> How the dismal science can help us end the dismal treatment of farm animals

By Martin Gould

----------------------------------------

Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

----------------------------------------

This year we’ll be sharing a few notes from my colleagues on their areas of expertise. The first is from Martin. I’ll be back next month. - Lewis

In 2024, Denmark announced plans to introduce the world’s first carbon tax on cow, sheep, and pig farming. Climate advocates celebrated, but animal advocates should be much more cautious. When Denmark’s Aarhus municipality tested a similar tax in 2022, beef purchases dropped by 40% while demand for chicken and pork increased.

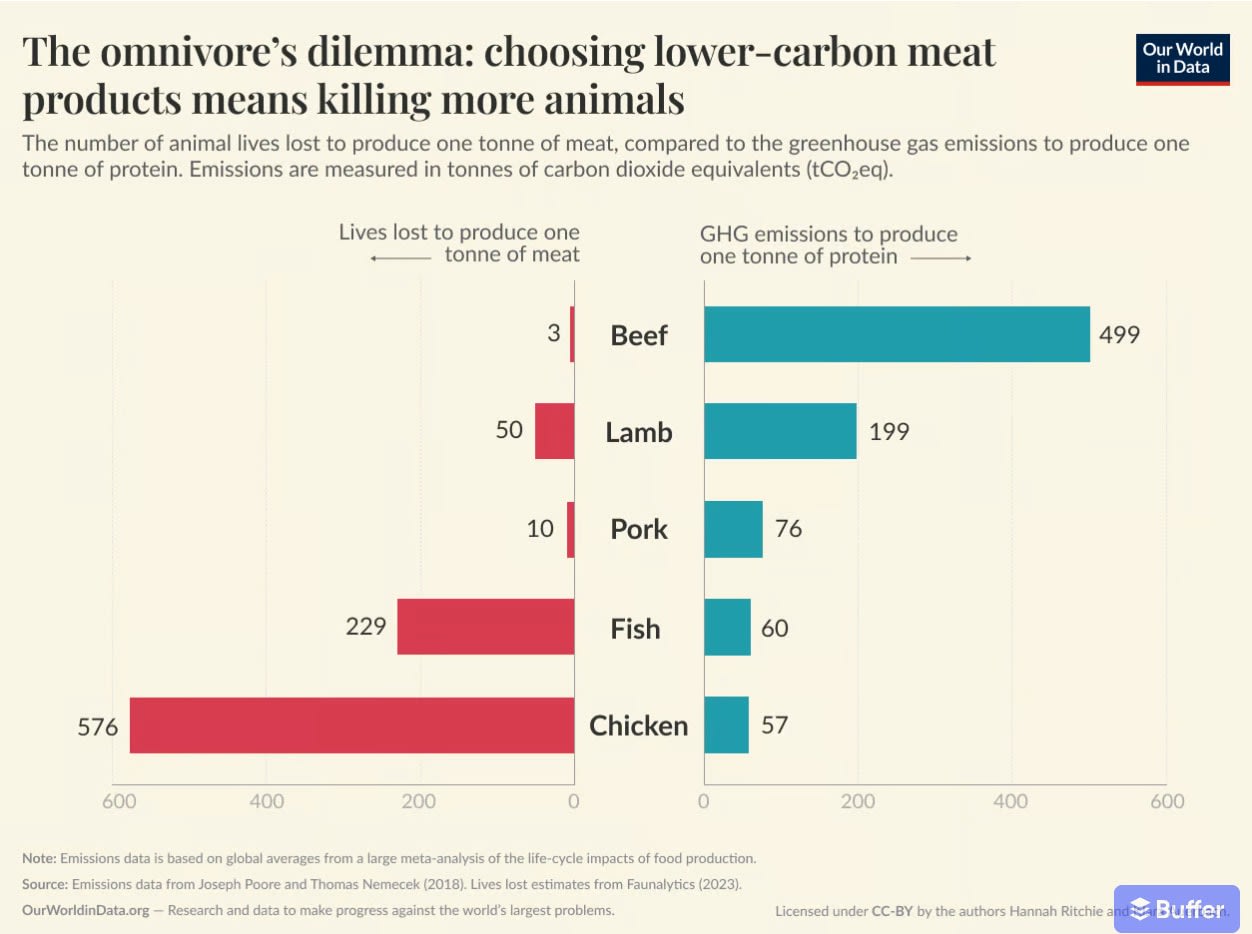

Beef is the most emissions-intensive meat, so carbon taxes hit it hardest — and Denmark’s policies don’t even cover chicken or fish. When the price of beef rises, consumers mostly shift to other meats like chicken. And replacing beef with chicken means more animals suffer in worse conditions — about 190 chickens are needed to match the meat from one cow, and chickens are raised in much worse conditions.

It may be possible to design carbon taxes which avoid this outcome; a recent paper argues that a broad carbon tax would reduce all meat production (although it omits impacts on egg or dairy production). But with cows ten times more emissions-intensive than chicken per kilogram of meat, other governments may follow Denmark’s lead — focusing taxes on the highest emitters while ignoring the welfare implications.

Beef is easily the most emissions-intensive meat, but also requires the fewest animals for a given amount. The graph shows climate emissions per tonne of meat on the right-hand side, and the number of animals needed to produce a kilogram of meat on the left. The fish “lives lost” number varies significantly by

Sorry for the slow response here! Agree that diffusion is an important issue. A few thoughts: