Elected officials control billions of dollars in spending and make policies that affect millions of people. But we choose them through plurality voting, a system that encourages extremism and forces many voters to choose between their favorite candidates and those who actually stand a chance.

In this talk, Aaron Hamlin of the Center for Election Science discusses approval voting, a method that works much better without adding complexity, and how the Center plans to implement it across the country (they’ve already won a landslide victory in Fargo, North Dakota). Aaron also recommends this podcast.

Below is a transcript of Aaron’s talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube or read it on effectivealtruism.org.

Origin story

Elections have vast consequences for everyone, so it's a real shame that we run them so poorly. Why is that?

Let me tell you a story about when I was in graduate school. This was in 2008 — during an election year. I went out to dinner with my friends.

We were talking about whom we were going to vote for, and I noticed something disconcerting: All of my classmates [planned to vote] for people whose ideologies and views didn't align with their own.

This disconnect was really alarming to me. I walked away from that dinner upset.

I kept asking “why” questions: Why was it that my friends were voting against their interests? Why is it that we elect terrible people to office? Why is it that better people don't run? Why are certain candidates marginalized?

These questions led me to the voting booth — and, more specifically, the ballot box.

When you look at the ballot itself within the voting booth, you see directions that say, “Vote for one.” They seem innocent enough. But this has a huge impact. It’s called plurality voting, or first-past-the-post voting. But for the purposes of this talk, I'm going to call it choose-one voting.

Our broken voting system: Why it matters

There are some symptoms of the problems caused by choose-one voting.

We would like our voting method to elect strong, consensus-style winners. Instead, we see polarizing winners. We would like elections to be more inclusive, so that more candidates run. Instead, certain candidates don’t run for fear of not being viable. We use proxy measures for viability, like whether a certain candidate has money or name recognition, but those attributes aren't necessarily good predictors of whether someone will do a good job in office. More inclusivity would also mean that when people bring good ideas to the table, [we could measure and see the amount of support they generate]. Instead, we see ideas marginalized.

So why do we see these outcomes? The voting method that we use encourages us to betray our favorite candidate.

Imagine there's a candidate you like, but you view that candidate as unviable. Instead of choosing them, you choose someone else whom you view as just okay among the frontrunners. You don't actually get to show support for the candidate you like.

Also, since this voting method only allows us to choose one candidate, if we have feelings about other candidates, we don't get to express them.

Finally there's an issue with vote-splitting; if there are multiple candidates who are similar, we can't choose all of them, [which could result in] a split vote between them and another candidate who doesn't have similar candidates running alongside them. Some people say, “We'll just do a runoff,” but that doesn't solve the issue.

We still miss out on that consensus candidate in the center, because the vote gets divided between the left and the right; the candidate in the middle doesn't make it to the runoff. This is true even with ranking methods, such as ranked-choice voting or instant runoff voting, that attempt to simulate sequential runoffs. That candidate in the middle still gets knocked out.

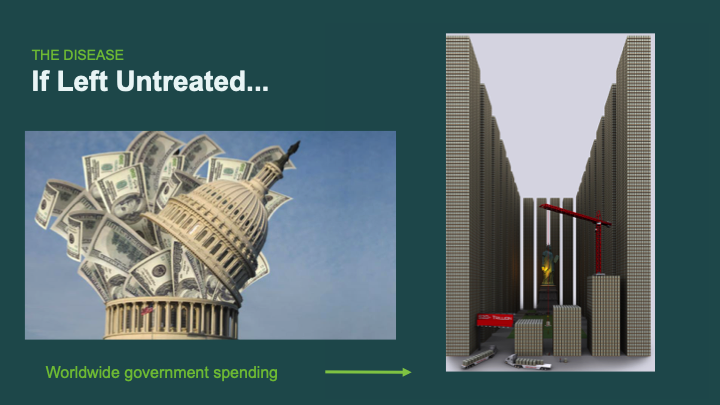

So what happens if this is untreated — what kinds of consequences are there when we use this terrible voting method to elect people into office?

People in office have a lot of responsibility, and one of their responsibilities is to spend avast amount of money. Think about all of the causes that we would like to see prioritized with funding. Worldwide government spending totals over $20 trillion. That’s not an easy number to wrap our heads around, so imagine $100 bills in U.S. currency stacked up to the height of skyscrapers surrounding the Statue of Liberty.

People who are elected do more than just spend money; they also control the policies that govern our day-to-day lives — for example, criminal justice reform policies that determine whether we treat inmates civilly and ensure that they can move back into society, versus policies that keep them in solitary confinement. Consider mental health issues, decisions over sending people to war, bio-safety risks, and animal welfare. Do we allow factory farming to continue? Do we address environmental issues or allow CO2 levels to rise? Do we address AI safety or ignore it?

It’s important to realize that these spending and policy issues happen on a worldwide scale. This map shows all of the places that use either the choose-one voting method or a runoff type of system.

We see the same issues. We see (in green) places that use a ranking method to simulate a runoff election — which, as I mentioned earlier, can lead to a lot of the same issues. So as bad as this map looks, with all of red areas using that crappy voting method [choose-one voting], it’s actually worse because ranking methods aren’t that good either.

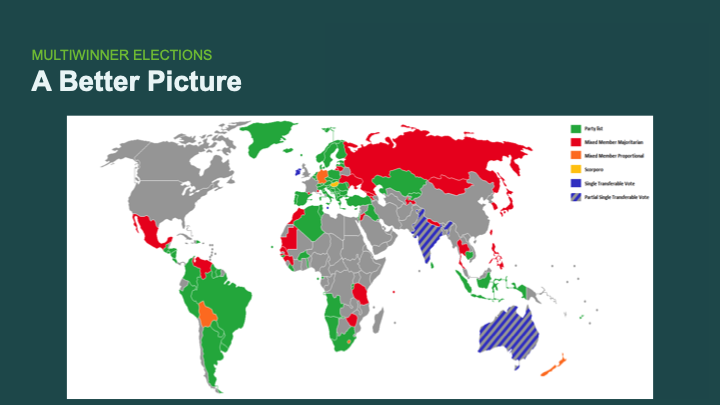

To be a little bit more optimistic: The map we were just looking at showed single-winner methods for executive offices. Here is a map of places that use different types of proportional voting methods.

Proportional methods are a big step up. They address a lot of issues, such as gerrymandering. But it’s also important to get voting for single-winner executive offices right, because these are the people who sign in legislation — and they often tend to be the most powerful lobbyists there are.

Why approval voting?

So what do we do about all of this? We have this terrible voting method — what’s the alternative?

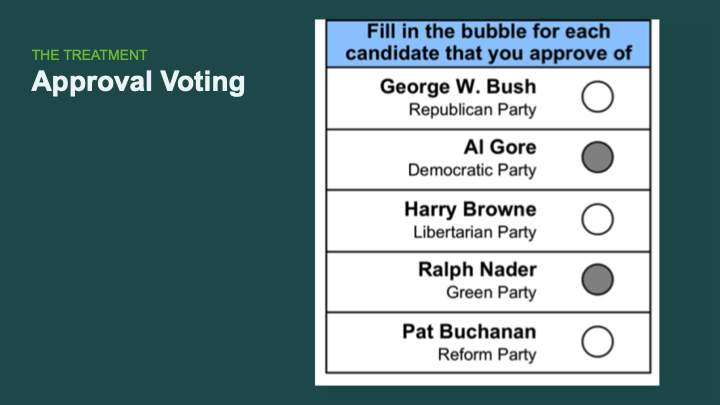

Approval voting is another voting method that allows you to select as many candidates as you want. This is very easy to do. It works on the dumbest of voting machines. You can hand-count it.

It also has some really nice features. Imagine there's a candidate you like, but they're not perceived as very viable. Under approval voting, you can support that candidate — and you can also support one of the frontrunners. You don't have to worry about throwing your vote away. If there are multiple candidates that you like, you can support multiple candidates. If you want to hedge your bets against a candidate that you don't like, you can do that with another candidate — for example, a more moderate compromise candidate.

This voting method also tends to elect more consensus winners. It provides a much more accurate reflection of support for third parties and independents. And it encourages more candidates to run who otherwise wouldn't, because they don't have to worry about the viability issue.

So how does this look in practice? For instance, this is a 2007 French study.

We can see that under choose-one voting, shown in red, there is a different winner compared to approval voting. In this French election, Sarkozy won under the choose-one method and under the runoff method. But Bayrou, a more moderate, consensus-style candidate, would have won under approval voting.

In addition to the winner changing, we see that third parties and independents do much better under approval voting; they receive from five to 10 times as much support. And it's important to note that this is something we consistently see. You can't marginalize candidates or ideas in the same way when they have, for example, 20% support versus 1% support.

You can see the same pattern in the 2009 German election.

The winner didn't — and doesn’t always — change with the voting method. But a voting method has other jobs to do besides just selecting a winner. It's important to gauge support for other candidates. For instance, we can see candidates receiving just a few percentage points of support under choose-one voting. But under approval voting, when their actual support is shown, they receive up to 30% support.

Even if we were using approval voting in this election and those candidates [who received 30% support] didn't win, they would've gotten their ideas heard. They may have even had certain policy issues co-opted by the frontrunner candidates, which can be a big win for candidates who just care about the policy issues.

It's also important to note that some candidates didn't change too much from the choose-one method versus approval voting. And that's because approval voting doesn't magically make you a better candidate. You still have to be a good candidate, even under approval voting. It'll capture your support — but your support actually has to be there.

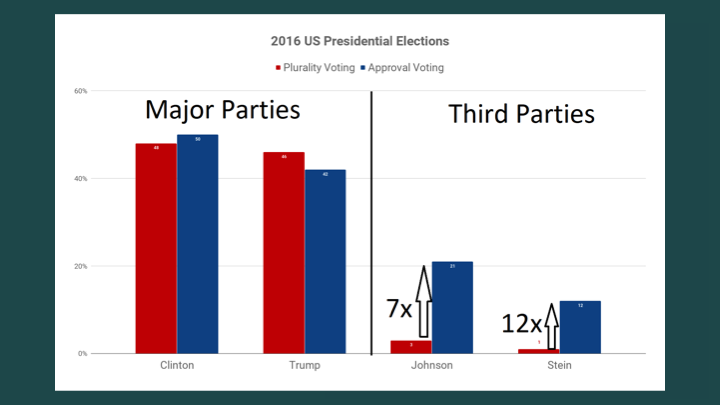

Here's the 2016 U.S. election.

We see that the winner under our choose-one method and approval voting is the same; Clinton wins in both instances. Some of you may be thinking, “I thought Trump won.” That's true, but you have to remember that in the U.S. we managed to take the worst voting method there is [choose-one voting] and make it even worse by nesting it under the Electoral College.

Also, look at the third-party candidates. [Approval voting would have shown more support for] Johnson from the Libertarian party and Stein from the Green party. This is a feature that we see time and again under approval voting — that more accurate reflection of support for third parties and independents. Stein goes from 1% to 12%, and Johnson goes from 3% to 21%. These are candidates who were completely excluded from every single debate because of the [seemingly] small amount of support that they had. That doesn't have to be the case with approval voting.

Also, in 2016, Gallup conducted a poll asking people if they knew who in the world these [third-party] candidates were. Two-thirds of people didn't, because these candidates were getting marginalized in the media. Imagine the positive reinforcement loop that would allow them and other candidates to receive more attention [under approval voting]. Remember: Under our current voting method, this can cause candidates not to run. That was the case in 2016 when Bloomberg decided not to run. Surely there were other strong candidates who also decided not to run, because they either didn't want to split the vote or didn't perceive themselves as being viable.

So how does this much better alternative [approval voting] work in practice? How do we change our current system?

Fargo: the first win for approval voting

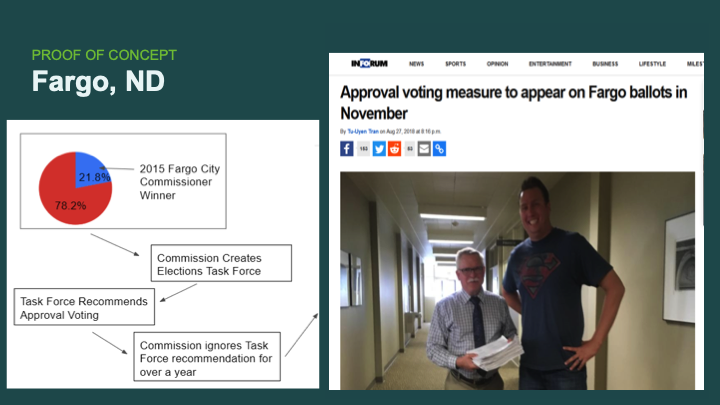

I have another story for you. This is a story of Fargo, North Dakota.

North Dakota had an interesting election in 2015. It was a five-way race in which the winner had 22% of the vote. This was, frankly, embarrassing for the City Commission. So they created a task force. One of the task force members was particularly zealous about this issue, had done their homework about approval voting, and reached out to us.

We talked and he recognized that approval voting was going to be a strong solution for Fargo. He took it back to the task force. The task force got on board, presented it to the commission, and recommended approval voting for Fargo. And do you know what the commission did after the task force had recommended approval voting? It ignored the task force for an entire year! But that did not sit well with this particular member of the task force. He gathered enough signatures to put approval voting on the ballot itself, which had never been done before.

We won. So Fargo, North Dakota became the first city ever in the U.S. to implement approval voting. And we won by a lot: 63.5%. We won in every single precinct in the city of Fargo.

What's next?

How do we replicate this?

There are certain things that we look for:

* Local support from the community. In the case of Fargo, we had a member from the community reach out to us who was also well-connected.

* Single-winner elections. In Fargo, we focused on the mayoral election.

* Cities with control over their own voting method. That was the case in Fargo because North Dakota is a home rule state.

* Ballot initiatives. We have to use them.

You may be wondering why was the Fargo commission didn't listen to the task force. One of the people on that commission was the same person who won with 22% of the vote. And he was not very excited to change the voting method that allowed him to slide into office.

Right now we have this situation where we are using the worst voting method there is to elect people to office, who then choose how we spend our immense amounts of taxpayer dollars and which policies govern not just our lives, but the lives of animals and other sentient beings who experience suffering.

But this is a solvable issue, as we showed in Fargo (which has a population of 120,000 people).

This is also scalable, as we'll show next year in the city of St. Louis, which has a population of over 300,000.

And this is replicable, as we'll show in other cities and states in the future — and not just in the United States, but across the globe.

It's important to remember, too, that unless we have the resources to push this forward, we will continue to use this awful voting method to elect people to office who make incredibly important decisions about the spending and policies that control not just the lives of people who exist today, but the lives of many more in the future.

I'm not here to say that this is a silver bullet. But approval voting is one of the most impactful interventions that we have the power to achieve. Thank you.

Q&A

Moderator: Thanks very much for that, Aaron. What is the biggest pushback you get [when promoting approval voting]? Is it just inertia? Status-quo incumbents?

Aaron: We just circumvent that by not asking them. We do a ballot initiative instead. But in terms of barriers, there's not much pushback from members of the community. Funding is the main issue that holds us back. Ballot initiatives are very expensive to run.

Moderator: How can people act on that? Where would they donate?

Aaron: The Center for Election Science. Our website is electionscience.org. Also, we communicate about other partners that we work with and provide opportunities to donate to our partners directly.

Moderator: Have you seen other examples outside of the U.S. of approval voting working well?

Aaron: Right now we're focused on the U.S. Fargo is the only city in the entire world that has implemented approval voting, so we are real trailblazers in this area.

Moderator: Could you expand on why ranked-choice voting is not a good solution for the problems that you've laid out?

Aaron: Approval voting is nice because it has very low complexity costs. It's very easy to implement and it does a great job of electing strong winners. It captures support even for people who don't run. And it has a low barrier to entry for people who are looking to run.

Ranked-choice voting is much more complicated. Whoever has more than half of the first-choice votes wins. If someone doesn’t receive more than half of the first-ranked votes, you look to the person with the fewest first-choice votes. You eliminate them and transfer the next-preference votes [of people who preferred the eliminated candidate] to the appropriate candidate. Then you add up all the votes again, and if anyone has more than half of the first-choice preferences, you have a winner. If not, you repeat that process again. It’s complicated. With approval voting, you just choose as many as you want. And most of the time, you don't have to worry about retrofitting the voting machines.

Also, with ranked-choice voting, like I mentioned before, you must contend with the center-squeeze effect. You can have a very clear strong winner and not elect that winner. There are also scenarios with ranked-choice voting in which you can honestly support your favorite candidate and end up with a worse outcome. And for third parties and independents, the ranked-choice voting algorithm doesn't do a good job at showing all of the data concurrently; it only considers a portion of the data at any one point. That can result in a poor picture of the support of third parties and independents. With approval voting, in addition to using a simple algorithm of just addition, you can also see all the data at the same time. That means that you see all the support for third parties and independents.

Moderator: And is there any sort of rigorous study of how hard or easy voters find it to understand approval voting compared to other methods? Intuitively it's very compelling, but have there been any studies?

Aaron: There haven’t been any studies explicitly comparing understandability. But in terms of education campaigns and partners that we’ve spoken to, the simplicity of approval voting has a really big impact compared to ranked-choice voting.

There are different ways to measure complexity. Perhaps one proxy measure would be how long it takes to explain approval voting versus ranked-choice voting. That could go a long way in studying [ease of understanding].

Moderator: What do you think of attempting a statewide change of the choose-one method in a state such as Maine? Or do you feel city-level change is the best place to start?

Aaron: I think state-level change is important and we will certainly move up to that. Our strategy overall has been to show a proof of concept, which we are doing in Fargo. Then, we will scale and replicate, as we’re doing in St. Louis.

The next target will be even larger — a population of over half a million. And then we'll be able to look at state-level change. We have to create a track record before reaching the state level.

Moderator: What is your timeline for making that progress?

Aaron: Again, we're largely funding-constrained. If the funds are there, we can move very quickly. At the end of 2017 we received a grant from the Open Philanthropy Project. And within less than a year of receiving that grant, we made Fargo happen. So we're very quick and we're very efficient with the funds.

Moderator: Great. And how big is the organization currently?

Aaron: Our fourth hire will be starting soon.

Moderator: What do you think of the viability of the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact?

Aaron: It's a way of using an interstate compact or an agreement between states [award their electoral college votes to the candidate who wins the] national popular vote. I don't think it’s worth celebrating too much. It’s [an improvement] — for instance, it would have resulted in electing Clinton in the 2016 election. So it can be material in terms of the outcome.

But we have to remember that even [with the interstate compact] we're still using the worst voting method.

One nice component of approval voting is that it can interact with the interstate compact, which means that it has features like precinct mobility, which ranked-choice voting does not have. Also, you can tabulate results with discordant states that aren't using approval voting; you can choose data from other states and add it to approval-voting data, but you can't add ranking data and choose-one data at the same time.

Moderator: Great. Please join me in thanking Aaron.