Thank you

At EAGx Amsterdam, I shared most of this as a talk. I was afraid I'd run out of time, so I decided to do things backwards and start with the thank you. I did not want to miss the most important thing. Since I might lose you halfway reading this long and personal piece, I decided to keep this order.

The EA community creates a space that makes it easier to donate and to live my values—and to be okay with living in this world. It normalizes caring about effectiveness and spreadsheets, provides frameworks and research and feedback. This community makes me feel less alone in trying to navigate the absurdity and burden of existence.

My Story, Not Yours

I am assuming that anything I do is determined by luck and circumstance, nature and nurture. Therefore, one way to explain why I donate is to show you some of those things. This is personal; my story might not be applicable or relatable to you. I’m not sure there’s anything practical you can learn from it. But maybe my experience raises questions that help you in your giving journey.

First I’ll tell you about my life, with a little context about the state of the world during that time—all pulled from Our World in Data of course. Then, I will tell you why I donate to help others, and why I donate to help myself. I'll end with how I actually donate.

My life

In 1958, twenty years before I was born, life expectancy was 51.6 years. Net enrollment rate in primary education was about 65%.

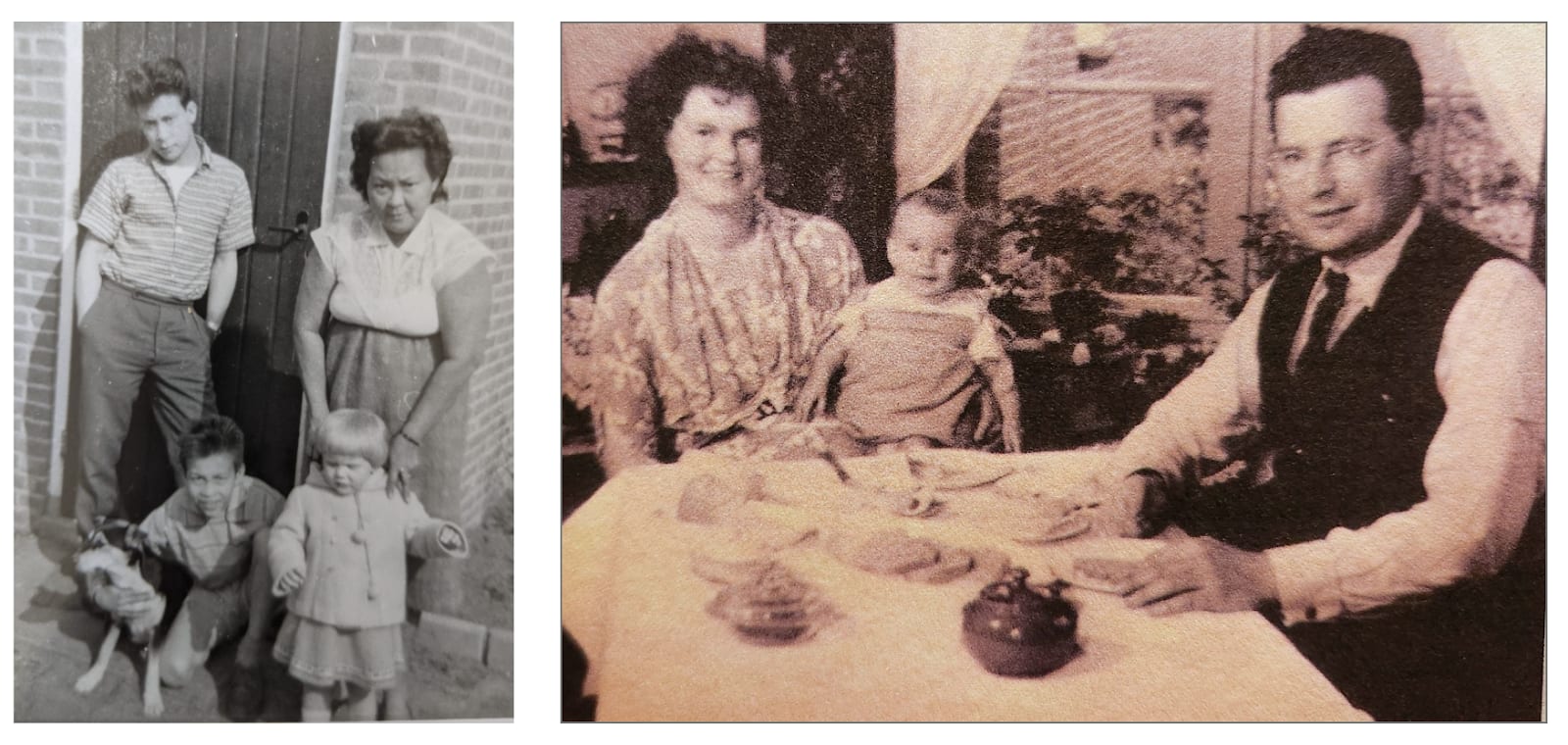

My father, in the photo on the left with the dog, was born in 1948 in Surabaya, Indonesia. A product of Dutch colonialism, he was forced to flee to the Netherlands when he was 7. His mother’s and his own trauma and disadvantages affected him and prevented him from getting the education and opportunities most Dutch kids had. But he did go to school. My mother, the infant on the right, was born in 1950 in Groningen, a smaller city in the northeast of the Netherlands, into a working-class family. This photo was a special occasion. They were able to buy a small home while she was young.

In 1978, the year I was born, approximately 15% of children worldwide died before reaching their fifth birthday. The life expectancy in Cambodia that year was 11.6 years (that shocking number is due to genocide and war).

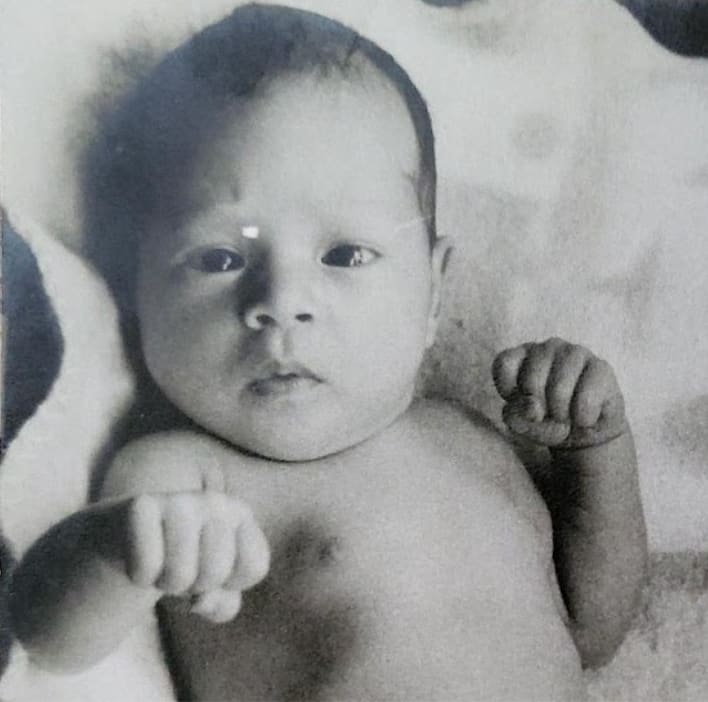

This is me. Like my mother, I was born in Groningen. A few years after my birth, my parents amicably separated. I lived with both of them. We lived in social housing. I was healthy, we had little money by Dutch standards, I did well in school. My mother entered university, the first in her family.

In 1988, worldwide 714,549 people died of measles. 29 billion land animals were slaughtered for meat.

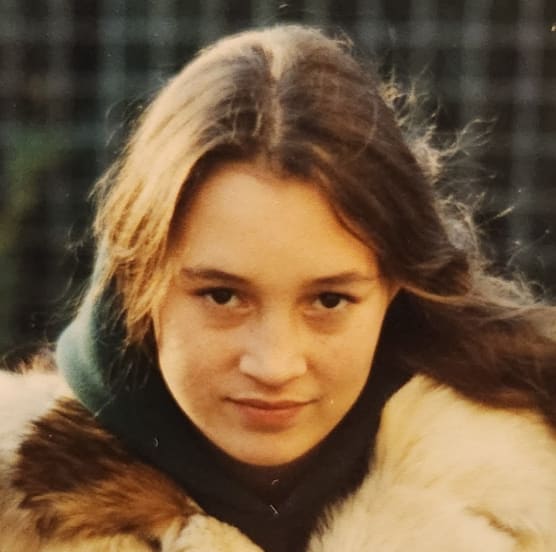

This is me, ten years old, at the zoo. I loved animals. This was the decade when I understood that the world wasn’t fair and full of horrors. I worried about war and I remember watching starving children on the news during the famine in Sudan. In my teens I empathized with James Bond villains who wanted to destroy the earth. I was a button-pusher before I knew what that was.

In 1998, approximately 37.9% of people on earth experienced extreme poverty. More than 42 billion land animals were slaughtered for meat.

This was the last year I still wore the second-hand fur coat I’d bought during my contrarian years to show the meat eaters their inconsistent behavior. My twenties were the period of my life when depression became more serious. I coped through self-medicating and travel and not going to my university classes. And I then got over it through working and falling in love.

In 2008, the estimated number of suicides per 100,000 people was 11.3 (~773,000 deaths). More than 60 billion animals were slaughtered for meat.

At 30, I still believed I cared about animals, without realizing I didn’t in practice. I migrated to the US, just as the economy crashed, but after eight months my partner found a job in Chicago. Half a year later, I was lucky enough to find a decent enough non-profit job—even without a college diploma. I realized that I had to do meaningful things to feel good about myself, and that I needed challenges too. (For years, my resume had a line saying “challenges engage me” without realizing it was true.) I had become the happiest person I knew, but I also had a nagging sense I “wasn’t doing enough”.

In 2018, the world average self-reported life satisfaction was 5.2 out of 10. 78 billion animals were slaughtered for meat.

At 40, effective altruism finally sank in. It felt devastating at first to know how much I might’ve done had I known better. But I started bringing my actions in line with my values, learning how to do good better, going vegan, and leveraging my career capital by sharing my experience. This photo is me actually caring about animals, teaching a fundraising training at an animal advocacy conference.

In 2025, 10.1% of people, roughly 828 million people globally, are still living in extreme poverty. Under-5 mortality in 2023 was 3.6% compared to the 15% when I was born. That’s great, but that’s still approximately 9.6 million parents who lost a young child. And that number looks to be going up this year. And there’s famine again in Sudan. More than 85 billion land animals were slaughtered.

Currently, and likely still in 2028 when I turn 50, I lead Animal Charity Evaluators, the hardest and best job I’ve had. The one where I have done the most for others. I also have a partner who makes good money. By now, I am rich. I feel fortunate in many ways, but the How Rich Am I calculator also tells me I'm in the 99.9% globally. The only meaningful burden in my life is the suffering of others. And this is where we get to the function of donating in my life. And no more gratuitous pictures of myself.

I donate because it helps others

The most important reason to give is that others are suffering. I feel responsible to do good when I can. I also feel like I should do good responsibly—and help as much as I can.

It’s my responsibility to do something

You will know Peter Singer's story of the child in the pond. I should ruin my expensive vegan leather boots to save a drowning kid in front of me. And I should probably not replace them (even though I could and they look quite decent on me) and instead buy cheaper shoes and donate that money to help more children. A preventable death matters equally whether it happens in front of me or to someone’s toddler thousands of miles away. Suffering sucks here and there. It doesn’t matter if I can see it. It doesn’t matter what caused it. It’s only relevant that I solve it, when I can.

And when I hear my neighbor abuse their dog, I cannot be a bystander. When I witness bullying and do nothing, I feel complicit. And I’m not a passive observer to factory farming—even as a vegan I am a participant in a system that creates and maintains abuse on a massive scale. I am not comfortable turning a blind eye when a simple donation supports efforts to end factory farming and improves the lives of animals confined in industrial agriculture.

I should do good responsibly

The urgency and importance are immense, but available resources aren’t. As such, I must triage and give effectively. If I can do something for more individuals with the same amount of effort, I should try. I must carefully examine my charitable choices. So, I pay attention to scope. And sometimes my donations go to things that don’t particularly move me emotionally. Because I have limited money, I help unattractive animals like fishes instead of orangutans. (No offense to the fishes but I find them a little creepy.)

Trade-offs must be made. And that must happen thoughtfully—impartial and with kindness, helping others regardless of how much I have in common with them, what causes their suffering, or where they live. Otherwise, individuals I could have helped might be left to suffer. That seems like neglect to me.

I donate because it helps me

The most important reason to give is that it helps others, but the most compelling one for me, is that it helps me.

Retail Therapy < Donation Therapy < Effective Giving

Life isn't fair and I am uncomfortable with my distribution of luck. I was born in a wealthy nation to resilient, loving, open-minded, clever parents. As you saw, growing up, I never worried about clean water, medical care, or whether I'd eat dinner. I had access to excellent education. I'm able-bodied. I am safe and free. I am a human. I won the birth lottery.

Billions weren't so fortunate. Through sheer randomness, they face barriers I'll never encounter.

Donating doesn't erase my discomfort. But it makes it bearable. It transforms misplaced guilt. I can't fix that I was born lucky, but I can use my circumstances to shift the balance.

My grip on life is rather loose. Life, to me, often feels absurd, exhausting, overwhelming. The scale of suffering in the world—human and animal—I feel it. What keeps me going is usefulness. Being helpful. Knowing that my existence makes things better for others. In a way, my altruism is quite selfish; it gives me a reason to keep showing up.

Effective giving amplifies this. Effective giving gives me the confidence that I am as useful as I can be. That my existence is relevant. I used to agonize: Am I doing enough? Effective giving provides a framework. I now have indicators and experts to tell me if I’m on the right track. I don't have to second-guess every donation. I can trust that my giving is doing genuine good, at scale—not just making me feel good. That distinction matters for my peace of mind.

(Maybe we’re all warm-glow givers, I just need something else to feel that charitable glow than some others?)

Convenience of effective giving

I’m slowly entering perimenopause and I feel one of the common symptoms: I don’t have the hormones to make an effort to care about some of the things I used to. I can't be bothered anymore to think of thoughtful gifts. Honestly? Gift-giving is tiresome. It's a lot of cognitive and emotional labor for something that often ends up unused. So I mostly stopped. Birthdays, holidays, weddings—I give donations. This isn't virtuous; it's efficient.

And I have never wanted to see and do things that are emotionally hard. I am not strong enough to sustainably work directly with animals or people who suffer. It would be too hard. I'd burn out and become useless. Donating lets me help without destroying myself in the process.

Besides being lazy and selfish, I am not the smartest. I am not qualified to do in-depth research into how I do the most good on the margin. I don't have time to evaluate every charity's cost-effectiveness, analyze their Theory of Change, estimate their counterfactual impact, or determine their room for more funding. That's specialized work requiring expertise I don't have. So I outsource it to expert evaluators. I increase my own value as a human and my cost-effectiveness through high-impact giving.

This is how I can live the lives I won't get to live

My job leading an organization is fulfilling and impactful, but not infrequently I wish I was a researcher, an activist, a philosopher, a legislator. These paths called to me at various points. I still feel their pull.

But it does not make sense to try to excel in those roles. I made life choices that put me on other paths. I won't conduct research on how to measure wellbeing. I won't draft legislation protecting us from nuclear war. I won’t mobilize animal activist campaigns. I won't write the philosophical treatise that shifts moral consideration.

Through donating, though, I can associate myself with these dreams of what could have been. When I support the people who do this work—in a distant, intangible way—I can fancy myself as part of those worlds. I can allow others to do the work I imagined for myself.

It's vicarious. It's indirect. It's not the same. But it connects me to those unlived lives—and still have some of the impact I could have had.

How I Donate

I'm far from a saint or martyr. I do things I’m embarrassed to tell you about. I own nice, new things (like those vegan leather boots). Sometimes I travel business class. I work out at the gym I like, not the one cheap one further away. I have a very comfortable home. I tied fancy vacations to work travel—I saw Mickey Mouse and a bushbaby in their respective natural habitats this year.

I wish I was a person who did not do these things, who lived a purer life. I am imperfect. But, I am doing more good than I used to, while maintaining a sustainable, fulfilling life—and I’m trying to be better.

Here's what I actually do

My partner and I have donated ~28% of our gross income in 2025 to high-impact interventions. When I say “my partner and I”, it really is mostly him. He makes a lot more money than I do. The majority went to ACE, our Recommended Charities, and our Movement Grants. We did give to humans too—like to HLI’s recommended charities, and to GiveWell’s top charities fund.

We’ve done some community and warm-glow giving in addition. Family fun-runs, friends in need, local aid and organizing, and I probably misinformed you earlier, besides fishes we might also still help a few orangutans (they remind me of my father).

Professionally, my job is dedicated to helping people help more animals through philanthropy. Prior to this, I worked pro-bono for about four years, helping organizations in the EA and EAA space. Now, I work roughly twice as many hours per week as I'm paid for (because I prefer to, not because it's expected).

Then there are small daily choices. I rarely reimburse all my travel expenses I make for ACE. Though usually this is because I have the privilege to not be bothered—that admin is such a hassle. And as mentioned previously, more out of laziness than dedication, I’ve given donations as birthday, wedding, and holiday gifts this year.

What I do might not be what you can do

But if you’re reading this, you can donate something to others and make their lives meaningfully better in ways that are hard to imagine.

For most of my life, I have not done these things. I grew into this gradually. And my situation might change—my resources and abilities might shift in the coming years, and I will adjust accordingly. But giving effectively will always be part of me. It reduces my recovery time after witnessing suffering and it makes my life more aligned with how I want to exist in this unfair world.

Find your Why

Why I do the things I do might not keep you going. I hope you find your motivation, whatever it is—status, the afterlife, gamify it—I don’t care, but I hope you hold on to it and give. You are needed.

On AI usage: Claude helped me come up with stats about the world in the decades of my life. I then verified them on Our World in Data. Claude also revised my first draft which I then heavily edited again. I don’t think you need three paragraphs explaining the child in the pond. (All those em-dashes are actually mine; I can’t help but like those little stripes.)

(The preview photo of this post is of my desk. The painting used on the forum for Why I donate week I’ve had in postcard form since I was a teenager!)

Thank you for sharing this, Stien. I’m grateful for your candor.

This is such a thoughtful and unique post. I love how you weave together your personal story, history, statistics, and the rise of animal agriculture. It adds so much depth and context.

I especially resonated with the line, “Through donating, though, I can associate myself with these dreams of what could have been.” That completely captures how I feel about giving as well, and it’s one of the main reasons I became a career coach (and why I now work with students!) – you can’t do everything yourself, but you can help others pursue the paths you might have taken.

Beautiful post. I especially enjoyed the personal images and wish more EA Forum posts did that.

Thanks for writing this, Stien. It's inspiring for me personally, and I'm sure it will also inspire others to find their why and give effectively to help.

The way you wrote it and expressed the emotions. I loved it!!!

Executive summary: This reflective personal essay argues that donating effectively is both a moral response to vast, preventable suffering and a practical way for the author to live with meaning, responsibility, and psychological sustainability in an unequal world.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

I really appreciated your post.

It's incredible how much the world has changed since our parents were young—I've thought about that a fair amount in recent years. I think when I was ~15, I thought that in several years I'd have learned most of what I needed to know about being an adult in the world. But the world continued to change. A lot.

Your post & Eleanor's recent GWWC video reminded me that I am helping animals each month through my donations, even when I don't feel optimal at work. I'm one more person in the world doing what I can.

I loved the "personal story x Our World in Data" - well written!

Thanks for writing this post, Stien. I really appreciate your vulnerability and perspectives - they were thought-provoking and inspiring. I can do more to help others.