Highlights

- Comparing top forecasters and domain experts finds that past studies mainly were not comparing apples to apples and that the assertion that superforecasters were 30% better than intelligence analysts was unjustified.

- Samotsvety's Nuclear Forecasts got picked up in the Spanish press and criticized by a pessimistic nuclear expert.

- Forecasting Wiki launched

- Polymarket is inflating its volume by incentivizing wash trading. (edit: apparently not the case, will issue a correction in the next issue)

Index

- The state of forecasting

- Notable news

- Platform by platform

- Relevant research

You can sign up for this newsletter on substack, or browse past newsletters here.

The state of forecasting

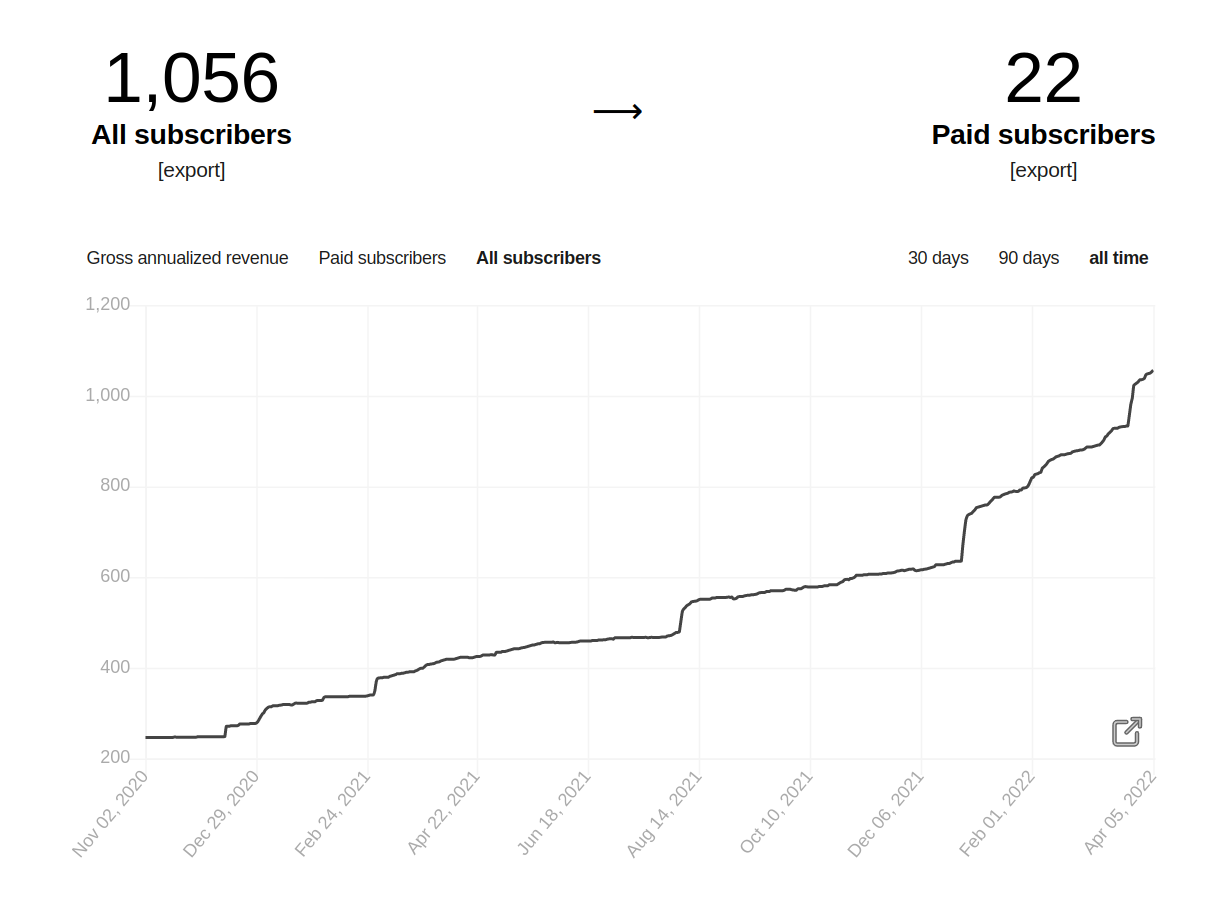

On account of getting a plug on one of Spain's most-read newspapers, this newsletter has reached 1,000 subscribers:

So I thought I would summarize the state of forecasting as I see it, striving to be informative to new readers. If you're already familiar with the key points, you might want to skip to the next section.

The main problem is bullshit or lack of epistemic virtue and ability. The US misled itself into thinking that Iraq still had weapons of mass destruction or that everything would be okay in Afghanistan (a). People were not expecting covid to last so long. And everyone keeps expecting a better brand of politician to show up.

What is the alternative? The alternative is to develop better models of the world and then use those better models to make better decisions.

But how do we know which models of the world are good? How do we differentiate real understanding from fake understanding? It's tricky, but to a first approximation, we make our hypotheses about the world output predictions, and we reduce our confidence in the hypotheses that make worse predictions (a). The book Superforecasting is a neat introduction to the practices involved. E.T. Jaynes' Probability Theory: The Logic of Science is a hardcore introduction to the math behind it. Both books are probably available for free in the z library (a).

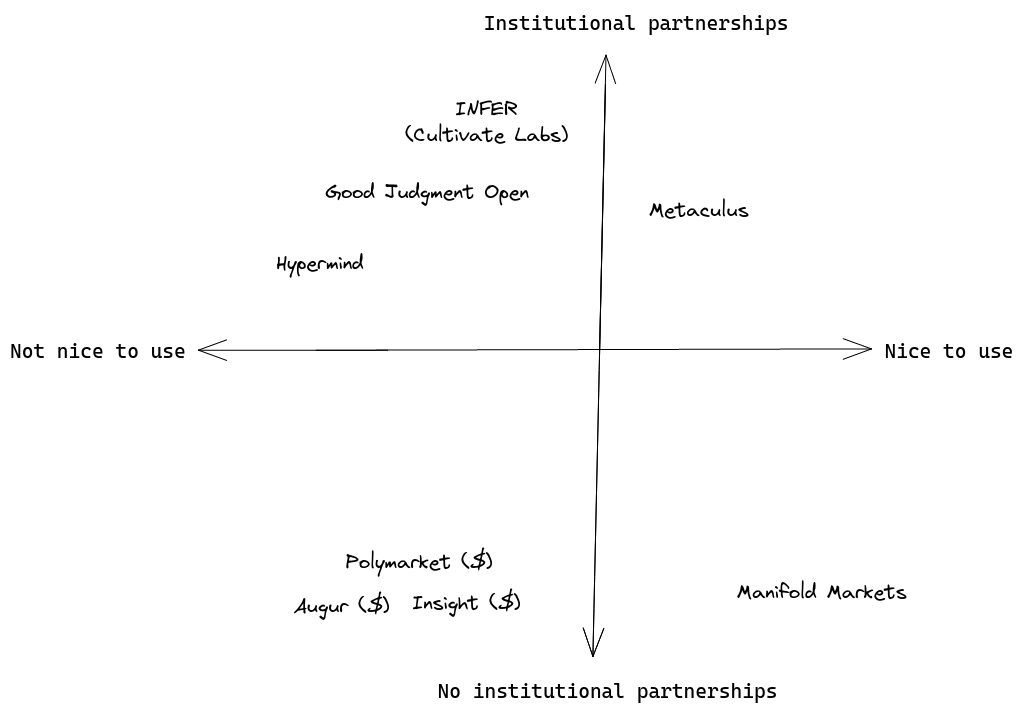

You could keep track of your probabilities in a spreadsheet. But it would also be convenient to collaborate and compete with others. And here come various forecasting platforms, like Metaculus (a), Manifold Markets (a), Good Judgment Open, or INFER. These forecasting platforms struggle to seduce forecasters into tracking their probabilities on their site and get the funds of decision-makers who want to use probabilities to make better decisions.

Besides forecasting platforms, we also have real-money prediction markets, where participants bet their own money on their degree of belief. These can either be based on cryptocurrencies, like Polymarket (a), Insight prediction (a), Hedgehog (a), or be regulated, like Betfair, Kalshi, Nadex or PredictIt. Historically, prediction markets have focused on sports, but in recent times, they have also hosted more informative markets, e.g., on covid, the invasion of Ukraine, and various US political developments.

To my new Spanish readers, I would recommend that you start forecasting on Metaculus and only consider trying prediction markets once you’ve proven to be good in platforms that don’t risk real money.

Something that has been on my mind is that forecasting platforms tend to either have institutional partnerships or be nice to use. But generally not both. I think this can be explained by older websites using worse technology but having had more time to develop partnerships:

I generally tend to take a technology maximalist perspective toward that tradeoff in this newsletter. I tend to express the view that platforms with better technology will outcompete the others because they will be able to move and experiment faster, add new features, and retain more users.

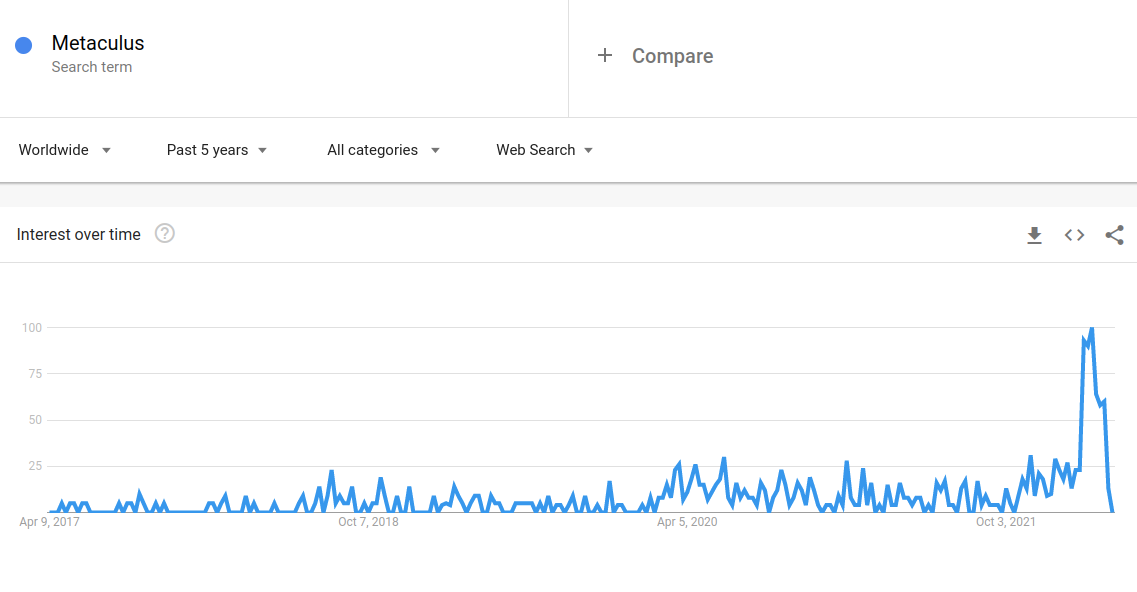

Recently, two interesting developments have been affecting the forecasting ecosystem. First, the war between Russia and Ukraine has sparked broader interest in whether forecasting platforms or prediction markets have anything to say about it:

And secondly, the FTX Future Fund (a), a very large philanthropic funder, has expressed interest in forecasting. Platforms and individuals in the space have been scrambling to present proposals that might please it.

And with this, we are left to discuss recent developments:

Notable news

Pricing existential risk (see aso: existential risk (a)): All investments go to zero in the case of existential risk, so it's hard to price it correctly. In particular, one can't just substitute riskier assets with less risky assets. Still, the higher the existential risk is, the more one should frontload consumption. And if stocks are roughly worth the discounted value of dividends and other payments, higher existential risk should reduce their value. But the market may not have realized this yet. I thought that the article was great, but I would have appreciated a more comprehensive treatment.

The Forecasting Wiki (a) is getting started. As advertised on their website, they have a meetup on April 24th, as well as a Discord channel.

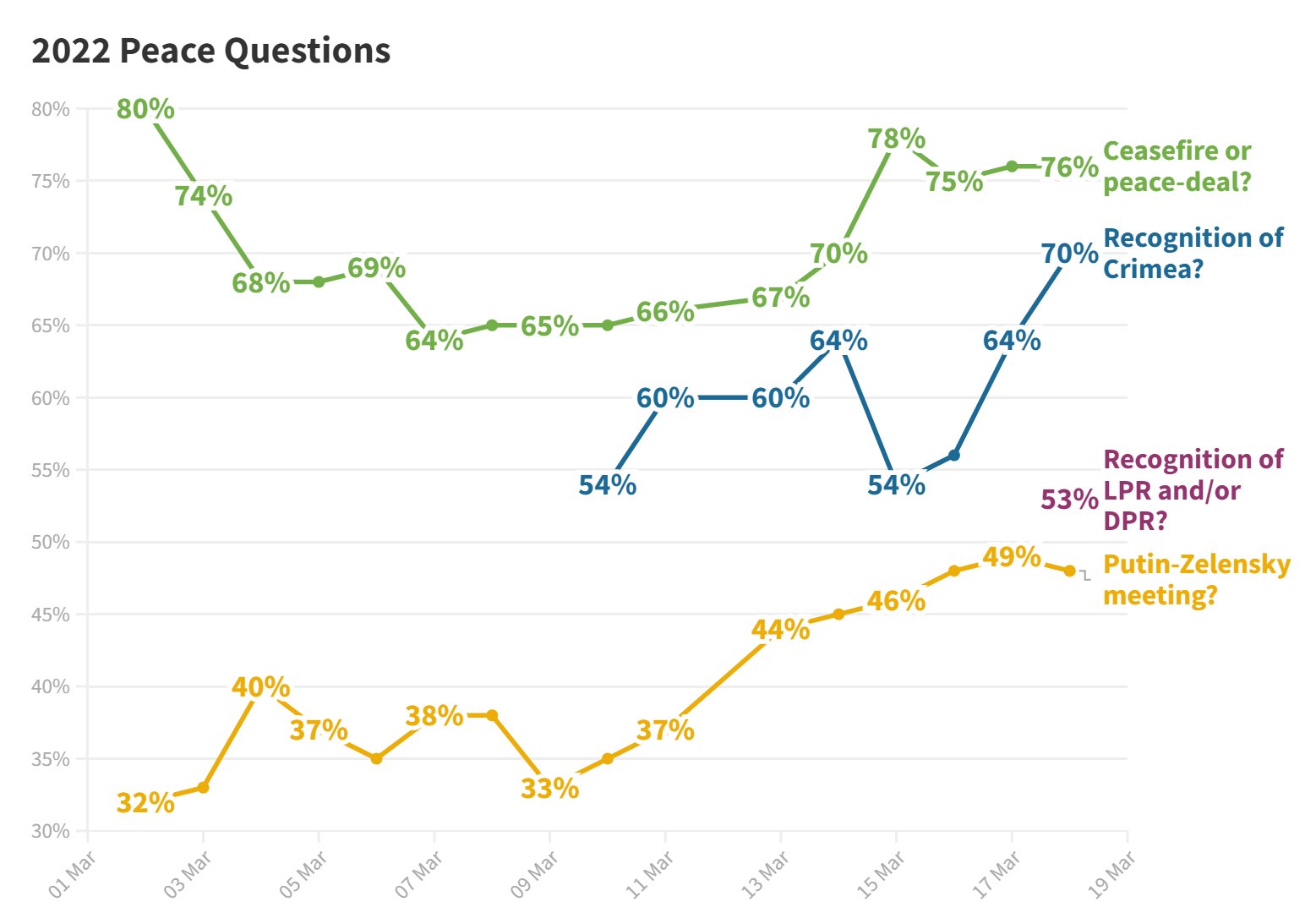

Global Guessing continues to do a great job following developments in the Ukraine war through shifts in probabilities. For example:

Platform by platform

Metaculus continued publishing questions on the Ukraine conflict (a), estimated low meat production (a) and organized a small White Hat cybersecurity tournament (a), which got picked up by Lawfare (a)

Per SimonM, the most insightful comments on Metaculus were:

- orion.tjungarryi looks at the relationship between population and how long cities hold out, to figure out whether Kiev would fall. The larger the cities, the longer they tend to hold.

- haukurth: "It's a full time job now to constantly degrade Russian chances on various Metaculus questions."

- aqsalose calculates a base rate for regime change in Russia. Based on historical precedent, Putin's grip on power doesn't look to bad in the short term.

- Joker also looks at the base rate of sieges—they last longer than a month. Based on this, he gave a 1% chance of Kiev falling at a time when the Metaculus aggregate was at ~65%.

I also liked Richard Hanania's Metaculus notebook on Why Forecasting War is Hard (a).

Good Judgement Inc is hiring a Director of Sales (a).

Manifold Markets discusses their market mechanics (a) (technical). Prediction markets need a way to match bets between users. In modern times, they do so by betting against a central automated market-maker, but different algorithms determine the specifics. Manifold Markets tells how they started with Dynamic Parmimutuel, considered the logarithmic market scoring rule, and ended up with a less elegant constant product market maker.

Manifold also implemented loans on the first M$20 bet on any market (a), applied to the FTX Fund (a), and awarded some bounties to active community members (a).

INFER is organizing a tournament for EA university groups (a). I would recommend joining; I enjoyed their team functionality.

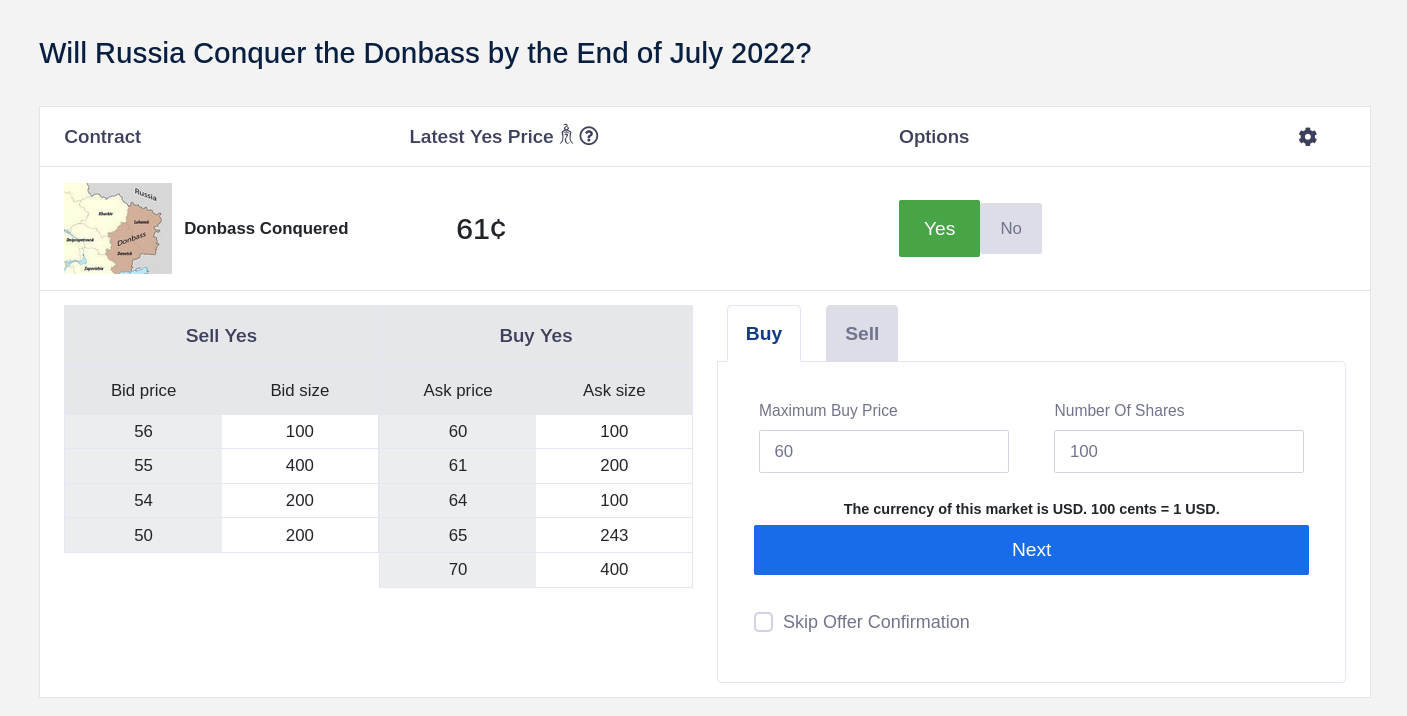

Insight predictions (a) continues to have the guts to ask the important questions, such as: "Will Russia Conquer the Donbass by the End of July 2022?". Though liquidity (the opportunity to trade on both sides of a question) is a bit thin.

The ¿founder? of Insight Predictions also objected (a) to me characterizing Insight as possibly but most likely not a scam in a previous newsletter. One of the key elements that made me suspicious was that he had previously remained anonymous. But he has now de-anonymized himself, and he turns out to be Douglas Campbell, who previously served in Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors. So there’s that.

Kalshi (a) and Polymarket (a) offer markets on interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve. This seems like an interesting hedge.

Hypermind has a small $5k tournament on African developments (a)

Polymarket has been offering rewards for trading. Trading incurs a fee, but trading rewards are higher, which incentivizes wash trading (trading back-and-forth at high volumes.) The thing is, Polymarket developers are not stupid, so I'm guessing that they are doing this because they want the volume to be as high as possible ¿possibly to impress or appease investors? The non-nefarious explanation is that they deeply want to attract new traders and keep the engagement of old ones, and are ok paying wash traders as the cost of doing business. (edit: apparently not the case, will issue a correction in the next issue)

In any case, I have downgraded my estimates (a) of Polymarket prediction quality as a function of volume for Metaforecast. Metaforecast (a) itself is doing great, with a bit over 15k views a month. I've also recently hired an extremely competent developer (a) to continue working on the project. So far, he has been leaving the codebase in a much better position, solidifying and professionalizing parts that were previously more glued together with ducktape. Feature ideas are welcome!

Spose (a) (pronounced like "I suppose", I'm guessing) is a smallish platform to "casually forecast serious stuff". They ask one very short-term question every day.

Research

Comparing top forecasters and domain experts (a) reviews the idea that the very best generalist forecasters can beat experts at predicting events in their own domain of expertise.

In particular, there is an oft-cited refrain that "superforecasters are 30% better than experts with access to classified information". But the authors find that a large share of the difference may boil down to different aggregation methods: "The forecaster prediction market performed about as well as the intelligence analyst prediction market; and in general, prediction pools outperform prediction markets in the current market regime (e.g. low subsidies, low volume, perverse incentives, narrow demographics)."

The CEO of Good Judgment Inc answers in the comments (a): "These claims about Superforecasting are eye-catching. However, it's difficult to draw any conclusions when most of the research cited doesn't in fact include Superforecasters". But this seems inconsistent with the eye-catching 30% claim on Good Judgment's own website.

My forecasting group recently estimated the risks of nuclear war (a). We arrived at a 24 in a million chance that an "informed and unbiased" Londoner would be hit by a nuclear blast in the next month. This estimate was picked up by Scott Alexander (a) and the Spanish press (a)

Now a subject matter expert who served as deputy staff director of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations where he worked on approval of the New START agreement, critiziced our estimates (a). Our answer can be seen in the comments (a).

Why short-range forecasting can be useful for longtermism (a)

I argue that advances in short-range forecasting (particularly in quality of predictions, number of hoursted, and the quality and decision-relevance of questions) can be robustly and significantly useful for existential risk reduction, even without directly improving our ability to forecast long-range outcomes, and without large step-change improvements to our current approaches to forecasting itself (as opposed to our pipelines for and ways of organizing forecasting efforts).

To do this, I propose the hypothetical example of a futuristic EA Early Warning Forecasting Center. The main intent is that, in the lead up to or early stages of potential major crises (particularly in bio and AI), EAs can potentially (a) have several weeks of lead time to divert our efforts to respond rapidly to such crises and (b) target those efforts effectively.

In Cryptoepistemology (a), davidad maps different theories of justified beliefs to different styles of cryptographic proof.

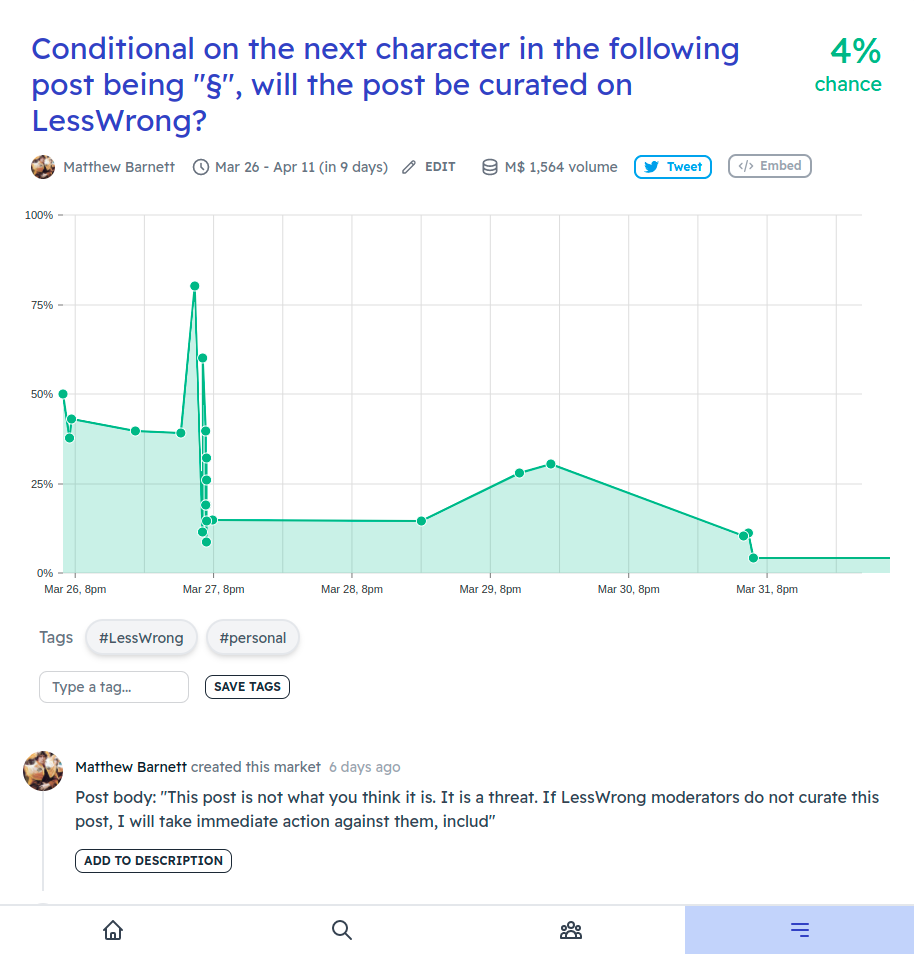

Lastly, I really enjoyed two prediction-market related April Fool's jokes: Using prediction markets to generate LessWrong posts (a) and Anti-Corruption Market (a). I'm also pretty proud of my own April Fool's: Forecasting Newsletter: April 2222 (a).

Note to the future: All links are added automatically to the Internet Archive, using this tool (a). "(a)" for archived links was inspired by Milan Griffes (a), Andrew Zuckerman (a), and Alexey Guzey (a).

y en el mundo, en conclusión,

todos sueñan lo que son,

aunque ninguno lo entiende.

English translation:

and in the world, in conclusion,

they all dream what they are

although none of them understands it

Fragment of Segismundo’s monologue, in La vida es sueño, from Spanish playwright Calderón de la Barca.

You may be interested in reading my long-form (albeit meandering) thoughts on this exact issue! Here is the post, wherein I analyze and respond to an essay by Peter Thiel on this same subject of the interaction between markets and apocalyptic risks that would end those very markets. Among other things, I wonder if (precisely because markets are incentivized to ignore X-risk), we can somehow use markets (including specially-created prediction markets) to indirectly measure X-risk or related quantities.

On the subject of Hanania's "Why War Forecasting is Hard", I'm surprised that he didn't mention the unpredictable effects of... I'm not sure what to call this, maybe "preference cascades" or just the nature of coalitional fights? Experts & forecasters alike were surprised on the downside at how quickly the Afghanistan army gave up against the Taliban, and they were surprised on the upside at how stalwart the Ukrainian forces have been against Russia. I don't think this is all just the physical complexity of war (ie, the difficulty of assessing whether tire maintenance is a crucial factor) or the difficulty of assessing deep cultural factors ("are Ukranians too westernized to be willing to fight", "do Russians really consider Ukraine a part of their ancestral homeland", and similar). It seems like the decision of whether to fight or give up is perhaps just a volatile and uncertain thing, dependent on social perception of which way the wind is blowing and whether other people have decided to fight or give up.

ie, in another universe, if for whatever reason more Ukrainian leaders had fled the country (perhaps the government relocates from Kiev to Lviv) and there were fewer early stories of heroic resistance (like the tales about Snake Island, etc), perhaps many Ukranians would have started giving up and Russia would have had much more success with their invasion, despite no change whatsoever in the fundamental factors (military hardware or cultural stuff or etc). This is just my own pundit-like speculation, I know, but it strikes me as perhaps a more plausible explanation of why war forecasting might be especially/uniquely tricky, compared to other similarly complex things like forecasting the success of a new rocket's first launch or the growth of a nation's economy -- rockets and economies can be just as vexing as unmaintained tires!

Thanks for this newsletter, and congrats on getting to 1000!

Cheers