This would have been a submission to the FTX AI worldview prize. I’d like to thank Daniel Kokotajlo, Ege Erdil, Tamay Besiroglu, Jaime Sevilla, Anson Ho, Keith Wynroe, Pablo Villalobos and Simon Grimm for feedback and discussions. Criticism and feedback are welcome. This post represents my personal views.

Update Dec 2023: I now think timelines faster than my aggressive prediction in this post are accurate. My median is now 2030 or earlier.

The causal story for this post was: I first collected my disagreements with the bio anchors report and adapted the model. This then led to shorter timelines. I did NOT only collect disagreements that lead to shorter timelines. If my disagreements would have led to longer timelines, this post would argue for longer timelines.

I think the bio anchors report (the one from 2020, not Ajeya’s personal updates) puts too little weight on short timelines. I also think that there are a lot of plausible arguments for short timelines that are not well-documented or at least not part of a public model. The bio anchors approach is obviously only one possible way to think about timelines but it is currently the canonical model that many people refer to. I, therefore, think of the following post as “if bio anchors influence your timelines, then you should really consider these arguments and, as a consequence, put more weight on short timelines if you agree with them”. I think there are important considerations that are hard to model with bio anchors and therefore also added my personal timelines in the table below for reference.

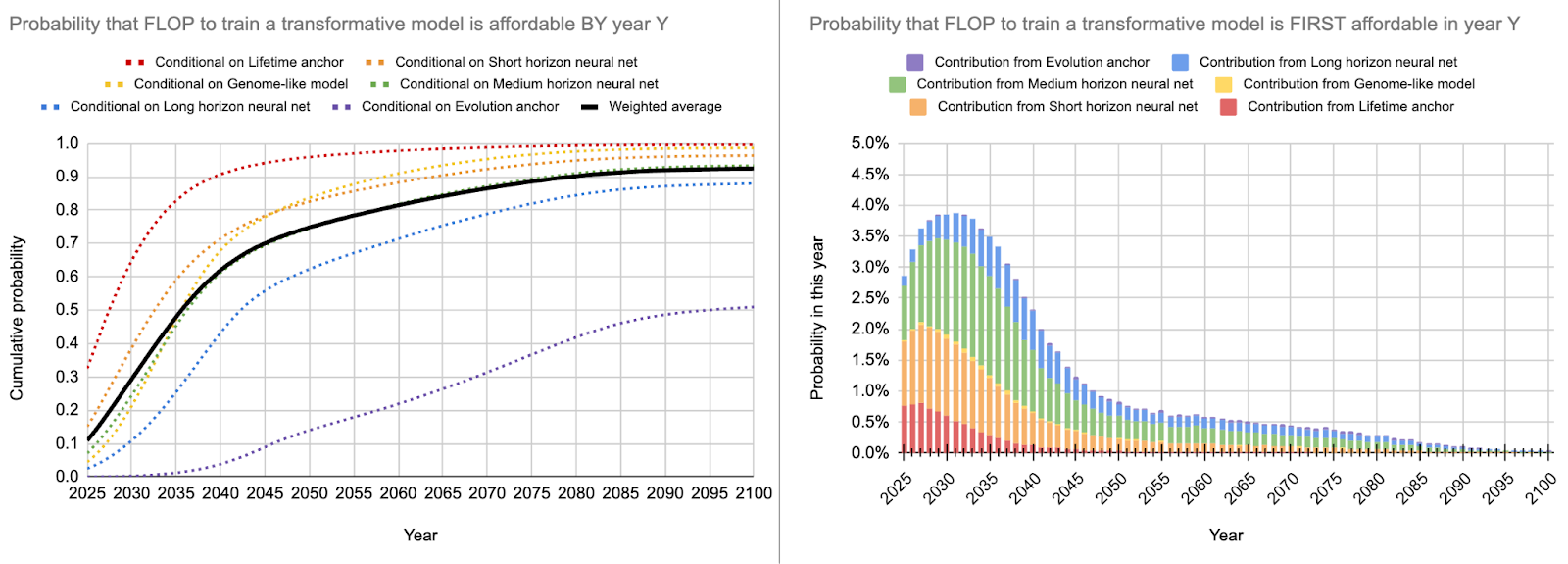

My best guess bio anchors adaption suggests a median estimate for the availability of compute to train TAI of 2036 (10th percentile: 2025, 75th percentile: 2052). Note that this is not the same as predicting the widespread deployment of AI. Furthermore, I think that the time “when AI has the potential to be dangerous” is earlier than my estimate of TAI because I think that this poses a lower requirement than the potential to be economically transformative (so even though the median estimate for TAI is 2036, I wouldn’t be that surprised if, let’s say 2033 AIs, could deal some severe societal harm, e.g. > $100B in economic damage).

You can find all material related to this piece including the colab notebook, the spreadsheets and the long version in this google folder.

Executive summary

I think some of the assumptions in the bio anchors report are not accurate. These disagreements still apply to Ajeya’s personal updates on timelines. In this post, I want to lay out my disagreements and provide a modified alternative model that includes my best guesses.

Important: To model the probability of transformative AI in a given year, the bio anchors report uses the availability of compute (e.g. see this summary). This means that the bio anchors approach is NOT a prediction for when this AI has been trained and rolled out or when the economy has been transformed by such an ML model, it merely predicts when such a model could be trained. I think it could take multiple (I guess 0-4) years until such a model is engineered, trained and actually has a transformative economic impact.

My disagreements

You can find the long version of all of the disagreements in this google doc, the following is just a summary.

- I think the baseline for human anchors is too high since humans were “trained” in very inefficient ways compared to NNs. For example, I expect humans to need less compute and smaller brains if we were able to learn on more data or use parallelization. Besides compute efficiency, there are further constraints on humans such as energy use, that don’t apply to ML systems. To compensate for the data constraint, I expect human brains to be bigger than they would need to be without them. The energy constraint could imply that human brains are already very efficient but there are alternative interpretations. [jump to section]

- I think the report does not include a crucial component of algorithmic efficiency which I call “software for hardware” for lack of a better description. It includes progress in AI accelerators such as TPUs (+the software they enable), software like PyTorch, compilers, libraries like DeepSpeed and related concepts. The current estimate for algorithmic efficiency does not include the progress coming from this billion-dollar industry. [jump to section]

- I think the report’s estimate for algorithmic progress is too low in general. It seems like progress in transformers is faster than in vision models and the current way of estimating algorithmic progress doesn’t capture some important components. [jump to section]

- I think the report does not include algorithmic improvements coming from more and more powerful AI, e.g. AI being used to improve the speed of matrix multiplication, AI being used to automate prompt engineering or narrow AIs that assist with research. This automation loop seems like a crucial component for AI timelines. [jump to section]

- I think the evolution anchor is a bit implausible and currently has too much weight. This is mostly because SGD is much more efficient than evolutionary algorithms and because ML systems can include lots of human knowledge and thus “skip” large parts of evolution. [jump to section]

- I think the genome anchor is implausible and currently has too much weight. This is mostly because the translation from bytes in the genome to parameters in a NN seems implausible to me. [jump to section]

- I think the report is too generous with its predictions about hardware progress and the GPU price-performance progress will get worse in the future. This is my only disagreement that makes timelines longer. Update Dec 2023: I was probably wrong here. Compute progress is faster when you control for precision and tensor cores [jump to section]

- Intuitions: Things in AI are moving faster than I anticipated and people who work full-time with AI often tend to have shorter timelines. Both of these make me less skeptical of short or very short timelines. [jump to section]

- I think the report’s update against current levels of compute is too radical. A model like GPT-5 or Gato 3 could be transformative IMO (this is not my median estimate but it doesn’t seem completely implausible). I provide reasons for why I think that these “low” levels of compute could already be transformative. [jump to section]

- There are still a number of things I’m not modeling or am unsure about. These include regulation and government interventions, horizon length (I’m not sure if the concept captures exactly what we care about but don’t have a better alternative), international conflicts, pandemics, financial crises, etc. All of these would shift my estimates back by a bit. However, I think AI is already so powerful that these disruptions can’t stop its progress--in a sense, the genie is out of the bottle. [jump to section]

The resulting model

The main changes from the original bio anchors model are

- Lowering the FLOP/s needed for TAI compared to Human FLOP/s

- Lowering the doubling time of algorithmic progress

- Changing the weighing of some anchors

- Some smaller changes; see here for details.

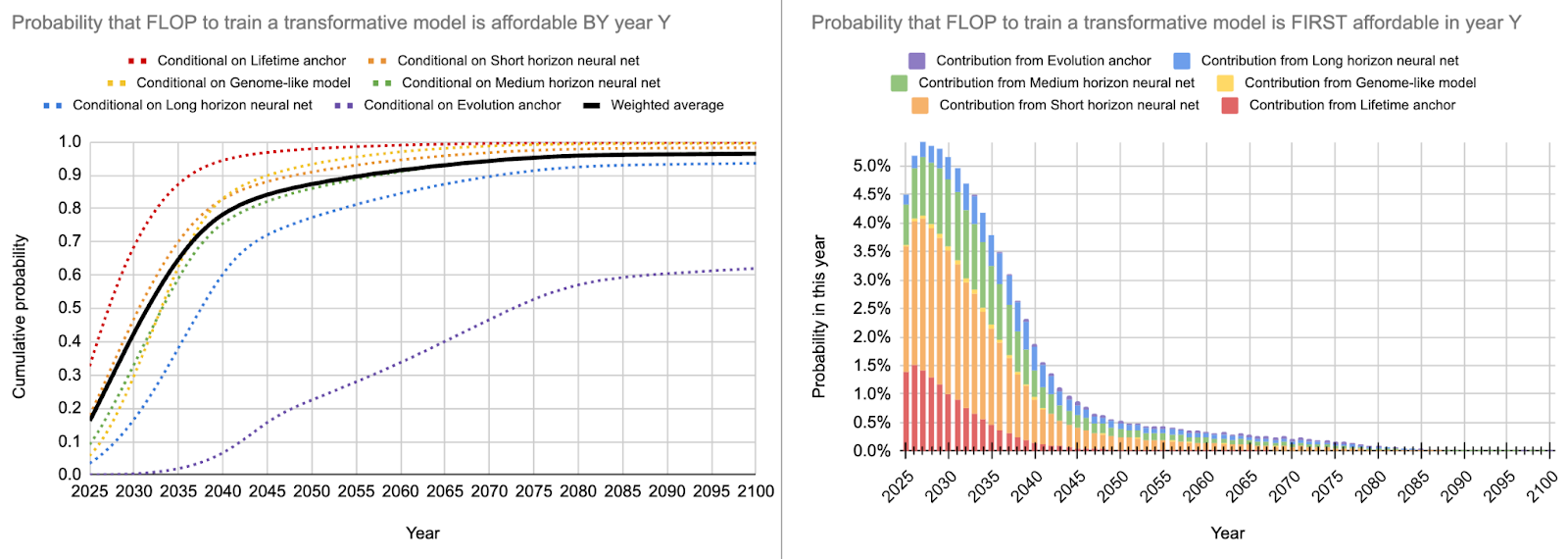

I tried to change as few parameters as possible from the original report. You can find an overview of the different parameters in the table below and the resulting best guess in the following figure.

| Aggressive - bio anchors (Marius) | Best guess - bio anchors (Marius) | Independent impression (Marius) | Ajeya’s best guess (2020) | |

| Algorithmic progress doubling time | 1.-1.3 years | 1.3-1.6 years | 1.3-1.6 years | 2-3.5 years |

Compute progress doubling time | 2.5 years | 2.8 years | 3 years | 2.5 years |

| Model FLOPS vs. brain FLOPS (=1e15) median | -1 | -0.5 | -0.2 | +1 |

| Lifetime anchor | 16% | 10% | 10% | 5% |

| Short NN anchor | 40% | 24% | 30% | 20% |

| Medium NN anchor | 20% | 35% | 31% | 30% |

| Long NN anchor | 10% | 17% | 13% | 15% |

| Evolution anchor | 3% | 3% | 5% | 10% |

| Genome anchor | 1% | 1% | 1% | 10% |

| 10th percentile estimate | <2025 | ~2025 | ~2028 | ~2032 |

| Median(=50%) estimate | ~2032 | ~2036 | ~2041 | ~2052 |

| 75th percentile estimate | ~2038 | ~2052 | ~2058 | ~2085 |

My main takeaways from the updates to the model are

- If you think that the compute requirements for AI is lower than that for humans (which I think is plausible for all of the reasons outlined below) then most of the probability mass for TAI is between 2025 and 2035 rather than 2035 and 2045 as Ajeya’s model would suggest.

- In the short timeline scenario, there is some probability mass before 2025 (~15%). I would think of this as the “transformer TAI hypothesis”, i.e. that just scaling transformers for one more OOM and some engineering will be sufficient for TAI. Note that this doesn’t mean there will be TAI in 2025 just that it would be possible to train it.

- Thinking about the adaptions to the inputs of the bio anchor model and then computing the resulting outputs made my timelines shorter. I didn’t actively intend to produce shorter timelines but the more I looked at the assumptions in bio anchors, the more I thought “This estimate is too conservative for the evidence that I’m aware of”.

- The uncertainty from the model is probably too low, i.e. the model is overconfident because core variables like compute price halving time and algorithmic efficiency are modeled as static singular values rather than distributions that change over time. This is one reason why my personal timelines (as shown in the table) are a bit more spread than my best guess bio anchors adaption.

To complete the picture, this is the full distribution for my aggressive estimate:

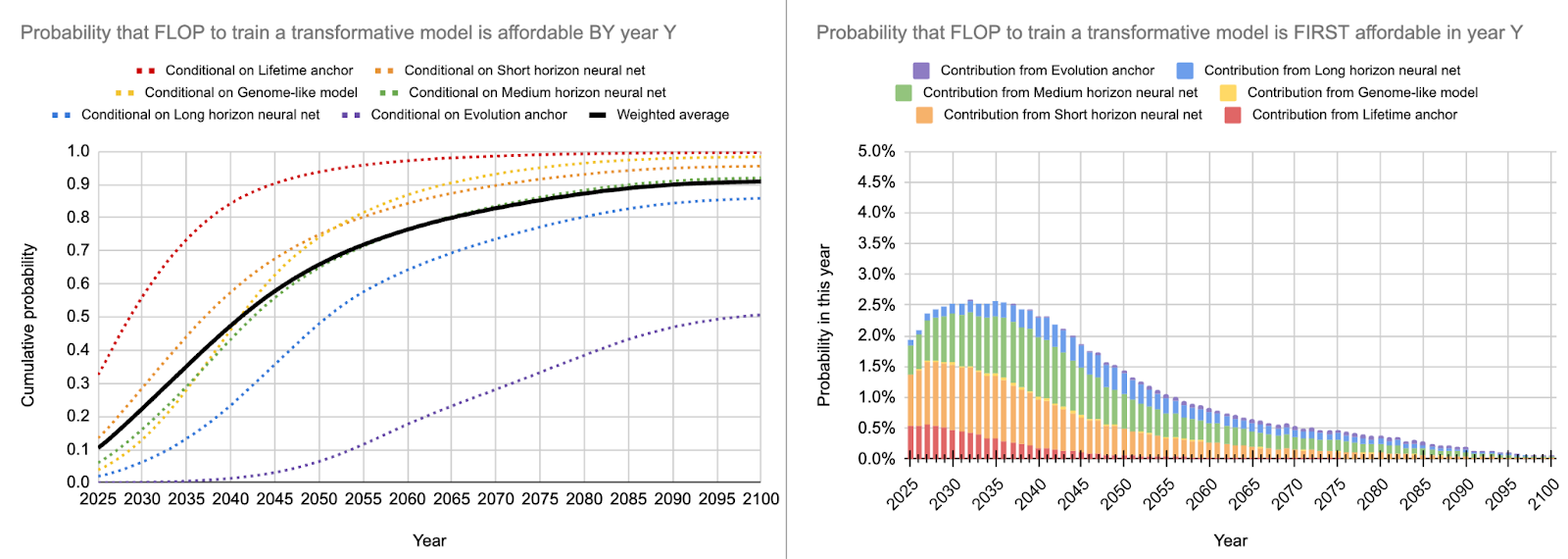

And for my independent impression:

Note that the exact weights for my personal estimate are not that meaningful because I adapted them to include considerations that are not part of the current bio anchors model. Since it is hard to model something that is not part of the model, you should mostly ignore the anchor weights and only look at the final distribution. These “other considerations” include unknown unknowns, disruptions of the global economy, pandemics, wars, etc. all of which add uncertainty and lengthen timelines.

As you can see, I personally still think that 2025-2040 is the timespan that is most likely for TAI but I have more weight on longer timelines than the other two estimates. My personal timelines (called independent impression in the table) are also much more uncertain than the other estimates because I find arguments for very short and for much longer timelines convincing and don’t feel like I have a good angle for resolving this conflict at the moment. Additionally, compute halving time and algorithmic progress halving time are currently static point estimates and I think optimally they would be distributions that change over time. This uncertainty is currently not captured and I, therefore, try to introduce it post-hoc. Furthermore, I want to emphasize that I think that relevant dangers from AI arise before we get to TAI, so don’t mistake my economic estimates for an estimate of “when could AI be dangerous”. I think this can happen 5-15 years before TAI, so somewhere between 2015 and 2035 in my forecasts.

Update: After more conversations and thinking, my timelines are best reflected by the aggressive estimate above. 2030 or earlier is now my median estimate for AGI and I'm mostly confused about TAI because I have conflicting beliefs about how exactly the economic impact of powerful AI is going to play out.

Final words

There is a chance I misunderstood something in the report or that I modified Ajeya’s code in an incorrect way. Overall, I’m still not sure how much weight we should put on the bio anchors approach to forecasting TAI in general, but it currently is the canonical approach for timeline modeling so its accuracy matters. Feedback and criticism are appreciated. Feel free to reach out to me if you disagree with something in this piece.

In general, I have noticed a pattern where people are dismissive of recursive self improvement. To the extent people are still believing this, I would like to suggest this is a cached thought that needs to be refreshed.

When it seemed like models with a chance of understanding code or mathematics were a long ways off - which it did (checks notes) two years ago, this may have seemed sane. I don't think it seems sane anymore.

What would it look like to be on the precipice of a criticality threshold? I think it looks like increasingly capable models making large strides in coding and mathematics. I think it looks like feeding all of human scientific output into large language models. I think it looks a world where a bunch of corporations are throwing hundreds of millions of dollars into coding models and are now in the process of doing the obvious things that are obvious to everyone.

There's a garbage article going around with rumors of GPT-4, which appears to be mostly wrong. But from slightly-more reliable rumors, I've heard it's amazing and they're picking the low-hanging data set optimization fruits.

The threshold for criticality, in my opinion, requires a model capable of understanding the code that produced it as well as a certain amount of scientific intuition and common sense. This no longer seems very far away to me.

But then, I'm no ML expert.