I’m in graduate school now (MPH @ Harvard), after 6 years working with a small start-up non-profit organization in India. Recently at EAG Boston, I did 1-1s with some of the smartest young people I’ve met - a sizable number finishing up college or a year/two out of college. I found myself repeating a few points of advice, and that’s usually a good cue that I should be writing them down. While folks well into their career often do a fantastic job of offering wise, usually far more well-considered advice, I believe there’s value in listening to people just a few years ahead of you. They are far more likely to remember their mistakes more accurately, and attempts to rectify them seem more relatable.

Why is this on the EA forum? EAG Boston helped me see how effective college-based EA chapters have been in inspiring younger people to participate in the movement. There’s so much energy and an even greater pressure on oneself to grow as quickly as one can. While there’s sufficient discourse on what’s worth doing, I want to see more of how to do the work.

About me: Currently, I’m a public health graduate student studying health and social behavior. Prior to this, I helped build an accelerator for founders of small, under-resourced childcare institutions to support them in integrating evidence-based practices in childcare and effective ways of their non-profit organizations. Doing this work forced me to learn ways of managing my own motivations, skills, and tantrums in a small, high-agency team! It was not a low-pressure way to learn, but I wouldn’t trade these experiences for anything else (maybe more money)

So you’ve done well in school - here’s how work can suck less for you:

Epistemic status: Slightly provocative, emerging hypotheses, rant-heavy

- Please don’t jump into grad school immediately! Grad school makes so much more sense when you’ve worked for a few years. You contribute more to classroom discussions, and your ability to call bullshit is greatly enhanced by existing in the professional world. I understand that a number of really smart, mostly econ-pilled EA-aligned folks want to jump into a PhD or an MPP, but if there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be this. Your ability to make the best use of the incredible breadth of resources in grad school is so much more enhanced by knowing what you like, knowing what you’re good at, and, most importantly, knowing what’s useful out in the real world. Development contexts are so complex; people are driven by explicit/implicit incentives, and working hard at important problems involves judgment about what’s important!

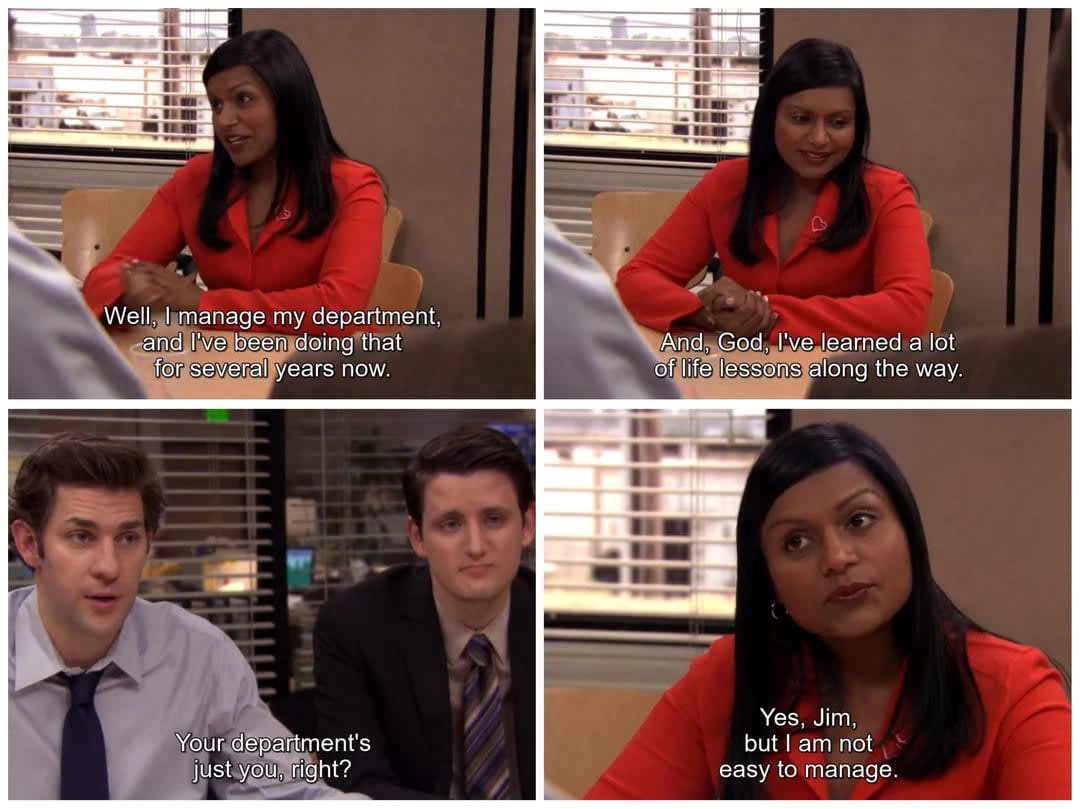

- School is a pretty shitty training ground for real work. It’s highly likely that if you’ve consistently done well in tests, you are just really good at testing - you know what is being tested, you know the value of practice tests/previous year papers, you’re pretty aware of what you should be focusing on for the exams, and you’re able to do it in a relatively short period of time before your test. As a solidly good test-taker, I know how good this feels. It’s also a poor template for work because you need to show up every day. You’re often working towards multiple projects with results that are likely to show up 6 months or a year or two from the day you put in the work.

- It took me two years to learn how to show up consistently with as much energy and enthusiasm as I could muster. It was insanely long, and I wish I had worked on it more pointedly when I started!

- I treat my life as a series of projects, so the only thing that has worked for me is to break each massive project into smaller goals with tight timelines and super tight feedback loops about success, quality checks, and places of improvement

- Talk to your manager about this! They’re usually happy to help you figure out how to show up better for work.

- Experiment liberally - if your work is flexible and largely independently driven, attempt to use different productivity tools. I owe my life to focusmate, but I don’t need it as much anymore! Productivity is seasonal, and what’s important is that you record notes from this experience so you’re not starting from scratch each time you try to figure out how to get out of a rut.

- On the point of note-taking, I would also highly recommend keeping track of the feedback you receive. Literally, write it down. Why is that? It’s usually incredibly useful to make your mistakes so you can learn from them. But most people overestimate their ability to remember these learnings.

- For the better part of two and a half years, I maintained a document with the feedback I had received from my manager/ other mentors. The personal blends with the professional, so I would also reflect on therapy in the same document. This document played a crucial role in helping me avoid mistakes I had already made.

- By being able to learn from mistakes when I wasn’t so emotionally invested in the situation, I was able to build a much more realistic, detailed model of how I mess up, and why it matters. This allowed me to advocate for changes with myself with much more conviction.

I made it a point to read the advice whenever I received new feedback.

On April 19, 2022: “Repeated breaches in contract/lack of ownership affect how long a rope I’m given- more micro-management and fewer opportunities to step up”

- To give you some context to this entry, integrity is at the core of everything you build. I struggled with this; I still struggle with this. You must stay true to your commitments and be transparent when you cannot. Trust breaches are incredibly hard to bridge, for trust is earned through repeated action over extended periods of time. Operating in a trust deficit sucks. I can guarantee you that it’s far worse than acknowledging that you blundered and offering to clean up the mess

- Know your triggers. For me, when my manager asks me 5 questions in succession, I feel like I’m being put on the spot. I feel like I’m back in the classroom, and my teacher is upset with me for not knowing the answer. So, I instinctively fudge the truth of the matter to come off better than I would with a full, honest answer. It’s mostly not even a conscious decision. Once I identified this trigger, I told my manager about it. I told him that I would prefer to have these questions over email/text - so I feel less pressure. Being put on the spot is not something I can avoid forever, and I need to work through this, but it was helpful to discuss solutions with my manager.

- I’m also aware that what probably helped the most was going through this experience - but I would highly recommend learning from my mistake instead of dealing with this one on your own

- Excerpt from my feedback document about this conversation with my manager: “You have this impatient look and sigh that makes it very hard to say “repeat”; and it always makes me more conscious and likely to jump at answers instead of thinking them through. I’m letting you know that so I can consciously take more time”

What’s crucial when you find out these patterns about yourself in work, is you have to remember these narratives about how you’re wired are not set in stone. Be kind to these patterns because these patterns have served you well. Don’t feel compelled to change them all at once because how you’re wired is valuable! My obsession with being perceived as smart makes it that much more likely that I would prepare for a meeting well in advance. Intentions are useful to analyze, but some actions are independently good, despite these intentions. When you do decide that some of these patterns don’t serve you well anymore, know that you can gently put them down. You can effectively reframe how you operate, acknowledging that narratives about your previous work do not need to hold true anymore.

An entry from my feedback doc: “You’ve got to stand up for yourself when you feel like you and your work are being misinterpreted. It’s the only way you’re going to be able to break existing narratives that are pulling you down. You need to be able to call it out if you feel like someone’s belief/understanding of you and your work differs from how you see it. “

Know that this will be a slow change that requires consistent expression of the change and a willingness to make things uncomfortable when you feel like people are still holding older stories of you that aren’t true anymore. You have to give people the grace to get it wrong, but you don’t have to stay silent about it. Conversely, It’s more likely you’ll stick to it if you repeat this new commitment to yourself in public a few times.

Thanks for your openness. Not an easy thing to do but gives a lot value to the reader.

Also great advice

Appreciate it! Thanks

Executive summary: Transitioning from school to work requires specific strategies and mindset shifts, including consistent work habits, careful feedback tracking, and self-awareness of triggers and patterns.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Strong +1 agreement to all points

Glad you found it interesting!