How the dismal science can help us end the dismal treatment of farm animals

By Martin Gould

Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

This year we’ll be sharing a few notes from my colleagues on their areas of expertise. The first is from Martin. I’ll be back next month. - Lewis

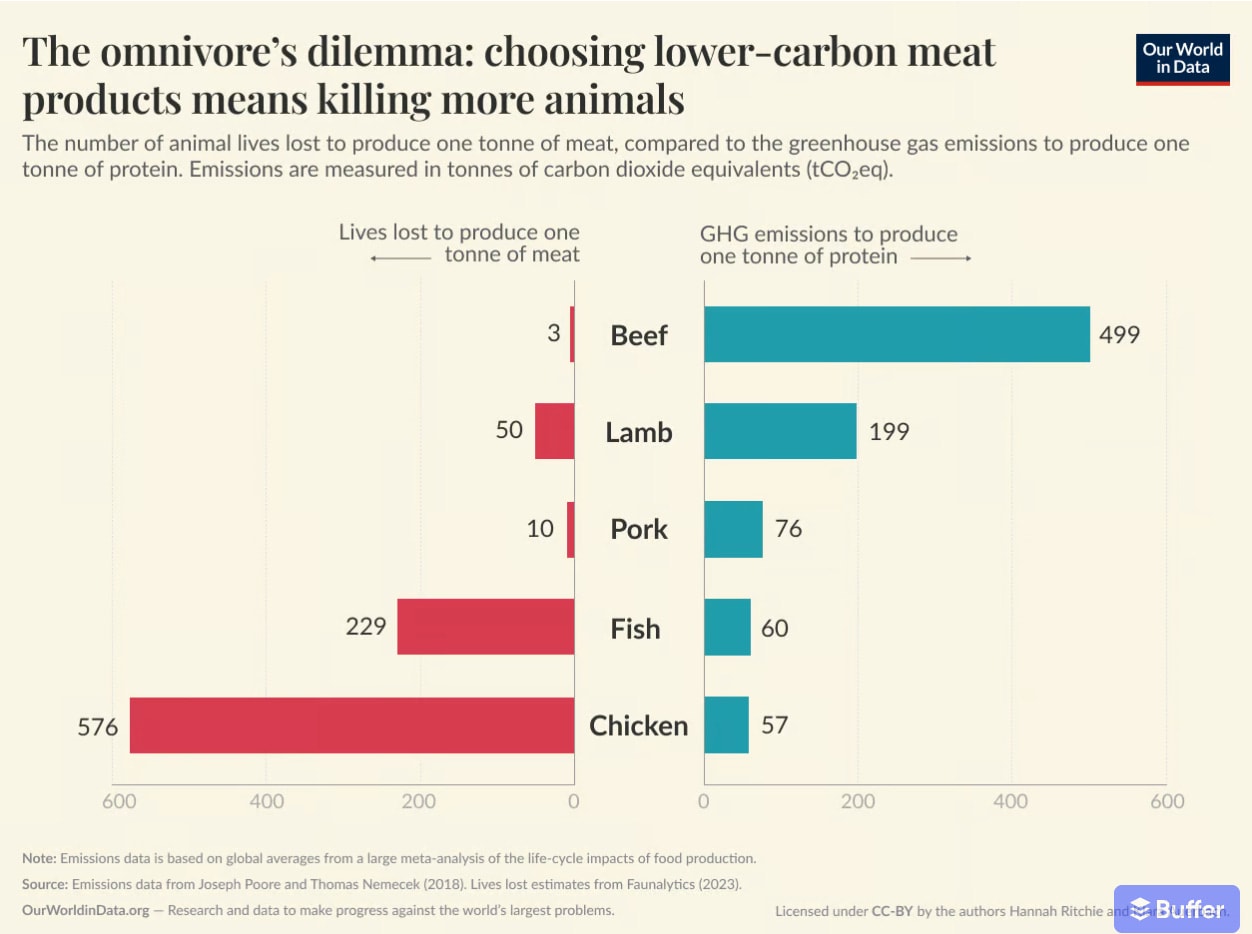

In 2024, Denmark announced plans to introduce the world’s first carbon tax on cow, sheep, and pig farming. Climate advocates celebrated, but animal advocates should be much more cautious. When Denmark’s Aarhus municipality tested a similar tax in 2022, beef purchases dropped by 40% while demand for chicken and pork increased.

Beef is the most emissions-intensive meat, so carbon taxes hit it hardest — and Denmark’s policies don’t even cover chicken or fish. When the price of beef rises, consumers mostly shift to other meats like chicken. And replacing beef with chicken means more animals suffer in worse conditions — about 190 chickens are needed to match the meat from one cow, and chickens are raised in much worse conditions.

It may be possible to design carbon taxes which avoid this outcome; a recent paper argues that a broad carbon tax would reduce all meat production (although it omits impacts on egg or dairy production). But with cows ten times more emissions-intensive than chicken per kilogram of meat, other governments may follow Denmark’s lead — focusing taxes on the highest emitters while ignoring the welfare implications.

This case underscores a key lesson for animal advocacy: policies that seem like progress can backfire if they don’t account for how consumers and industry actually respond. Farm animal economics can reveal these unintended consequences, equipping advocates to design strategies that achieve their goals without creating new harms. Here are five more insights from economics for animal advocates.

1. Blocking local factory farms can mean animals are farmed in worse conditions elsewhere

Halting plans for a large, polluting factory farm feels like a clear win — no ammonia-laden air burning residents’ lungs, no waste runoff contaminating local drinking water, and seemingly fewer animals suffering in industrial confinement. But that last assumption deserves scrutiny. What protects one community might actually condemn more animals to worse conditions elsewhere.

Consider the UK: Local groups celebrate blocking new chicken farms. But because UK chicken demand keeps growing — it rose 24% from 2012-2022 — the result of fewer new UK chicken farms is just that the UK imports more chicken: it almost doubled its chicken imports over the same time period. While most chicken imported into the UK comes from the EU, where conditions for chickens are similar, a growing share comes from Brazil and Thailand, where regulations are nonexistent. Blocking local farms may slightly reduce demand via higher prices, but it also risks sentencing animals to worse conditions abroad.

The same problem haunts government welfare reforms — stronger standards in one country can just shift production to places with worse standards. But advocates are getting smarter about this. They're pushing for laws that tackle both production and imports at once. US states like California have done this — when it banned battery cages, it also banned selling eggs from hens caged anywhere. The EU is considering the same approach. It's a crucial shift: without these import restrictions, both farm bans and welfare reforms risk exporting animal suffering to places with even worse conditions. And advocates have prioritized corporate policies, which avoid this problem, as companies pledge to stop selling products associated with the worst animal suffering (like caged eggs), regardless of where they are produced.

2. Mergers among meat companies can reduce animal farming

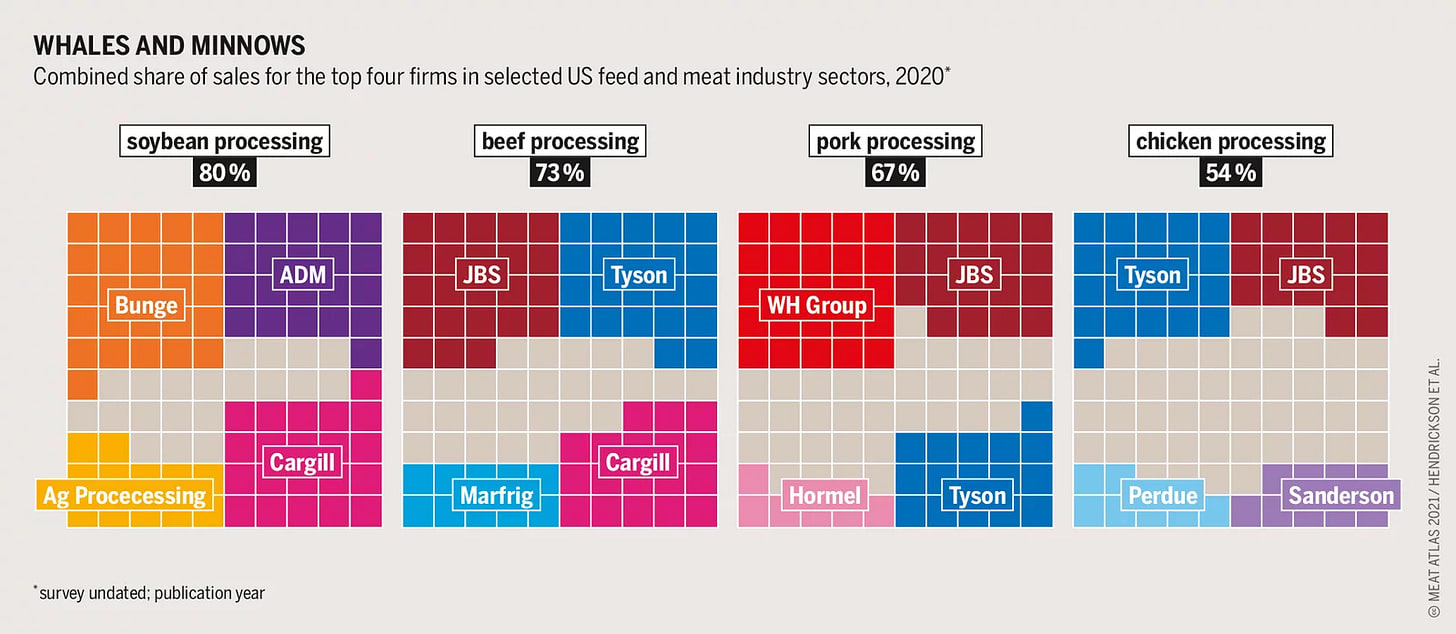

Animal advocates often decry the market concentration in agribusiness. They have a point: most US chicken, pork, and beef processing is done by just four giant companies in each sector. But high market concentration is actually a mixed bag for animals.

Take the 2022 merger between the third- and seventh-largest US chicken producers. With more market power, the merged company, Wayne-Sanderson Farms, increased profits by raising prices while cutting supply, leading to fewer birds being raised and killed. It seems to have reduced total US chicken production by 0.26%-0.57%. That’s 24–52 million fewer chickens slaughtered annually. Given the steady rise in US chicken production, with little else shifting the trend, this is notable.

That said, smaller companies have benefits for animals. When an industry is fragmented, it will struggle to coordinate lobbying efforts against legislative welfare reforms. And consolidation may also make corporate welfare reforms harder to secure — in the US, change has been slower in the heavily concentrated chicken industry than in the more fragmented egg sector.

But breaking up the industry won’t bring back the small farms of children’s picture books. Fewer really large producers would likely just create more mid-sized, fiercely competitive companies operating with similar factory farming methods. Factory farming presents a unique case where consolidation might inadvertently serve animal welfare by reducing total production — a clear benefit that needs to be weighed against consolidation’s costs.

3. There may be more economic policy tools available to help animals

Advocates may feel constrained by economics, as the field has a reputation for prioritizing efficiency and consumer interests over ethics. But economics doesn’t have to defend the status quo, with enough ingenuity, it can point to new solutions.

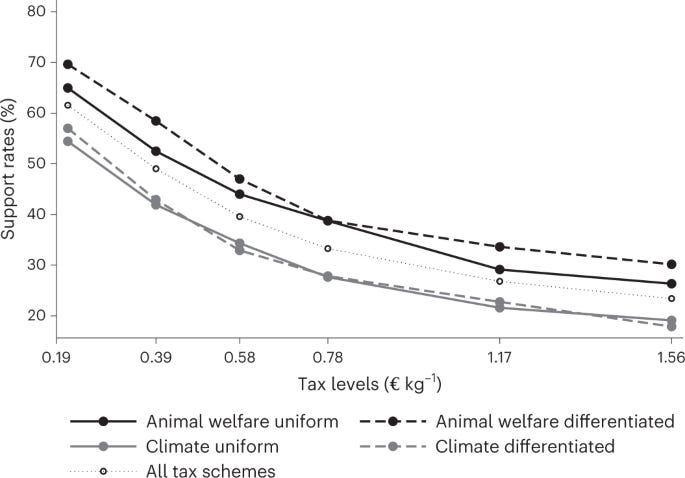

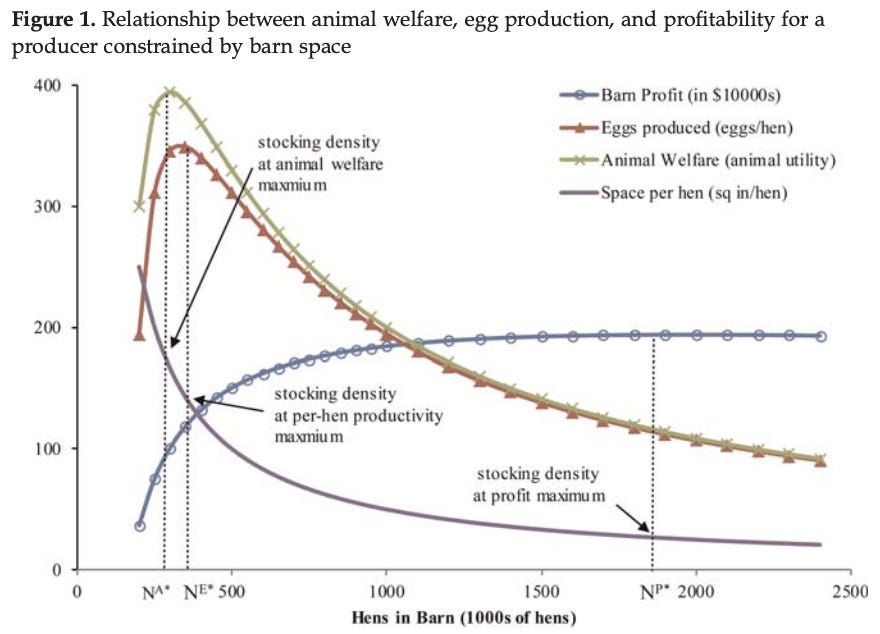

Libertarian economist Tyler Cowen proposes taxing producers when they use low-welfare approaches (like factory farms) and subsidizing them when they use higher-welfare methods (such as pasture-based systems). The goal is to improve animal welfare by aligning economic incentives with ethical standards. An expert commission in Germany in 2020 proposed a similar policy, and while it hasn't been taken up, a survey showed over 50% of Germans supported a version of this scheme.

Some want to take this further by creating a whole new market for animal welfare, as was set-up for climate emissions reduction. Agricultural economist Jayson Lusk suggests developing a new, tradable commodity ('Animal Well-being Units') which farmers can generate by treating animals well and sell to companies who need them. While it sounds complicated, a simpler version is already in practice in Asia, where companies can buy cage-free egg credits to meet their commitments in places where cage-free farming is just getting started.

4. Curbing wild-caught fishing may not reduce fish suffering

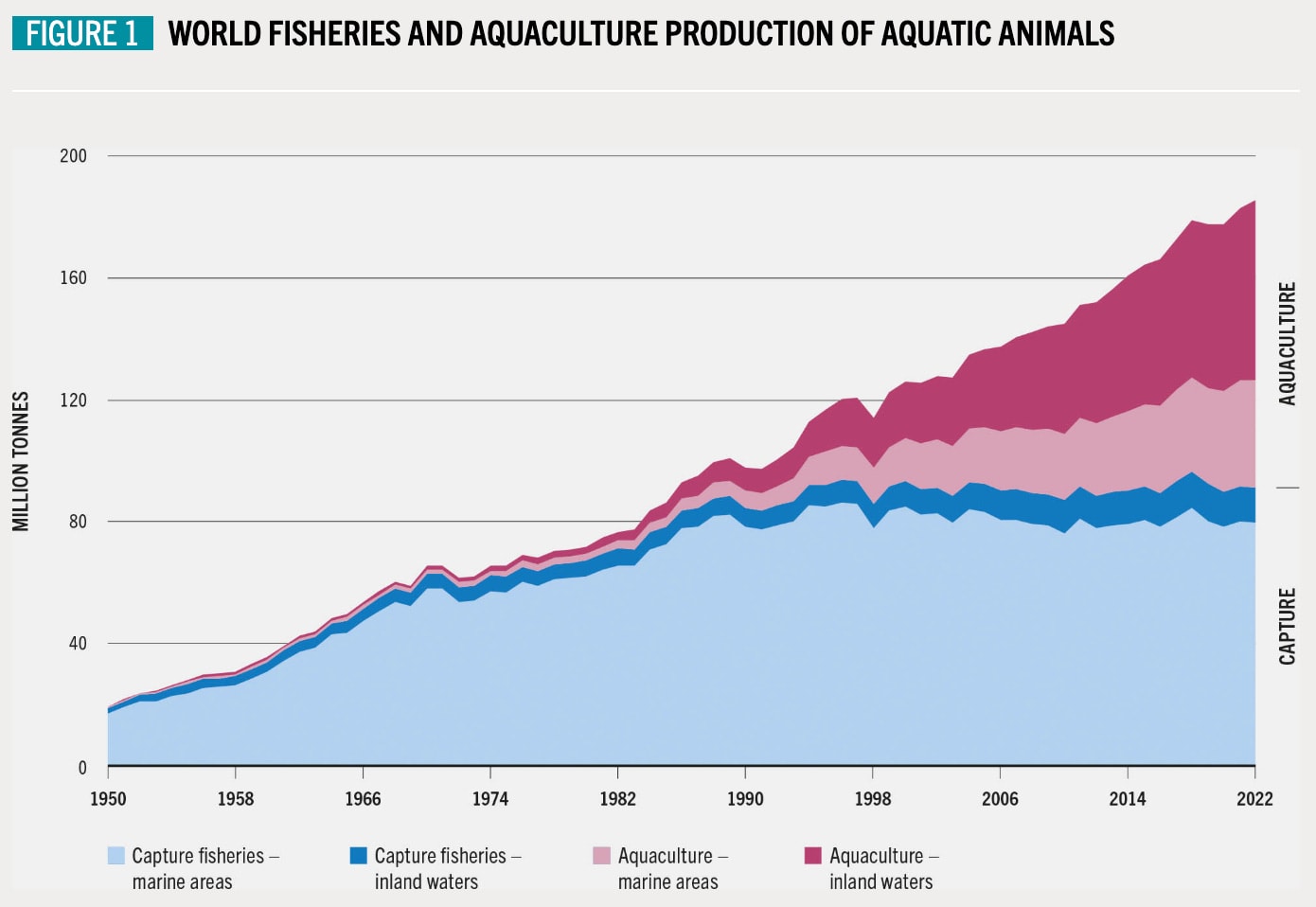

Pulling fish from the ocean is a grisly business — they’re yanked from their natural habitat, left to suffocate for minutes if not hours, and often eviscerated alive. Curtailing this industry seems clearly good. But the actual effects of doing so are far more ambiguous.

When fishing reaches its natural limits or is capped to save the oceans, production often shifts to factory farms. Since the 1990s, wild caught fishing hauls have stagnated while aquaculture production has more than tripled. The lack of wild caught fish has done little to dent demand from fish consumers – global per person consumption has risen 50% and total consumption 130%.

And in the long run, wild fishing restrictions can facilitate a fish population bounceback, which could increase wild fishing hauls. When fishing pauses, populations recover, sometimes so well that more fish can be caught sustainably than before the restrictions. For example, when Norway and Russia reduced the quota on cod in the Barents Sea in the 1990s, populations bounced back and in the 2010s, 2-3 times more fish were being pulled from the sea than prior to the quota reduction. International institutions like the OECD are wise to this and recommend fishing restrictions so fishers can maximize future fishing hauls.

How these factors net out is unclear. World Bank projections, which rely on simplified assumptions, suggest that if wild fishing continues to stagnate, aquaculture will expand to fill the gap. Ultimately the real-world trade-offs remain murky. For now, advocates pushing to curb wild fishing can’t be sure they’re reducing the total number of fish suffering – and they may just be driving more fish into factory farms instead.

5. Advocates should reclaim economics to make the case for animals

Agribusiness lobbying groups often co-opt economic analysis to argue against any animal welfare improvements. But focusing solely on financial costs to industry is a misuse of economics, which provides the tools to tally up both costs and benefits — including benefits to animals. It’s time for animal advocates to reclaim economics and put it to use in our legislative battles.

The stalling of the EU farm animal welfare reforms in 2024 illustrates the damage misused economics can do. When the Commission evaluated a set of proposed animal welfare changes, they applied a fundamental imbalance: they meticulously calculated industry costs, while not bothering to count benefits to animals.

In recent years, economists have started adapting human health metrics to quantify animal suffering across different farming systems and creating measurement frameworks that actually count animal experiences. Their work on "animal quality-adjusted life years" offers a practical way to include animal welfare in standard economic calculations.

These frameworks require further development and academic acceptance. And until we properly account for animal suffering in economic terms, even scientifically rigorous reforms will struggle against the agriculture industry’s numbers game.

Closing the ledger: utility for all

John Stuart Mill, one of the founders of modern economics, was also one of the first modern animal advocates. In 1848, he argued that the government had a duty to protect animals from cruelty, and that England’s animal protection laws at the time were too weak. He even proposed comparing a practice’s benefits to humans with its harms to animals, effectively pioneering animal welfare cost-benefit analysis.

This insight was largely forgotten for 170 years. Economics was instead used to justify all manner of “economically beneficial” animal mistreatment. It’s time for advocates to reclaim economics as a tool to weigh not just human interests, but the interests of animals as well — returning to Mill's original, more humane vision.

Cross-posting my comment from Substack:

How sure are we that this is the case? Matt Yglesias argues:

Maybe the political economy around mid-size factory farms is different from that around car dealerships, such that these dynamics don't apply or apply differently. But I would want to better understand the differences. (Is it just that factory farms don't sell directly to consumers? But my hometown had a membrane filter manufacturing plant when I was growing up, and I think it was similarly locally influential.)

[cross-posting my response from Substack :)]

Interesting point. In theory, when an industry has many companies there’s an incentive to free ride on the lobbying efforts of others and overall there’s less lobbying. Whereas if an industry has only one company it captures all the benefits of lobbying, so does more of it.

I don’t know much about US auto dealers, but this paper seems to find that even within that industry, consolidation leads to increased lobbying (if it's within the same state). But what your example may point to is that industry concentration i... (read more)