About a year ago, after working with the Effective Thesis Project, I started my undergraduate thesis on value drift in the effective altruism movement. I interviewed eighteen EAs about their experiences with value drift and used a grounded theory approach to identify common themes. This post is a condensed report of my results. The full, official version of the thesis can be found here.

Note that I’ve changed some of the terms used in my thesis in response to feedback, specifically “moral drift”, “internal value drift”, and “external value drift”. This post uses the most up-to-date terminology at time of posting, though these terms still a work-in-progress.

Summary

- Value drift is a term EAs and rationalists use to refer to changes in our values over time, especially changes away from EA and other altruistic values.

- We want to promote morally good value changes and avoid morally bad value changes, but distinguishing between the two can be difficult since we tend to be poor judges of our own morality.

- EAs seem to think that value drift is most likely to affect the human population as a whole, less likely to affect the EA community, and even less likely to affect themselves. This discrepancy might be due to an overconfidence bias, so perhaps EAs ought to assume that we’re more likely to value drift than we intuitively think we are.

- Being connected with the EA community, getting involved in EA causes, being open to new ideas, prioritizing a sustainable lifestyle, and certain personality traits seem associated with less value drift from EA values.

- The study of EAs’ experiences with value drift is rather neglected, so further research is likely to be highly impactful and beneficial for the community.

Background

What is Value Drift?

As far as I can tell, “value drift” is an expression that was first used by the rationalist community, in reference to AI safety. It has not been discussed nor studied outside of the rationalist and EA communities - at least, not using the term “value drift.”

Value drift has been defined as broadly as changes in values and as narrowly as losing motivation to do altruistic things. People seem to see the former as the technical definition and the latter as what the term implies, as value drift away from EA values is often seen as the most concerning value drift to an EA who wants to remain an EA, or altruistic more generally. However, we can certainly experience value drift towards EA values or experience value drift that keeps us just as aligned with EA.

NB: Throughout this post, I use value drift to refer to a shift away from EA values, unless I specify otherwise.

I discuss a few different types of value drift throughout this post:

- Hierarchical value drift: a change in one’s hierarchy of values in which a value is not lost or gained, but rather its priority is changed.

- Transformative value drift: losing a previously-held value or gaining a new value.

- Abstract value drift: changes in abstract values, such as happiness or non-suffering.

- Concrete value drift: changes in concrete vales, such as effective altruism, animal welfare, global health, or existential risk-prevention.

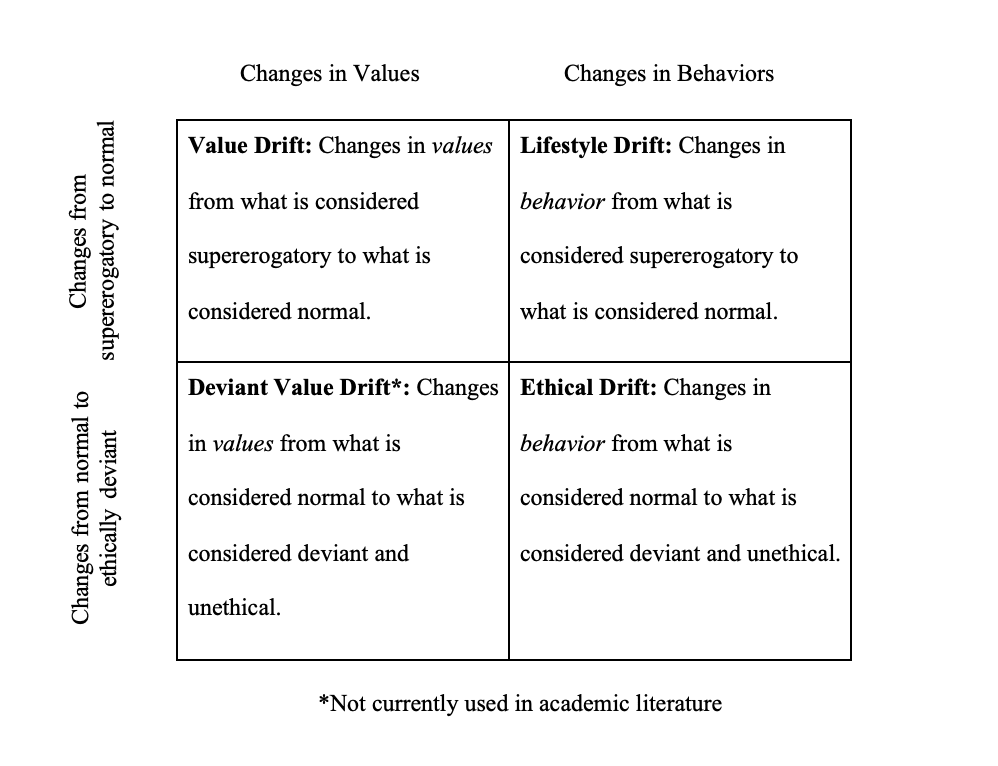

Value drift can lead us to act less morally than we otherwise would. However, it’s possible that our behaviors can change without our values changing. Darius Meissner’s forum post, “Concrete Ways to Reduce Value Drift and Lifestyle Drift”, makes the important distinction between value drift and lifestyle drift, where value drift refers to changes in values and lifestyle drift refers to changes in behaviors, often as a result of circumstances. Some academic research highlights a similar phenomenon called ethical drift, which refers specifically to behavior changes from conforming behavior to deviant, unethical behavior. One example of ethical drift is fraud in businesses; an employee might resort to fraud to cover up a bad quarter or two, then go down the “slippery slope” where committing fraud becomes the norm. I also propose the use of the term deviant value drift to refer to a similar phenomenon, but a movement from conforming values to deviant, unethical values.

I map the relationship between these four types of “drift” using the following chart:

Some of these terms have received criticism for not being intuitive, accurate, or precise enough, so further fine-tuning of this terminology would be useful.

Values are generally defined as what individuals perceive to be important in life. By that definition, people must think their values are good. So, changes in the morality of our values are likely more difficult to identify than changes in our behaviors, since we think our values are good regardless of how moral or immoral they actually are.

Changes from conforming values to deviant values might also be less likely to be noticed than changes from supererogatory values (i.e. values that go above society’s expectations of decency) to conforming values because self-serving biases make it easier to see when we are (or were previously being) moral than when we are being immoral.

Hence, deviant value drift might be the most difficult to notice in ourselves, while lifestyle drift is the easiest to notice in ourselves, though it’s still likely to go unnoticed.

For those wanting to further background literature on value drift, I recommend:

- Joey Savoie’s forum post "Empirical Data on Value Drift"

- Daniel Gambacorta’s podcast “Value Drift and How Not to Be Evil” Part I & Part II on Global Optimum

- From Rethink Priorities’ EA Survey 2018 Series, How Long Do EAs Stay in EA? and Do EA Survey Takers Keep Their GWWC Pledge?

Why Care About Value Drift?

Value drift can impair one’s long-term impact. If someone loses their altruistic values over the course of their life, their impact might be lower than it otherwise would have if they had kept those values, if those values affect their motivation to pursue altruistic behaviors such as donating to charity, partaking in EA projects, or pursuing high-impact careers.

Identifying effective ways to prevent value drift, then, might be beneficial for one’s social impact. However, it also incurs the risk of preventing morally positive value changes. Hence, understanding the nature of value drift, including how likely it is to have morally positive effects or morally negative effects, is important to informing how EAs should respond to the possibility of value drift.

Further, If particular traits or circumstances make someone more or less prone to value drift, then people holding those traits or in those circumstances might want to take this into account in considering their plans for impact. But even if one’s individual likelihood of experiencing value drift is impossible to predict, knowing how likely the average EA is to experience value drift can inform one’s plans for impact.

Decisions that are affected by how likely one is to experience value drift include:

- Short-term vs. Long-term optimization: If someone is prone to value drift, perhaps they should have an impact as quickly as possible, as they may not be motivated to do so in a few years. If someone is not prone to value drift, perhaps they should take more time to develop career capital so that they can have a larger impact later on.

- Flexibility vs. Lock-in: If someone is prone to value drift, putting money into a Donor Advised Fund or setting up recurring donations through your favorite charity or an app like Momentum might be useful for maintaining giving commitments, and developing specialized career capital may be useful for maintaining career-level impact. If someone is not prone to value drift, investing to donate later or saving up to get your donation matched by giving via Facebook on Giving Tuesday may make their giving more impactful, and developing flexible career capital may be useful for allowing one to pursue whatever career path is most impactful.

- Career Decisions: If certain careers lead to more value drift, EAs should factor this into their career choices, and perhaps EA organizations should consider this in deciding which careers they promote. We might hypothesize that people in careers where incentives are not entirely aligned with one’s morals (e.g. academia, politics, earning-to-give) may be more prone to value drift. If these hypotheses are supported, we might deprioritize these career paths, or try to find ways to mitigate the risk of value drift for people in these career paths.

Lastly, the existence of value drift affects the life and growth of the EA community. If rates of value drift are higher than the rates at which EA gains new members, then the EA community will die out. A declining EA community might also raise suspicions in current and potential EAs, which could accelerate the rates of decline.

Are Value Changes Worth Avoiding?

Changes in values can be morally good, morally bad, or morally neutral. In a perfect world, people would simply embrace morally good value changes and avoid morally bad value changes. However, most people probably have a hard time noticing if their values are morally bad, or worse than they could be, because, by definition, values are important to us. If someone believes something is completely morally wrong, they likely will not value it highly, if at all. Even the most immoral people likely think their actions are contributing to a greater good.

Can we tell if our values changes are morally good or morally bad? Perhaps logic and reason might help us compare the morality of certain sets of values, but we are still subject to a lot of self-serving biases that make it difficult for them to evaluate the morality of their values objectively.

If one assumes that we have absolutely no way of knowing whether the values we hold are morally good or morally bad, it might be worth looking at how likely it is that our values are morally good or morally bad. If our values are likely to be morally good, then we probably, generally, want to avoid value changes. If our values are likely to be morally bad, we probably, generally, don’t want to avoid value changes.

Moral uncertainty exists, and we cannot know for sure if the values most EAs hold are morally the best values we can hold, or even morally good values to hold in general. In general, more exploration on the moral dimensions of avoiding or embracing value changes might be useful.

Throughout this research, I assume that keeping people aligned with EA values is preferable to most other outcomes. However, I am highly uncertain about this, and I think others should be as well.

Research & Findings

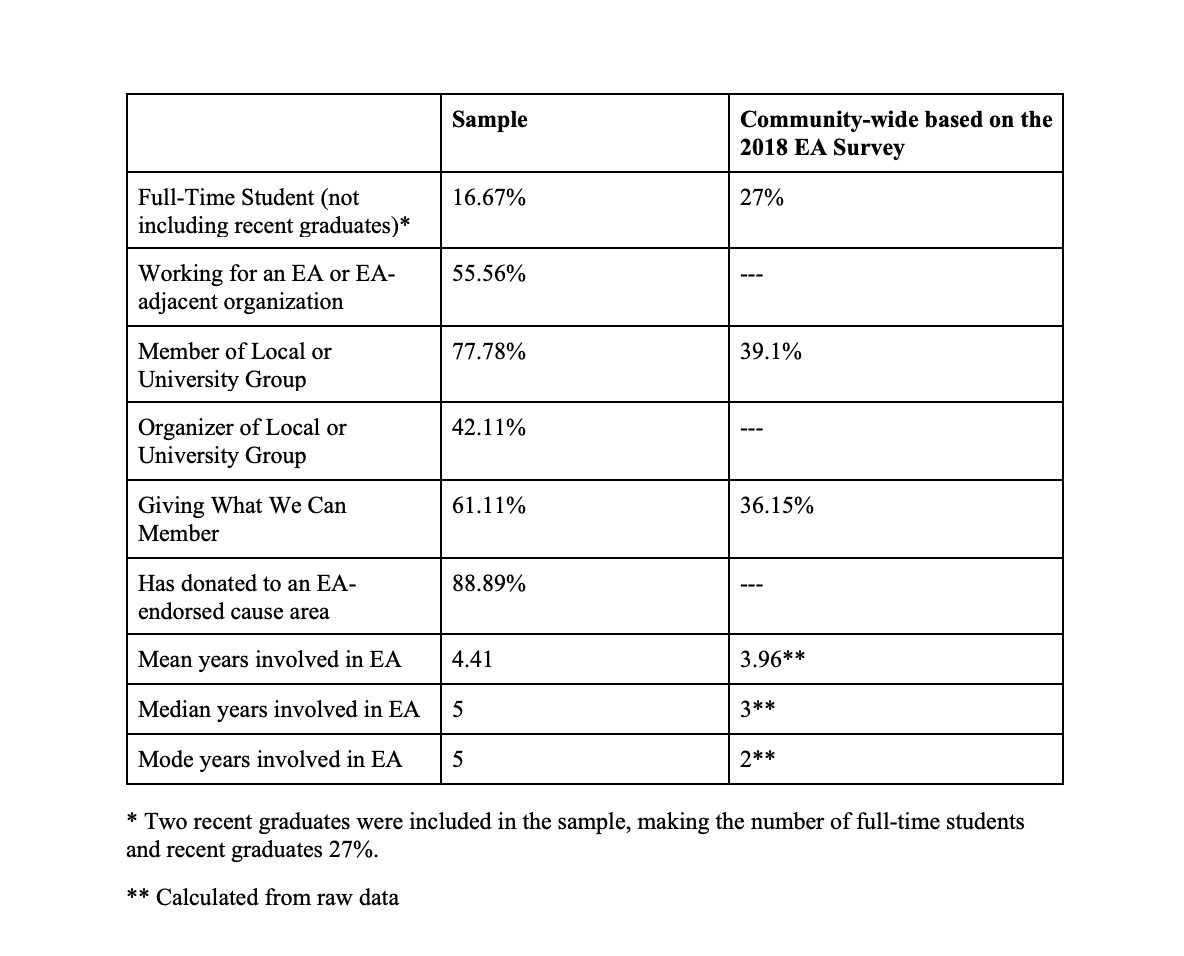

I interviewed eighteen EAs using qualification criteria similar to Joey Savoie’s study: participants had to have been involved in EA for at least 6 months and to have taken at least one EA action (e.g. getting involved in a local group, taking the Giving What We Can pledge, working on an EA project). I then used a grounded theory approach to identify common themes in the interviews.

Below is a table comparing how involved participants in this study were compared to the rates of involvement in the EA community as a whole.

As expected, this sample appears to be subject to a significant survivorship bias; the participants of the study seemed to be substantially more involved than the average EA, and people with average or below-average involvement were not well-represented. Perhaps this is because the people most likely to experience value drift might also be the least likely to commit to an hour-long interview to talk about value drift, in part because of the stigma attached to value drift in the EA movement. I tried to mitigate this bias by using snowball sampling, in which I asked participants to refer others who had withdrawn from or left the movement entirely. However, only two of the people referred committed to an interview, and both were still substantially involved in the EA movement.

Despite this sample's limitations, because the participants were highly-involved, many of them likely had larger-than-average EA networks and, therefore, they might have had more insight into others' experiences with value drift.

Due to the study’s small sample size, these findings cannot provide definitive evidence on how likely the average EA is to experience value drift. They are, instead, meant to inform what might make someone more or less prone to value drift. However, these results only reflect the experiences of eighteen EAs; more research would be useful to explore whether these results would hold up across the general population.

Perceptions of Value Drift

Three of the eighteen participants sampled felt that they had experienced value drift in the sense of moving away from EA values, but none had left the EA movement entirely. One participant attributed their value drift to conflict with several members of the EA community; the second participant attributed their value drift to burnout; and the third attributed their value drift to a combination of burnout and moving outside of a city with an active EA community.

In general, participants generally did not think they were prone to value drift. Two people acknowledged that their likelihood of experiencing value drift was probably close to the base rate (about 40-50% over five years, based on Joey Savoie’s study and Peter Hurford’s EA Survey post), but nine seemed to think, whether on a gut-level or based on the amount of time they had already been involved, that they were generally unlikely to experience value drift. Because this sample was skewed towards highly involved EAs, these people might have had accurate self-perceptions, if more involved EAs are less prone to value drift. However, they also might have thought they were less likely to experience value drift because of superiority bias or the end-of-history illusion.

Suggestion for EAs: In making decisions where the possibility of value drift might affect the outcome, all else equal, perhaps people should assume that they are more likely to experience value drift than they intuitively think they are.

Factors Influencing Value Drift

In the course of the interviews, I asked participants about

- Why they have experienced value drift (if they’ve experienced value drift)

- Why they might experience value drift in the future

- Why others they know in the EA community have experienced value drift

- Why people in the EA community might experience value drift in general

Below are the most common factors discussed, in order of prevalence. Note that many of these are likely correlated with each other, and some may just be representative of EAs generally rather than people who did not experience value drift.

1. Community and Social Networks

“If I grew up in whatever country lacks any EAs, and all it is is this online community - I don’t know anyone in real life, I’ve never met anyone else who’s an EA - it probably would be a lot harder for me to become as interested in effective altruism... The fact that I can go speak with other people who are interested in the same ideas causes me to become more active in the community.”

Community was the most common theme in these interviews, with fifteen participants stating that losing their connection with the EA community in some way would cause them to stop being an EA. This included:

- Losing their job at an EA org

- Moving outside of an area with a local group or active community

- Experiencing a conflict with individuals in the EA community, or with the beliefs and norms of the EA community as a whole

- The EA community ceasing to exist

This finding aligns with other social research. Connected by Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler discusses how our social networks can actually influence our values on a causal level. For example, if Republican comes into a Democrat’s social circle (or the Democrat’s friend’s social circle, or their friend’s friend’s social circle), the Democrat is more likely to become a Republican as a result. So, having too many non-morally-motivated people in one’s social circle may cause one to experience value drift. Such was the case with one of the participants who experienced value drift.

Suggestion for EAs: For someone trying to avoid value drift, exclusively hanging out with EAs might seem like the obvious thing to do. However, groupthink exists, and tailoring one’s social circles to consist of exclusively people who think exactly like them could be harmful. Still, surrounding oneself with people who are trying to do good in some way or another could help avoid value drift. See the EA Hub’s page on connecting with the EA community for ways to get involved in-person and online.

Suggestion for movement-builders: Finding ways to get EAs connected with other EAs might help minimize value drift in the community as a whole. For example, supporting local EA groups and conferences, maintaining active and welcoming online communities, and facilitating one-on-one connections between EAs (for example, through projects like EA Chats and WANBAM) are all likely useful ways to lessen rates of value drift.

2. Conflicting Values

“I would be happy giving more than [ten percent of my income], but I would not be ok with giving more money for that if I was sacrificing things for my kids. I buy the utilitarian ethics piece, and I’m also selfish. I try to be selfish in ways that are non-harmful, but that’s kind of the balance that I have.”

Twelve participants cited some sort of conflicting value as a reason they, or others, might leave or withdraw from EA. These include:

- Family

- Personal comfort and pleasure

- Other social movements or causes (for example, political movements, religious movements, other causes they care about that aren’t EA-endorsed)

- Social expectations and image

Value drift related to conflicting values involves what I refer to as hierarchical value drift, as it relates to a change in our value hierarchy, as opposed to transformative value drift, which refers to gaining or losing values entirely.

As previously mentioned, our values are, by definition, valuable to us, so discarding all of our other values in favor of EA is likely not useful. But, certain scenarios may temporarily distract us from values higher in our value hierarchy. For example, I might generally think that I value frugality for the sake of giving more to charity, but when my best friends ask me to go on an expensive trip with them, I may become focused on how I value spending time with friends and adventure and temporarily devalue frugality.

Suggestion for EAs: Spending time thinking about our values and perhaps drawing out our value hierarchies separately from these distractions may be useful. Further, setting goals based on our values and creating accountability mechanisms to meet them can help avoid values we want to hold in the long-term (e.g. altruism) from being overrun by values we perceive to be less important (e.g. personal pleasure).

3. Value-Aligned Behavior

“I think that taking more responsibility is sort of - it’s not so much going to activities but actually having to organize them or something like that. It makes you more aligned or more concerned with EA.”

Intuitively, many people think that our values typically influence our actions. However, the opposite may also be true. Some research suggests that our actions influence our behaviors - for example, if I’m volunteering for a cause to fulfill a community service requirement, I’m more likely to think I care about that cause, even if I did not care about it prior to volunteering.

My research supports this. Ten people mentioned engaging with EA content, going to local groups, and being involved in the community in other ways. Though not all of them engage in these behaviors specifically to prevent value drift, most people seemed to think they help prevent value drift. Three people also talked about how being involved in the EA movement helps them feel more aligned with and invested in the movement.

However, I suspect that some of the answers in this area might have been inspired by posts like Darius Meissner’s, so the correlation might not be as strong as it appears from this data.

Suggestion for EAs: Particularly if your career does not directly relate to EA, find ways to get involved in EA. Prioritize making time for this, even if only for a few hours per month.

Suggestion for movement-builders: Creating volunteering opportunities can help EAs become and stay engaged with the movement. It can also help EAs gain useful experience to make them marketable for EA-aligned jobs.

4. Openness to New Ideas

“I’m very open to new ideas and weird ideas. I don’t have a lot of commitment to any strong set of beliefs or something that I feel like can’t be challenged.”

In Some Do Care, Anne Colby and William Damon discuss their interviews with people they found to be “moral exemplars.” One of the themes they found: those who sustained their moral motivation sustained an abstract value of helping others, but their approaches to doing good, previously referred to as concrete values, have changed over time. For example, perhaps someone begins to value doing good through prayer or evangelism, then begins to prioritize through service, then shifts towards valuing social justice activism or systemic change. Throughout, the person continues to care about doing good in the world but is open to new ways to do so.

People in this sample seemed to follow suit - nine participants had changed cause areas at some point in their EA involvement. However, this might just be an EA trait rather than a trait value-stable people hold, as I did not notice a substantial difference here between people who had experienced value drift and people who did not. On the other hand, logically, this makes sense: someone receptive to new ways to doing good might be less likely to give up when the first way does not work or more likely to stay aligned with the movement as it shifts its priorities through new research.

This theme is especially relevant to the EA movement because unlike many social movements, recommendations for concrete actions in the EA movement are likely to change because the nature of EA does not explicitly promote any specific approach to doing good. While, for example, the veganism movement asks people to stop consuming and using animal products, the EA movement simply asks people to use evidence and reason to inform their approach to doing good in the world, and that evidence and reason, and the conclusions that follow, are subject to change. Those who maintain their concrete values, then, may get left behind as the movement shifts its direction. Someone who stays in place may withdraw from the EA community as they realize their concrete values do not align with others in the movement, which, per theme #1 above, could lead them to drift from wanting to do good effectively, or wanting to do good altogether.

Suggestion for EAs: This evidence might suggest that we do not want to avoid value changes in general. Approaching new ideas about ways to do good with curiosity, even if they immediately seem odd or not EA-aligned, may be useful for preventing drift away from altruistic values (though I’m much less certain about this than the other suggestions I’ve mentioned).

5. Sustainability

“I have [experienced value drift], but I think it’s a good thing because I don’t think that I necessarily value EA less so much as I value my health and my sanity a lot more. And part of it is that I’ve come to the extremely obvious but difficult conclusion that it’s really hard to get anything done if you don’t take care of yourself.”

Five participants discussed setting boundaries with EA to stay sustainable. For example, participants discussed:

- Donating less than they could reasonably afford to

- Having friends outside of EA

- Setting aside time to focus on interests, hobbies, and life beyond EA

- Keeping their EA identity small

Burnout was also mentioned as a reason two participants withdrew from the movement, and two other participants mentioned observing burnout in others, though none of the participants mentioned burnout as a reason they might leave the movement in the future. Perhaps this evidence suggests that we underestimate the risk of burnout. However, given that this example has been involved in EA for longer than average, it seems likely that their self-perceptions are accurate and that most, if not all of them had successfully created a lifestyle that was sustainable for them.

However, the law of equal and opposite advice seems relevant here. Many people likely err on the side of caring too much about burnout, and perhaps the average EA would probably benefit from getting more involved rather than less involved. Still, burnout is worth considering, especially for people who know that they tend to overcommit.

Suggestion for EAs: Setting reasonable goals for ourselves is a good first step. New EAs in particular might be tempted to set high goals for themselves without thoroughly considering their time and money constraints. Instead, wait to decide how much you will donate to charity until you’ve looked at your bank account and calculated how much you need to sustain yourself. Wait to decide how much you’re going to volunteer until you’ve figured out how much time you have to give, and consider using time-tracking to avoid the planning fallacy. I also recommend reading the EA Hub’s resources on sustaining an EA lifestyle and Lynette Bye’s interview with Niel Bowerman on striking a healthy balance between productivity and rest.

Also, note that burnout is not solely a consequence of over-working. Burnout is often indicative of a lack of personal fit or a disconnect between expectations and reality. Someone who works 80+ hours a week may not experience burnout if they gain energy from their work, while someone working 20 hours or less might feel burnt out if their work is particularly difficult or stressful for them. If you feel burnt out, take the time you need to recover, but also consider if you can find other ways to be involved in EA that are energizing rather than draining.

Suggestion for movement-builders: Creating a culture in EA organizations and groups that doesn’t glamorize overworking seems important in preventing burnout. Helen Toner’s EAG talk “Sustainable Motivation” has some other useful insights on how to create a work environment conducive to sustainability.

6. Personality

“I’m good at being really committed to something. Also, it just defines me so much. When it’s a very core part of your identity, and you’re getting positive reinforcement by being around a lot of EAs, then it will continue to be part of your identity, I feel like for me it would decrease my utility if I were to abandon this. I would feel purposeless.”

Six people in the sample mentioned that EA made intuitive sense for them or that they had had the goal of making the world a better place as effectively as possible before they encountered the movement. These people seemed to be particularly highly involved and aligned with EA, somewhat more so than people who were initially more skeptical of EA. I suspect that people who find EA intuitive are less prone to value drift than people who do not.

Additionally, four people said that they felt that they had a habit of not experiencing value drift in general. These people generally had a history of being able to set commitments and meet them with little difficulty. For example, one person said that they had previously become vegan immediately after deciding they wanted to, without needing to ease into it as many suggested they should, and had maintained that commitment for several years. Another took the Giving What We Can pledge ten years ago and had maintained their commitment to donating ten-percent of their income.

Suggestion for EAs: Consider whether you have difficulty committing to things or if you held EA beliefs before encountering EA, and use this understanding of yourself to inform your decisions. If you know that you tend to experience value drift and/or have only recently become receptive to EA, you may want to prioritize taking measures to reduce value drift away from EA values. If you know you tend to be value-stable and/or that you have held EA beliefs for a long time, you may want to look into ways to promote positive value changes.

Suggestion for movement-builders: For EA organizations, reaching out to people who are likely to become and stay involved in EA would help create a more sustainable movement. More research to identify who these people might be could be useful.

7. Career

All three of the people who reported experiencing value drift were on earning-to-give paths, though none of these people indicated that their career paths were correlated with experiences with value drift. Further, two participants who were working at EA-aligned organizations said that losing their job might cause them to leave the EA movement in the future, as they would not have as many incentives to pursue EA work. This evidence suggests that people outside of direct work career routes, then, might be more prone to value drift. However, career does not seem to be a particularly strong factor, compared to other factors, based on this sample.

The effects of one’s career on their tendency to experience value drift might also be a result of correlation rather than causation, as people outside of direct work might have less time to connect with other EAs and to commit to getting involved with EA projects. They also might have less relevant career capital in EA priority paths, particularly direct work, if they weren’t immediately receptive to EA, as many people who have some alignment with typical EA values prior to joining EA are also drawn to fields related to doing good in the world such as nonprofit work. Hence, based on themes #1, #3, and #6 mentioned above, those who are earning-to-give may be more prone to value drift.

This sample only including people working with EA and EA-aligned organizations, people in earning-to-give paths, and students, so I cannot say whether people working in academia or politics, for instance, might be more prone to value drift. Further research would be useful to explore the relationship between careers and value drift.

Suggestion for EAs: People on non-EA aligned career paths should perhaps prioritize finding ways to get involved in the community outside of work or moving into 80,000 Hours’ priority paths if it suits their comparative advantage.

Suggestion for movement-builders: EA organizations creating more EA-aligned jobs would likely help keep people from experiencing value drift, though there are other considerations that should be taken into account before prioritizing this (for example, expanding the EA network, influencing organizations not explicitly aligned with EA, and ensuring people outside of direct work benefit from EA community-building efforts).

Future research directions

Value drift, particularly in the context of EA, is a relatively new and neglected area of research. Because of its neglectedness, I think any research in this area has the potential to be highly impactful. I would encourage EAs interested in EA community building, especially those with a social science background, to consider studying the topic.

Some ideas I have about future research directions include:

- Finding literature and/or conducting research on value drift in other social movements (see this post)*

- Replicating this study with improved interview questions and a larger and/or more representative sample

- Surveying EAs about the above-mentioned factors on a larger scale to see if they predict whether people leave EA

- Surveying people’s self-perceptions of their likelihood of leaving EA and comparing them to the rates of how often people actually leave EA

- Interviewing and/or surveying people who have left the EA movement

- Analyzing drop-off numbers among local EA groups

- Conducting longitudinal analyses of values

- Further definition of the term value drift and “drift” more generally

- Philosophical research on moral issues surrounding value drift

*The draft of this post prompted questions about why I haven't discussed research on value drift in other social movements. The term "value drift" is only used in EA and rationalist communities, so research in this area is somewhat difficult to find, as it's not grouped under a single keyword. Research on value changes, recidivism related to moral behaviors (e.g. veg*ism), and drop-off rates in social movements and religions hold some relevance to the topic of value drift, but this research still does not neatly fit into the most narrow definition of value drift. However, if you're interested in doing research in this area, I've collected some possible leads to relevant literature in this area, and I'd be happy to share them with you.

More generally, social research on EA as a social movement is relatively neglected within the community and virtually non-existent in academia. Again, I think there are many opportunities for impact in this area that can also serve as useful career capital for people interested in working at EA organizations in the future.

I’m more than happy to talk further about these results with researchers, EA movement-builders, and others interested in the topic. Feel free to message or email me with questions or to schedule a time to chat: marisajurczyk[at]gmail[dot]com.

Many thanks to Leonard Kahn and Carol Ann MacGregor for advising this project; to David Moss and David Janku for helping me select the topic; to David Moss, Richenda Herzig, and Catherine Low for feedback on interview questions; and to Vaidehi Agarwalla, Michael Aird, David Janku, Michael St. Jules, and Manu Herran for feedback on this post.

Great work! I appreciate how you used formatting and concrete suggestions to adapt this for the Forum

Thank you! :)

This post was awarded an EA Forum Prize; see the prize announcement for more details.

My notes on what I liked about the post, from the announcement:

This was a really interesting read. I had some thoughts reading this bit: "surrounding oneself with people who are trying to do good in some way or another could help avoid value drift."

Specifically it strikes me that there may be a trade-off between preventing value-drift and spreading EA. Hanging out in groups without EA people, and having friends in those groups, is a great way to spread EA values (much in the same way I see families where one person becomes vegetarian / vegan quickly end up with more vegetarians / vegans). So I think it's important to be careful about insulating EAs too much lest EA ideas spread less quickly. That said, spending time with others trying to good in some way (not necessarily EA) is probably optimal for balancing these two concerns.

Thanks! I absolutely agree. I don't think that EAs should surround themselves with only EAs in the name of preventing value drift (this seems borderline cult-like to me), but I think having people in one's social circle who care about doing good, regardless of whether in the EA sense or not, seems like a good idea, for the reason you mentioned, and because I think there are things EAs can learn from non-EAs about doing good in the world.

(Also, non-EAs can make good friends regardless of their ability to contribute to your impact or not. :) )