Lack of access to family planning is a widespread problem with harmful consequences for health, economic well-being, and other outcomes. Despite its importance, it is comparatively neglected by EAs. Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) proposes to tackle this problem by launching a new nonprofit that would provide postpartum family planning counseling in priority countries. Contact us at ula@charityentrepreneurship.com if you’re interested in getting involved, or apply to our 2021 Incubation Program (deadline: April 15, 2021).

1. Why family planning?

Each year, over 300,000 women die from pregnancy-related causes. Maternal mortality is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa, with two-thirds of all maternal deaths in 2015. A higher number of births per woman is also strongly associated with higher rates of child mortality. Short-spaced pregnancies, in particular, pose a greater risk to both mother and child.

There are over 120 million unintended pregnancies each year. Data from the UN shows that 10% of all women of reproductive age worldwide have unmet needs for family planning, meaning that although they do not want to fall pregnant, nor are they using contraception. Unmet family planning needs are particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa.

Health isn’t the only casualty of inadequate family planning. Lack of access to family planning impacts a whole range of outcomes, from education and economic wellbeing to climate change. The supplementary report for our cost-effectiveness analyses discusses these in more depth and explains how we modeled them. Depending on how you consider flow-through effects, we believe that this area could be as effective or more so than direct delivery health interventions.

Due to its importance, family planning receives a good amount of attention in terms of both research and availability of (often counterfactually strong) funding. However, it remains neglected in two important ways. Despite extensive research into the barriers to family planning, little prioritization work has been done. Additionally, family planning is a less common cause area of focus among applicants to the CE Incubation Program.

To address the lack of prioritization work, Charity Entrepreneurship has conducted hundreds of hours of research to compare interventions and identify the most impactful. Progressive stages of our extensive research process whittled down to two recommended charity ideas for family planning: mass media campaigns and postpartum family planning. These top ideas are highly cost-effective, with strong evidence of impact.

Prioritization is an important first step, but to realize the change we need implementation. In 2020, Kenneth Scheffler and Anna Christina Thorsheim launched Family Empowerment Media, working on mass media campaigns. They recently launched their proof of concept campaign with two radio stations in Kano State in Nigeria, and are reaching around 2.5-3 million beneficiaries. Through Charity Entrepreneurship’s 2021 Incubation Program, we hope to launch the second of our top family planning ideas – postpartum family planning.

2. Why postpartum family planning?

2.1 The intervention

The period up to ~24 months after a woman has given birth (i.e. the postpartum) is a crucial time for family planning. A new charity would help integrate family planning counseling services into postpartum care, providing training and support to health workers.

Becoming pregnant soon after giving birth risks the health of both mother and child, yet the data show that contraceptive use among postpartum women is lower than average. Contributing factors include misconceptions around how quickly a woman returns to fertility after giving birth and stigma surrounding contraception use. Compounding the issue, family planning is frequently not offered during postpartum care. Yet many women are only in contact with the healthcare system during pregnancy and delivery, which makes this a particularly good opportunity to discuss family planning options.

We estimate that each year, 23 million postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa are not using contraception. Surveying 22 LMIC countries, Moore et al. (2015) found that over half of pregnancies occur at too-short intervals in 9 countries.

Conversations with experts and our survey of the evidence base (detailed below) highlighted that the immediate postpartum is the optimal time for family planning counseling. As an add-on, broaching the topic during antenatal care can ensure that a woman has the time to weigh her options and discuss her decision with her partner.

This intervention would be most effective in countries where contraception is available, but misinformation prevents uptake. Based on our analysis, Senegal and Ghana look to be particularly promising countries; Benin, Sierra Leone, and Cameroon also hold promise.

A new charity would begin by establishing relationships with local nonprofit and public actors. This would allow them to build their knowledge of the context and work on their proof of concept. Contextual knowledge is key to understanding the barriers to contraception uptake, so working with local stakeholders and being immersed in the context will be essential for a new charity. In the longer term, the charity would achieve scale by partnering with the local government.

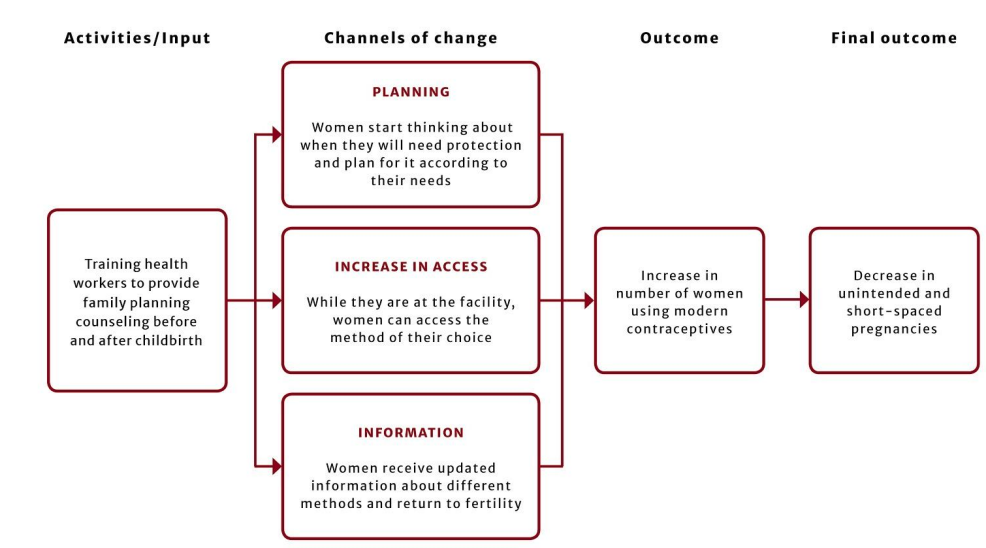

Below is a theory of change for this new nonprofit:

2.2 Evidence & cost-effectiveness

This spreadsheet summarizes the nineteen studies on postpartum family planning, including eight RCTs and two systematic reviews. Find more discussion of the evidence of effectiveness for this intervention in section 5.3 of our report.

Based on the evidence, we estimate a 4.7 percentage point increase in uptake of contraceptives. This spreadsheet contains our cost-effectiveness analysis. The main impact we sought to capture was the cost per unintended birth averted: we found that postpartum family planning would cost as little as $67. We discuss why we chose to measure cost-effectiveness in unintended births in our supplementary report.

In addition to unintended births averted, we quantified cost-effectiveness in terms of DALYs, income effects, contraceptive uptake, CO2 emissions, and welfare points. We also calculated cost-effectiveness when including counterfactual considerations for donor funding, government resources, and the nonprofit’s co-founders. Based on our analysis, this intervention is cost-effective from multiple perspectives.

This overview table displays our cost-effectiveness estimates for the various factors we considered:

| Unit | $ cost per unit |

| Additional user of contraception | 39 |

| DALY averted | 984 |

| Unintended birth prevented | 67, or 144 if counterfactuals included |

| Tonnes of CO2 averted | 0.33 (3 tonnes per $ spent) |

| Welfare points | <0.003 (377 WP per $ spent) |

| Dollar generated in income benefits | <0.01 ($105 per $ spent) |

3. How you can help

We’re keen to connect with aspiring entrepreneurs, so if you know anyone who might be interested, please share this post. Further details about the Incubation Program can be found on our website (apply by April 15). Feel free to contact us for more information at ula@charityentrepreneurship.com.

I'm quite concerned about your cost-effectiveness analysis. It seems to have been done in a quite naive way that massively biases the conclusions.

When we do cost-benefit analysis, we need to consider both the costs and the benefits. Yet while your analysis and spreadsheet describe at length the costs of new people (financial, environmental etc.), it does not seem to analyse the benefits at all.

This would not be a big deal if these benefits were small. But they are actually very large!

Firstly, there are a lot of benefits to existing people from larger population sizes:

It is of course possible that these benefits might be outweighed by the costs outlined in the report. But we cannot simply assume that this is the case. As far as I can see the spreadsheet does not contain any reference to these considerations, and the report contains only a single throw-away sentence under 'other effects we did not research'.

But even more importantly, there is a huge class of people whose interests are closely tied to future population growth: those future people! As life is good for most people, this is a major advantage. They get to experience the joys of playing and growing and love and all the other good things in the world. I think the vast majority of people in the world live good lives and do not regret being born, so this is a massive positive.

Now, some people adopt ethical views according to which future people do not count. I, along with many academic philosophers and other EAs, reject such views, but they definitely exist, and to the extent that you had credence in such views this would reduce the benefits of population increases.

However, this report does not seem to endorse such a view, because it looks at the animal welfare implications of incremental people's entire lives - even though most of these animals have not yet been born, and indeed might never exist at all. Similarly, it considers the health benefits to newborns who have not yet been conceived. And it talks about the impacts of climate change - impacts which largely fall on future people. Given these discussions of the costs to future people/animals, it seems hard to justify not even mentioning the benefits of existence for future people.

Indeed, such concerns were actually mentioned on the CE website in the past:

Despite this, these considerations did not seem to make it into the report - even in the 'Limitations' or 'Other effects' sections.

(And of course, even if you did reject such totalist views, the instrumental benefits of larger populations for existing generations would remain.)

As such, I would strongly encourage you to re-visit the analysis and try to incorporate both the costs and the benefits of the policy. Given the excellent work CE has done on other issues I would not want to see such an omission risk potentially promoting a negative expected value program.

Hey Larks, thanks for the great comment. I think it gets at some key assumptions one has to consider when evaluating this as an intervention. We didn’t end up going into that in this post, but happy to cover it below.

I both see the scenario in which the benefits outweigh the costs (the one in which we are happy to incubate this charity), and I also see scenarios where the costs are higher than the benefits (in that case we wouldn't recommend it). Specifically:

When you consider the context of the families that an intervention such as this would be impacting I think the benefits you layed out are a lot smaller (to the point they do not largely change the calculation). They are typically families with large family size (my expectation is that the 4th child or grandchild does not carry the same weight as the first, particularly when it comes to long term support of the family).

They are also typically in low-income jobs with limited specialization (often family planning is most needed in families earning income from primary agriculture). I expect that averting unwanted pregnancy frees up the income of the household to spend on the current family, e.g. on more education opportunities or a more nutritious diet that has further positive flow-through effects on the family. I think this same education confounder also cross-applies to creating more artists and scientists. It's not at all clear to me that net higher population vs higher average education but smaller families would result in this.

Although I have some sympathy for the economies of scale arguments, I think depending on the country the efficiency effects of having a very young or rapidly growing population trade off against this in quite an unfavourable way. I also think there are less economies of scale in less connected and more rural settings. (E.g. things like electricity or water have limited scale in these locations.) I also expect these benefits to be quite small relative to the current factors we consider.

When we are modelling cost-effectiveness on that sheet we are not aiming to take into account all of the externalities, but rather compare between interventions within family-planning, so you probably won’t find them there. We would use a different methodology to take them into account. But I take your point about the broader cost-benefit considerations.

I do think you have hit on the really key assumption that can change one’s model of family planning though. “Life is good for most people”. We spend a considerable amount of time and work thinking about it and I agree that there is a lot of moral and epistemic uncertainty around the issue. It is probably the hardest thing to take into account when it comes to the assessment of moral weights of various outcomes. Depending on how one takes it, it can either result in 60 years equivalent of utility or disutility. However, I think again we have to look at the population very closely. Populations that do not have access to family planning information or counselling are more likely to have lower happiness levels. The country our last family planning charity chose to work in is Nigeria, where the average happiness goes up and down between 5 and 6 out of 10. Another country we recommend is Senegal, where the numbers are even lower. But I would say even this data is not precise enough as even within countries populations without access to family planning are typically far lower income than average. Also, the child whose existence would be prevented would be a child the family would prefer not to have, and this seems likely to have an effect on the average happiness of both the child and the family. We know the SD of happiness in Nigeria is pretty large ~2.5 (this variation is also typical across other locations). It's hard to know exactly what happiness that person would have over their life. It could easily be in the 3-4/10 range. If you think a year lived at 3-4 is net positive and something you would want to create more of, then indeed this is a huge factor against family planning. If you think its net negative then its a huge factor in favour. I think this is one of the key ethical questions. It comes down a lot more to do with positive vs negative leaning utilitarianism and how you view various weightings of subjective well being. This is a factor we considered a lot when thinking about it and although I think there are defendable different perspectives our team generally came down on the side of this effect being a net positive for family planning (some more info here).

I do think we could have made improvements to the report to make some of these judgement calls more clear and bring people's attention to the factors that affect the analysis significantly. We do tend to discuss these considerations and outline when the results of the general judgement about family planning may differ according to some ethical or empirical differences in much greater depth with incubatees who are considering working in these areas and it’s indeed a complex issue, because of this we have typically found it it easier to discuss it in conversation rather than in writing. I agree that the report could have been better written to take that into account.

Seems you're implying that life is net-good for most people globally? Do you have a source for this as I always assumed the opposite (but would love to be proven wrong)?

Hi James,

I did a short analysis on this where I conclude around 6 % of people have negative lives.

The above neutral point is based on section “How Many People Have Positive Wellbeing?” of Chapter 9 of What We Owe the Future (WWOF) from William MacAskill:

Larks, as much as you consider the provided cost-benefit analysis to be "naive", I am afraid the same applies to several of the counter-points you mentioned. Could you please give some sources that support (a) your claims and (b) are broadly generalizable or generalizable to a degree they should support policy? Specifically, I think some of your assumptions you just take as given even though there is a lot of high-quality evidence to the contrary. I was also a bit disappointed that you did not want to answer on the below issues when you made that identical post the first time around. It seems to me like it is informed by an inherent pro-natalist view without the proper analysis of underlying issues and well-established complexities to the contrary. For the four bullet points in your post, I would like to provide counter-arguments (which I would be happy to discuss if you're interested) why they might not be correct and would greatly appreciate if you could provide generalizable evidence supporting your bullet points:

What is the EV here? Does this scale linearly with the amount of people that come into existence? Do you have any sources for the amount of "additional happiness" vs "additional suffering" caused by these humans to other life-forms (cf. average global meat and fish consumption)? There are various studies that basically say that the relation between "children" and "happiness" is complicated at the very least, for example seen in the following articles. All in all, happiness for parents mostly decreases while they actively rear children, for example:

This depends on the kind of growth and whether the government and economy of a country with a growing population can adequately supply all these points you mentioned. Many countries only experience a real bump in development due to the Demographic Dividend, i.e. when birth rates fall (s. for example Johns Hopkins University and Wikipedia). In many countries, unsustainable population growth depletes financial resources of governments and prevents long-term strategic investments by tying budgets to short-term social support. The same applies to families: Family income only increases with more family members once these new family members reach working age. Before that, they do not have more, but less money to spend on the individual, including education and training. In other words: Growth in population is not good for a country per se. It needs to be sustainable and supportable (by government and family budgets) for a country and its population to profit. Many countries such as Rwanda only really developed once they managed to profit from the Demographic Dividend, as established in countless peer-reviewed articles.

This only holds true if the society that grows can provide adequate education opportunities to support the specialization you mentioned. Good counter-examples to your argument are, in fact, the fastest-growing populations we know: Sub-Saharan countries. If your argument was generally true, countries such as South Sudan, Angola, Malawi, Burundi, Uganda, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali should experience greater degrees of professional specialization. Do you have any evidence to support this? I would be very happy to see it!

Do you have any studies here that show the likelihood of people in the fastest-growing societies by birth numbers becoming inventors or scientists?

The scientific publication that has received the most supportive signatures from scientists ever, the World Scientists' Warning To Humanity, specifically urges world leaders to reduce human population growth. Quoting from Wikipedia which provides the primary source:

The Second Notice specifically states:

Do you think that this notice is generally biased or naive?

Hi Ula,

thank you for your post and I am very happy to see this being worked on!

Family planning services and providing unmet contraception needs are, in my opinion, great interventions to pursue. Not only for the immediate effects on the women affected, but also on poverty outcomes (at the individual level, family level, and country level), for enabling countries to profit from the Demographic Dividend, and for reducing total human activity footprint and resource needs locally and globally. As you stated, it also has positive effects on farmed and wild animal suffering. All in all, every dollar spent on preventing unintended pregnancies has several positive downstream effects on cause areas like climate change, poverty and animal suffering.

What I found very interesting to read was the focus on the post-partum period. Given your explanation that seems like a good time to approach the issue. Do you know of other organizations that follow this approach, given your point that this is one of the few times a woman will come in contact with the health system?

Also, your estimate for the cost of one tonne of CO2 averted (3 tonnes per USD spent or 0.33 USD per tonne of CO2 averted) would place your intervention among some of the most cost-effective for climate change. Is this generalizable to family planning in general and, if so, how? The Coalition for Rainforest Nations places their estimates between 0.12 and 0.72 USD per tonne, and Founder's Pledge assume somewhere in the range of 0.24 to 2.60 USD per tonne for CfRN's past work; Clean Air Task Force's range is between 0.10 to 1.00 USD per tonne of CO2 according to the same Founder's Pledge report. In general, though, there are many interventions targeting climate change that are much less cost-effective. That means that, just if targeting climate change alone, your proposed intervention would already be very effective, but it additionally also has positive effects on other targets like poverty and animal suffering. In countries with even higher resource use (animal products, land, CO2 emissions) this should lead to even bigger effects.

That leads me to think that family planning and fulfilling unmet contraceptive needs would generally be a very effective intervention to support for multiple outcomes. What is your view on that? Is this generalizable to other countries or not?

Hi Rafael,

Thanks for your thoughtful response – it’s great to hear your impressions on our research!

"Do you know of other organizations that follow this approach, given your point that this is one of the few times a woman will come in contact with the health system?"

The expert view section of our report (p. 16) has the most information about other actors in the space. Key points:

"Your estimate for the cost of one tonne of CO2 averted (3 tonnes per USD spent or 0.33 USD per tonne of CO2 averted) would place your intervention among some of the most cost-effective for climate change. Is this generalizable to family planning in general and, if so, how?… That leads me to think that family planning and fulfilling unmet contraceptive needs would generally be a very effective intervention to support for multiple outcomes. What is your view on that? Is this generalizable to other countries or not?"

In the specific case of family planning, CE is uncertain but optimistic that family planning and fulfilling unmet contraceptive needs can be impactful on a range of outcomes. However, we don’t think that CEAs should be taken at face value and are very uncertain of the true effect on climate change. More in-depth work is needed to estimate the effect. You can read more about our thoughts in our blog post on why we chose to research family planning. Project Drawdown also has a nice summary. The organization Having Kids is also doing some work that might interest you.

Founders Pledge has previously analyzed the effect of lifestyle changes that could affect the climate and looked into “having one fewer child”. The results change dramatically depending on whether or not you account for policy changes leading to reductions in future generations’ emissions.

All that to say, we would be cautious about generalizing more broadly, and would not expect the same numbers to apply. This is also why for example we discount studies that take place in different contexts when examining the evidence for a particular intervention: generalizations get messy.

As a quick example for how generalizations about family planning and climate change can get tricky: per capita emissions are much higher in first world countries than in developing contexts, but fertility rates (i.e. the average number of children born to each woman) are much lower. If we want to compare the two, we need to account for these and many other such differences. CE hasn’t looked into this question in depth, although our implementation report (which we share with co-founders) lists a couple more countries in addition to Ghana and Nigeria as potentially promising.

We hope that helps answer your questions! Thanks again for engaging with our research. :)