Most debate week responses so far seem to strongly favor animal welfare, on the grounds that it is (likely) vastly more cost-effective in terms of pure suffering-reduction. I see two main ways to resist prioritizing suffering-reduction:

(1) Nietzschean Perfectionism: maybe the best things in life—objective goods that only psychologically complex “persons” get to experience—are just more important than creature comforts (even to the point of discounting the significance of agony?). The agony-discounting implication seems implausibly extreme, but I’d give the view a minority seat at the table in my “moral parliament”.[1] Not enough to carry the day.

(2) Strong longtermism: since almost all expected value lies in the far future, a reasonable heuristic for maximizing EV (note: not the same thing as an account of one’s fundamental moral concerns) is to not count near-term benefits at all, and instead prioritize those actions that appear the most promising for creating sustained “flow-through” or “ripple” effects that will continue to “pay it forward”, so to speak.

Assessing potential ripple effects

Global health seems much more promising than animal welfare in this respect.[2] If you help an animal (especially if the help in question is preventing their existence), they aren’t going to pay it forward. A person might. Probably not in any especially intentional way, but I assume that an additional healthy person in a minimally functional society will have positive externalities, some of which may—like economic growth—continue to compound over time. (If there are dysfunctional societies in which this is not true, the ripple effect heuristic would no longer prioritize trying to save lives there.)

So if we ask, which cause area is such that marginal funding is most likely to positively effect the future beyond our immediate lifetimes?, the answer is surely global health over animal welfare.

But that may not be the right question to ask. We might instead ask which has the highest expected value, which is not necessarily the same as the highest likelihood of value, once high-impact long-shots are taken into account.

Animal welfare efforts (esp. potentially transformative ones like lab-grown meat) may turn out to have beneficial second-order effects via their effect on human conscience—reducing the risk of future dystopias in which humanity continues to cause suffering at industrial scale. I view this as unlikely: I assume that marginal animal welfare funding mostly just serves to accelerate developments that will otherwise happen a bit later. But the timing could conceivably matter to the long-term if transformative AI is both (i) near, and (ii) results in value lock-in. Given the stakes, even a low credence in this conjunction shouldn’t be dismissed.

For global health & development funding to have a similar chance of transformative effect, I suspect it would need to be combined with talent scouting to boost the chances that a “missing genius” can reach their full potential.

That said, there’s a reasonable viewpoint on which we should not bother aiming at super-speculative transformative effects because we’re just too clueless to assess such matters with any (even wildly approximate) accuracy. On that view, longtermists should stick to more robustly reliable “ripple effects”, as we plausibly get from broadly helping people in ordinary (capacity-building) ways.

Three “worldview” perspectives worth considering

I’ve previously suggested that there are three EA “worldviews” (or broad strategic visions) worth taking into account:

(1) Pure suffering reduction.

(2) Reliable global capacity growth (i.e., long-term ripple effects).

(3) High-impact long-shots.

Animal welfare clearly wins by the lights of pure suffering reduction. Global Health clearly wins by the lights of reliable global capacity growth. The most promising high-impact long-shots are probably going to be explicitly longtermist or x-risk projects, but between animal welfare and ordinary global health charities, I think there’s actually a reasonable case for judging animal welfare to have the greater potential for transformative impact on current margins (as explained above).

I’m personally very open to high-impact long-shots, especially when they align well with more immediate values (like suffering reduction), so I think there’s a strong case for prioritizing transformative animal welfare causes here—just on the off chance that it indirectly improves our values during an especially transformative period of history.[3] But there’s huge uncertainty in such judgments, so I think someone could also make a reasonable case for prioritizing reliable global capacity growth, and hence global health over animal welfare.[4]

- ^

To help pump the perfectionist intuition: suppose that zillions of insects experience mild discomfort, on net, over their lifetimes. We’re given the option to blow up the world. It would seem incredible to allow any amount of mild discomfort to trump all complex goods and vindicate choosing the apocalypse here. (I’m not suggesting that we wholeheartedly endorse this intuition; but maybe we should give at least some non-trivial weight to a striving/life-affirming view that powerfully resists the void across a wider range of empirical contingencies than Benthamite utilitarianism allows.)

- ^

I owe the basic idea to Nick Beckstead’s dissertation.

- ^

But again, one could likely find even better candidate long-shots outside of both global health and animal welfare.

- ^

It might even seem a bit perverse to prioritize animal welfare due to valuing the “high impact long shots” funding bucket, if the most promising causes in that bucket lie outside of both animal welfare and global health. If we imagine the question bracketing the “long shots” bucket, and just inviting us to trade off between the first two, then I would really want to direct more funds into “reliable global capacity growth” over “pure suffering reduction”. So interpreting the question that way could also lead one to prioritize global health.

Why? Each bednet costs 5 $, and Against Malararia Foundation (AMF) saves one life per 5.5 k$, so 1.1 k bednets (= 5.5*10^3/5) are distributed per life saved. I think each bednet covers 2 people (for a few years), and I assume half are girls/women, so 1.1 k girls/women (= 1.1*10^3*2*0.5) are affected per life saved. As a result, population will decrease if the number of births per girl/women covered decreases by 9.09*10^-4 (= 1/(1.1*10^3)). The number of births per women in low income countries in 2022 was 4.5, so that is a decrease of 0.0202 % (= 9.09*10^-4/4.5). Does this still seem implausible? Am I missing something?

That is one hypothesis advanced by the author, but not the only interpretation of the evidence? I think you omitted crucial context around what you quoted (emphasis mine):

My interpretation is that the author thinks the effect on total fertility is unclear. I was not clear in my past comment. However, by "lifesaving interventions may decrease longterm population", I meant this is one possibility, not the only possibility. I agree lifesaving interventions may increase population too. One would need to track fertility for longer to figure out which is correct.

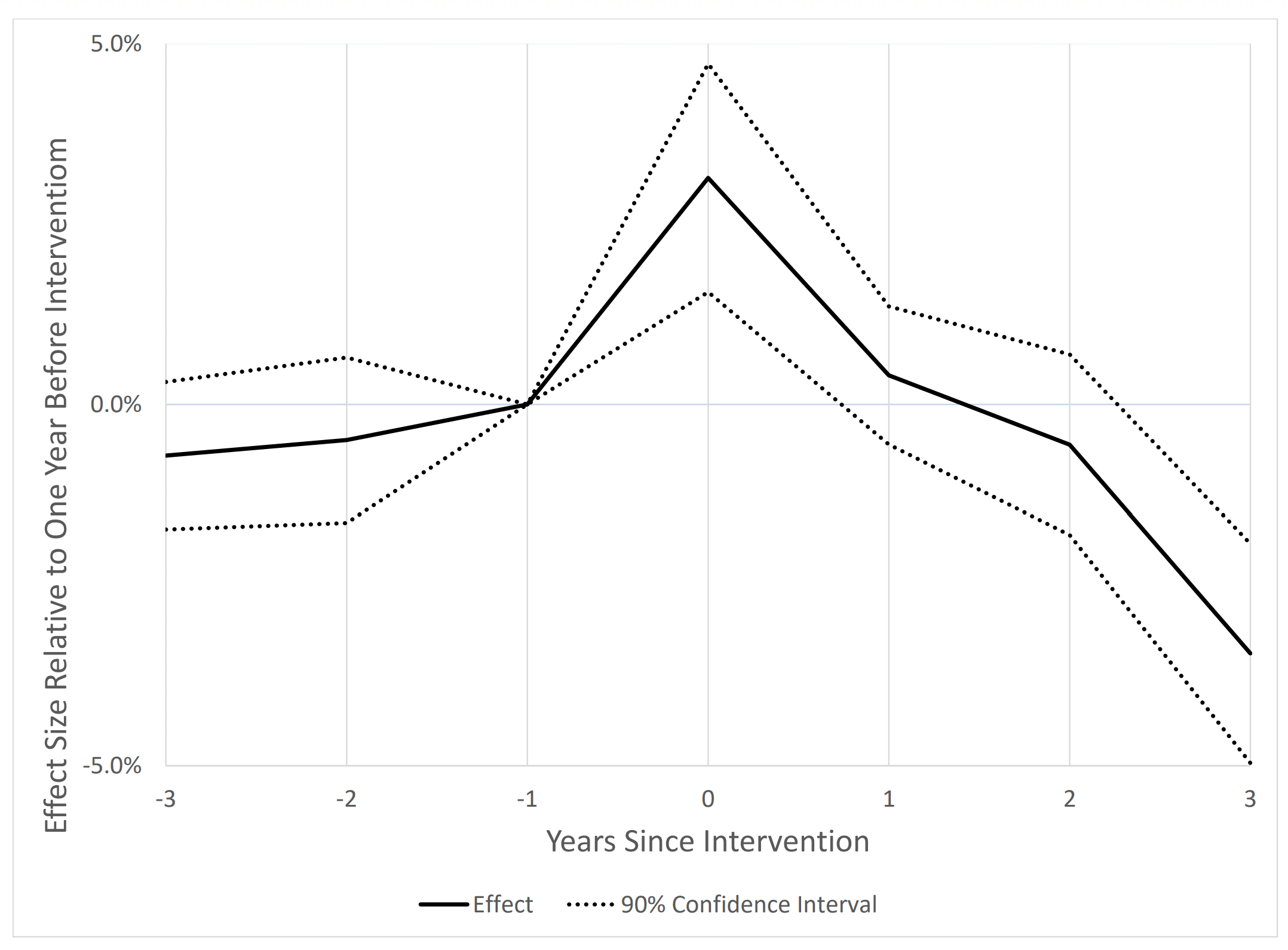

From Figure 6 below, there is a statistically significant increase in fertility in year 0 (relative to year -1), and a statistically significant decrease in year 3. Eyeballing the area under the black line, I agree it is unclear whether total fertility increased. However, it is also possible fertility would remain lower after year 3 such that total fertility decreases. Moreover, the magnitude of the decrease in fertility in year 3 is like 3 % or 4 %, which is much larger than the minimum decrease of 0.0202 % I estimated above for population decreasing. Am I missing something? Maybe the effect size is being expressed as a fraction of the standard deviation of fertility in year -1 (instead of the fertility in year -1), but I would expect the standard deviation to be at least 10 % of the mean, such that my point would hold.