Epistemic Status: Uhhhhhh.

Intro

I think longtermists sometimes fail to grapple with animal welfare, and even when we do, the arguments leave something to be desired in the way of nuance. For example, I have encountered claims like "there will be no animals in the future!" or "moral circle expansion solves!" which strike me as shallow dismissals of an important question.

In this post, I'm interested in identifying some empirical questions about animal welfare that bear on how bad AI doom would be. I focus on wild animals because I think their welfare probably controls the question of how good the world is at present.

Variables

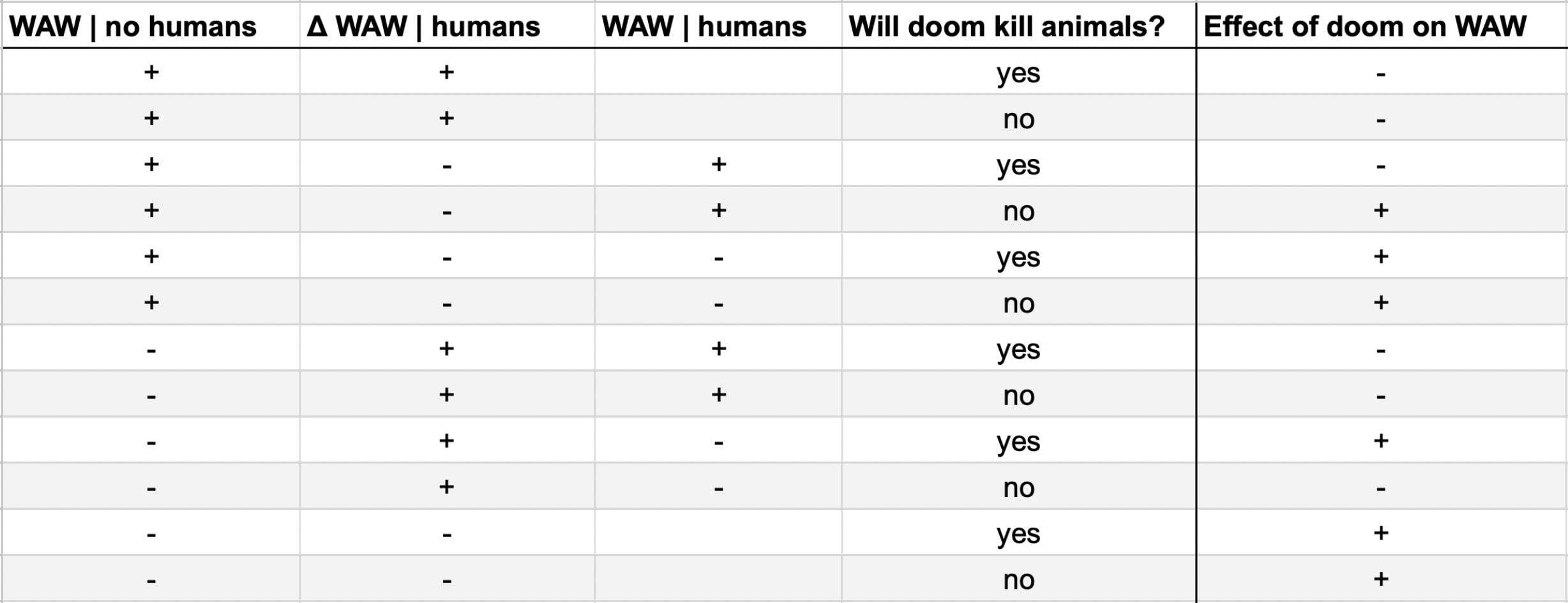

For our model, suppose doom is a discrete event that could occur at a fixed time in the future and would eliminate all humans. All events up to doom are considered sunk; we are concerned with what happens post-doom. Here are some variables to consider:

WAW | no humans: If wild animals survive AI doom, do they lead good lives, on net? To first order, this is True iff wild animals lead good lives now, which is a fraught ethical problem. Wild animals are subject to predation, disease, starvation, injury, and disease, and many die before reaching adulthood. On the other hand, much of an animals life consists of some state of preference-satisfaction, which might outweigh the preceding sources of pain. (Of course, sharing the world with AGI introduces complications for wild animals that are not captured by their current welfare levels.)

Δ WAW | humans: Suppose humans do survive (no doom). Do they improve or frustrate wild animal welfare compared to the baseline with no humans? In the optimistic camp, we find arguments like moral circle expansion, which holds that humans will benefit wild animals through interventions like planting soy worms for the birds or whatever. In the pessimistic camp lives the conventional litany of ways that humans seem to hurt wild animals (deforestation, hunting, pollution, etc).

WAW | humans: Accounting for the effects of sharing a doomless world with humans, do wild animals lead good lives? In other words, is the above delta large enough to flip the sign of animal welfare from negative to positive or vice versa? For example, maybe wild animals would suffer in a world without humans, but humans stand to make positive contributions to wild animals such that they would lead net-good lives.

Will doom kill animals? For simplicity, if True, doom spells the end for every wild animal. If False, there will be roughly no longterm change in the wild animal population due to doom. Note that animal doom would probably involve pain but I'm ignoring this because it's unclear if doom-death is more painful than a counterfactual death, and even if it is, this greater marginal pain would be negligible compared to the long run impact of, e.g., averted suffering. Some doom scenarios seem to imply wild animals' extinction (AGI needs those sweet, sweet atoms), but I think it's often unclear, which reflects the poor state of Animal x Longtermist discourse. Is the elimination of wild animals a convergent instrumental subgoal in its own right? Or would animal extinctions occur incidentally in pursuit of human extinction?

Outputs

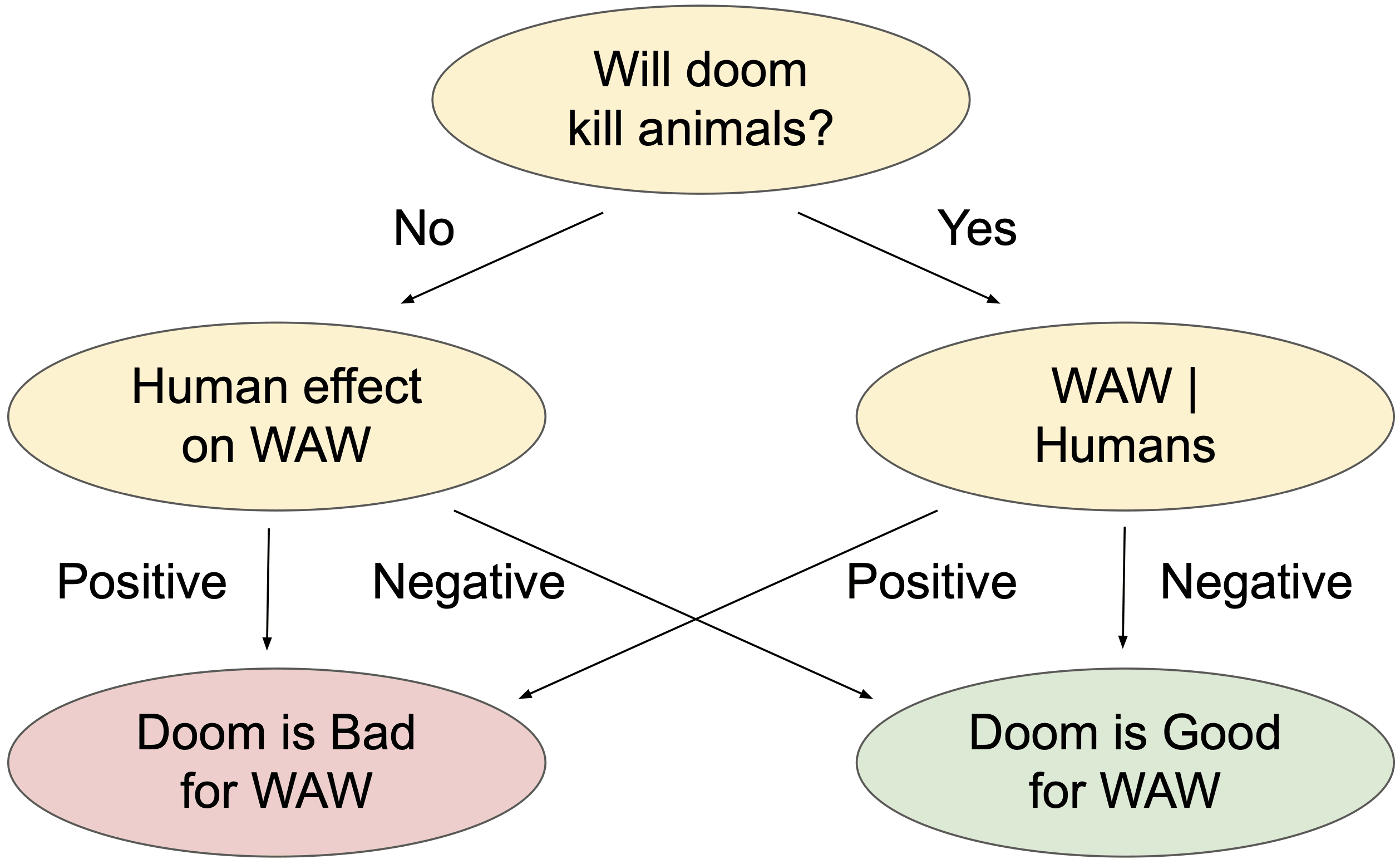

From these four inputs, we are interested in whether doom is good or bad for wild animals:

If doom would kill animals, the effect of doom is the opposite of WAW | humans (would animals be better off disappearing along with humans?). Otherwise, the effect of doom is the opposite of Δ WAW | humans (would animals be better off without humans?).

Observe that there are an equal number of scenarios for which doom is good as bad. I would be interested in hearing probability distributions over these cases in the comments, especially ones that make more crisp my understanding of whether doom would eliminate wild animals.

I think it's worth explicating some of these scenarios. The others are left as an exercise to the reader ;)

Scenarios

Shepherdless Sheep (row 2, 8, 10): Wild animals would have benefited from humans, but instead they are adrift in the world (leading good or bad lives, depending on the case). We should avoid doom so we have a chance to populate the planet with better-off wild animals.

Animal Liberation (row 4, 6): In the presence of humans, wild animals would be worse off, but in the absence of humans, they are quite content. Doom is good because it frees animals from humans.

Misery Putter-Outer (row 5, 9, 11, 12): Humans either make things worse or don't help enough. Doom presents a merciful end to wild animal suffering.

Closing

I'm not trying to be contrarian; once you account for the impact on humans, Doom is probably, like, bad. But I do wish people attended more carefully to other moral patients in their arguments about AI doom.

I think the easy way to avoid these debates is to outweigh wild animals with digital minds. I'm receptive to this move, but I would like to see some estimates comparing numbers of wild animals vs potential for digital sentience. I also think this argument works best if alignment research will afford some tractability on the quantity of digital minds or quality of digital experiences, so I would be interested to hear about work in this direction.

Thanks for this analysis, utilistrutil!

Agreed. For reference, I estimated the scale of the welfare of wild and farmed animals is 50.8 M and 4.64 times that of humans.

Fai also has (relevant!) thoughts on the intersection between animal welfare and longtermism.

Thanks for the references! Looking forward to reading :)