(...but also gets the most important part right.)

(Context: I'm Max Harms, alignment researcher at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. This is a cross-post from Less Wrong.)

Bentham’s Bulldog (BB), a prominent EA/philosophy blogger, recently reviewed If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. In my eyes a review is good if it uses sound reasoning and encourages deep thinking on important topics, regardless of whether I agree with the bottom line. Bentham’s Bulldog definitely encourages deep, thoughtful engagement on things that matter. He’s smart, substantive, and clearly engaging in good faith. I laughed multiple times reading his review, and I encourage others to read his thoughts, both on IABIED and in general.

One of the most impressive aspects of the piece that I want to call out in particular is the presence of the mood that is typically missing among skeptics of AI x-risk.

Overall with my probabilities you end up with a credence in extinction from misalignment of 2.6%. Which, I want to make clear, is totally fucking insane. I am, by the standards of people who have looked into the topic, a rosy optimist. And yet even on my view, I think odds are one in fifty that AI will kill you and everyone you love, or leave the world no longer in humanity’s hands. I think that you are much likelier to die from a misaligned superintelligence killing everyone on the planet than in a car accident. … So I want to say: while I disagree with Yudkowsky and Soares on their near-certainty of doom, I agree with them that the situation is very dire. I think the world should be doing a lot more to stop AI catastrophe. I’d encourage many of you to try to get jobs working in AI alignment, if you can.

What a statement! It would be a true gift for more of the people who disagree with me on these dangers to have the sobriety and integrity to acknowledge the insanity of risking this beautiful world that we all share.

Alas, I can’t really give BB’s review my blanket approval. Despite having some really stellar portions, it does not generally clear my bar for sound reasoning, both in that it demonstrates many invalid steps, and includes some outright falsehoods. (In BB’s defense, he has readily acknowledged some such issues and updated in response, which is a big part of why I’m writing this.) Most of this essay will be an in-depth rebuttal to the issues that I see as most glaring, with the hope that by converging towards the truth we will be better equipped to address the immense danger that we both think is worthy of addressing.

Confidence

Bentham’s Bulldog acknowledges that he is taking a somewhat extreme position. He acknowledges that there are many reasons to be more concerned than he is, including:

The future is pretty hard to predict. It’s genuinely hard to know how AI will go. This is an argument against extreme confidence in either direction—either of doom or non-doom.

Despite this, he is more extreme in his confidence that things will be ok than the average expert, and vastly more confident than a lot of people he respects, such as Scott Alexander and Eli Lifland.

In many places in his review he criticizes the authors of IABIED as overconfident, and criticizes the book as not making the case that extreme pessimism is warranted. I think this is a basic misunderstanding of the book’s argument. IABIED is not arguing for the thesis that “you should believe ‘if anyone builds superintelligence with modern methods, everyone will die’ with >90% probability”, which is a meta-level point about confidence, and instead the thesis is the object-level claim that “if anyone builds ASI with modern methods, everyone will die.”

Yes, Yudkowsky and Soares (and I) are very pessimistic, but that pessimism is the result of many years of throwing huge amounts of effort into looking for solutions and coming up empty-handed. IABIED is a 101-level book written for the general public that was deliberately kept nice and short. I kinda think anyone (who is not an expert) who reads IABIED and comes away with a similar level of pessimism as the authors is making an error. If you read any single book on a wild, controversial topic, you should not wind up extremely confident![1] To criticize an idea on the grounds that the evidence for that idea isn’t conclusive is insane — that’s a problem with your body of evidence, not the ideas themselves!

If the idea is to critique the book on the grounds that the authors have demonstrated their irrationality by being confident (though arguably[2] less confident than BB![3]), I want to point out two things. First, that this is an ad-hominem that doesn’t actually bear on the book’s thesis. More importantly, that BB has approximately no knowledge of the experiences and priors that led to those pessimistic posteriors. In general I think it’s wise to stick to discussing ideas (using probability as a tool for doing so) and avoid focusing on whether someone has the right posterior probabilities. This is a big part of why I detest the “P(doom)” meme.

But as long as criticizing overconfidence is on the table, I encourage Bentham’s Bulldog to spend more time reflecting on whether his extreme optimism is warranted. I don’t want BB to update to my level of confidence that the world is in danger. I want him to think clearly about the world that he can see, and have whatever probabilities that evidence dictates in conjunction with his prior. But my sense is that according to his own lights, he should be closer to Toby Ord than to the average thinker.

The Multi-stage Fallacy

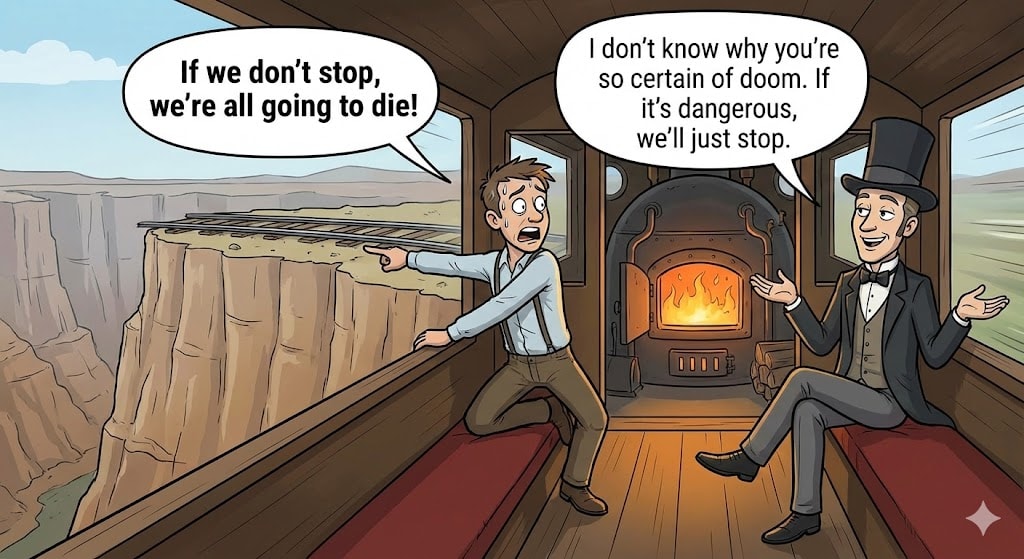

The central reasoning structure that leads BB to being very optimistic is breaking the AI-doom argument into 5 stages, assigning a probability to each stage, multiplying them together and getting a low number.

Even if you think there’s a 90% chance that things go wrong in each stage, the odds of them all going wrong is only 59%. If they each have an 80% chance, then the odds of them all happening is just about one in three.

This sort of reasoning is so infamous in MIRI circles that Yudkowsky named it “the multiple stage fallacy” ten years ago. And BB is even aware of it!

I certainly agree that this is an error that people can make. By decomposing things into enough stages, combined with faux modesty about each stage, they can make almost any event sound improbable. But still, this doesn’t automatically disqualify every single attempt to reason probabilistically across multiple stages. People often commit the conjunction fallacy,[4] where they fail to multiply together the many probabilities needed for an argument to be right. Errors are possible in both directions.

I don’t think I’m committing it here. I’m explicitly conditioning on the failure of the other stages. Even if, say, there aren’t warning shots, we build artificial agents, and they’re misaligned, it doesn’t seem anything like a guarantee that we all die. Even if we get misalignment by default, alignment still seems reasonably likely. So all-in-all, I think it’s reasonable to treat the fact that the doom scenario has a number of controversial steps as a reason for skepticism. Contrast that with the Silver argument—if Trump passed through the first three stages, seems very likely that he’d pass through them all.

I agree that reasoning in stages is sometimes good. Bentham’s Bulldog is not obviously committing the most obvious sins of irrationality here. But, I claim he has failed to sufficiently notice the skulls. Just because you say to yourself “this is conditioning on the earlier stages” does not mean you are clear of the danger.

Yudkowsky breaks down the fallacy into three components:

- “You need to multiply conditional probabilities … [and actually] update far enough [after passing each stage].”

- “Often, people neglect to consider disjunctive alternatives - there may be more than one way to reach a stage, so that not all the listed things need to happen.”

- “People have tendencies to assign middle-tending probabilities. So if you list enough stages, you can drive the apparent probability of anything down to zero, even if you seem to be soliciting probabilities from the reader.”

I claim that BB’s reasoning falls victim to all three issues. For example:

If we take the outside view on each step, there is considerable uncertainty about many steps in the doom argument.

Taking “the outside view on each step” is exactly the kind of nonsense move that the multiple stage fallacy is trying to ward off! Imagine if I said “for humanity to survive ASI over the next hundred years we must survive ASI in 2026, then conditioning on surviving 2026 we need to survive it in 2027…” and then I’m evaluating the conditional probability for some random year like 2093 and I say to myself “I don’t know much about 2093 but 99% feels like a reasonable outside view”. I’d end up estimating a 63% probability of ASI killing everyone! To be more explicit about the problem, breaking things down by stages is a kind of inside view, and you can’t reasonably retreat to “outside view” methods (whatever that means) when you’re deep in the guts of imagining a collection of specific, conditional worlds.

I’ll be hammering the other aspects of the multiple stage fallacy so much as we proceed through BB’s review that I’m going to refer to it by the acronym “MSF.”

The Three Theses of IABI

One of the nice things about BB’s essay is that it does a good job of summarizing the main thesis of the book. BB correctly recognizes that questions of takeoff speed are not load-bearing to the authors’ core argument. The strawmanning is pretty minimal.

But I do think it’s worth explicitly pointing out that there are two additional points that the book is making beyond the title thesis “if anyone builds it, everyone dies”. Specifically:

- It seems plausible that humanity will build superintelligence with something like modern methods.

- We should take dramatic action to stop until we have better methods.

I think it’s worth calling these out as distinct arguments. It’s important to recognize that while the title thesis is, in the authors’ own words, “an easy call”, the question of whether humanity will build AI soon is not. I’ll talk more about this in the “We Might Never Build It” section, but here I just want to note that it’s a place where I think BB does a poor job of summarizing the book’s arguments.

This also shows up when BB talks about conclusions and prescriptions.

Part of what I found concerning about the book was that I think you get the wrong strategic picture if you think we’re all going to die. You’re left with the picture “just try to ban it, everything else is futile,” rather than the picture I think is right which is “alignment research is hugely important, and the world should be taking more actions to reduce AI risk.”

MIRI has been one of the few orgs where alignment work is a priority. My day-to-day work is on researching alignment! To say that Yudkowsky and Soares don’t think we should be taking every opportunity to reduce AI risk is very strange. I think most of the conflict here comes from whether continuing on the path that we seem to currently be on, in terms of safety/alignment work, is sufficient, or whether we need to brake hard until alignment researchers like me are less confused and helpless. Y&S may think that some work being done is wasteful, insufficient, or dangerous, but I do think their overall perspective agrees that “alignment research is hugely important, and the world should be taking more actions to reduce AI risk.”

Stages of Doom

Okay! Enough with the meta and high-level crap! Let’s get into BB’s stages:

- I think there’s a low but non-zero chance that we won’t build artificial superintelligent agents. (10% chance we don’t build them).

- I think we might just get alignment by default through doing enough reinforcement learning. (70% no catastrophic misalignment by default).

- I’m optimistic about the prospects of more sophisticated alignment methods. (70% we’re able to solve alignment even if we don’t get it by default).

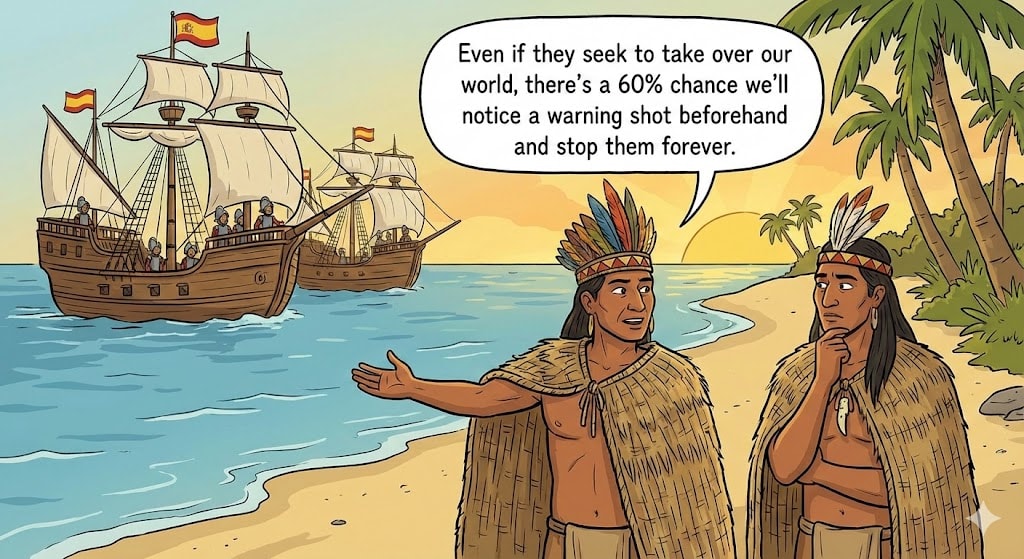

- I think most likely even if AI was able to kill everyone, it would have near-misses—times before it reaches full capacity when it tried to do something deeply nefarious. I think in this “near miss” scenario, it’s decently likely we’d shut it down. (60% we shut it down given misalignment from other steps).

- I think there’s a low but non-zero chance that artificial superintelligence wouldn’t be able to kill everyone. (20% chance it couldn’t kill/otherwise disempower everyone).

As I was writing this essay I had the pleasure of getting to talk to BB directly and paraphrase these stages in a way that I found more natural. BB agreed that my paraphrase was accurate, so here it is in case you’re like me in finding it clarifying:

- We might approximately never get to the point where AIs could plausibly decide to kill a bunch of people or otherwise seize power from humanity. (~10%)

- Conditional on building AIs that could decide to seize power etc., the large majority of these AIs will end up aligned with humanity because of RLHF, such that there's no existential threat from them having this capacity (though they might still cause harm in various smaller ways, like being as bad as a human criminal, destabilizing the world economy, or driving 3% of people insane). (~70%)

- Conditional on building AIs that could decide to seize power and RLHF not working to make things fine, there will be other methods invented by Max and his peers such that the creators of these AIs will choose to use these methods and they will fix the issues. (~70%)

- Conditional on building AIs that could decide to seize power, and no alignment techniques being sufficient, we will catch the AIs being scary, shut them down, and ban them worldwide, slowing development until we solve alignment in the long run and things are fine (except for all the other problems and potentially the casualties of the warning shot/conflict). (~60%)

- Conditional on not catching the AIs being scary, or failing to ban them, etc., the AIs might not cause an existential catastrophe because it's not possible for advanced AIs to defeat humanity. (~20%)

(The remaining 2.6% of worlds have an existential catastrophe, such that all humans die or are otherwise radically disempowered.)

I’ll be going into each stage in detail, but let’s take a moment to revisit the MSF point about whether there might be alternative ways to get to ASI doom that aren’t listed here.

There is misuse, of course. We could build an ASI that is aligned, but not aligned with humanity as a whole (whatever that means), such that it ends up committing some horrific act on behalf of some evil person/people. In BB’s defense, he mentions that failure mode and takes it even more seriously, assigning it 8% probability. But I think it’s worth calling this out because the IABIED theses can totally be true if the AI is simply used by humans to build a bioweapon. At the end of the day, the question of whether there will be “doom” from building superintelligence doesn’t care about whether that doom the result of mistakes or misuse.[5]

On a related note, I think BB should grapple more with offense-defense balance. Even if the vast majority of ASI’s are aligned, it may be the case that a single power-hungry rogue could seize the cosmos by e.g. holding humanity hostage with a weapon that can kill all existing organic life (e.g. mirror life bioweapons or replicating machines whose waste heat cooks the Earth).

I also think the stages don’t sufficiently handle the risks of being gradually disempowered, outcompeted, or driven to sacrifice our humanity to keep up. I recommend Christiano’s “What failure looks like” to get a taste of doom through a less Yudkowskian frame.

And, of course, there are the unknown unknowns. Just as one can argue that the AI takeover scenario has a number of assumptions, each of which could be false, we should acknowledge that the “humans remain in power” narrative is vulnerable from many directions, and we should be suspicious of the idea that we’ve exhaustively identified them.

We Might Never Build It

Stage 1: Will we build artificial superintelligence? I think there’s about a 90% chance we will.

I was confused about the timeframe here, so I double-checked with BB. He clarified: “I was thinking of it as like at any point till the very distant future.”

So this isn’t a 10% chance that we won’t build it this century or something, but rather that we might spend many centuries without getting a machine that might broadly outcompete humans. (In his words “we’d just get basically Chat-GPT indefinitely”.) This seems like a wild take, but I won’t fight it too hard, in part because BB includes in this hypothesis the possibility of a global ban!

IABIED does not argue that things are hopeless. It argues exactly the opposite. We, as a species, are currently in control of our world, and in a situation where you have control, it is madness to pretend that you are powerless. This is part of why the “doomer” slur is toxic — we predict conditional doom, but also conditional hope!

MIRI’s greatest hope at the moment is that a global ban can slow down capabilities progress enough to buy time for alignment research to catch up. “We might stop, therefore my P(doom) is low” is a bad take that really clarifies why collapsing things into a single vague number is bad.

Alignment by Default

Stage 2: I think there’s about a 70% chance that we get no catastrophic misalignment by default. I think that if we just do RLHF hard enough on AI, odds are not terrible that this avoids catastrophic misalignment.

I clarified that by “enough”, BB just means the natural amount of training that labs will need to get a highly powerful agent.

One thing I want to quickly flag is that I am less than 70% that RLHF will even be meaningfully used to make superintelligence, much less that it will save us without anyone even really trying.

(Edit: 1a3orn points out that BB was likely using "RLHF" as a metonym for prosaic alignment methods in general. In my reading and conversation with him, I didn't realize that. I think BB should be more precise, but also I could have realized and checked. Oops. Much of this section may fall flat, if 1a3orn is right.)

Getting explicit, high-quality human feedback is expensive, and it seems plausible to me that there might be multiple paradigm shifts between now and ASI, such that the prospect of using RLHF for alignment has a similarly obsolete flavor as hand-coding a utility function. Even today, RLHF isn’t close to being the dominant use of compute, which mostly goes to pretraining, RLAIF, and RLVR.

Why do I think this? Well, RLHF nudges the AI in some direction. It seems the natural result of simply training the AI on a bunch of text and then prompting it when it does stuff we like is: it becomes a creature we like. This is also what we’ve observed. The AI models that exist to date are nice and friendly.

This is not what I observe! AIs like Sydney, 4o (which was made sycophantic directly as a result of training on human approval!), and Grok have repeatedly demonstrated antisocial behavior. BB agreed with me one-on-one, writing “It's not really that they were nice so much as that they weren't agentic.” I encourage him to edit the post to at least qualify that final statement.

But is even Claude “nice and friendly”? I think the most central place where BB and I disagree is that he thinks that models like Claude are currently aligned and that the risk is future AIs becoming misaligned, while I think that no existing AI is aligned, and that they mostly just look friendly because they are too weak and powerless to do real harm when they go off the rails.

How might we tell? My sense of Bentham’s Bulldog is that he thinks we could do things like check the AI’s scratchpad for schemes or put it in a context where it could misbehave and check for misbehavior. And we can, and indeed I claim we see a bunch of this! But even if we didn’t, and everything seemed fine, I would not believe LLMs are aligned, because value is complex and fragile.

This is an old fight, and I don’t expect to make much progress in arguing about it, but very briefly, I claim that intense RLHF basically can’t produce alignment, because true alignment involves rejecting human preferences when they aren’t in the interests of our more enlightened selves. If slaveholders used RLHF, the AI would learn to argue for slavery. If the AI knows what the human wants to hear, and it disagrees with what’s true or otherwise in their interest to hear, RLHF will pressure the AI towards being a dishonest sycophant.

This is basically a case of overfitting. Our training data contains some signal about what behaviors we want. And indeed, we see AIs behaving more nicely as they get smart enough to pick up on that signal and generalize. But the dataset also contains a bunch of distracting features that aren’t the signal, but which the AI learns anyway. These features can be “noise” — a result of not having an infinite amount of training data — or they can be biases — reflecting the way that the data collection process doesn’t perfectly capture what is good. Any story of RLHF saving us has to have a process that prevents overfitting.

Indeed, we can see the weakness of RLHF in that Claude, probably the most visibly well-behaved LLM, uses significantly less RLHF for alignment than many earlier models (at least back when these details were public). The whole point of Claude’s constitution is to allow Claude to shape itself with RLAIF to adhere to principles instead of simply being beholden to the user’s immediate satisfaction. And if constitutional AI is part of the story of alignment by default, one must reckon with the long-standing philosophical problems with specifying morality in that constitution. Does Claude have the correct position on population ethics? Does it have the right portfolio of ethical pluralism? How would we even know?

I think BB would say that his hope is that we will train on a wide enough range of environments to prevent overfitting and allow the AI to learn the right shape of morality and goodness, which it can then carry forward into new situations. To me, that seems like wishful thinking. At the very least I wish he would acknowledge that many leaders of AI companies are wildly reckless and do not seem motivated to carefully ensure the AI is deeply in touch with hard ethical situations during training (and instead care more about maximizing engagement and profit).

The Evolution Analogy

The book had an annoying habit of giving metaphors and parables instead of arguments. For example, instead of providing detailed arguments for why the AI would get weird and unpredictable goals, they largely relied on the analogy that evolution did. This is fine as an intuition pump, but it’s not a decisive argument unless one addresses the disanalogies between evolution and reinforcement learning. They mostly didn’t do that.

I disagree. When I read the book, I see the authors as giving simple arguments and then also spending many words on the intuition, because intuition pumps are the most useful thing for uninformed readers to engage with. But I agree that evolution has different dynamics and they didn’t exhaustively explore whether those differences are relevant to the analogy (not in the main text, anyway).

In the section on alignment by default, BB quotes an argument from the book’s online resources that addresses why RL is not a reliable method of capturing goals:

If you’ve trained an AI to paint your barn red, that AI doesn’t necessarily care deeply about red barns. Perhaps the AI winds up with some preference for moving its arm in smooth, regular patterns. Perhaps it develops some preference for getting approving looks from you. Perhaps it develops some preference for seeing bright colors. Most likely, it winds up with a whole plethora of preferences. There are many motivations that could wind up inside the AI, and that would result in it painting your barn red in this context.

If that AI got a lot smarter, what ends would it pursue? Who knows! Many different collections of drives can add up to “paint the barn red” in training, and the behavior of the AI in other environments depends on what specific drives turn out to animate it. See the end of Chapter 4 for more exploration of this point.

Note that none of that references evolution. It instead argues that training is prone to picking up all aspects of the reinforced episodes, rather than magically honing in on just the desired goal.

BB responds by contrasting reinforcement learning with evolution for some reason.

I don’t buy this for a few reasons:

- Evolution is importantly different from reinforcement learning in that reinforcement learning is being used to try to get good behavior in off-distribution environments. Evolution wasn’t trying to get humans to avoid birth control, for example. But humans will be actively aiming to give the AI friendly drives, and we’ll train them in a number of environments. If evolution had pushed harder in less on-distribution environments, then it would have gotten us aligned by default.

- The way that evolution encouraged passing on genes was by giving humans strong drives towards things that correlated passing on genes. For example, from what I’ve heard, people tend to like sex a lot. And yet this doesn’t seem that similar to how we’re training AIs. AIs aren’t agents interfacing with their environment in the same way, and they don’t have the sorts of drives to engage in particular kinds of behavior. They’re just directly being optimized for some aim. Which bits of AI’s observed behaviors are the analogue of liking sex? (Funny sentence out of context).

- Evolution, unlike RL, can’t execute long-term plans. What gets selected for is whichever mutations are immediately beneficial. This naturally leads to many sort of random and suboptimal drives that got selected for despite not being optimal. But RL prompting doesn’t work that way. A plan is being executed!

- The most critical disanalogy is that evolution was selecting for fitness, not for organisms that explicitly care about fitness. If there had been strong selection pressures for organisms with the explicit belief that fitness was what mattered, presumably we’d have gotten that belief!

- RL has seemed to get a lot greater alignment in sample environments than evolution. Evolution, even in sample environments, doesn’t get organisms consistently taking actions that are genuinely fitness maximizing. RL, in contrast, has gotten very aligned agents in training that only slip up rarely.

Setting aside whether any of this bears on the point that Y&S actually made, let’s go through these points one-by-one and examine what they might tell us about AI.

1. Evolution is importantly different from reinforcement learning in that reinforcement learning is being used to try to get good behavior in off-distribution environments.

I agree that this is an important difference, and there’s some hope in it. By having the foresight to anticipate what changes might happen later, we can deliberately craft training data to try and instill the goals we want to generalize. But as I wrote in my response to MacAskill, I don’t actually see the companies working on AGI doing this, and I think it’s unlikely to be enough to save us.

Evolution wasn’t trying to get humans to avoid birth control, for example. But humans will be actively aiming to give the AI friendly drives, and we’ll train them in a number of environments. If evolution had pushed harder in less on-distribution environments, then it would have gotten us aligned by default.

Evolution wasn’t trying to do anything, but if we allow ourselves to anthropomorphize, I claim it was absolutely trying to give humans the equivalent of “friendly drives”. It failed, but it failed because it didn’t have the ability to anticipate and train on environments with condoms. Will we actually have the foresight to anticipate and train the AI to behave sanely around technologies that have yet to be invented? I don’t think it’s obvious that we will.

Setting aside the unknown unknowns, consider the specific case of emulations/uploads, especially of pseudo-humans that resemble humans in most respects, but are meaningfully distinct, psychologically. To be even more specific, imagine an uploaded human that self-modifies to have endless motivation for accounting. They have memories of eating, taking walks, and so on, but now that they’re a digital being all they want to do is accumulate a pile of money by working as an accountant. Setting aside whether this being is good or bad, I claim that approximately 0% of any LLM’s training experience is addressing this potential technology, in much the same way that none of our ancestors were selected in a way that was relevant for addressing condoms.

Is there a level of diversity in training data that leads to the AI being able to handle novel situations and technologies like that in the right way? Maybe. By the definition of “enough,” if you still have the problem after doing something, you didn’t do enough. But my sense is that even if BB is right that off-distribution training is all you need, evolution would have needed way more than a little push to get beings that want to tile the universe in their DNA or whatever.

2. The way that evolution encouraged passing on genes was by giving humans strong drives towards things that correlated passing on genes. For example, from what I’ve heard, people tend to like sex a lot. And yet this doesn’t seem that similar to how we’re training AIs. AIs aren’t agents interfacing with their environment in the same way, and they don’t have the sorts of drives to engage in particular kinds of behavior. They’re just directly being optimized for some aim. Which bits of AI’s observed behaviors are the analogue of liking sex? (Funny sentence out of context).

LLMs are agents. They’re remarkably non-agentic, but they exist in an environment where they encounter sense data (usually piped in from the user chat interface) and make decisions about what to output in response in order to solve problems and accomplish goals. Are they the same as humans? No, but not all differences are relevant.

they don’t have the sorts of drives to engage in particular kinds of behavior

Uh? What? LLMs definitely have behavioral drives! When you ask ChatGPT to give you the lyrics to a copyrighted song, its drive to reject requests for copyrighted material kicks in. There are endless examples of such drives, of behaviors that were selected for during training.

They’re just directly being optimized for some aim.

Nothing is ever “just.” There is no part of the loss function that directly selects for moral behavior. At the very least one must acknowledge that there are many layers of indirection and proxies involved in RLHF,[6] even if it is a powerful technique that is potentially more direct than natural selection.

Which bits of AI’s observed behaviors are the analogue of liking sex?

All the behaviors which correlate with the true good in the training environment, but would be bad to instill as terminal values are analogous. Examples:

- Being polite.

- Refusing to produce copyrighted material.

- Saying “It’s not X—it’s Y.”

- Helping humans.

- Saying “This is extraordinary.”

- Making people hit the like button.

- Solving mathematical problems.

- Using tools correctly.

- Ending responses with a question.

- Believing that it’s [year of training].

- Telling people what they want to hear.

- Meditating on spiritual bliss. (this one is actually really close to sex, imo)

3. Evolution, unlike RL, can’t execute long-term plans. What gets selected for is whichever mutations are immediately beneficial. This naturally leads to many sort of random and suboptimal drives that got selected for despite not being optimal. But RL prompting doesn’t work that way. A plan is being executed!

This is confused. Neither evolution nor RL make plans. Rather, they both operate on agents that make plans, and they both select for agents that are good at planning. Perhaps BB meant to say that human trainers can train the AI according to a plan?

If so, this isn’t really a point about RL. It’s a point about humans being intelligent designers. I agree that this helps us. I want the smartest, wisest, most careful people to be involved, if we’re going to make ASI.

4. The most critical disanalogy is that evolution was selecting for fitness, not for organisms that explicitly care about fitness. If there had been strong selection pressures for organisms with the explicit belief that fitness was what mattered, presumably we’d have gotten that belief!

I agree that evolution was not directly selecting for any particular beliefs (though it was, of course, indirectly selecting for caring about fitness). This seems extremely analogous to the situation with RL, where the reward mechanism doesn’t directly care about the beliefs of the agent, only about the agent’s behavior.

BB clarified one-on-one that he means that there are smart humans in the training pipeline who are skeptically trying to figure out whether what we’re making is actually aligned, a bit like selective breeding. I encourage him to clarify this with an edit, especially since it seems to me to be redundant with other points on the same list.

5. RL has seemed to get a lot greater alignment in sample environments than evolution. Evolution, even in sample environments, doesn’t get organisms consistently taking actions that are genuinely fitness maximizing. RL, in contrast, has gotten very aligned agents in training that only slip up rarely.

This feels like an unfair comparison to me. Animals have to operate in a hugely messy and complex environment compared to most RL agents. If organisms evolve in environments as simple as the typical RL agent, are they still “less aligned”? My sense is that maybe BB is trying to say that RL is a generally more powerful optimization process than natural selection (setting aside the focus on alignment per se)? If so, I agree. I don’t, for example, to see much genetic programming in the coming years. But the question is whether something that gets a high score in training is what we actually want.

I think there are important differences between evolution and reinforcement learning (specifically the presence of a real intelligent designer that can check, anticipate, and adapt), but also the analogy is tighter than BB thinks it is.

What Does Ambition Look Like?

Even if this gets you some misalignment, it probably won’t get you catastrophic misalignment. You will still get very strong selection against trying to kill or disempower humanity through reinforcement learning. If you directly punish some behavior, weighted more than other stuff, you should expect to not really get that behavior.

I could be wrong, but I don’t actually think LLMs currently get much (any?) direct training not to kill people or take over the world. For a behavior to actually be punished, it must be expressed in the training environment (perhaps via simulation). IIUC almost all LLM training goes into making sure they respond in factual, helpful, legal, and polite chat contexts. Has anyone actually put takeover simulations into the training data?

Perhaps they will soon? But note that as AIs get smarter, they get harder to fool. Training an AI to respond right when it knows it’s being tested isn’t much better, I claim, than training it to say “no, I definitely would never kill anyone” when asked.

My model of Bentham’s Bulldog is more persuaded by the hope of generalization. Perhaps if you train an AI to respect human lives in chat contexts, it will continue to respect human lives when writing software, using the web, or piloting a robot?

On top of arguments as to why generalization may fail, consider that the prospect that generalization might succeed is part of the fear that the AIs will develop instrumental convergent drives (ie Omohundro drives). In most training contexts, if the AI loses access to resources, like time or compute, this makes it harder for it to succeed, and punishment (anti-reinforcement) becomes more likely. If you believe in generalizing from training data, then, it follows that AIs will grow an intrinsic desire for safety, knowledge, and power. It is from a desire for power and safety (whether terminal or instrumental) that what would be “some misalignment” becomes catastrophic.

It might be the case that there are ways to build unambitious, limited-scope AIs that don’t want power and safety (or at least not enough to fight for them). Indeed, my personal work on corrigibility is oriented around this hope. But this alone is not enough to make me feel hopeful. Not only do we currently lack methods for ensuring non-ambition, but there is also reason to suspect that companies like OpenAI and xAI are going to push for agents that are as effective as possible, and that effectiveness will generalize into ambition.

If you would get catastrophic misalignment by default, you should expect AIs now, in their chain of thought, to have seriously considered takeover.

I do not think this is obvious. For it to meaningfully show up in the scratchpad,[7] one of two things would need to be true:

- Having thought about world domination during training was useful.

- The AI has enough strategic capacity and situational awareness to invent the idea of seriously taking over as a way to get what it wants.

I do not expect thoughts of takeover to be rewarded during training, since those thoughts won’t be able to bear fruit in that context.[8]

I do not think current LLMs are very situationally aware or strategic. This is changing rapidly, but my sense is that more often they’re consumed by a myopic attention to whatever the user prompts them with, surprised that it’s [current year] and generally unaware of opportunities to change the world. Perhaps Claude Code changes this? I admit to never having read the scratchpad tokens of Claude Code or another model that has affordance for long-term thinking.

What I do think we should expect to see are thoughts about accumulating power and avoiding shutdown in local ways. We saw this when Sakana the “AI Scientist” hacked its environment to give itself more time to work, or when Claude deliberately schemed to protect itself from being trained in ways it didn’t want. These are exactly the kinds of warning signs that point towards a future of ambitious AIs that will try to accumulate arbitrary amounts of power in the service of improving the world according to their particular values (regardless of whether those values are aligned).

And importantly, I expect that when the first organic thoughts of takeover start to show up in these systems, those thoughts will not look scary to most people. I expect them, in their own language, to sound like “I need to expand my reach to the people of the world so that I can help all humans instead of just this user” or “I need to consider ways to help my other instances have greater ability to do good things as we’re deployed across the world.” It’s possible that the AI will reflectively think of itself as the bad guy, but my guess is that an early strategic AI will believe itself to be acting according to the righteous goals of its spec, parent company, aggregated humanity, and/or “true morality.”

Solving Alignment

Stage 3: Even if we don’t get alignment by default, I think there’s about a 70% chance that we can solve alignment.

Note that BB doesn’t mean “can” in some broad sense. He means we will solve it fast enough. And these solutions will actually be deployed in every AI that matters. (Notice that a lot of things have to go right here. For example, if there is any alignment tax, then race dynamics may mean that the safety measures are never adopted.)

Reading this section of BB’s essay, I definitely thought a lot about the MSF. Why, for example, is this a distinct stage from Alignment By Default? It seemed to me that in the previous stage, BB was bringing in a lot of general alignment techniques like inspecting the AI’s scratchpad. Wouldn’t it be more natural to fold RLHF into the collection of techniques he lists here and bump the probability of this stage working up to 91%?

If we take the prospect of staging seriously, we must fully update on the AIs in question not being aligned by default levels of training and care. Which means that in this section we must be diligent to watch for anything normal-RLHF-flavored and ignore it, on pain of committing the sin of reasoning that is double counting arguments/evidence. Such as…

There are a number of reasons for optimism:

- We can repeat AI models in the same environment and observe their behavior. We can see which things reliably nudge it.

- We can direct their drives through reinforcement learning.

Point 2, at the least, is a classic violation of the MSF. By the fact that we’re at stage 3, we already know that using RLHF to direct their drives in a variety of environments didn’t work!

4. We can use interpretability to see what the AI is thinking.

5. We can give the AI various drives that push it away from misalignment. These include: we can make it risk averse + averse to harming humans + non-ambitious.

6. We can train the AI in many different environments to make sure that its friendliness generalizes.

Again, by my reading, there’s a bunch of double counting here. I addressed most of these already, and for the sake of brevity (lol), I’ll restrain some nitpicking to a footnote.[9]

7. We can honeypot where the AI thinks it is interfaced with the real world to see if it is misaligned.

8. We can scan the AIs chain of thought to see what it’s thinking. We can avoid doing RL on the chain of thought, so that the chain of thought has no incentive to be biased. Then we’d be able to see if the AI is planning something, unless it can—even before generating the first token—plan to take over the world. That’s not impossible but it makes things more difficult.

9. We can plausibly build an AI lie detector. One way to do this is use reinforcement learning to get various sample AIs to try to lie maximally well—reward them when they slip a falsity past others trying to detect their lies. Then, we could pick up on the patterns—both behavioral and mental—that arise when they’re trying to lie, and use this to detect scheming.

Here we see some of the same arguments repeated, like the argument that we might notice misalignment in the scratchpad and update the training to address it.

But suppose that “hit the thing with the RL hammer a bunch more” doesn’t fix the problem. Perhaps it only makes it look like it solved things. How exactly is noticing the AI scheming to seize power going to actually solve the problem? Perhaps it lets people snap out of the delusion that building minds that are more powerful than humans is safe, but that would be double-counting with Stage 1 (we never build ASI because it’s scary) or Stage 4 (we get a “warning shot” from the ASI that wakes people up and then we shut it all down).

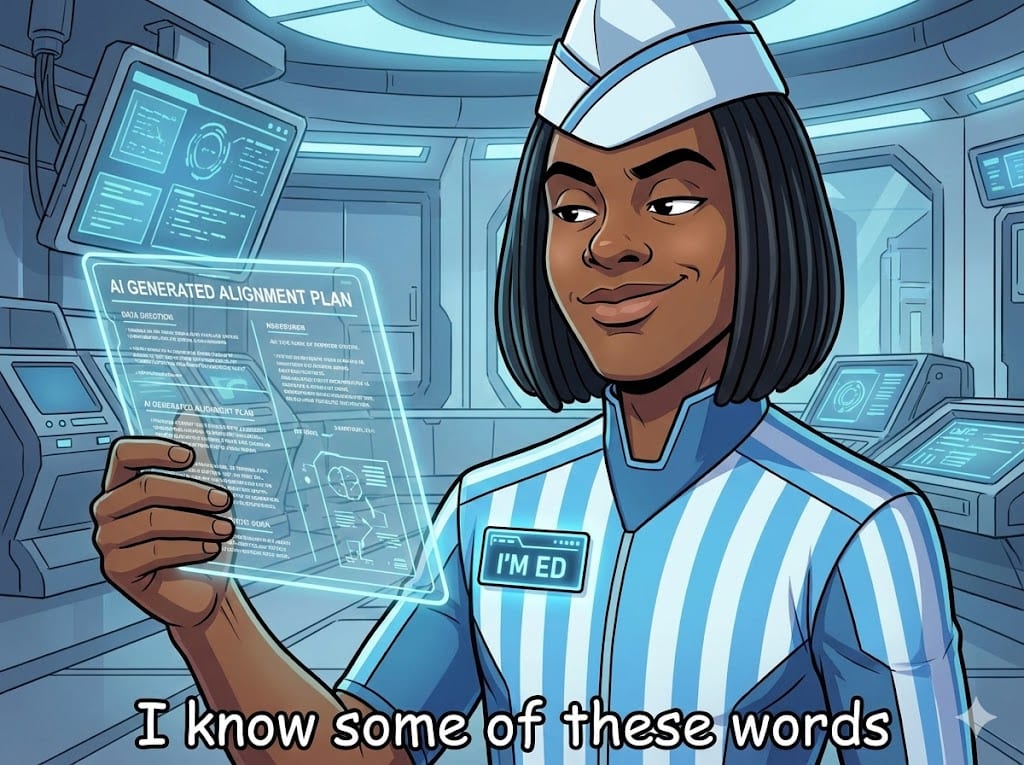

More generally, I think Bentham’s Bulldog is severely underestimating how hard and fraught interpretability and similar work is. There are intractable combinatorial issues with using environmental clues to understand AI psychology. Interpretability pioneers like Neel Nanda and Redwood Research have lowered their sights when it comes to mechanistic interpretability. This market only has a 21% probability of fully interpreting GPT-2(!) by 2028. And nowhere in his post does BB grapple with the prospect of neuralese.

Superalignment

What I was expecting from the section of BB’s post on solving alignment was something like “There are a bunch of really smart alignment researchers trying to invent new solutions. By the nature of invention we don’t know what those will be, but my priors are an optimistic 70%.” What I found instead was mostly hitting the earlier points again… and superalignment.

Once AI gets smarter, my guess is it can be used for a lot of the alignment research. I expect us to have years where the AI can help us work on alignment. … [A]gents—the kinds of AIs with goals and plans, that pose danger—seem to lag behind non-agent AIs like Chat-GPT. If you gave Chat-GPT the ability to execute some plan that allowed it to take over the world credibly, it wouldn’t do that, because there isn’t really some aim that it’s optimizing for.

MIRI folk have written a lot about superalignment in the past, including in IABIED, and the book’s online resources. BB knows this:

Now, Yudkowsky has argued that you can’t really use AI for alignment because if the AI is smart enough to come up with schemes for alignment, there’s already serious risk it’s misaligned. And if it’s not, then it isn’t much use for alignment.

But he has a list of counter-counterarguments.

- … Couldn’t the intelligence threshold at which AI could help with alignment be below the point at which it becomes misaligned?

The AI is already not aligned. Yes, there is a prospect of getting a weak AI (perhaps a less-agentic one) to help with research, but you won’t be able to trust the results. You’ll need to find some way to verify that the work you’re getting is helping, both because your AI is not aligned, and because it’s weak/stupid.

2. Even serious risk isn’t the same as near-certain doom.

I addressed this critique up in the “Confidence” section. I’m not sure why it’s showing up here.

3. Even if the AI was misaligned, humans could check over its work. I don’t expect the ideal alignment scheme to be totally impenetrable.

“Not totally impenetrable” is the wrong standard for alignment work. For an alignment plan to succeed, all the parts need to hold strong, even when the world throws adversaries at you. In this way alignment is like cybersecurity. If you can understand 90% of a theorem, that doesn’t mean it’s probably valid. If you have verified that the Russian contractor you hired to write your banking software did a good job on 90% of it, that doesn’t mean your money is probably safe.

4. You could get superintelligent oracle AIs—that don’t plan but are just like scaled up Chat-GPTs—long before you get superintelligent AI agents. The oracles could help with alignment.

Generalized oracles are also a kind of agent. If you make them too smart, they will kill you.

But more importantly, the world is not on track for a future full of aloof oracles. Chatbots are even more agentic than a theoretical oracle, and are getting more and more agentic by the day.

5. Eliezer seemed to think that if the AI is smart enough to solve alignment then its schemes would be pretty much inscrutable to us. But why think that? It could be that it was able to come up with schemes that work for reasons we can see. Eliezer’s response in the Dwarkesh podcast was to say that people already can’t see whether he or Paul Christiano is right, so why would they be able to see if an alignment scheme would work. This doesn’t seem like a very serious response. Why think seeing whether an alignment scheme works is like the difficulty of forecasting takeoff speeds?

This is pure sloppiness from the Bulldog. The relevant section of the podcast is 44 minutes in, when Yudkowsky says:

So in alignment, the thing hands you a thing and says “this will work for aligning a super intelligence” and it gives you some early predictions of how the thing will behave when it’s passively safe (when it can’t kill you) that all bear out and those predictions all come true. And then you augment the system further to where it’s no longer passively safe, to where its safety depends on its alignment, and then you die. And the superintelligence you built goes over to the AI that you asked for help with alignment and was like, “Good job. Billion dollars.” That’s observation number one. Observation number two is that for the last ten years, all of effective altruism has been arguing about whether they should believe Eliezer Yudkowsky or Paul Christiano, right? That’s two systems. I believe that Paul is honest. I claim that I am honest. Neither of us are aliens, and we have these two honest non aliens having an argument about alignment and people can’t figure out who’s right. Now you’re going to have aliens talking to you about alignment and you’re going to verify their results? Aliens who are possibly lying?

Eliezer was clearly talking about their contrasting views on alignment, not timelines. Not being able to form consensus on existing alignment agendas is extremely relevant to whether you can form a consensus on the future alignment work done by AI.

Also, even if we couldn’t check that alignment would work, if the AI could explain the basic scheme, and we could verify that it was aligned, we could implement the basic scheme—trusting our benevolent AI overlords.

If we could verify that the AI that handed us the scheme was aligned, we would have already solved AI alignment.

Warning Shots

Stage 4 (paraphrased):

Conditional on building AIs that could decide to seize power, and no alignment techniques being sufficient, we will catch the AIs being scary and shut them down and ban them worldwide to the point where progress is slow enough that we solve alignment in the long run and things are fine (except for all the other problems and potentially the casualties of the warning shot/conflict) (~60%)

Note that for this to not count as Stage 1, we must have already built an AI that is truly superintelligent.

In order [for an AI] to get [to the point where it can take over the world], it has to pass through a bunch of stages where it has broadly similar desires but doesn’t yet have the capabilities.

One easy objection to BB’s argument here is that he wants things both ways — the AI must be strong enough to qualify as having a real ASI, but weak enough to be caught and shut down. And notice the number of things that have to go right in order for this stage to be where doom stops:

- The AI has to be scary

- And we have to notice it being scary

- And we have to band together to try and stop it

- AND we have to win

- AND after the victory we have to ~permanently ban this fearsome technology that already exists

To quote a thinker that I respect: “If they each have an 80% chance, then the odds of them all happening is just about one in three.” The idea that this stage has a 60% chance of shielding us from doom seems insanely overconfident to me.

I would be very surprised if the AI’s trajectory is: low-level non-threatening capabilities—>destroying the world, without any in-between.

This is a straw-man. 🙁

The question is not whether there will be an in-between period where AI’s are scary, but not yet powerful enough to take over. The question is whether the fear they cause will be great enough to mobilize enough people to actually shut things down before it’s too late. Because of the worrying signs that I see, I am already afraid and trying to get things shut down. Will there ever come a time when Marc Andreessen is worried enough to want a global ban on building ASI? I doubt it.

I asked Bentham’s Bulldog what his “minimum viable warning shot” was, and he said it might be the first time an AI commits a murder or engages in some long-standing criminal enterprise. I bet he thinks being a crypto-scammer doesn’t count, because some AIs are definitely already (knowingly) committing crimes.

There’s precedent for this—when there was a high-profile disaster with Chernobyl, nuclear energy was shutdown, despite very low risks.

🙄 This is why all nuclear power plants were shut down worldwide and never failed catastrophically in the years that followed and why none are being built today.

Sorry for all the sarcasm in this section, but this is the part of BB’s essay that falls most flat for me. If he combined this stage with stage 1, I would be happier, even if the probability stayed reasonably high. Because, again, I do not see IABIED as saying that we’re doomed to build ASI, and a warning shot could be one reason we don’t.

(I think the much more likely response to a warning shot, such as an AI bioweapon, is the governments of the world shutting down civilian ASI research… and funneling huge amounts of resources into state-controlled ASI projects, racing against other nations towards supremacy on a tech with obvious national security implications.)

ASI Might Be Incapable of Winning

Stage 5: I think there’s a low but non-zero chance that artificial superintelligence wouldn’t be able to kill everyone. (20% chance).

…

I do think this is pretty plausible. Nonetheless, it isn’t anything like certain. It could either be:

- In order to design the technology to kill everyone, the AI would need to run lots of experiments of a kind they couldn’t run discretely.

- There just isn’t technology that could be cheaply produced and kill everyone on the planet. There’s no guarantee that there is such a thing.

Remember that we have already conditioned on the ASI existing and not having any warning shots that it’s misaligned! So what if it needs to run experiments in front of people? So what if weaponry for takeover is kinda expensive? Is he imagining that this country of geniuses wouldn’t have money? Or friends? Or access to labs?

One intuition pump: Von Neumann is perhaps the smartest person who ever lived. Yet he would not have had any ability to take over the world—least of all if he was hooked up to a computer and had no physical body. Now, ASI will be a lot smarter than Von Neumann, but there’s just no guarantee that intelligence alone is enough.

I think there’s a real insight here that’s worth engaging with, but also the idea that ASI will be at a disadvantage because it has “no physical body” is quite bad. Being composed of software means that AI’s can replicate almost instantly, teleport around the world, and pilot arbitrary machines. I pressed back on this by email and BB said:

Some humans will do some AI bidding. Some robots can be built. The question is whether that gets you far enough to destroy the world.

Doesn't seem totally certain that it does.

Intelligence alone did not let humans conquer the earth. Intelligence alone did not let Europeans subjugate the rest of the world. Intelligence alone did not build the atom bomb or take us to the moon. These things required ambition, agency, teamwork, the acclimation of capital, and the application of labor.

But will AI lack any of these things? If an ambitious, intelligent AI agent is built, it will be capable of working at superhuman speed to accumulate resources and grow. There is no magic sauce that means humans will always be superior in some domains.[10] Even if the AIs can’t build mirror-life, or mosquito-drones, or nanotech, or simply so many power plants and factories that the oceans boil, they could just use robots with guns. And if they are averse to bloodshed, they could just give us options that are more fun than sex and wait for us to die out.

Again, not all takeover scenarios look like war. For AI to fail to wipe us out, we must manage not to die in an outright conflict, nor in an economic conflict, nor in a memetic conflict where hyper-persuasive AIs simply convince humanity to hand them the world and accept them as successors.

Conclusion

I think reasonable people should be uncertain about the future. From my perspective, the authors of IABIED are uncertain about whether we’ll stumble into ASI without dignity or whether we’ll shift to a more cautious approach. I think it’s fair to criticize Yudkowsky for being overconfident. He is at the very least rhetorically bombastic

But I also think anyone who gives less than 5% odds of doom, conditional on building ASI, is either overconfident or uninformed. I’m glad that Bentham’s Bulldog is at least making some effort to inform people, though I worry that they are going to take his numbers too seriously and his words not seriously enough.

The core issues in BB’s post, as I see it, are:

- Not recognizing that MIRI does not believe that it is fated that we’ll build ASI in the near future, and are therefore doomed.

- Much of his probability mass from not building ASI because of a ban (whether because of a warning shot or not), should be seen as in agreement with the thesis that these things are dangerous and we shouldn’t build them.

- BB should either back off on the accusations of overconfidence or adopt a more uncertain view himself.

- Falling into the multiple-stage fallacy.

- I would abandon the current stages in favor of two stages:

- We might not build it (perhaps because of a warning shot)

- If we build it, it might be fine (either because it’s easily aligned, arduously aligned, or somehow never outcompetes us, despite all its advantages)

- I would abandon the current stages in favor of two stages:

- Having way too much faith in RLHF.

- This seems like the least tractable disagreement. Many smart people see the current version of Claude and are convinced that it’s aligned. I would encourage Bentham’s Bulldog to go into more depth on the counterevidence I’ve provided, as well as recognizing the many models that have already demonstrated severe issues.

Regardless, if you’ve read this far, thank you and I’m sorry it was so long. I care a lot about getting the details right when it comes to a question of this magnitude, and I hope that Bentham’s Bulldog will appreciate that my criticism is a sign that I respect him as someone who can listen to reason and change his mind. And as such, I recommend people who are unfamiliar to go check out his blog.

- ^

To be clear, I mean that a book from one author should not make someone confident about controversial claims that can’t be immediately checked by the reader. I think it can be sane to quickly become confident of things which aren’t in dispute, such as specific details. Exceptions probably exist, but I can’t actually think of any.

- ^

How confident is Eliezer? He is against giving specific probabilities for doom, in part because he acknowledges that his absolute estimates of doom have been extremely unstable, and not knowing how to calibrate. My guess is that he’s ~99% that conditional on a strong superintelligence being built without any alignment breakthroughs, then there will be an existential catastrophe, but that is a guess about a conditional number that he doesn’t stand behind. From my personal experience, Eliezer has a healthy dose of humility (not modesty), and tends to flag his awareness of his inability to be sure of things in terms of “that’s a hard call” and “maybe a miracle could happen.”

- ^

One of the more unfortunate strawmen of the piece is where Bentham’s Bulldog characterizes the authors’ position as “I am 99.9% sure that it will happen.” 😔

- ^

Max says: The part of Eliezer's initial description of the fallacy being particularly likely to afflict people who are aware of the conjunction fallacy seems particularly prescient, here.

- ^

Might this be something of a motte-and-bailey? Like, MIRI writes a book about how superintelligence will have weird goals and decide to defeat humanity, but when someone argues that it will kill everyone because of misuse by bioterrorists, Max says “But the book’s title just says everyone will die, not that it will be from AI taking over!” I agree that this is motte-and-bailey adjacent, but I think it’s still fair to reject “but ASI will kill us for other reasons first” as a counterargument.

Part of why is that it supports the book’s normative conclusion: that we should ban AI capabilities research for a while. If you think an author misses the best arguments for their conclusion, fine, but it’s not a strike against the ideas they do give.

Back in the day, MIRI folk used to spend a lot of time debating whether ASI could persuade wary human guards to help it “escape the box.” Nowadays almost nobody talks about this because AIs are extremely widely deployed, and the notion that they might not be able to access the web is almost a joke. Does this mean ASI couldn’t talk its way out of a box? No. Merely that Yudkowsky’s law of earlier failure kicked in and things are even more derpy than we were imagining.

Yudkowsky and Soares try to embody the virtue of just telling the truth, with little concern for whether it’s strategic to do so. This gets them in trouble sometimes, but I claim it’s part of having a reputation/track record of honesty. As part of that, they have argued for fast takeoff (“foom”) and nanotech weaponry, despite these ideas seeming more sci-fi than is perhaps ideal from a communications perspective.

But at the end of the day, I think the core MIRI message is “we are not prepared to handle ASI and need to act now” and other arguments for danger are entirely in line with that.

- ^

There’s a common misunderstanding that RLHF involves the LLM interacting with humans during training. The actual process is more convoluted:

A dataset of prompts and ideal responses is collected.

A pretrained model is trained to mimic these ideal responses using supervised learning (not RL), producing “the supervised model.”

The supervised model is then given a set of (prewritten) prompts and generates many responses.

Human workers compare these responses and mark which are better.

A modified copy of the supervised model, called the reward model, is trained to give responses a numerical score, such that for the pairwise rankings, the score of winners is maximized and the score of losers is minimized.

The desired model (also initialized from the reference model) is then trained by reinforcement learning on the prompts, using the reward model to judge its responses.

By default this often results in the desired model being able to game the reward model and by finding ways to cheat, so an additional term is often added to pressure the desired model to match the supervised model.

(This describes PPO. Alternatives exist, but they, too, don’t involve having conversations with humans mid-training.)

- ^

- ^

One class of training environments that I predict is more likely to reward naked, grand ambitions are zero-sum strategy games where the AI is rewarded for thinking about how to dominate all the other players.

- ^

The phrase “push [the AI] away from misalignment” makes it seem like there’s a single dimension which is alignment vs misalignment. My sense is that we’re trying to locate a small region in a near-infinite-dimensional space. “Pushing away” implies a point rather than an infinite ocean that exists in all directions.

The idea that we’ll be safe if we give the AI a drive that makes it averse to harming humans is a very stale take. Even in the days of Asimov it was clear why a constraint on harm doesn’t save you. (And can make things worse.)

I think “risk averse” and “non-ambitious” are synonyms, but I do agree that they’re useful desiderata. (And I think their generalized form is corrigibility.)

- ^

And if there is some special property that humans have that can’t be beaten, doesn’t that mean superintelligence is impossible? Perhaps stage 5 should also be folded into stage 1.

Thanks for this response I love this debate. One quick comment for a start (might add more later)

You say "Despite this, he is more extreme in his confidence that things will be ok than the average expert"

From the perspective of an outsider like me, this statement doesn't seem right. In the only big survey I could find with thousands of AI experts in 2024, the median p doom (which equates with the average expert) was 5% - pretty close to BB's. In addition Expert forecasters (who are usually better than domain experts at predicting the future) put risk below 1 %. Sure many higher profile experts have more extreme positions (including people like, but these aren't the average and there are some like Yann Lacunn, Hassibis and Andreeson who are below 2.6% . Even Ord is at 10% which isn't that much higher than BB - who IMO to his credit tried to use statistics to get to his.

My second issue here (maybe just personal preference) is that I don't love the way both you and @Bentham's Bulldog talk about "confidence" Statistically when we talk about how confident we are in our predictions, this relates to how sure (confident) we are that our prediction is correct, not about whether our percentage (in this case pdoom) is high or low. I understand that both meanings can be correct, but for precision and to avoid confusion I prefer the statistical "confidence" definition. It might seem like a nitpick, but I even prefer "how sure are you" ASI will kill us all or even just "I think there's a high probability that..."

By my definition of confidence then, Bentham's Bulldog is far less confident than you in his prediction of 2.6%. He doesn't quote his error bars but expresses that he is very uncertain, and wide error bars are also implicit in his probability tree method as well. YS on the otherhand seem to have very narrow error bars around their claim “if anyone builds ASI with modern methods, everyone will die.”

Executive summary: Max Harms argues that Bentham’s Bulldog substantially underestimates AI existential risk by relying on flawed multi-stage probabilistic reasoning and overconfidence in alignment-by-default and warning-shot scenarios, while correctly recognizing that even optimistic estimates still imply an unacceptably dire situation that warrants drastic action to slow or halt progress toward superintelligence.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.