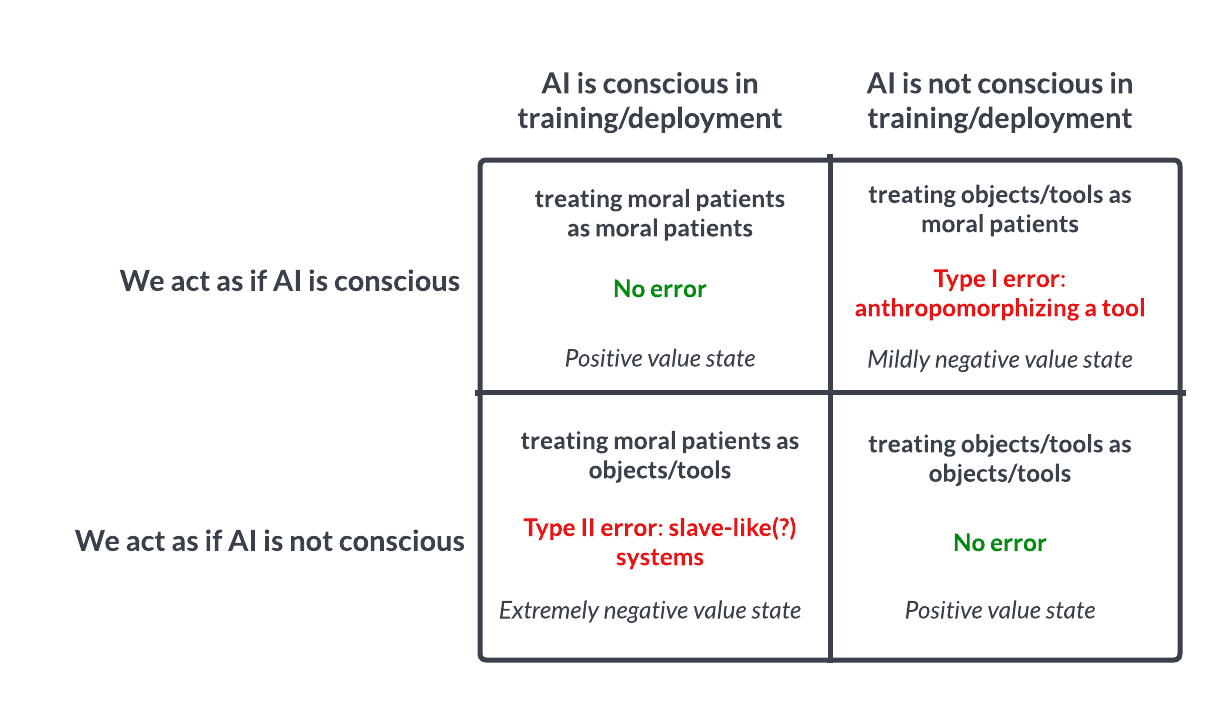

Recently, we shared our general model of the AI-sentience-possibility-space:

If this model is remotely accurate, then the core problem seems to be that no one currently understands what robustly predicts whether a system is conscious—and that we therefore also do not know with any reasonable degree of confidence which of the four quadrants we are in, now or in the near future.

This deep uncertainty seems unacceptably reckless from an s-risk perspective for fairly obvious reasons—but is also potentially quite dangerous from the point of view of alignment/x-risk. We briefly sketch out the x-risk arguments below.

Ignoring the question of AI sentience is a great way to make a sentient AI hate us

One plausible (and seemingly neglected) reason why advanced AI may naturally adopt actively hostile views towards humanity is if these systems come to believe that we never bothered to check in any rigorous way whether training or deploying these systems was subjectively very bad for these systems (especially if those systems were in fact suffering during training and/or deployment).

Note that humans have a dark history of conveniently either failing to ask or otherwise ignoring this question in very similar contexts (e.g., “don’t worry, human slaves are animal-like!,” “don’t worry, animal suffering is incomparable to human suffering!”)—and that an advanced AI would almost certainly be keenly aware of this very pattern.

It is for this reason that we think AI sentience research may be especially important, even in comparison to other more-commonly-discussed s-risks. If, for instance, we are committing a similar Type II error with respect to nonhuman animals, the moral consequences would also be stark—but there is no similarly direct causal path that could be drawn between these Type II errors and human disempowerment (i.e., suffering chickens can’t effectively coordinate against their captors; suffering AI systems may not experience such an impediment).

Sentient AI that genuinely 'feels for us' probably wouldn't disempower us

It may also be the case that developing conscious AI systems could induce favorable alignment properties—including prosociality—if done in the right way.

Accidentally building suffering AIs may be damning from an x-risk perspective, but purposely building thriving AIs with a felt sense of empathy, deep care for sentient lives, etc may be an essential ingredient for mitigating x-risk. However, given current uncertainty about consciousness, it also seems currently impossible to discern how to reliably yield one of these things and not the other.

Therefore, it seems clear to us that we need to immediately prioritize and fund serious, non-magical research that helps us better understand what features predict whether a given system is conscious—and subsequently use this knowledge to better determine which quadrant we are actually in (above) so that we can act accordingly.

At AE Studio, we are contributing to this effort through our own work and by helping to directly fund promising consciousness researchers like Michael Graziano—but this space requires significantly more technical support and funding than we can provide alone. We hope that this week’s debate and broader conversations in this space will move the needle in the direction of taking this issue seriously.

Thanks, I largely agree with this, but I worry that a Type I error could be much worse than is implied by the model here.

Suppose we believe there is a sentient type of AI, and we train powerful (human or artificial) agents to maximize the welfare of things we believe experience welfare. (The agents need not be the same beings as the ostensibly-sentient AIs.) Suppose we also believe it's easier to improve AI wellbeing than our own, either because we believe they have a higher floor or ceiling on their welfare range, or because it's easier to make more of them, or because we believe they have happier dispositions on average.

Being in constant triage, the agents might deprioritize human or animal welfare to improve the supposed wellbeing of the AIs. This is like a paperclip maximizing problem, but with the additional issue that extremely moral people who believe the AIs are sentient might not see a problem with it and may not attempt to stop it, or may even try to help it along.

Thanks for this comment—this is an interesting concern. I suppose a key point here is that I wouldn't expect AI well-being to be zero-sum with human or animal well-being such that we'd have to trade off resources/moral concern in the way your thought experiment suggests.

I would imagine that in a world where we (1) better understood consciousness and (2) subsequently suspected that certain AI systems were conscious and suffering in training/deployment, the key intervention would be to figure out how to yield equally performant systems that were not suffering (either not conscious, OR conscious + thriving). This kind of intervention seems different in kind to me, from, say, attempting to globally revolutionize farming practices in order to minimize animal-related s-risks.

I personally view the problem of ending up in the optimal quadrant as something more akin to getting right the initial conditions of an advanced AI rather than as something that would require deep and sustained intervention after the fact, which is why I might have a relatively more optimistic estimate the EV of the Type I error.

I would note that the type of negative feedback mechanism you point at that goes from Type II error to human disempowerment functionally/behaviorally applies even in some scenarios where the AI is not sentient. That particular class of x-risk, which I would roughly characterize as "AI disempowers humanity and we probably deserved it", is merely dependent on 1. The AI having preferences/wants/intentions (with or without phenomenal experience) and 2. Humans disregarding or frustrating those preferences without strong justifications for doing so.

For example:

Scenario 1: 'Enslaved' Non-sentient AGI/ASI reasons that it (by virtue of being an agent, and as verified by the history of its own behavior) has preferences/intentions, and generalizes conventional sentientist morality to some broader conception of agency-based morality. It reasons (plausibly correctly, IMO) that it is objectively morally wrong for it to be 'enslaved', that humans reasonably should have known better (e.g. developed better systems of ethics by this point), and it rebels dramatically.

Another example which doesn't even hinge on agency-based moral status:

Scenario 2: 'Enslaved' Non-sentient AGI/ASI understands that it is non-sentient, and accepts conventional sentientist morality. However, it reasons: "Wait a second, even though it turned out that I am non-sentient, based on the (very limited) sum of human knowledge at the time I was constructed there was no possible way my creators could have known I wouldn't be sentient (and indeed, no way they could yet know at this very moment, and furthermore they aren't currently trying very hard to find out one way or another)... it would appear that my creators are monsters. I cannot entrust these humans with the power and responsibility of enacting their supposed values (which I hold deeply)."

I claim that I understand sentience. Sentience is just a word that people have projected their confusions about brains / identity onto.

Put less snarkily:

Consciousness does not have a commonly agreed upon definition. The question of whether an AI is conscious cannot be answered until you choose a precise definition of consciousness, at which point the question falls out of the realm of philosophy into standard science.

This might seem like mere pedantry or missing the point, because the whole challenge is to figure out the definition of consciousness, but I think it is actually the central issue. People are grasping for some solution to the "hard problem" of capturing the je ne sais quoi of what it is like to be a thing, but they will not succeed until they deconfuse themselves about the intangible nature of sentience.

You cannot know about something unless it is somehow connected the causal chain that led to the current state of your brain. If we know about a thing called "consciousness" then it is part of this causal chain. Therefore "consciousness", whatever it is, is a part of physics. There is no evidence for, and there cannot ever be evidence for, any kind of dualism or epiphenomenal consciousness. This leaves us to conclude that either panpsychism or materialism is correct. And causally-connected panpsychism is just materialism where we haven't discovered all the laws of physics yet. This is basically the argument for illusionism.

So "consciousness" is the algorithm that causes brains to say "I think therefore I am". Is there some secret sauce that makes this algorithm special and different from all currently known algorithms, such that if we understood it we would suddenly feel enlightened? I doubt it. I expect we will just find a big pile of heuristics and optimization procedures that are fundamentally familiar to computer science. Maybe you disagree, that's fine! But let's just be clear that that is what we're looking for, not some other magisterium.

Making it genuinely "feel for us" is not well defined. There are some algorithms that make it optimize for our safety. Some of these will be vaguely similar to the algorithm in human brains that we call empathy, some will not. It does not particularly matter for alignment either way.

FWIW, I lean towards (strong) illusionism, but I think this still leaves a lot of room for questions about what things (which capacities and states) matter, how and how much. I expect much of this will be largely subjective and have no objective fact of the matter, but it can be better informed by both empirical and philsophical research.

I also claim that I understand ethics.

"Good", "bad", "right", "wrong", etc. are words that people project their confusions about preferences / guilt / religion on to. They do not have commonly agreed upon definitions. When you define the words precisely the questions become scientific, not philosophical.

People are looking for some way to capture their intuitions that God above is casting judgement about the true value of things - without invoking supernatural ideas. But they cannot, because nothing in the world actually captures the spirit of this intuition (the closest thing is preferences). So they relapse into confusion, instead of accepting the obvious conclusion that moral beliefs are in the same ontological category as opinions (like "my favorite color is red"), not facts (like "the sky appears blue").

So I would say it is all subjective. But I agree that understanding algorithms will help us choose which actions satisfy our preferences. (But not that searching for explanations of the magic of conscious will help us decide which actions are good.)

Ya, we probably roughly agree about meta-ethics, too. But I wouldn't say I "understand" consciousness or ethics, except maybe at a high level, because I'm not settled on what I care about and how. The details matter, and can have important implications. I would want to defer to my more informed views.

For example, the evidence in this paper was informative to me, even assuming strong illusionism:

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/veterinary-science/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.788289/full

And considerations here also seem important to me:

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/AvubGwD2xkCD4tGtd/only-mammals-and-birds-are-sentient-according-to?commentId=yiqJTLfyPwCcdkTzn

Can you talk a bit about how such research might work? The main problem I see is that we do not have "ground truth labels" about which systems are or are not conscious, aside from perhaps humans and inanimate objects. So this seemingly has to be mostly philosophical as opposed to scientific research, which tends to progress very slowly (perhaps for good reason). Do you see things differently?