Hi! I’m the founder of a new research and policy organization that’s focused on the opportunity of breakthrough treatments for addiction to end the opiate crisis and save hundreds of thousands of lives each year.

Here’s our brand-new substack, we have a bunch of posts coming soon: Curing Addiction: News, Strategy, and Medical Breakthroughs.

We are a mostly volunteer group of researchers, writers, data scientists, biologists, and more. This group has come together from posts on EA forum and 80,000 Hours. We’re looking for more allies and collaborators, particularly MDs, PhDs, data scientists, graphic designers, and health policy experts. Please be in touch! Email address below.

Our argument: curing addiction should be a global priority

Here’s the core of the argument that we’ll be building over the next few months:

- Alcohol, cigarettes, and opiates kill over 10 million people a year worldwide and we believe the ripple effects of addiction have tremendously negative social consequences, including the drug war, crime, domestic violence, social distrust, and massive losses in productivity and economic growth.

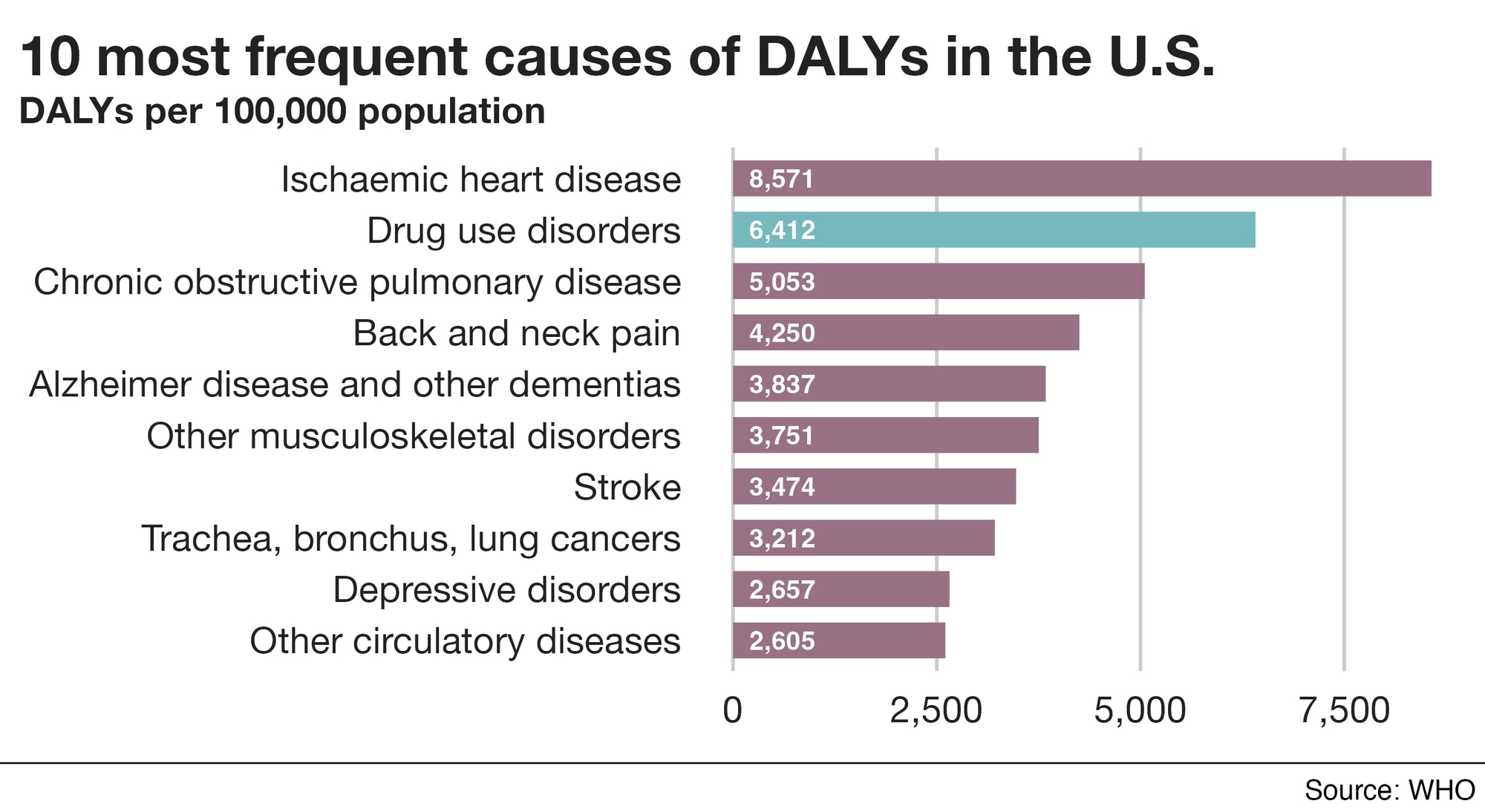

- Drug use disorders are the number 2 source of DALYs in the United States according to the WHO!

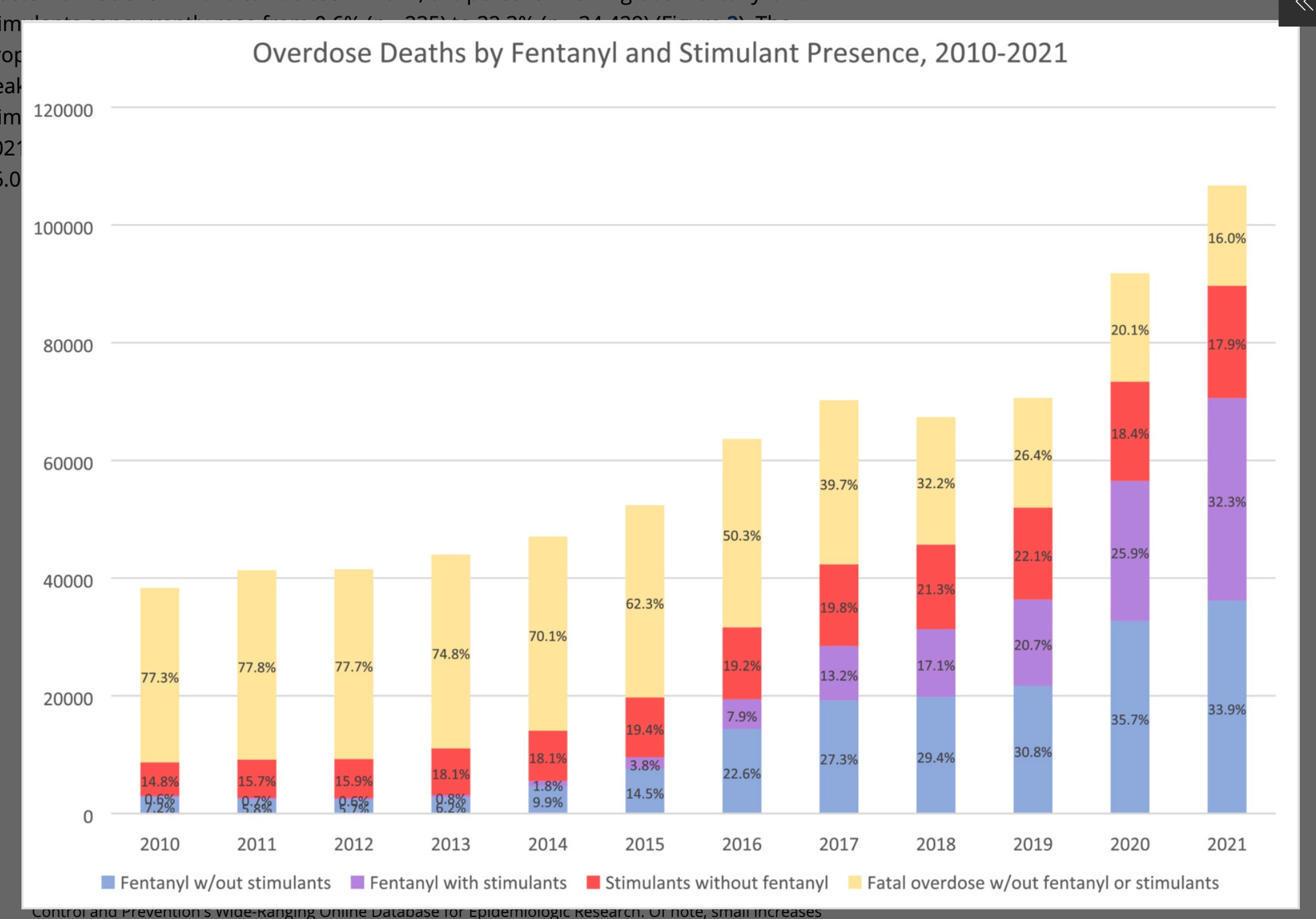

- Fentanyl is extremely easy to smuggle because it is 40X smaller than heroin. It is rapidly spreading worldwide. It is much more likely to cause an accidental overdose because of its potency and combinability with stimulants (see chart below).

- Current drug war and treatment policies are not working nearly well enough, especially in the fentanyl era. Overdose deaths have grown much worse in the past 10 years.

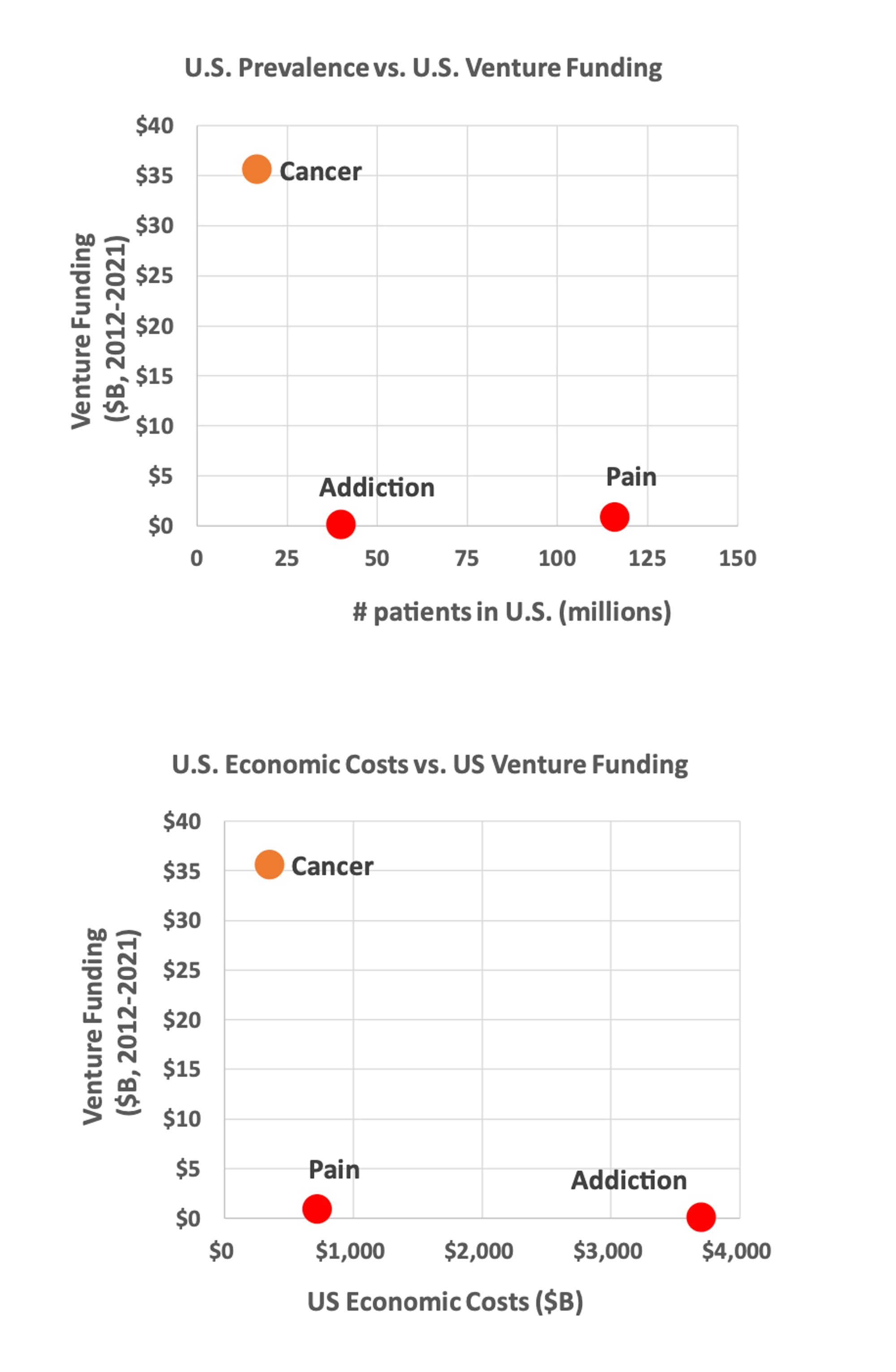

- Opiate addiction alone costs the United States $1.5 trillion a year according to Congress, and yet we only spend $1B on new medication development. There is a tremendous ROI opportunity from investing in better drug addiction treatments.

- Private pharma companies are disincentivized to pursue novel treatments— they doubt the profitability, insurance regulations make it unlikely that they will recoup costs, clinical trials are extremely expensive for brain-related medications, and big pharma is avoidant of trials with unstable populations. This is all fixable through policy changes and incentives.

- Increasing spending on addiction medication development from $1B to $10B a year in the US combined with pharma incentives would have incredible long-term impacts for the whole world, both socially and economically. We can develop real and lasting cures for addiction.

- There are incredible treatments in development, including opiate vaccines, non-addictive painkillers, and especially GLP-1 drugs for reducing addiction to alcohol, cigarettes, and opiates but they all need funding and focus to get through Phase 1, 2, 3 trials. Our post on Curing Addiction is about new GLP-1 research, which may be on the brink of revolutionizing addiction treatment.

- Success with a cure for addiction would benefit the whole world, for generations. We have a chance to effectively end this scourge permanently, as we’ve done for many other diseases.

Policy and market failures

One example of a market failure that we believe is fixable through bipartisan legislation: when a novel non-addictive painkiller is approved in the US, insurance companies and government payers will only pay for the drug if the clinicians can show that cheaper, existing drugs (opiates) are ineffective for the patient. This means that we continue to create new opiate addictions when people receive medical treatment and the massive social costs of these new addictions are pushed onto society as a negative externality by the insurance companies.

How to fix this?

Let’s say a pharma company has a new non-addictive painkiller and they know that sales will be limited because low-cost existing generic painkillers (opiates) will be used as the first-line treatment. The medication itself is cheap to produce but the company needs to charge a high price since use will be so limited. The government also knows this and both the company and the government use standard methods to calculate roughly $400M in expected sales during the drugs patent period. The government can then step in and offer the company, for example, a $500M minimum guarantee in exchange for the company selling the drug at a low cost so that it is available to everyone as a first line therapy. Insurance companies can be required to cover it at this new low cost price. The result is that the company makes more money than they would currently and the government makes a very small investment that prevents thousands of new addictions and has huge ROI for society.

These are the types of policy obstacles we want to identify and address!

Our progress

In just the past few months, we have:

- Brought together a smart and wonderful group of folks to work on this.

- Presented to the policy staff of a US Senator who has been active on opiate legislation.

- Met with doctors, scientists, and clinicians working in hospitals, pharma, and addiction research.

- Interviewed clinicians and service providers working with patients.

- Written several articles that will be published soon on our substack, Curing Addiction (…did I mention that you should subscribe??)

Help we’re looking for

We are looking for people to join our effort:

- MDs and PhDs who have experience in addiction or pain and believe in what we are doing. Even if you are very time limited, you can make a tremendous impact by being available as an advisor or doing calls with us when we speak to policymakers.

- Experts in this field who are interested in working on research and writing projects.

- Data scientists, health policy experts, global health experts, people with experience doing economic modeling and forecasting. Each incidence of addiction has tremendous downstream economic costs so the ROI on preventing or curing addiction is far higher per person than most diseases.

- Outreach, graphic design, coalition building, marketing.

- Excellent writers who understand both science and policy and politics and some level of depth.

Specific types of tasks:

- Science writing for our substack— smart, funny, rationalish, engaging.

- Modeling the health and economic impact of novel addiction and pain medications.

- Outreach to organizations in order to build a coalition to push for legislation.

- Data science, chart creation.

- Party planning….?

We are hoping that you will:

- Follow our work on the substack.

- Be in touch if you want to join the effort.

- Help us find funding to hire a full-time science writer and other research support.

Everyone (like us) loves charts!

We have a whole bunch of fascinating original charts that we’re working on. Meanwhile, here’s three of the most important that we’ve seen recently. These will be featured, along with others, in Chart Packs on our substack.

(Notice how quickly drug combinations have risen because fentantyl is easier to combine than heroin) US Only - Source

Thanks for reading! Please be in touch! addictionpolicyinitiative@gmail.com

Official website and organization branding coming soon…

Thank you so much for writing this! I hope this isn't considered too off topic, but I run the Effective Altruism Addiction Recovery Group which I am maintaining but is still fairly slow at the moment. If you are reading this and are worried about your own addictive behaviors, feel free to join the server, or if you would rather not, feel free to reach out to me directly, and I would be happy to meet/help any way you think will be most useful. You should be able to join through this link:

https://discord.gg/W8sFnNEbdT

On your specific theory of change—Perdue falsely marketed OxyContin as non-addictive, and the FDA, government, doctors, etc lapped up their slow-release coatings & other measures, when they probably should've known that addicts would find ways to break them. This kind of ignorance is, in my eyes, only explainable by their salaries depending on them not thinking about it, for example through industry lobbying.

If your theory of change relies on lobbying, how would you out-gun the pharmaceutical companies? And even if not all pharmaceutical companies are bad actors, how would you tackle the ones that are?

Well the theory of change here actually includes the pharma companies in trying to develop treatments. I don't trust pharma to do anything other than profit maximize, but I think the dynamics are such that this effort won't be in opposition to their interests and the FDA has already clamped down hard on new medications with addictive potential.

The government probably should have put the Sackler settlement money towards development of non-addictive painkillers.

This is a great idea and seems pretty well thought-through; one of the more interesting interventions I've seen proposed on the Forum recently. I don't have any connection to medicine or public policy or etc, but it seems like maybe you'd want to talk to OpenPhil's "Global Health R&D" people, or maybe some of the FDA-reform people including Alex Tabbarok and Scott Alexander?

Thank you, these are very helpful!

Executive summary: A new research and policy organization argues that curing addiction, especially to opiates, should be a global priority and that current market failures and lack of investment are preventing the development of breakthrough treatments that could save lives and have immense social and economic benefits.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.