TLDR: People plot benchmark scores over time and then do math on them, looking for speed-ups & inflection points, interpreting slopes, or extending apparent trends. But that math doesn’t actually tell you anything real unless the scores have natural units. Most don’t.

Epistemic status: I haven’t vetted this post carefully, and have no real background in benchmarking or statistics.

Benchmark scores vs "units of AI progress"

Benchmarks look like rulers; they give us scores that we want to treat as (noisy) measurements of AI progress. But since most benchmark score are expressed in quite squishy units, that can be quite misleading.

The typical benchmark is a grab-bag of tasks along with an aggregate scoring rule like “fraction completed”[2]

- ✅ Scores like this can help us...

Loosely rank models (“is A>B on coding ability?”)

Operationalize & track milestones (“can a model do X yet?”)

Analyze this sort of data[3]

- ❌ But they’re very unreliable for supporting conclusions like:

- “Looks like AI progress is slowing down” / “that was a major jump in capabilities!”

- “We’re more than halfway to superhuman coding skills”

- “Models are on track to get 80% by EOY, which means...”

- That's because to meaningfully compare score magnitudes (or interpret the shape of a curve), scores need to be proportional to whatever we're actually trying to measure

- And grab-bag metrics don’t guarantee this:

- Which tasks to include and how to weight them are often subjective choices that stretch or compress different regions of the scale

- So a 10-point gain early on might reflect very different "real progress" than a 10-point gain later—the designer could have packed the benchmark with tasks clustered around some difficulty level

(A mini appendix below goes a bit deeper, using FrontierMath to illustrate how these issues might arise in practice.)

Exceptions: benchmarks with more natural units

I’m most suspicious of Y-axes when:

- There’s no clear answer for what exactly the benchmark is trying to measure

- The benchmark is highly heterogeneous

- I can’t find a (principled) rationale for task selection and grading

And I’m more relaxed about Y-axes for:

- “Natural” metrics for some capability — benchmarks that directly estimate real-world quantities

- These estimates tend to be harder to get, but we don’t end up imposing fake meaning on them

Examples: METR’s time horizons[4], uplift/downlift studies (how much faster humans do X with AI help than without), something like "how many steps ahead agents can reliably plan", sheer length of context windows, agent profits, etc.

- “Toy” metrics with hard-coded units, where the scores are intrinsic to the activity

- These don't reflect quantities we care about as directly, but the measurements are crisp and can be useful when combined with other info[5]

Examples: Elo ratings, turns until a model learns optimal coordination with copies of itself, Brier scores

- Or unusually thoughtful “bag of tasks” approaches

- This might mean: committing to trying to measure a specific phenomenon, investing heavily in finding a principled/uniform way of sampling tasks, making the scoring and composition of the benchmark scrutable, etc. — and ideally trying to validate the resulting scores against real-world metrics

- I'm still cautious about using these kinds of benchmarks as rulers, but there's a chance we’ve gotten lucky and the path to ~AGI (or whatever we should be paying attention to) is divided into steps we'd weight equally by default

- Example: If I understand correctly, GDPVal is an attempt at getting a representative sample of knowledge work tasks, which then measures AI win rate in blinded pairwise comparisons against humans [6]

Does aggregation help?

We might hope that in a truly enormous set of tasks (a meta-grab-bag that collects a bunch of other grab-bags, distortions will mostly cancel out. Or we could try more sophisticated approaches, e.g. inferring a latent measure of general capability by stitching together many existing benchmarks.[7]

I’m pretty unsure, but feel skeptical overall. My two main concerns are that:

- Major distortions won't actually cancel out (or: garbage in, garbage out). There are probably a bunch of systematic biases / ecosystem-level selection effects in what kinds of benchmarks get created.[8] And most benchmarks don't seem that independent, so if 20 benchmarks show the same trend, that could give us something like 3 data points, not 20.

- Murkier scales: it’ll get harder to pay attention to what we're actually trying to measure

- You might end up burying the useful signal/patterns in other data, or just combining things in a way that makes interpreting the results harder

- And it’d probably be even more tempting to focus on fuzzy notions of capability instead of identifying dimensions or paths that are especially critical

I'm somewhat more optimistic about tracking patterns across sets of narrow benchmarks.[9] Ultimately, though, I sometimes feel like aggregation-style efforts are trying to squeeze more signal out benchmarks than benchmarks can give us, and distract us when other approaches would be more useful.

Lies, damned lies, and benchmarks

Where does this leave us?

Non-benchmark methods often seem better

When trying to understand AI progress:

- Resist the urge to turn everything into a scalar

- Identify and track key milestones or zones of capability instead of collapsing them into a number. tracking those directly instead of combining milestones and reducing that to some overall number. To talk about “how much better” models have gotten, just put sample outputs side by side.[10]

- Probably focus less on rate of progress and more on things like which kinds of AI transformations might come earlier/later, which sorts of AI systems will matter most at different stages, what the bottlenecks will be, and so on

- Focus more on real quantities

- E.g. AI usage/diffusion data, economic impact estimates (or at least stuff like willingness to pay for different things), or inputs to AI development (e.g. investment).

- These are laggier and harder to measure, but generally more meaningful

Mind the Y-axis problem

If you do want to use benchmarks to understand AI progress, probably do at least one of:

- Check the units first. Only take scores seriously if you've checked that the benchmark's units are natural enough[11]

- Assume squishy units. Treat grab-bag benchmarks as loose/partial orderings or buckets of milestones, and only ask questions that can be answered with that kind of tool (without measurements)

- This means no “fraction of the way to AGI” talk (from the benchmark scores, at least), no interpreting score bumps as major AI progress speedups, no extending trendlines on plots

- (I’m tempted to say that sharing “grab-bag benchmark over time” plots is inherently a bit misleading — people are gonna read into the curve shapes, etc.. But I’m not sure)

Improving the AI benchmarking ecosystem on this front could be worth it, too. I'd be more testing/validation of different benchmarks (e.g. seeing how well we can predict the order in which different tasks will be completed), or just investing more heavily in benchmarks that do have fairly natural scales. (METR's time horizons work has various limitations).

To be clear: what I'm calling "the Y-axis problem" here isn’t limited to AI benchmarks, and AI benchmarking has a bunch of other issues that I’m basically ignoring here. I wrote this because I kept seeing this dynamic and couldn’t find anything obvious to link to when I did.

Bonus notes / informal appendices

The following content is even rougher than the stuff above.

I. A more detailed example of the Y-axis problem in action

Let’s take FrontierMath as an example.[12] It consists of 300 problems that are generally hard for humans,[13] tagged with a difficulty level. If a model has a score of 50%, that means it’s solved half of those problems.

What does that score tell us about “true capabilities”?

Well, solving half the problems is probably a sign that the model is “better at math” than a model that solves a third of them — i.e. we're getting an ordinal measurement. (Although even that’s pretty shaky; success is often fairly evenly distributed across difficulty tiers,[14] and it looks like some models solve fewer lower-tier problems while beating others on the higher tiers. This weakens the case for there being a a canonical/objective ranking of task difficulty even just in this narrow domain; so a 30%-scoring model might actually be better at math than a 50%-scoring one, just worse at some incidental skill or a more specialized sub-skill of "math".)

What about actual quantities — does this help us estimate real measurements of mathematical skill, or AI progress at math? Not really, I think:

- Interpreting “the model solved half the problems in this set” as “we’re halfway to automating math” would obviously be silly

- It’s similarly unclear what a difference between a 30%-scoring and 50%-scoring model should look like — we can't just say the first is 3/5 of the way to the second

- And things like "sudden jumps" of 20% are hard to interpret. Without understanding the task composition and how it maps to a kind of "math ability" we're interested in, we can't really distinguish:

- "The new training regime genuinely accelerated math ability progress"

- vs. "The model cracked one skill that unlocked 60 similar-ish problems"

- We don’t really understand the composition of this set of questions and how that maps on to “AI math ability”, so unless we look under the hood, we can’t tell the difference between:

- 60 new problems were solved in one step because e.g. the newest training regime is great for math skill; it’s a real acceleration

- vs ... because they were fundamentally similar, and success on them was blocked by a single lacking aptitude

- We don’t really understand the composition of this set of questions and how that maps on to “AI math ability”, so unless we look under the hood, we can’t tell the difference between:

- The same issues apply to extrapolation

So to learn something useful you end up having to ask: which problems were solved? Do they reflect a genuinely new skill? Etc. But once you're doing that, the benchmark stops being a quantitative measure and becomes something more like a collection of potentially useful test cases.

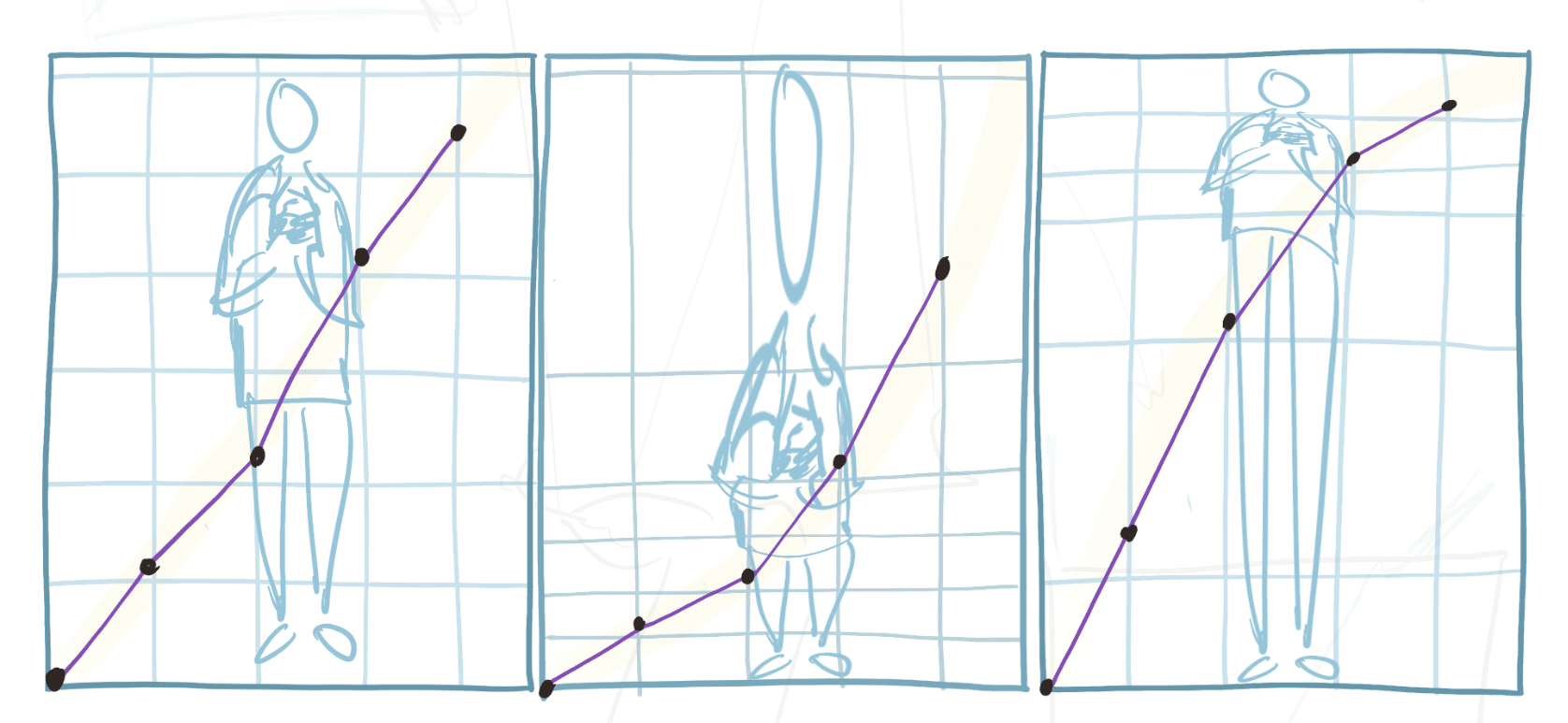

II. An abstract sketch of what's going on (benchmarks as warped projections)

My mental model here is:

A benchmark is a projection of some capability dimension we care about.[15]

- Unless it’s constructed very carefully, the projection will be pretty warped

- It stretches some regions (small capability gains become big score jumps) and compresses others (big capability gains become small score changes)

The extent and shape of that warping depends on how problems were sampled and grouped[16]

- When you’re plotting benchmark scores over time, you’re dealing with the warped projection, not measurements or trends in “true” capability-space.

- And to go from trend lines in the projection to trends in “true capability,” we’d need to undo the warping

But we don’t actually understand it well enough to do that[17]

In practice, how warped are existing benchmarks?

- I don't know; I'd be interested in seeing attempts to dig into this. But grab-bag-style benchmarks don't seem to see major jumps or plateaus etc. at the same time, and jumps on benchmarks don't always align with my gut takes on which systems were notable improvements (I'm not reviewing this systematically at all, though, so that's a weak take).

- At least right now, I generally expect that "shape of curve" signals people look at (for grab-bag benchmarks) are due to arbitrary features of the projection (artifacts of the task grouping or selection biases and so on). And overall I probably put more faith in my subjective takes than this kind of data for "fraction of tasks completed" benchmarks.

A potential compounding issue (especially for AGI-oriented benchmarks): not committing to a specific dimension / path through capability space

One thing that makes interpreting these benchmarks/projections harder — and tricks us into analyzing the numbers without knowing what they mean — is that no one agrees what dimension we're trying to measure. (There are probably also conflationary-alliance-like dynamics at play; many are interested in measuring "general capability" although they might have different visions for what that would mean.)

Especially for AGI-focused benchmarks (or ones where people are trying to measure something like "general intelligence" or "how much we're moving towards AGI"), it's really easy to stuff a bunch of deep confusion under the rug.[18] I don't have a sense of what the steps between now and ~AGI will be, and end up tracking something kinda random.

I think spelling out such pathways could help a lot (even if they're stylized; e.g. split up into discrete regimes).

- ^

You can see similar phenomena in broader misleading-y-axes & lying-with-stats discourse; see e.g. this. (And of course there’s a relevant xkcd.)

- ^

If I’m not mistaken, this includes FrontierMath, ARC-AGI, Humanity’s Last Exam, GPQA Diamond, etc. As I’ll discuss below, though, there are exceptions.

- ^

This can actually be pretty powerful, I think. E.g.:

- We can look at lags to see e.g. how close different types of models are, or how quickly inference costs are falling

- Or we can look at cross-domain benchmark patterns, e.g.: “Are models that beat others on X kind of benchmark generally also better at Y kind of benchmark?”

- Or, if we also gathered more human baseline data, we could ask things like “for tasks we know AI systems can do, how much cheaper/faster are they than humans”

In particular, ratios can help us to cancel out sketchy units, like "the exact amount of AI progress represented by a 1-point increase on a given scoring system". (Although ratios can still inherit problems if e.g. benchmarks are saturating, so catching up becomes meaningless as everyone hits the same ceiling.)

- ^

The longest time horizon such that models can usually complete software tasks that take humans that long

- ^

There's a tension here: narrow metrics are harder to generalize from (what does “superhuman at Go” mean for AI risk levels?). But within their domain, they're more reliable than broad metrics are for theirs.

Given how bad we are at making "natural" generalist metrics, I'd rather have weaker generalizability I can trust.

- ^

Alternatively, you could try to decompose some critical capability into a bunch of fairly independent sub-tasks or prerequisite skills. If you manage to (carefully) split this up into enough pieces and you’re willing to bet that the timing of these different sub-skills’ emergence will be pretty randomly distributed, then (even without knowing which will end up being “hardest”) you could get a model for how close you are to your ultimate target.

- ^

Or you could find other ways to use benchmarks to get ~meta-scores, e.g. testing coding agents based on how much it can improve a weaker model’s scores on some benchmarks by fine-tuning it

- ^

E.g. if existing benchmarks can’t distinguish between similar-ish models, there’s probably more pressure to find benchmarks that can, which could mean that, if released models are spread out in clumps on some “true capability” dimension, our mega-benchmark would oversample tasks around those clusters

- ^

E.g. ARC-AGI tries to focus on fluid intelligence specifically. If the approach is reasonable (I haven’t thought much about it), you could try to pair it with something that assesses memory/knowledge. And maybe you always check these things against some hold-out benchmarks to try correcting for hill-climbing, etc.

Then if you see “big jumps” at the same time you might have more reason to expect that progress truly is speeding up.

- ^

Maybe LMArena is a way to crowdsource judgements like this to translate them to numbers; I haven’t dug into what’s happening there. (I expect the units are still “squishy”, though.)

- ^

For me this is mainly METR’s time horizons. (COI note that I’m friends with Ben West, who worked on that project. Although in fairness I’ve also complained to him about it a bunch.)

- ^

I picked FrontierMath randomly (to avoid cherry-picking or singling anything out I just went here on December 20 and went for the top benchmark).

Here I'm talking about the original(?) 3 tiers; there's now also an extra-difficult “Tier 4” and a set of open problems on top.

Also, I'm pointing out limitations here without discussing how the benchmark can be useful or various things it got right.

- ^

Famously “difficulty for humans” doesn’t always map neatly onto “difficulty for AI”; the classic reference here is “Moravec’s paradox”. The phrase rattling in my head on this front is something like intelligence/capability tests require shared simplicity priors. “Contra Benchmark Heterogeneity” by Greg Burnham illustrates an important way in which this plays out in benchmarking. Quoting:

...It would be great if benchmarks predicted success at some practical task. For humans this can be done, at least in some domains, using academic-style tests. However, this relies on correlations in humans between test performance and practical performance, and we can’t rely on the same correlations in AI systems. Full-on simulation of the relevant task would be ideal for AI systems, but it will take significant investment to get there. In the mean-time, we can use academic-style tests for AI systems, but we should keep them narrowly targeted so we can keep a handle on what they measure.

Greg Burnham has also written some good stuff on FrontierMath specifically, including here. Quote:

My suspicion is that a significant chunk of FrontierMath problems can be solved by applying advanced mathematical techniques in relatively straightforward ways. If anything, this might obscure their difficulty to humans: most people don’t have the right knowledge, and without the right knowledge the problems seem impossible; but with the right knowledge, they aren’t so bad.

- ^

Today [in December] there’s a “Tier 4”, with especially difficult problems, and I’d guess the correlation is stronger there (I got a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient of 0.62 when I ran things in an extremely half-assed way, fwiw).

But it’s still not clear what it means if one system can solve [~40% of Tier 1-3 problems and ~20% of Tier 4 problems} and another can solve {60% of Tier 1-3 problems and ~5% of Tier 4 problems}, as it currently seems is the case with Gemini 3 Flash and Gemini 3 Pro. The point is basically that models aren’t steadily progressing through harder and harder questions.

- ^

If you want to simplify this, you can think of this as the one true number that represents how capable an AI system/entity is. Else:

There’s no canonical “capability dimension” (consider for instance that different models & entities find different tasks harder/easier, and also that there might simply not be a true way to rank a skillset that’s great at logic with a bad memory and its opposite). But we can often reasonably pick a specific dimension of capability to focus on; e.g. when we ask if timelines are speeding up/slowing down, we’re often asking something like “has progress on what we expect is the path to ~AGI been speeding up?” So the “true” dimension we’ll look for might become the expected-path-to-AGI dimension. Or we can zero in on particular skills that we care about, e.g. coding ability (although then it’s still useful to ask what the “true” metric you’re thinking of is).

- ^

If you really screw up this mapping, you’ll get more than warping. You could get, for instance, ~backtracking; scores going down as the “true capability we care about” goes up. I think we’re much better at avoiding that. (There’s a related situation in which we might see apparent “backtracks” like this: if we’re looking at a very specialized benchmark that isn’t on the path to whatever AI companies care about or very correlated with some deep “general intelligence” factor. That could go down when “true capabilities” go up, but I don’t think that’s necessarily a messed up projection. A better model here might be instead thinking of this as a projection of something else — some other dimension/path through capability space — and considering what relationship that thing has to the “true capabilities” dimension we’re thinking about.)

- ^

In fact I think often people (including benchmark creators, including ones focused on AI safety or similar) are very unclear about what it is that they’re actually trying to measure.

(There’s another relevant xkcd. )

- ^

Rugs include: a smoothed out pattern, a way of getting some "latent measure of general capability"

Very interesting critique. I've seen this kinds of comments in academic circles doing evals work, and there have been attempts to improve the situation such as the General Scales Framework:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.06378

Think of it as passing an IQ test instead of a school exam, more predictive power. It's not percect ofc but thankfully some people are really taking this seriously.