A new study on the burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was recently released with updated estimates of deaths and DALYs caused by drug resistant infections.

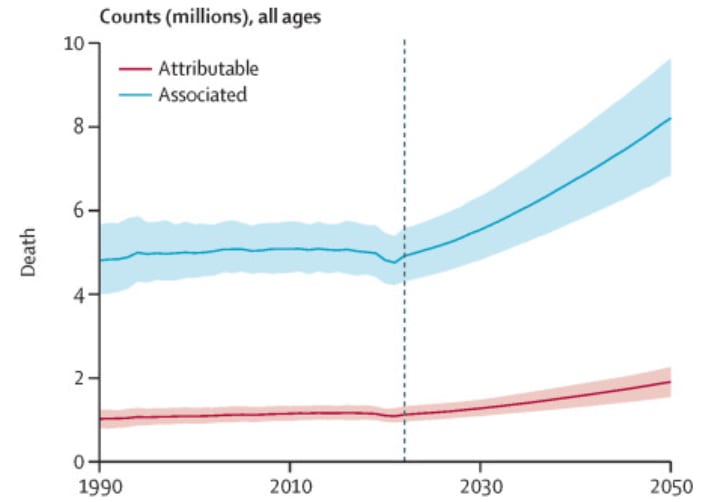

According to the Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050, 1.14 million deaths worldwide were directly attributable to bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in 2021 and 4.71 million deaths were associated with it overall (explanation of associated vs. attributable deaths below), with these figures slated to increase substantially to 1.91 and 8.22 million deaths per year respectively by 2050 (see also accompanying editorial and press coverage, as well as interactive visualisation tool). This study by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) Project builds upon the first GRAM report in 2022 which analysed the global scale of bacterial AMR for the first time, with this updated study being the first to analyse historical trends and provide policy-relevant forecast scenarios for all countries globally. It paints a sobering retrospective picture and warns of a worsening crisis, but it also provides hope and guidance for averting the worst effects of AMR. The study was released on the eve of the UN general assembly high-level meeting on AMR, which took place last Thursday (26th September), and led to the approval of a political declaration on AMR which sees countries commit to reduce AMR associated mortality by 10% by 2030 and the establishment of an independent evidence panel on AMR (an “IPCC for AMR”).

Some highlights from the new study:

Headline figures

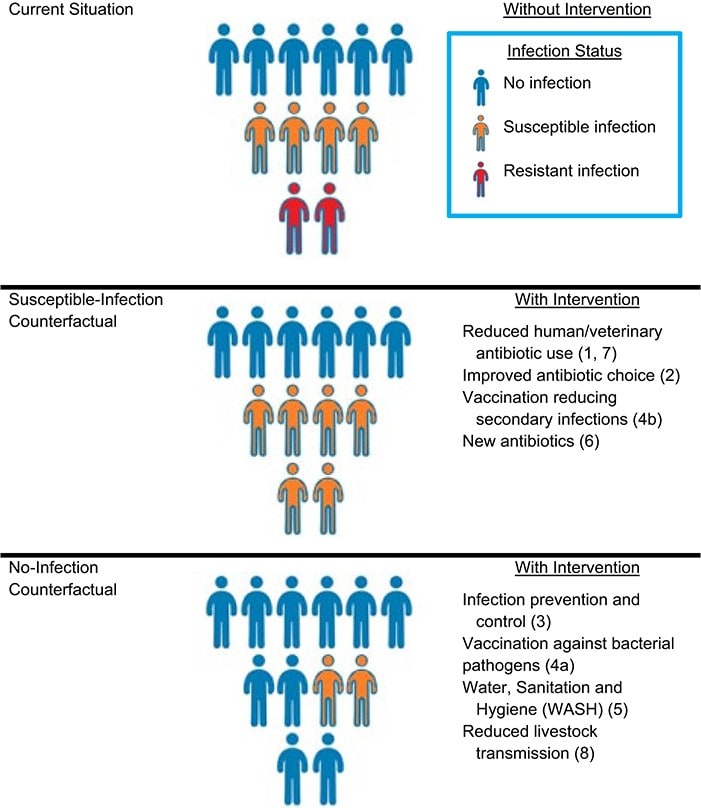

Bacterial AMR has been a leading cause of death worldwide since at least 1990 when the attributable death count had already surpassed a million, and it has been steadily rising since then, topping out at 1.20 million attributable deaths and 4.94 million associated deaths in 2019 before temporarily dipping during the covid-19 pandemic (of which more later). In discussing mortality and morbidity associated with AMR, the attributable burden is defined using a counterfactual in which all drug-resistant infections are replaced by equivalent drug-susceptible infections, which better describes the benefit of treating infections, such as through newly available drugs; in contrast the associated burden is defined using a counterfactual in which all drug-resistant infections are replaced by no infection, which better describes preventing infections, such as through vaccination campaigns and improved water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Over a million deaths a year worldwide have been attributable to bacterial AMR since 1990 and nearly 5 million a year associated with it, underscoring how AMR has been a leading cause of mortality for decades. This burden is set to increase dramatically in the coming years under the most likely scenario (more below). Figure from the new Lancet study

Infographic illustrating the difference between attributable disease burden, defined using the susceptible-infection counterfactual, and associated disease burden, defined using the no-infection counterfactual. Both measures are relevant in the AMR context for different policy-relevant scenarios. Source: Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance: Compared to What? by Marlieke E A de Kraker and Marc Lipsitch

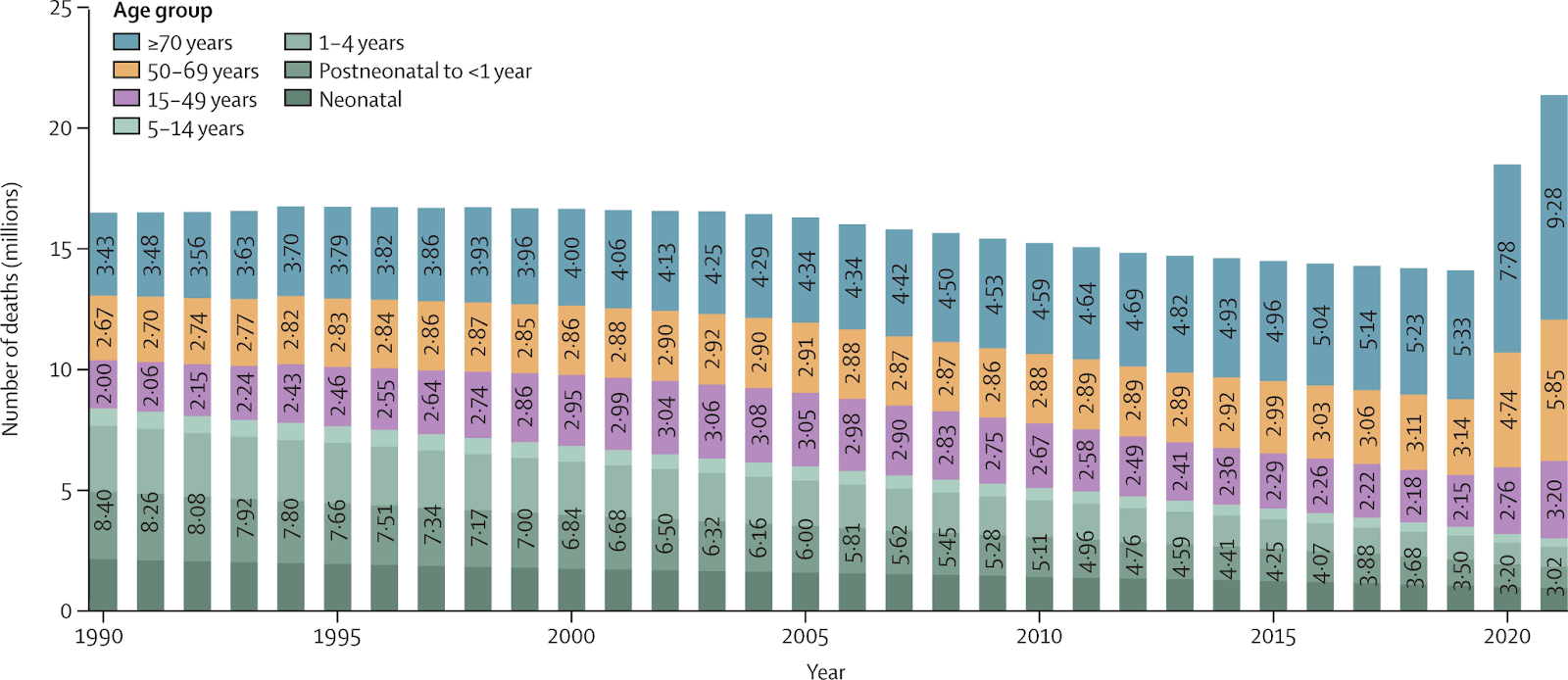

Age related trends

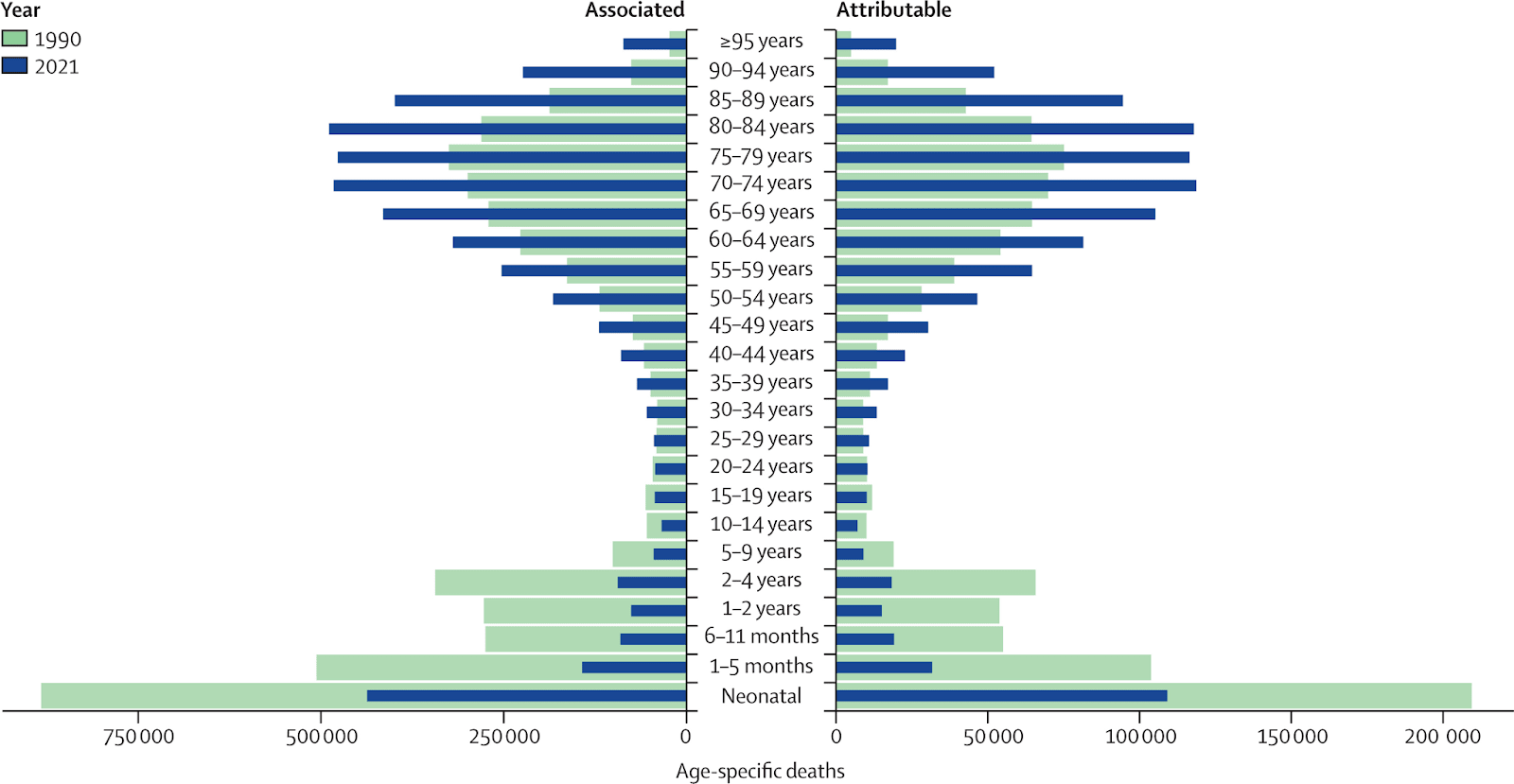

The historical total above masks a divergent age trend. Children under age 5 used to comprise nearly half of all AMR-attributable deaths globally in 1990, but the child death toll has since dropped by more than -50% since then due to infection prevention via widespread vaccination efforts and improved access WASH infrastructure. In contrast, all age groups over 25 have suffered increases in deaths, particularly in the elderly (ages ≥70) where the increase approaches an alarming +90%. The latter is concerning since, in tandem with the ever-ageing world population, interventions might be less effective in older adults (due to e.g. immunosenescence reducing vaccine efficacy), they are more likely to experience adverse effects from specific antimicrobials (compounded by the need to use more toxic second- and third-line treatments when first-line options fail due to resistance), and they are more likely to have comorbidities like obesity and diabetes that increase risk of opportunistic infections.

Globally, there has been a divergent age trend in AMR burden: both attributable and associated deaths have dropped substantially between 1990 and 2021 especially for children under age 5, but risen dramatically in older age groups in particular ages ≥70. Figure from the new Lancet study

Geographical differences

Geographically, the burden increase among older age groups explains why the world regions with the greatest increase in attributable deaths are not all LMICs, even though from a “snapshot” perspective the AMR burden itself is LMIC-focused. For instance, the US and Canada (i.e. “high-income North America”) experienced a greater increase in deaths than any other region except western sub-Saharan Africa and Tropical Latin America, partly due to the former’s older population on average; zooming out, the GBD high-income super region (North America, Western Europe, APAC, Australasia, and Southern LATAM) actually suffered a greater increase in AMR-attributable deaths than any other super region, further underscoring the changing nature of the AMR threat globally. That said, lower-income countries still bear ~90% of the AMR burden.

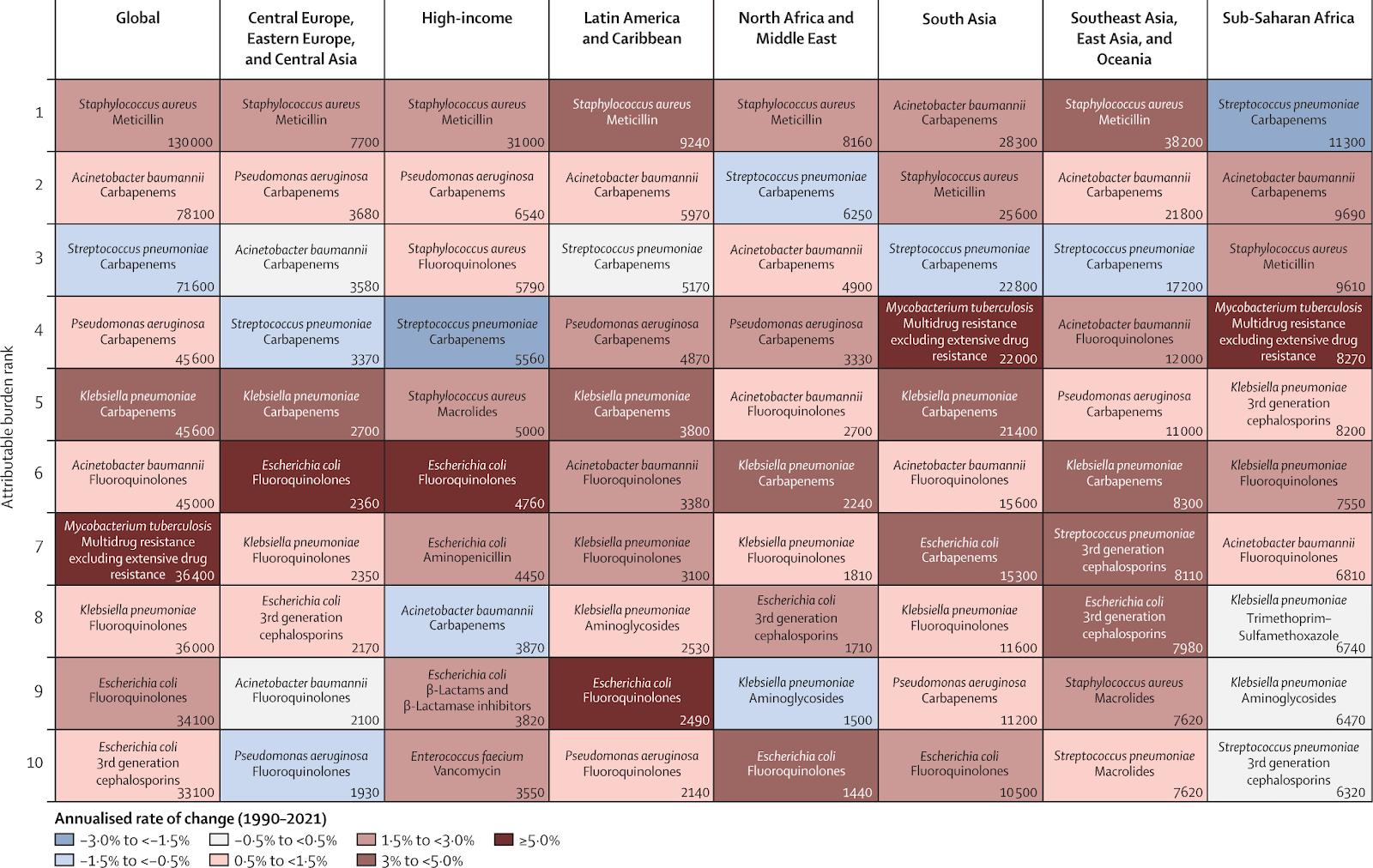

Bug/drug combinations

AMR-attributable deaths from resistance to carbapenems increased more than for any other antibiotic class at +89,200 additional deaths. This is particularly alarming given that carbapenems are considered by many to be a last-resort antibiotic, and that most future treatments in the later stages of drug development are derivatives of established antimicrobial classes so they are unlikely to treat carbapenem-resistant infections; this is reflected in WHO’s 2024 revision of the Bacterial Priority Pathogens List designating carbapenem-resistant A baumannii and Enterobacterales as ‘critical priority’. Zooming in, the pathogen-drug combination with the largest attributable burden was methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) whose global burden more than doubled from 57,200 deaths in 1990 to 130,000 deaths in 2021, followed by multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae, and carbapenem-resistant A baumannii. In contrast to MRSA, the new study notes that there are fewer evidence-based prevention measures for the lattermost two carbapenem-resistant organisms (CPOs), so research into prevention measures focusing on these organisms is urgently needed

Methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) was the deadliest pathogen-drug resistance combination in most world super regions, with multiple carbapenem-resistant organisms (CPOs) close behind. The latter are particularly concerning given that carbapenems are considered to be a last-resort antibiotic. Figure from the new Lancet study

Effects of the Covid-19 pandemic

AMR-attributable deaths dipped from 1.20 million in 2019 to 1.14 million in 2021 during the covid-19 pandemic due to myriad potential factors which the study briefly summarises: resistant pathogen transmission might have decreased due to the use of personal protective equipment, enhanced hand hygiene, and physical distancing; selective pressure for resistance might have decreased due to fewer antibiotic prescriptions in high-income countries; and mortality displacement (or “harvesting effect”) might have occurred in which older people and those with comorbidities were recorded as dying of covid-19 even if secondary bacterial infections contributed to their deaths. The study suggests this AMR mortality decrease is probably temporary due to the pandemic-specific factors above; additionally, AMR data during the covid years might have been biased downwards by AMR surveillance efforts being affected by the pandemic, so the true AMR death toll might have been higher

The global death toll from sepsis, which is a key input into the AMR burden estimates in the paper, spiked dramatically during the covid-19 pandemic especially among older people, yet for many their deaths would have been recorded as primarily due to covid-19 even if secondary AMR-related bacterial infections increased mortality likelihood; this mortality displacement or “harvesting effect” might have underestimated the true AMR burden during the pandemic. Figure from the new Lancet study

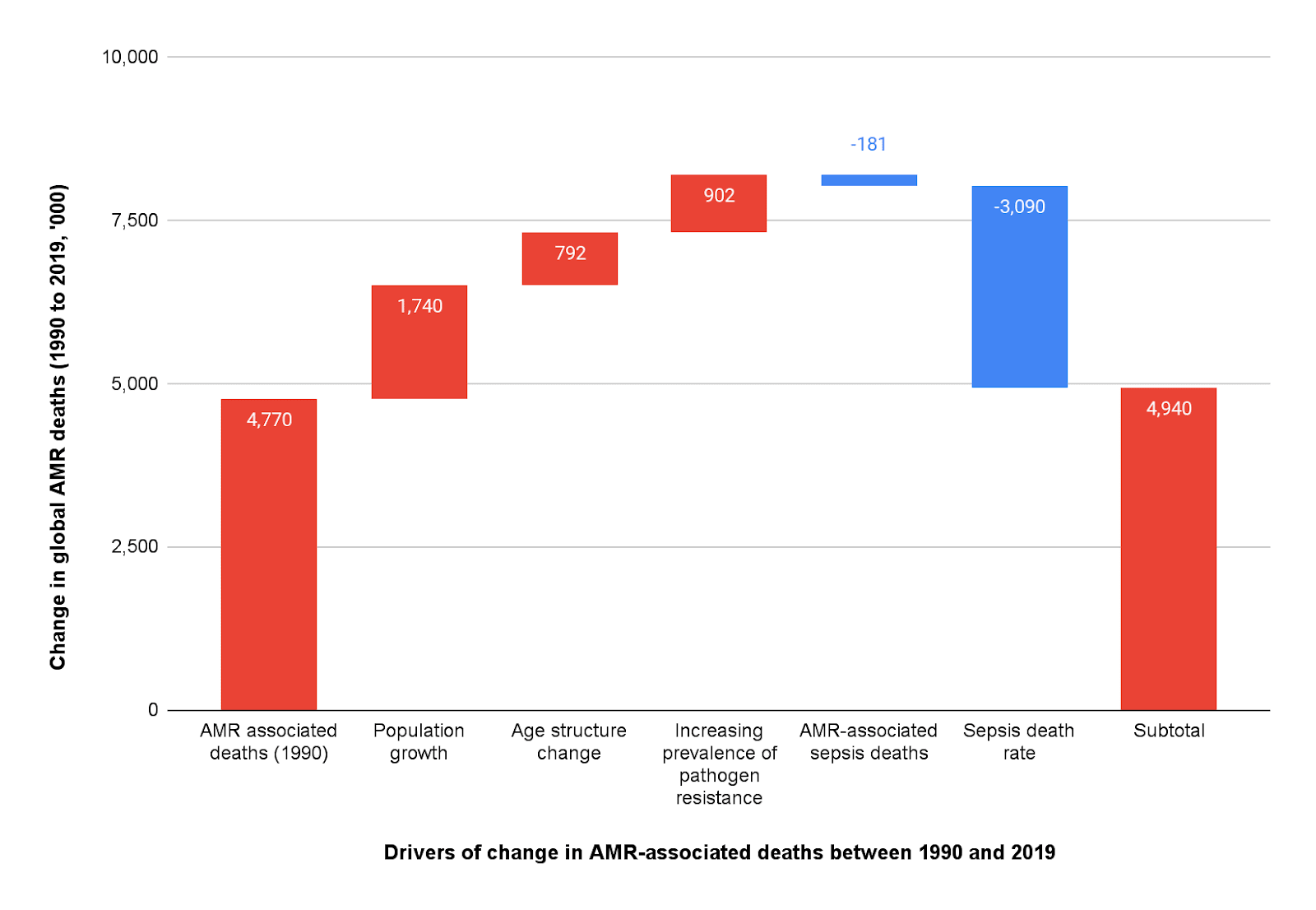

Drivers of change in AMR related deaths

That said there is another divergent historical trend, this time a hopeful one, revealed by decomposing the drivers of change in global AMR deaths: from the 4.77 million associated deaths in 1990, one would expect to see an additional +1.74 million associated deaths by 2019 due to population growth, +792,000 more deaths due to changing age structure (i.e. more adult deaths in an ageing world) and +902,000 more deaths due to increasing prevalence of resistance among pathogens, totaling up to a staggering +3.43 million more associated deaths by 2019 – yet in reality we “only” see 163,000 more deaths. This means an amazing 3.27 million deaths were averted in 2019 alone(!), mainly from reduced sepsis mortality in children under-5, which the study’s analysis attributes to better infection prevention, improvements in sepsis management, and better healthcare quality overall

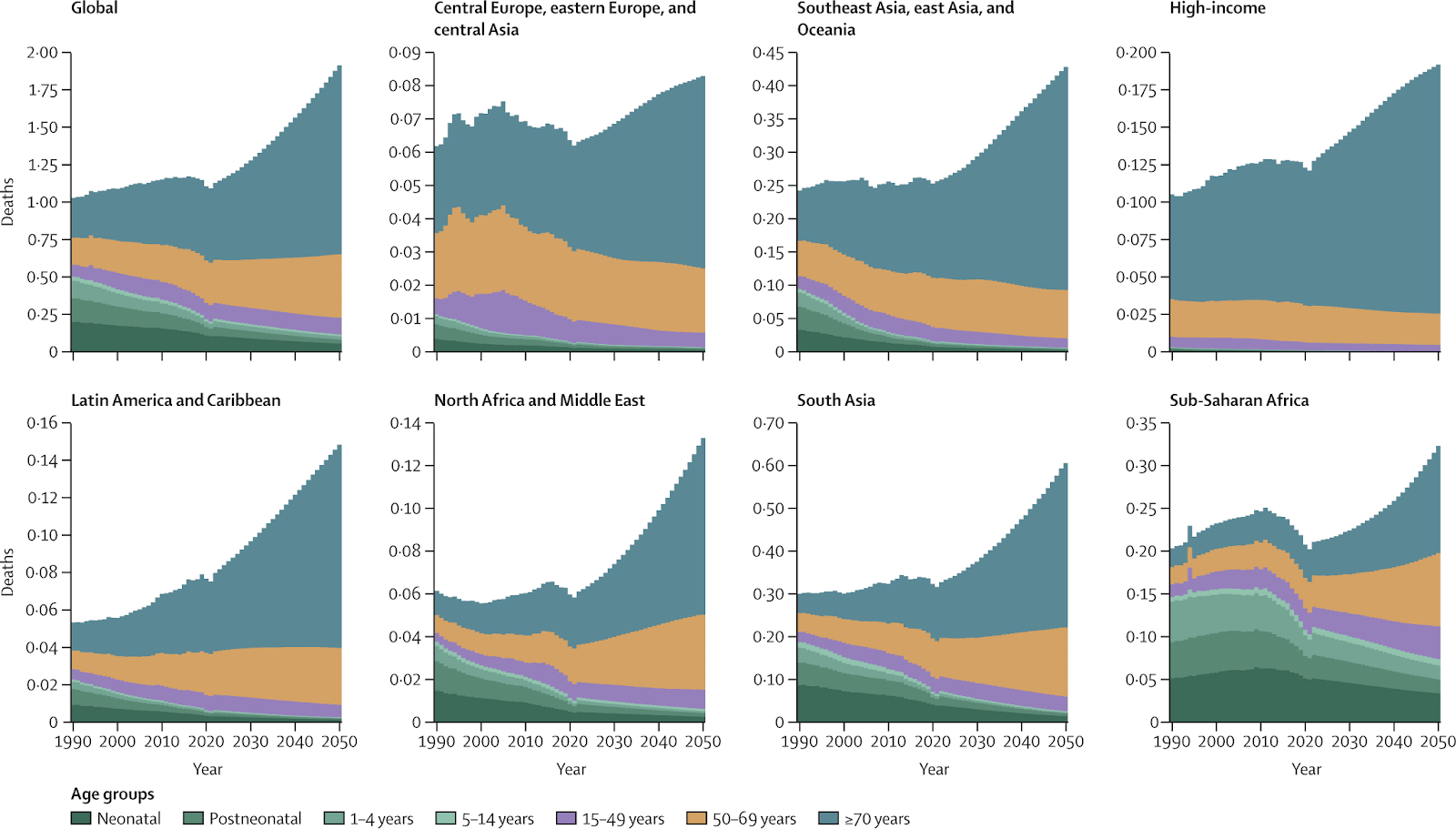

Forecasts for most likely future burden

Going forward, the global burden is forecasted in the most likely scenario to increase to 1.91 million AMR-attributable deaths and 8.22 million associated deaths by 2050, cumulatively totaling 39.1 million attributable and 169 million(!) associated deaths respectively from 2025 - 2050. Notably, the associated deaths figure is in the ballpark of the 2014 Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) landmark report which projected 10 million annual deaths caused by AMR by 2050, an estimate that helped position AMR as one of the most pressing health threats of the 21st century, and that latter estimate included malaria and HIV while this one does not. This burden would be highest in south Asia, southeast Asia, east Asia, and Oceania, and sub-Saharan Africa, and the net growth in burden would be driven mainly by increased deaths in older adults in all world regions overcoming declining deaths among children. Note that this forecast is potentially an underestimate, in that it does not include outbreaks of new resistant pathogens or “superbugs” as well as stochastic events that lead to a marked increase in infections and resistance

The global burden of AMR is forecasted in the most likely scenario to increase drastically in all world super-regions by 2050, driven primarily by the rising death toll in the elderly outpacing declining deaths in children. Note that this forecast is conservative, since it does not include outbreaks of new “superbugs” or other stochastic events that would markedly increase infections and resistance; anthropogenic global warming would increase the frequency of such events. Figure from the new Lancet study

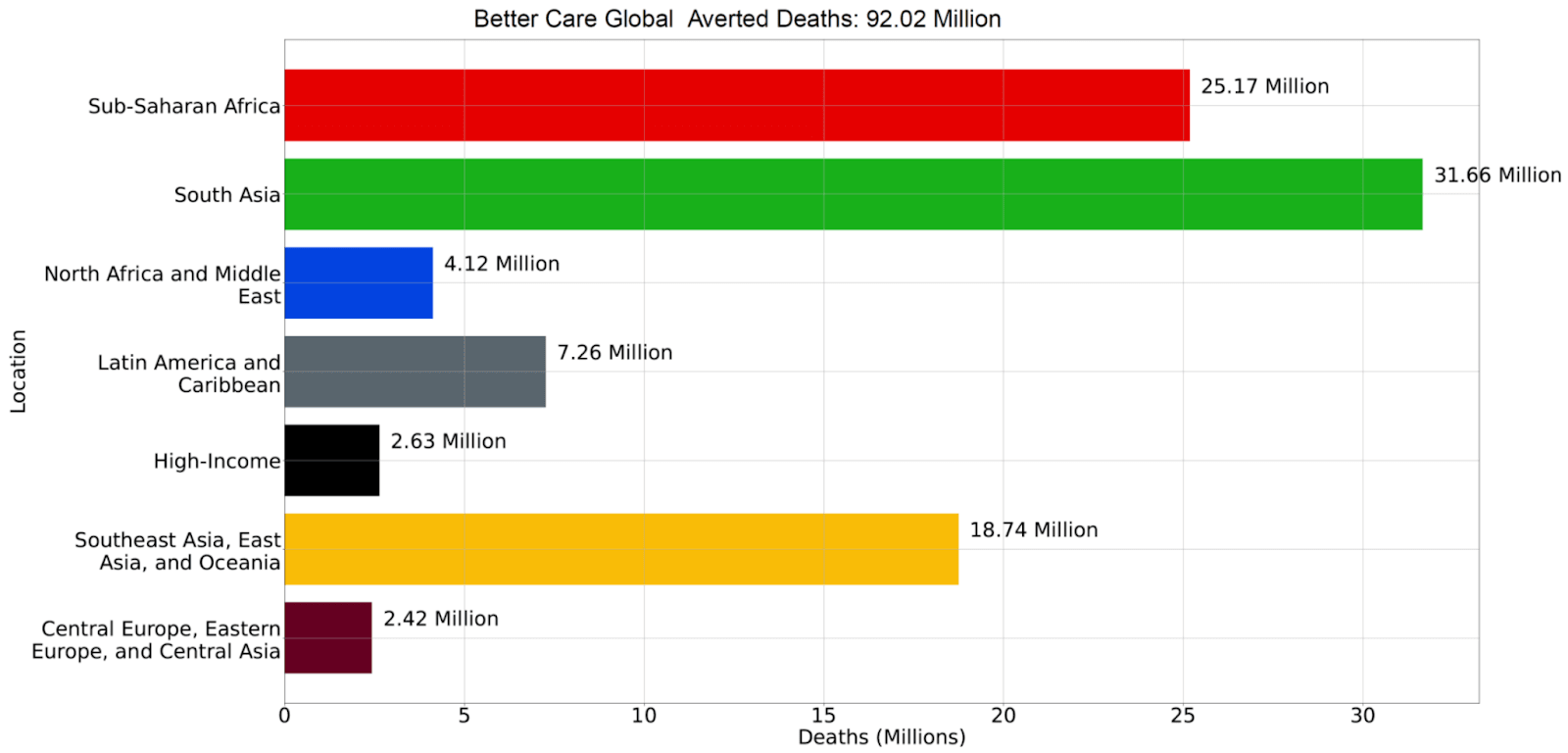

Forecasting with improved healthcare systems

The study forecasts 2 policy-relevant alternative scenarios. The first is the “better care” scenario, inspired by the hopeful trend just mentioned, assumes continued improvement in infection prevention and healthcare quality (meant to be construed broadly, including improved diagnostic capacity, a more robust healthcare workforce, and availability of life-saving technological interventions for people with advanced disease e.g. ventilators), coupled with better access to antimicrobials. The study projects the “better care” scenario to avert 92 million deaths cumulatively between 2025 - 2050. Geographically, the greatest benefits in this scenario would arise in the regions forecasted to suffer the highest burdens in the mainline scenario: south Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and southeast Asia, east Asia, and Oceania. Age-wise, deaths averted for people ages ≥70 would far outnumber those for children under-5 in all regions, except in sub-Saharan Africa where the benefit would be similar

The study projects the “better care” scenario to avert 92 million deaths cumulatively between 2025 - 2050, which assumes continued improvement in infection prevention and healthcare quality, coupled with better access to antimicrobials. The benefits would accrue primarily to older people in developing countries, although tens of millions of children would avoid dying of AMR infections as well. Figure from Appendix I in the new Lancet study

Forecasting for improved drug pipeline

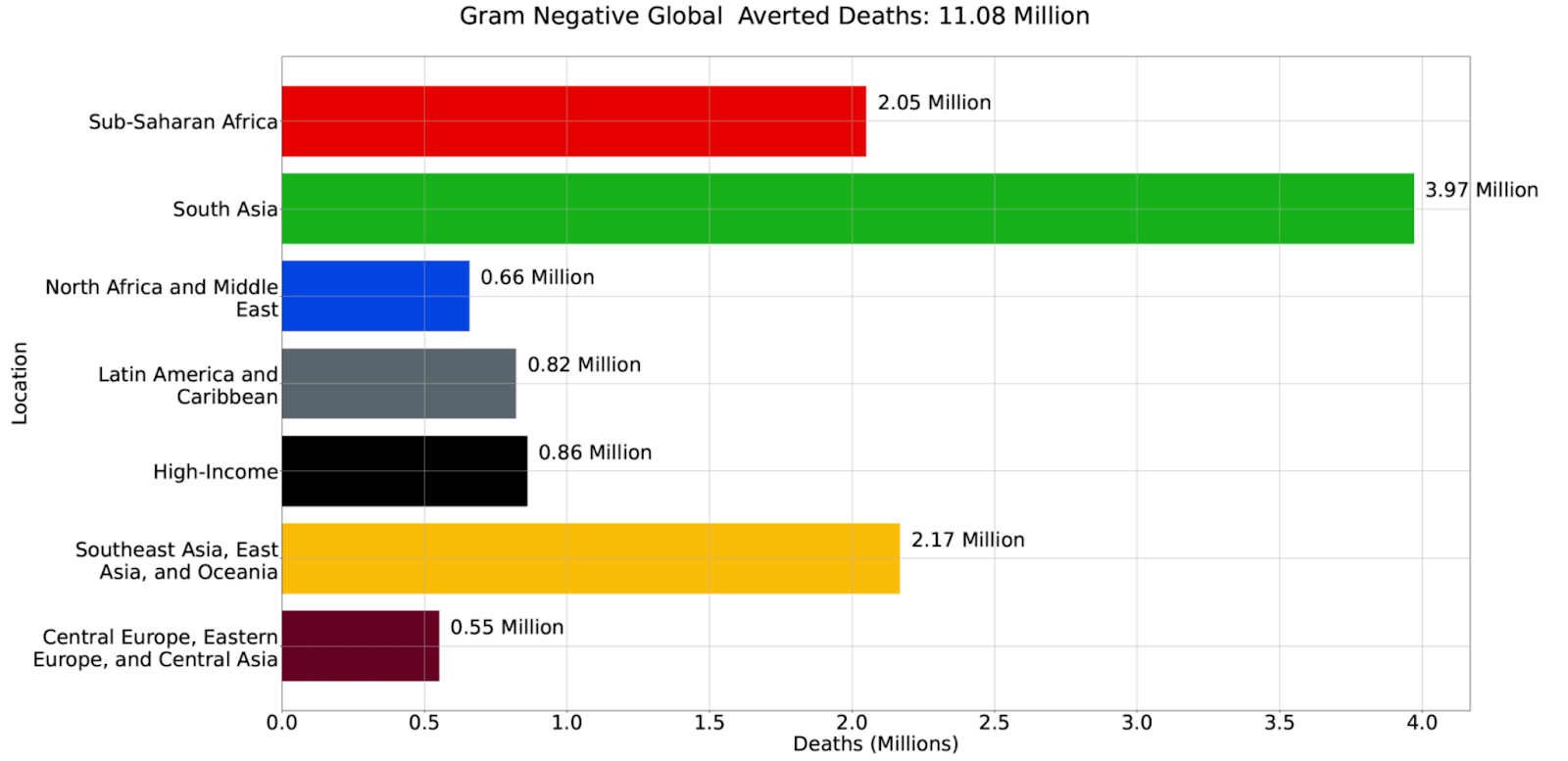

Besides the “better care” scenario, the study also forecasts a “Gram-negative” scenario in which a drug pipeline is adequately developed to regularly release new, potent antibiotics targeting Gram-negative bacteria, which are prioritised due to the alarming increase in carbapenem resistance mentioned above as well as the lack of existing and future treatment options. This scenario is projected to cumulatively avert 11.1 million deaths between 2025 - 2050, again primarily in the high-burden world regions previously mentioned and among older people. Notably, this figure is comparable to the 9.9 million deaths averted globally over 30 years forecasted by the CGD in their report modelling the return on investing in a program to incentivize antibiotic development, which lends credence to the study’s forecasted estimate. This program would be a pull incentive scheme, which is an example of a market-shaping intervention meant to address market failures that discourage investment into innovative resistance-breaking treatments (see also the discussion of pull mechanisms in this 80K podcast episode)

The study also projects the “Gram-negative” scenario to avert 11 million deaths cumulatively between 2025 - 2050, which assumes adequate funding and development of a global drug pipeline regularly releasing new, potent antibiotics targeting Gram-negative bacteria, in particular to address rising carbapenem resistance. Similar to the “better care” scenario, benefits would accrue primarily to older people in developing countries, although millions of children would avoid dying of AMR infections as well. Of course, as the study authors note, the “drug development vs better care” framing is a false dilemma; countries should fund and support both. Figure from Appendix I in the new Lancet study

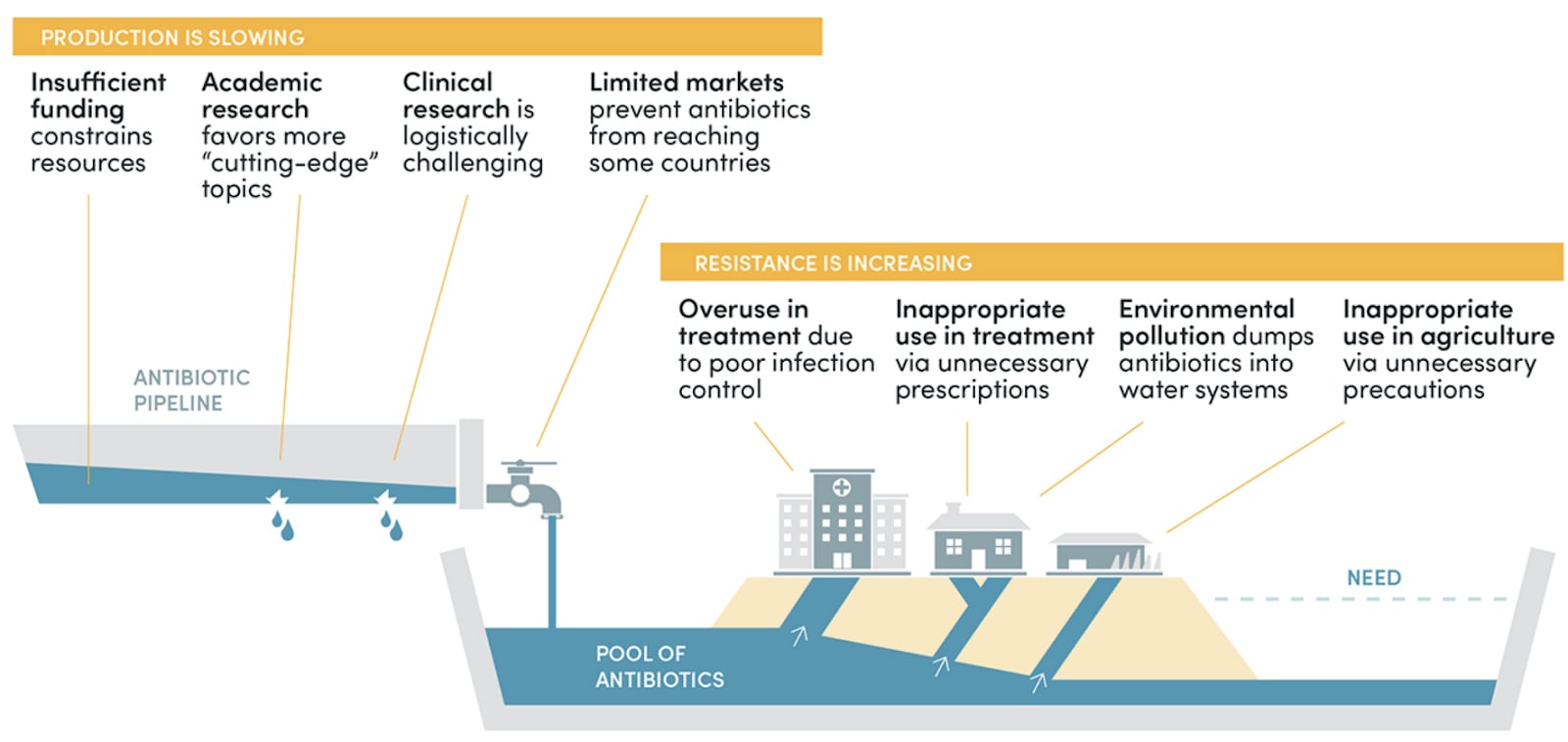

The tragedy of the (antibiotic) commons describes how global antibiotic development and supply is hamstrung by a bevy of market failures, neatly summarised in the infographic above from the recent CGD report The Economics of Antibiotic Resistance by Anthony McDonnell et al. Market-shaping interventions such as pull incentives aim to address these failures, thereby realising the potential benefit of saving 11.1 million lives in the Gram-negative alternative scenario forecasted in the study; see for instance this CGD report for the estimated return on investment in such a scheme, and this report for the same at the more granular level of EU member states

Use of National Action Plans on AMR

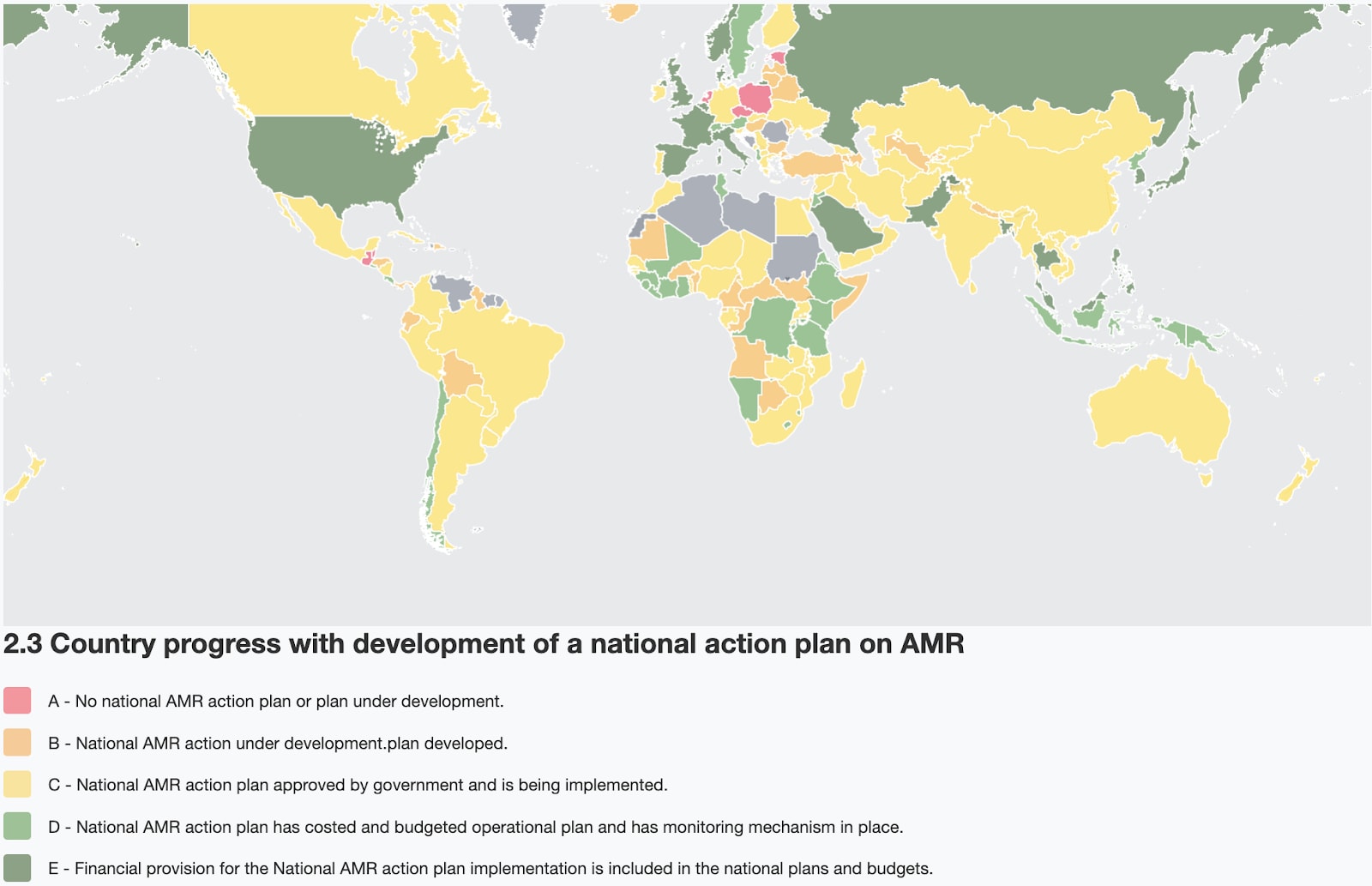

Given the projected growth and changing nature of the AMR burden, it is concerning that in 2023, the WHO Tracking AMR Country Self-Assessment Survey (TrACSS) found that only 71 (40.1%) out of 177 responding countries reported the existence of a monitoring and evaluation plan as part of their their National Action Plan (NAP) on AMR, and only 20 countries (11.3%) reported funding implementation of their NAPs due to limited financial or human resources, insufficient capacity, and varying levels of political support. Additionally, even among the G7 countries many areas still need improvement, from full implementation of infection prevention and control measures to the adoption of WHO access/watch/reserve (AWaRe) classification of antibiotics and more

As of 2023, few countries have reported financial provision for implementing their national AMR action plans (NAPs) in their national plans and budgets, especially in the highest-burden regions, which is concerning given the scale and projected growth of the AMR threat. Image from the WHO Global Database - TrACSS

Conclusion

The worsening effects of AMR will reach all aspects of modern life, threatening food security, increasing the risk of basic operations and cancer treatments and leading to significant excess mortality. This new study shows how it has been a leading health threat for decades, being directly responsible for over 1 million deaths each year since at least 1990, and estimates that with our current trajectory it will get worse into the future. We are starting to see a response from the global health community on this topic and many solutions that would reduce the burden of AMR have been known for decades (such as improvements to infection prevention and control, reducing antimicrobial usage in agriculture, improved antimicrobial stewardship and access and development of novel antimicrobials), however, there is still a significant need for further work and investment in this area and an enhanced response across all sectors.

Executive summary: A new study reveals that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) caused 1.14 million direct deaths globally in 2021, with projections showing a dramatic increase to 1.91 million by 2050 unless significant action is taken.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.