy industries’ war on alternatives to their products is underway. In May, meat lobbyists got US House lawmakers to insert language into a spending bill directing the USDA to regulate all meat and poultry grown from cells. After the FDA held a surprisingly balanced forum on such “clean meat,” which it indicated its intention to regulate, the American Farm Bureau joined with all the major animal ag groups to lobby President Trump to put the USDA in charge. This may seem like an obscure jurisdictional dispute. But the stakes could be high: one FDA and USDA law expert told a gathering that if the animal ag-friendly USDA regulates clean meat it “will not see the market in the lifetime of anyone in this room."

Plant-based meat and dairy are also under attack. In May, Missouri mandated that only “harvested production livestock or poultry” can call itself “meat.” In June, North Carolina directed its bureaucrats to “prohibit the sale of plant-based products mislabeled as milk.” And in July, the FDA signaled interest in policing the use of “milk” on plant-based milks — something the dairy industry has lobbied for since 2000. When Sens. Mike Lee (R-UT) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) introduced an amendment earlier this month to stop the FDA’s action, it was defeated 84-14 in the full Senate.

This is part of a global trend. The European Court of Justice ruled last year, in the well-titled Verband Sozialer Wettbewerb eV v TofuTown.com, that plant-based products could not use terms like “milk,” “cream,” or “cheese.” French cattle farmer and MP Jean-Baptiste Moreau followed up this April with a law that forbids the use of “names associated with products of animal origin” to market foods “containing a significant proportion of plant-based materials.” Dutch authorities even forced the Vegetarian Butcher to rename its “fish-free tuna” late last year, to the benefit of apparently deeply confused Dutch carnivores.

Why now?

The meat and dairy industries’ newfound interest in accurate labeling is partly a credit to the success of alternatives. In the 1980s, a Los Angeles Times poll named tofu the second-most hated food in the nation, while soymilk was sold in unappealing cartons that Silk’s founder called "Armageddon food.” Today, the Impossible burger is sold in >1,000 restaurants, including some White Castles; Beyond Meat is in >27,000 supermarkets and restaurants, including TGI Fridays; and clean meat startups are producing impressive prototypes. US plant-based startups raised $296M last year, according to Pitchbook Data, and clean meat startups scored the support of big-name investors like Bill Gates and Richard Branson. (Disclosure: we invested in Impossible Foods and support the Good Food Institute.)

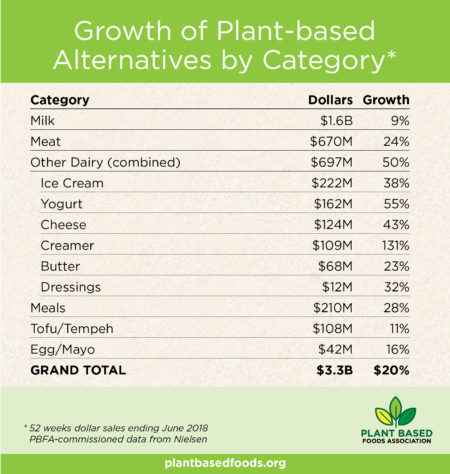

Market researchers are forecasting 7-8% annual compound growth in the $4B global meat substitute market. In the US, plant-based meat sales grew by 24% over the last year, while plant-based milks grew 9% to account for 15% of total US milk sales. About half of US food retailers now sell plant-based meat, and almost half of US consumers say they sometimes choose meat alternatives over chicken. In the UK, meat alternatives already make up 3% of the nation’s meat market, while Germany’s sector is expected to grow at 12% annually, aided by German meat giants launching new vegetarian versions of their meats.

But the move against meat substitutes isn’t exactly the last gasp of a dying industry: while US dairy sales have collapsed, US meat and poultry sales remain higher than ever. US plant-based meats still total just $670M in sales, or 0.3% of the roughly $200B in total sales of US meat. Instead, the meat industry seems to be seizing a window of opportunity. They know it’s easier to keep a product off the market than to remove it once it’s already there. And they know that the Trump Administration’s USDA is friendlier to animal ag than any future administration’s is likely to be — see its scrapping of rules to boost organic animal welfare standards and rights for contract poultry growers.

Should we worry?

So how bad is this? Some of the industry’s requests seem absurd enough to be rejected. The USDA likely won’t grant the cattlemen’s petition defining “beef” as “product from cattle born, raised, and harvested in the traditional manner,” since it would struggle to explain how artificial insemination and feedlots are traditional, while mock meats, which date to at least Song Dynasty China, are not. The FDA is more likely to issue new regulations than to enforce its current standard of identity for milk — “the lacteal secretion ... of one or more healthy cows” — if only because of those last two words: the latest USDA survey found a quarter of US dairy cows experienced clinical mastitis, a disease of the udder, during 2013, and the milk of these unhealthy cows still goes to market (unless they receive antibiotics). The USDA might even think twice before requiring the “lab produced” labels that industry wants on clean meat; chicken nuggets were likely first produced in a food science lab too.

Some of the new regulations are also likely illegal, while others may be irrelevant. Missouri’s law is likely preempted by the Federal Meat Inspection Act and Poultry Products Inspection Act, both of which forbid states from imposing additional requirements on meat labeling — a prohibition that courts have interpreted broadly. North Carolina’s law is likely preempted by the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which four federal courts have already found preempts state lawsuits claiming that plant-based milks are mislabeled. And even if the FDA can forbid the use of “soymilk” — which is not a legal certainty — it may not have much impact. In Canada, where plant-based milks have never been able to use the term “milk”, plant-based milk sales have risen while dairy milk sales have fallen, just as in the US.

But there’s also reason to worry. Meat lobbyists want the USDA in charge of clean and plant-based meats because they think it will stop these products from being called “meat.” They have good reason to think this: USDA officials have been meeting with meat industry lobbyists (and not clean meat startups) about labeling for clean meat since at least last August, and USDA top officials have long had a revolving door with animal product industries. (The irony is that the USDA only has regulatory authority over meat, poultry, and egg products; if it agrees with the lobbyists that clean meat is not meat, the USDA may lose its authority to regulate.) The USDA could keep new products off the market by rejecting them as misbranded, or by requiring endless pre-market safety testing, which could delay product launches for years.

And even if the FDA keeps primary jurisdiction over clean meat, the current attacks on clean meat could do lasting harm. The attacks of anti-GMO groups have likely caused clean meat startups to forswear technological tools that would accelerate research, and forced plant-based startups to do more animal testing (which has in turn earned them PETA’s scorn). And if the FDA accedes to the request of these groups and the meat industry to label clean meat as “lab-grown meat,” it’s a fair bet this will hurt consumer acceptance, given surveys show that framing heavily influences public acceptance of clean meat.

What can we do?

So what can you do to help stem the assault? The first thing is to tell regulators how you feel. The FDA is accepting comments on “Foods Produced Using Animal Cell Culture Technology” here through September 25. Opponents are already posting insightful comments like: “It is my hope that FDA doesn't call this meet [sic]. At best it is a food like product like American cheese.” The FDA will soon also open a comment period on milk labeling — watch this space.

Next, you can reach out to legislators. Animal agriculture’s influence is bipartisan: it got Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-MN) to introduce the Dairy Pride Act, which would ban the use of dairy terms on products not “obtained by the complete milking of one or more hooved mammals” (the bill’s authors wisely dropped the “healthy cows” requirement in the FDA language). Liberal luminaries Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Chris Murphy (D-CT) have since co-sponsored the bill, and all but four Democratic senators voted against the Booker-Lee amendment to stop the FDA’s action. (29 Democratic Senators, including Warren and Murphy, did, however, recently write in opposition to the King Amendment.) Animal advocates need to be equally bipartisan in their lobbying.

It may also be worth reaching out to agribusinesses with a stake in this fight. Last year Cargill and Tyson Foods made high-profile investments in clean meat startup Memphis Meats. Other agribusinesses have larger stakes in alternative proteins: meat giant Maple Leaf Foods owns Field Roast and Lightlife; dairy giant Danone owns Silk, So Delicious, and Vega; Kellogg owns Morningstar Farms and Gardenburger; and ConAgra is about to buy the owner of Gardein. Even animal feed giants like Archers Daniels Midland, DowDupont, and Roquette have invested in pea protein production. So far these agribusinesses have been silent in this fight — perhaps because alternatives remain a fraction of their total businesses, or because they fear offending their farmers. If they were to engage on behalf of their clean or plant-based investments, it could be significant in muting their trade associations and countering other industry lobbying.

Finally, you can follow or support the work of the Good Food Institute, the Plant-Based Foods Association, and New Harvest, which are all engaging with regulators on clean or plant-based meats.