This post was written for Convergence Analysis.

Summary

A person’s “moral circle” classically refers to the entities that that person perceives as having moral standing, or as being worthy of moral concern. And “moral circle expansion” classically refers to moral circles moving “outwards”, for example from kin to people of other races to nonhuman animals, such that “more distant” entities are now in one’s “circle of concern”.[1]

This overlooks, or at least fails to make explicit, two important complexities. Firstly, a person may view two entities as both being worthy of some moral concern, but not the same amount of moral concern. This could be due to perceived differences in the entities’ capacities for welfare, moral status, or probability of moral standing.

Secondly, there are many distinct dimensions along which moral circles can expand, such as genetic difference, geographical distance, and distance in time. A person’s moral circle may be “larger” than another person’s in one dimension, yet smaller in another. For example, one person may care about all animals in the present but few beings in the future, while another cares about humans across all time but no nonhuman animals.

This post expands on these complexities, and shows how they can be captured visually. It mirrors or draws on many ideas from prior sources related to moral circles and their expansion.

I hope this post can facilitate better thought about, discussion of, and visualisation of moral circles and related matters. That, in turn, should be useful for reasons including the following:

- A key feature of EA is trying to help beings who are often left out of other people’s moral circles (e.g., the global poor, nonhuman animals, and future generations). Better understanding of moral circles and their expansion may aid us in determining which beings to try to help (including identifying groups we may be neglecting; see also Dewey), and in increasing how many resources other people dedicate towards benefitting neglected beings.[2]

- Many important problems (e.g., AI safety, improving “wisdom” or “rationality”) depend in part on gaining a better understanding of one’s own or other people’s values, and/or how these values will or should develop. Moral circles play a key part in people’s values, so better understanding moral circles and their expansion should aid in addressing those problems.

The classic view of moral circles

In The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution, and Moral Progress, Peter Singer wrote:

The circle of altruism has broadened from the family and tribe to the nation and race, and we are beginning to recognize that our obligations extend to all human beings. The process should not stop there. [...] The only justifiable stopping place for the expansion of altruism is the point at which all whose welfare can be affected by our actions are included within the circle of altruism.

This “circle of altruism” is more commonly referred to as “humanity’s moral circle”. It also makes sense to speak of the “moral circles” of specific people or groups, given that people differ in how “large” their moral circles are. For example, perhaps Alice’s moral circle includes only herself and her family, while Bob’s moral circle includes all animals (including all people).

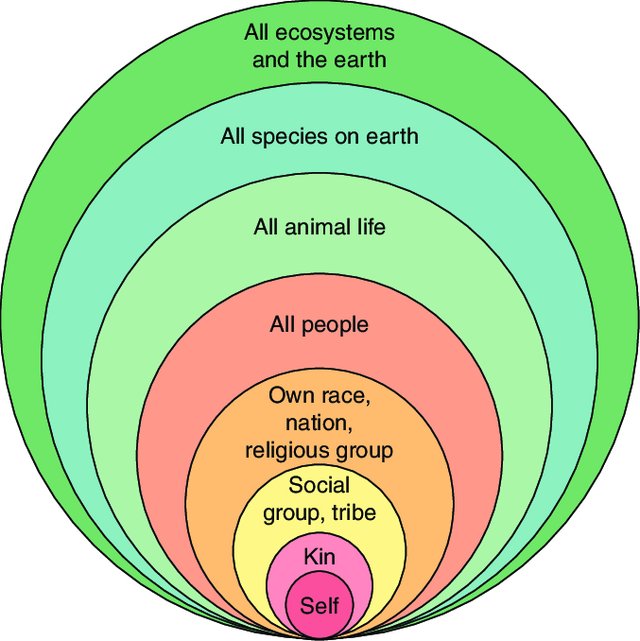

These moral circles are classically visualised roughly as follows (source):

(Note that different visualisations differ in which entities they show and what “order” they show these entities in.)

With reference to such a diagram, we could say that Alice’s moral circle includes only the entities in the pink circles, while Bob’s moral circle encompasses all entities in the light green circle (i.e., all animals, including all people).

This may suggest that Alice believes, or will act as if, only herself and her kin are moral patients - in other words, as if they’re the only entities who have moral standing; who have “intrinsic moral worth”. Meanwhile, Bob may believe, or act as if, all animals have moral standing. (That said, Alice and Bob may not think in these terms, and there may be inconsistencies between their actions and their beliefs.)

Moral concern can differ by degree

But what if Bob cares about the interests and welfare[3] of both humans and nonhuman animals, but cares more about the interests and welfare of humans? Crimston et al. note that:

“Moral concern” can span from believing an entity’s rights and well-being take precedence over all other considerations, to a perception that their needs and rights are worthy of limited consideration without being a primary concern.

Discussions of moral circles could either be just about whether an entity is perceived as warranting moral concern, or also about how much concern an entity is perceived as warranting. It seems valuable to explicitly state which of these conceptualisations one is using, to avoid confusion (see also Moss). It also seems most valuable to use the latter conceptualisation, given that it does seem people very often think in terms of degrees of moral concern, rather than just binary distinctions.

There are three things that may justify a person having more concern for one entity than another:

-

The person might believe the entities likely differ in their capacity for welfare.

- For example, one might argue that a cow can experience greater peaks and troughs of welfare than an ant can.

-

The person might believe the entities likely differ in their moral status.

- Schukraft writes: “For our purposes, I’ll let moral status be the degree to which the interests of an entity with moral standing must be weighed in (ideal) moral deliberation or the degree to which the experiences of an entity with moral standing matter morally.”[4]

- For example, one might think the same amount of welfare matters less if it is bestowed upon future generations than if it is bestowed upon the present generation (even if all other factors, such as wealth, are held constant).

-

The person might be more certain that one entity has moral standing than that the other does.

- For example, one might think there’s a 100% chance that the welfare of “natural” human minds matters, but only a 25% chance that the welfare of digital minds matters.[5]

Of course, people will rarely use these precise terms in their own thinking. Furthermore, many people will probably never think explicitly about how much moral concern they have for various entities, or about what factors have influenced that.

Visualising degrees of moral concern

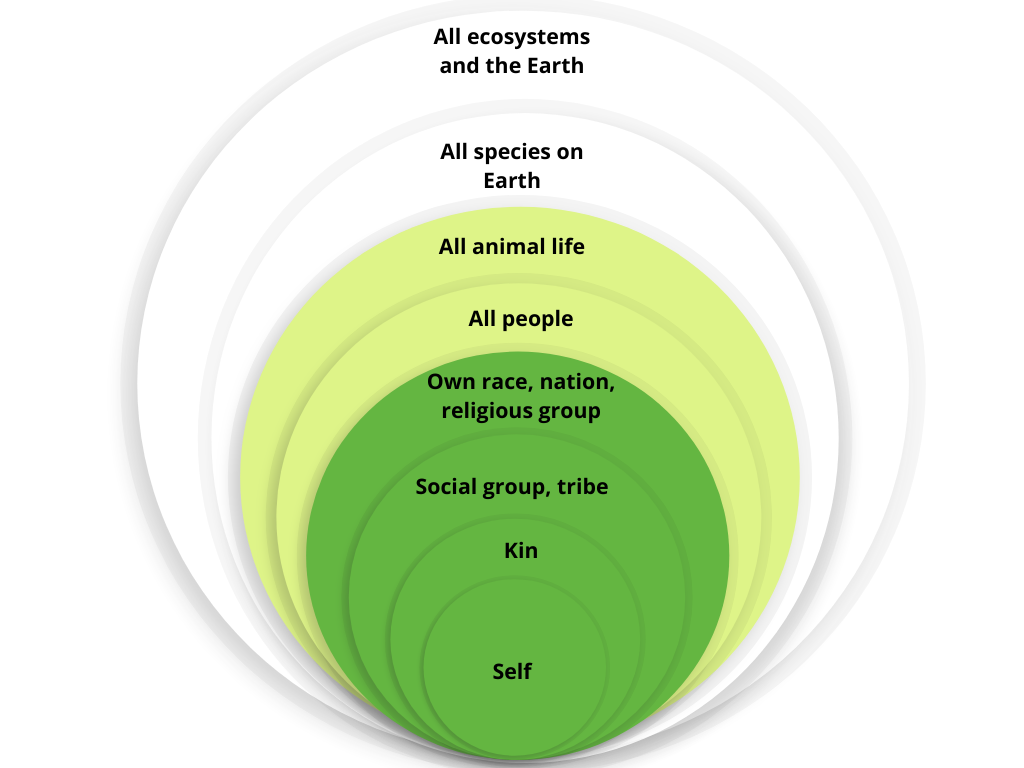

Whatever the reason for differences in degree of moral concern granted to different entities, we can visualise such differences using circles of different colours (or different opacity). For example, let’s say that Carla:

- is practically certain that members of her own race, nation, and religious group are worthy of substantial moral concern

- sees it as plausible that the same is true of other people and animals, or sees it as practically certain that other animals are worthy of some but less moral concern (either due to having lower capacity for welfare or lower moral status)

- sees other entities as worthy of no or negligible concern, or sees the chance that they’re worthy of concern as negligible

We could represent this with a dark green circle for the first “level” of moral concern, a light green circle for the second level, and no colouring for the third level, as shown here:

If we wished, we could also represent things more continuously, by using gradual shifts in shading or opacity, or by adapting the “heat map” approach used in Figure 5 of this paper.

“Moral circles” are multidimensional

Grue_Slinky writes:

From a certain perspective, one could view effective altruism as a social movement aimed at getting society to care more about groups that it currently undervalues morally. These groups include:

1. People living far away spatially

2. People living far away temporally

3. Animals used by humans

4. Wild animals

5. Digital minds + certain advanced reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms

The author relates this to discussion of moral circle expansion (MCE), and writes:

When I've thought about the moral circle naively, I've imagined a coordinate system with

"Me" at the origin

People I know represented as points scattered around nearby

People of my own nationality/ethnicity/ideology as points somewhat further out

The other groups (2-5) being sets of points somewhere further out

where the "distance from the origin" of a mind simply represents 'how different' it is compared to mine, and consequently [how difficult] it is to empathize/sympathize with it. And under this view, I've conceived of moral circle expansion (MCE) as merely the normative goal of growing a circle centered around the origin much like inflating a balloon.

But the author notes that “the moral circle does not necessarily expand uniformly”, and writes of “The Many Facets of MCE”:

[Groups (1-5)] are "weird" or "far" from our own minds, but they are far in different and often incomparable ways. For EAs, each of these 5 undervalued groups lend themselves to a particular problem of the form "How do we get society to care more about X?".

The author lists various dimensions along which moral circles can expand, and states:

For each of these dimensions, we can try to push the moral circle outward in that dimension. I call this domain-specific MCE.

If moral circles were one-dimensional, any MCE might seem likely to increase the chances that any other type of entity will ultimately be included in people’s moral circles. But since moral circles are multidimensional, if a person primarily cares about increasing moral concern for a particular type of entity (e.g., future people, digital minds, wild animals), it might be important to think about which dimensions a given intervention would expand moral circles along.

Relatedly, due to the multidimensionality of moral circles, two people could have differently shaped “moral circles”, winding through the space of relevant dimensions in different ways, rather than just differently sized moral circles. The terms “moral boundaries” and “moral boundary expansion” might therefore be more appropriate than “moral circles” and “moral circle expansion”. For this reason, the remainder of this post will switch to using the former terms.[6]

Visualising multidimensional moral boundaries

I’ll now show how we can visualise moral boundaries in multiple dimensions.

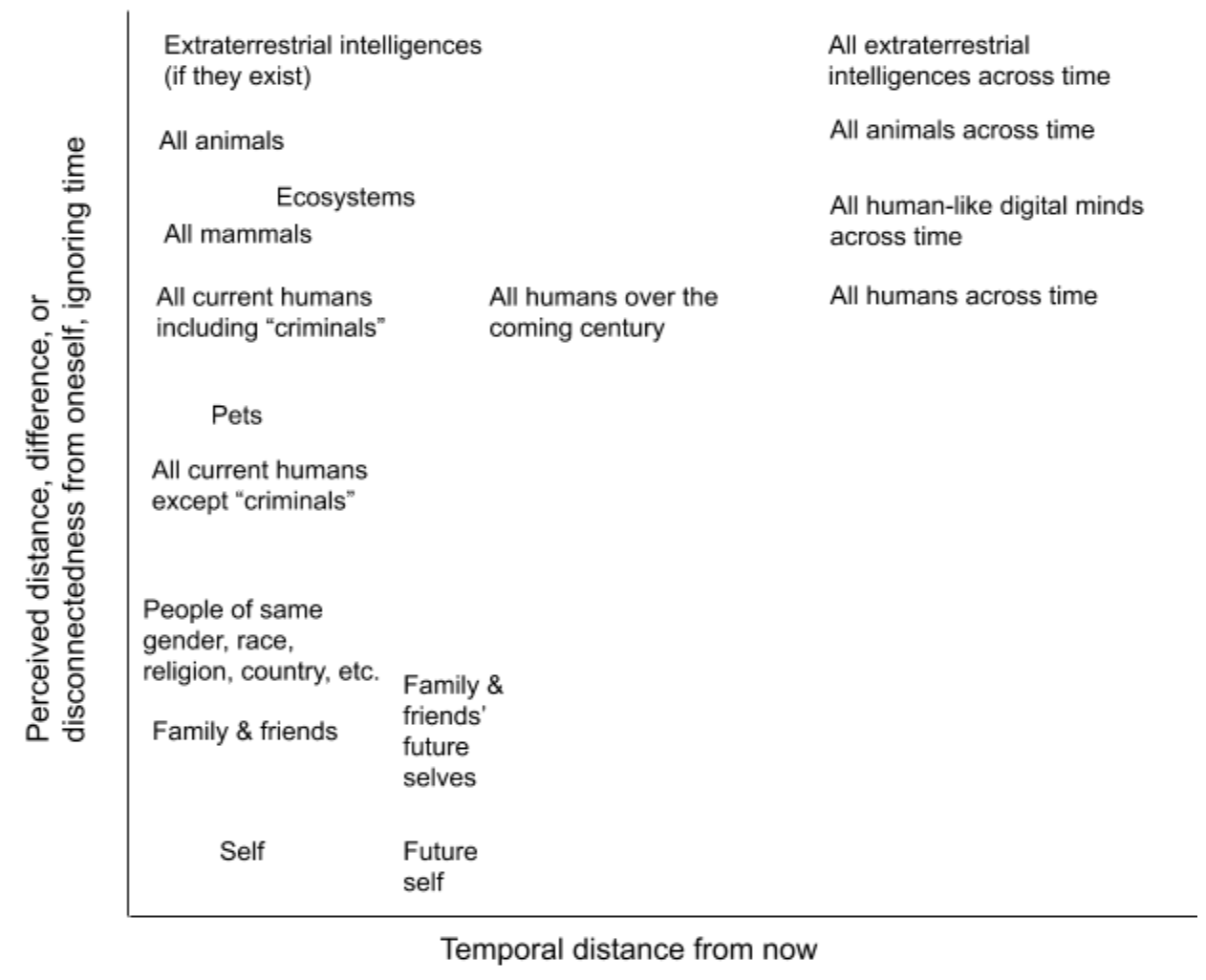

Let’s start with just two dimensions:

-

Temporal distance from now

- I.e., how long there will be between (a) the present and (b) the existence of, or effects on, the entity in question

-

Perceived distance, difference, or disconnectedness from oneself, ignoring time

This second dimension collapses together a vast array of things. It is meant as something like a catch-all for everything typically considered in discussions and visualisations of moral circles outside of EA (as temporal distance is typically overlooked in those discussions and visualisations[7]).

And let’s start by visualising the locations of various types of entities in the space formed by those two dimensions. (Of course, this is all purely for illustration; the choice of which types of entities to show was fairly arbitrary, and their locations in this space are approximate and debatable.)[8]

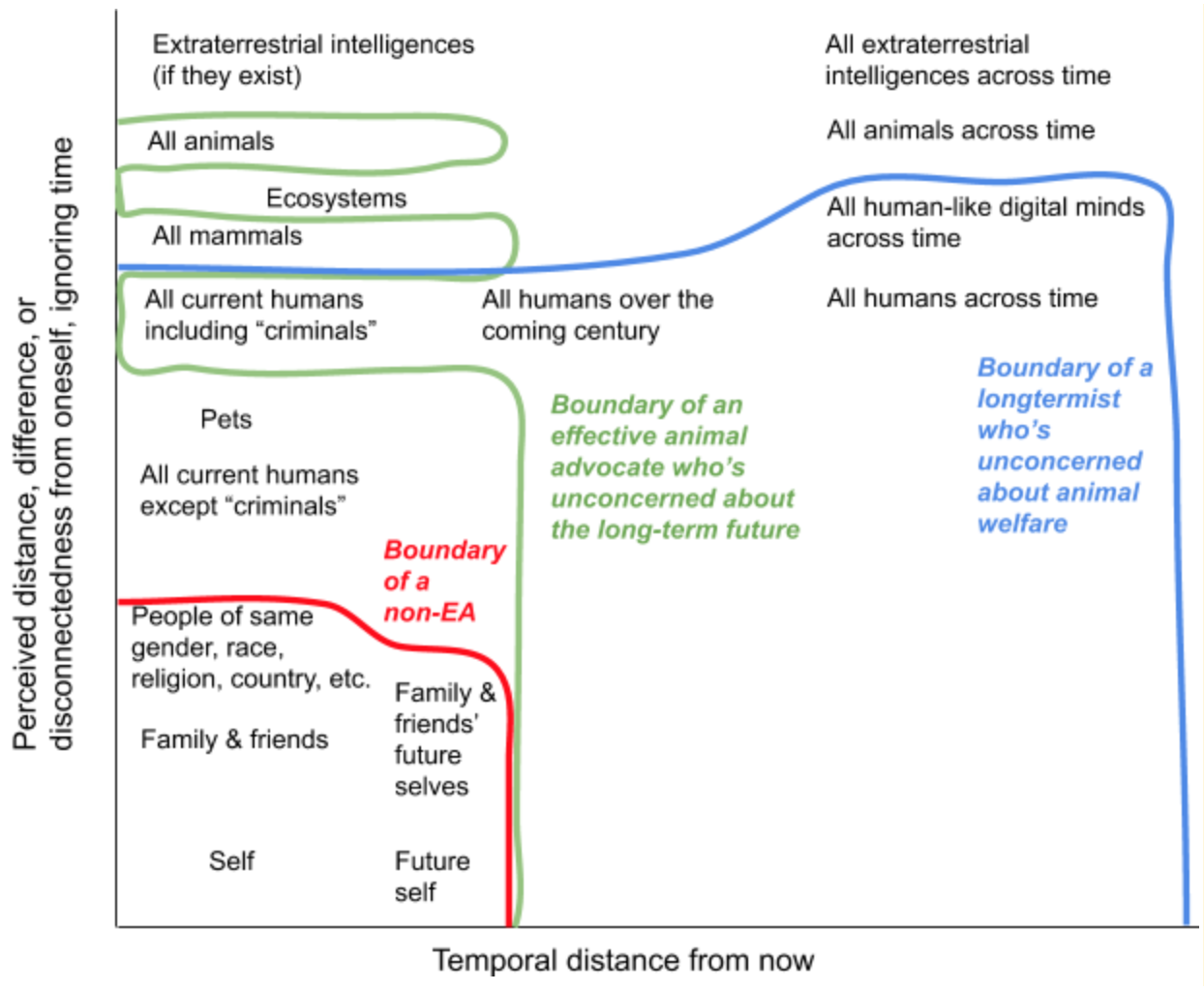

We can then represent not just the size but also the particular shape of a person’s moral boundaries. For example:[9]

This multidimensional approach to visualising moral boundaries helps us see that a person’s moral boundaries can:

-

be more expansive in one dimension than another person’s moral boundaries, yet equally or less expansive in another dimension (rather than just being “bigger” or “smaller” overall)[10]

-

“skip” entities in one section of a given dimension, but include entities on either side of that section

-

For example, this hypothetical effective animal advocate’s moral boundaries don’t include “criminals” or ecosystems, but do include some entities that are either lower or higher on the y axis.[11]

This “skipping” may typically or always result from a graph failing to explicitly represent dimensions that are relevant to a person’s moral boundaries. For example, the “skipping” shown in that hypothetical effective animal advocate’s moral boundaries may result from the EA also caring about an entity’s perceived levels of blameworthiness and sentience, which are dimensions “criminals” and ecosystems (respectively) score worse on than animals do.

It will therefore often be useful to think of moral boundaries as being determined by, expanding along, and/or contracting along more than two dimensions. Beyond three dimensions, this can’t be easily visualised, but it can still be loosely imagined.[12] We can think of moral boundaries as n-dimensional shapes existing in n-dimensional space, where “n” is however many dimensions one chooses to consider as relevant. And we can imagine an n-dimensional function that takes an entity’s “score” on each dimension as input, and outputs either whether that entity is worthy of concern, how much concern the entity is worthy of, or how likely that entity is to be worthy of (varying levels of) concern.

Dimensions along which moral boundaries may vary, expand, and contract

There are a vast array of dimensions that (a) entities vary along, and (b) could conceivably or in practice be relevant to whether that entity is given moral concern by various people. Which dimensions are relevant to whether an entity is given moral concern, and the relative significance of each, is ultimately an empirical question that won’t be addressed in this post. Instead, this post will list a range of dimensions that seem to be plausibly relevant.

Some things worth noting:

-

This list is not comprehensive.

-

Some of these dimensions may overlap or be correlated with each other.

- For example, species and level of intelligence.

-

Some “dimensions” may in fact be best thought of as categorical or ordinal.

- For example, “species” could perhaps be thought of as something like “human vs not”, or a list of species ranked by how “worthy of concern” they’re typically perceived as being.

-

Each of these dimensions may be best thought of in terms of how the perceiver perceives the entity, rather than the “actual” properties of the entity.

- For example, a perception that pigs have a low intelligence, rather than pigs’ actual intelligence levels, may play the larger role in whether pigs are deemed worthy of concern.

-

It may often make sense to think of distance from a perceiver along a given dimension, rather than just location on that dimension

- For example, how different an entity’s values or goals are to one’s own, rather than just what those values or goals are.

-

In cases where I know of another source that has mentioned (something like) one of these dimensions as potentially relevant to moral circles or moral boundaries, I’ll provide a link to that source.

With that in mind, here is our current list of plausibly relevant dimensions:

-

Genetic relatedness to self and/or “evolutionary divergence time”

-

“Connectedness” to self (social, cultural, etc.)

-

Level of various kinds of sentience, consciousness, or susceptibility to pleasure and/or pain (see Muehlhauser)

- This could itself be split up into multiple dimensions, of course.

-

Level of intelligence (see Grue_Slinky)

-

Level of various other mental abilities (e.g., abstract thought, creativity, self-awareness; see Schukraft)

-

Species (see Sentience Institute), or human vs not (see Grue_Slinky)

-

Physical location (see Sentience Institute)

-

Temporal location (see Sentience Institute)

-

Sex/gender, sexual orientation, or related matters

-

“Naturalness”, “centrality to ecosystems”, or similar[14]

-

Innocence (as opposed to blameworthiness, or deservingness of suffering)

-

Spiritual or cultural significance[15]

-

Substrate (see Sentience Institute)

-

Inclusion in one’s diet, or in a “typical” diet in one’s culture (see Grue_Slinky)

-

Cuteness (see Grue_Slinky)

-

“Pests vs. helpers: Bees are valued more than locusts” (Grue_Slinky)

-

Values or goals

-

“Weirdness” in various senses (e.g., how unusual the entity’s type of mind or physical form is)

-

Rarity / endangered species status

-

Physical size (see Grue_Slinky)

-

Beauty, appearance, and/or awe-inspiringness

- E.g., some people may be more likely to see the Grand Canyon as worthy of moral concern than a less “beautiful” or “striking” non-sentient entity.

Conclusion

Better conceptualisation, visualisation, and empirical data related to moral circles/boundaries (and their expansion) could help in various efforts to improve the world. For example, this may help in identifying more neglected populations, in spreading longtermism and thereby increasing the resources dedicated to existential risk reduction, or in understanding human values for the purposes of AI alignment. To that end, this post:

- summarised relevant ideas from prior work

- highlighted in particular the often overlooked points that moral concern can differ by degrees and that moral boundaries are not one-dimensional

- suggested ways of visualising moral boundaries that can take into account these complexities

- listed dimensions along which moral boundaries may vary, expand, and/or contract

There are of course many questions related to moral boundaries that this post did not explore. Each of these questions have been partially addressed by at least some prior work (such as these works), though they seem likely to still be fruitful avenues for further work.

-

What are all of the (most important) dimensions along which moral boundaries vary, can expand, or can contract? How important is each dimension?

-

What are the correlations between expansiveness (or expansions) of a person’s moral boundaries along different dimensions?

-

How expansive should our moral boundaries be, along each dimension?

-

What are the factors which most commonly influence the expansiveness of people’s moral boundaries along various dimensions? What are the factors that could be most cost-effectively influenced?

- E.g., philosophical arguments about the importance of impartial altruism to all sentient beings? Whether people have access to clean meat? Movies depicting future generations?

-

What factors other than inclusion in people’s moral boundaries (or degree of moral concern granted) determine people’s beliefs about how a given entity should be treated?

- E.g., a distinction between doing and allowing harm, scope neglect, and status quo bias.[16]

My thanks to Justin Shovelain, Jason Schukraft, Jamie Harris, Clare Harris, John Welford, and Linh Chi Nguyen for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this post, and to Courtney Henry and Grue_Slinky for discussions that helped inform the post. This does not imply these people’s endorsement of all of this post’s claims.

“Moral circle expansion” can also refer to the activity of trying to cause people’s moral circles to expand. ↩︎

Note that this post does not take a stand on:

- How expansive moral circles should be.

- How important, tractable, neglected, or “zero-sum” moral advocacy is. (Moral advocacy includes moral expansion work.) For discussion related to those points, see Christiano and Baumann.

I’m using “welfare” in an “expansive sense in which a subject’s welfare is constituted by whatever is non-instrumentally good for the subject, whether experiential or non-experiential” (Schukraft). No part of this post depends on accepting a hedonistic theory of welfare, an emphasis on sentience, or utilitarianism. ↩︎

Another relevant term is moral weight. This seems to typically refer to capacity for welfare, moral status, or some combination of the two.

Note that Schukraft’s post merely discusses the idea that moral status could differ by degree between entities, rather than endorsing that idea. ↩︎

It could perhaps be valuable to have a notion of “expected moral concern”, or “expected moral weight”, which is a product of capacity for welfare, moral status, and probability of moral standing (or perhaps a product of a probability distribution over capacity for welfare and a probability distribution over moral status). ↩︎

The reason I used the term “moral circles” for the title and the earlier parts of this post is that that is currently the more established term (although the term “moral boundaries” is used in at least one recent academic paper). This is a good reason to use the term “moral circles” at least sometimes, and perhaps typically or as the default, even if it might’ve been better if the term “moral boundaries” had been used universally from the start.

It’s also worth noting that the word “circles” in “moral circles” can of course just be interpreted non-literally, analogously to how it is used in the phrases “my social circle” or “my circle of friends”. My thanks to Jason Schukraft for this point. ↩︎

That failure to consider temporal distance seems a major and unfortunate oversight, both from the neutral, scientific perspective of understanding people’s moral boundaries, and from the perspective of using this understanding to address pressing global priorities related to longtermism and existential risks. Helping prevent such oversights is one reason it may be valuable to conceptualise moral boundaries multidimensionally. ↩︎

Another issue with these diagrams: In some positions, a label is used that would technically include a group or type of entity which is already represented elsewhere in the diagram. For example, “All humans across time” would technically include “All humans over the coming century”, and “Self”. But one could conceivably care about all humans across time except for those in the coming century, or except for oneself.

However, I couldn’t think of an instance in which that sort of pattern of moral concern would be likely in practice, so I opted to avoid cluttering the diagram with more precise labels (e.g., “all humans from 100 years from now onwards, not including oneself”). ↩︎

The moral boundaries shown here are purely illustrative; I don’t mean to imply that these show what the boundaries would be for a “typical” non-EA, a “typical” effective animal advocate who’s unconcerned about the long-term future, or a “typical” longtermist who’s unconcerned about animal welfare.

For simplicity, in this diagram I haven’t represented different degrees of moral concern (e.g., seeing entities closer to the present as worthy of more moral concern). But one could do so using the same methods discussed earlier in the main text (namely, showing multiple boundaries with different colours, or showing a gradual shift in shading or opacity). ↩︎

That said, I do expect that, in practice, there will be correlations between the expansiveness of people’s “moral boundaries” across multiple “dimensions”. And Crimston et al.’s findings appear to provide some evidence of this. Precisely how strong these correlations are, how this differs for different dimensions, and how it differs for different respondents (e.g., people who have vs haven’t thought a lot about moral philosophy) are empirical questions which this post will not address. ↩︎

One way to put this: Moral concern doesn’t necessarily decrease monotonically as we move along a given dimension, despite what one might assume. Instead, it can sometimes increase in one section after having decreased in another. ↩︎

That said, some approaches to visualising more than three dimensions do exist, such as radar charts. ↩︎

It should be noted that Schukraft provided relevant quotes, rather than making relevant claims himself, and that the quotes were most relevant to moral status rather than to moral boundaries. ↩︎

My thanks to Jamie Harris for suggesting I add this dimension. ↩︎

My thanks to John Wentworth for suggesting I add something similar to this dimension and the “Rarity / endangered species status” dimension. ↩︎

I think that these factors could be represented as dimensions along which moral boundaries can expand, but that it would probably be an awkward stretch to do so. For example, the doing/allowing distinction could be represented as a dimension like “Extent to which the entity’s wellbeing vs suffering is or would be “caused by us” or “our responsibility”. (See also Sentience Institute.) ↩︎

[ETA: I've now posted a more detailed version of this comment as a standalone post.]

(Personal views, rather than those of my employers, as with most of my comments)

Above, I wrote:

Here's perhaps the key example I had in mind when I wrote that:

Some EAs and related organisations (especially but not only the Sentience Institute) seem to base big decisions on something roughly like the following argument:

---

Premise 1: It’s plausible that the vast majority of all the suffering and wellbeing that ever occurs will occur more than a hundred years into the future. It’s also plausible that the vast majority of that suffering and wellbeing would be experienced by beings towards which humans might, “by default”, exhibit little to no moral concern (e.g., artificial sentient beings, or wild animals on planets we terraform (see also)).

Premise 2: If Premise 1 is true, it could be extremely morally important to, either now or in the future, expand moral circles such that they’re more likely to include those types of beings.

Premise 3: Such MCE may be urgent, as there could be value lock-in relatively soon, for example due to the development of an artificial general intelligence.

Premise 4: If more people’s moral circles expand to include farm animals and/or factory farming is ended, this increases the chances that moral circles will include all sentient beings in future (or at least all the very numerous beings).

Conclusion: It could be extremely morally important, and urgent, to do work that supports the expansion of people’s moral circles to include farm animals and/or supports the ending of factory farming (e.g., supporting the development of clean meat).

(See also Why I prioritize moral circle expansion over artificial intelligence alignment.)

---

Personally, I find each of those premises plausible, along with the argument as a whole. But I think the multidimensionality of moral circles pushes somewhat against high confidence in Premise 4. And I think the multidimensionality also helps highlight the value of:

I think many of the relevant EAs and related orgs are quite aware of this sort of issue. E.g., Jacy Reese from Sentience Institute discusses related matters in this talk (around the 10 minute mark). So I'm not claiming that this is a totally novel idea, just that it's an important one, and that framing moral circles as multidimensional seems a useful way to get at that idea.

(By the way, I’ve got some additional thoughts on various questions in this general area, and various ways one might go about answering them, so feel free to reach out to me if that’s something you’re interested in potentially doing.)

You don't need to agree with premise 3 to think that working on MCE is a cost-effective way to reduce s-risks. Below is the text from a conversation I recently had, where alternating paragraphs are alternating between the two participants.

The brief conversation below focuses on the idea of premise 3, but I'd also note that the existing psychological evidence for the "secondary transfer effect" is relevant to premise 4. I think that you could make progress on empirically testing premise 4. I agree that this would be fairly high priority to run more tests on (focused specifically on farmed animals / wild animals / artificial sentience) from the perspective of prioritising between different potential "targets" of MCE advocacy, and also perhaps for deciding how important MCE work is within the longtermist portfolio of interventions. I can imagine this research fitting well within Sentience Institute. If you know anyone who could be interested in applying to our current researcher job opening (closing in ~one week's time), to work on this or other questions, please do let them know about the opening.

----

"I don't personally see value lock-in as a prerequisite for farmed animals -> artificial sentience far future impact... if the graph of future moral progress is a sine wave, and you increase the whole sine wave by 2 units, then your expected value is still 2*duration-of-everything, even if you don't increase the value at the lock-in point."

"It doesn't seem that likely to me that you would increase the whole sine wave by 2 units, as opposed to just increasing the gradient of one of the upward slopes or something like that."

"Hm, why do you think increasing the gradient is more likely? If you just add an action into the world that wouldn't happen otherwise (e.g. donate $100 to an animal rights org), then it seems the default is an increase in the whole sine wave. For that to be simply an increase in upward slope, you'd need to think there's a fundamental dynamic in society changing the impact of that contribution, such as a limit on short-term progress. But one can also imagine the opposite effect where progress is easier during certain periods, so you could cause >2 units of increase. There are lots of intuitions that can pull the impact up or down, but overall, a +2 increase in the whole wave seems like the go-to assumption."

"Presumably it depends on the extent to which you think there's something like a secondary transfer effect, or some other mechanism by which successful advocacy for farmed animals enables advocacy for other sentient beings. E.g. imagine that we have 100% certainty that animal farming will end within 1000 years, and we know that all advocates (apart from us) are interested in farmed animal advocacy specifically, rather than MCE advocacy. Then, all MCE work would be doing would be speeding up the time before the end of animal farming. But if we remove those assumptions, then I guess it would have some sort of "increase" effect, rather than just an effect on the slope. Both those assumptions are unreasonable, but presumably you could get something similar if it was close to 100% and most farmed animal advocacy efforts seemed likely to terminate at the end of animal farming, as oppose to be shifted into other forms of MCE advocacy."

"Yep, that makes sense if you don't think there's some diminishing factor on the flow-through from farmed animal advocacy to moral inclusion of AS, as long as you don't think there are increasing factors that outweigh it."

Thanks for this comment!

Good point, thanks! Judging only from that paper's abstract, I'd guess that it'd indeed be useful for work on these questions to draw on evidence and theorising about secondary transfer effects.

Yes, I'd agree that this kind of work seems to clearly fit the Sentience Institute's mission, and that SI seems like it's probably among the best homes for this kind of work. (Off the top of my head, other candidate "best homes" might be Rethink Priorities or academic psychology. But it's possible that, in the latter, it'd be hard to sell people on focusing a lot of resources on the most relevant questions.)

So I'm glad you stated that explicitly (perhaps I should've too), and mentioned SI's job opening here, so people interested in researching these questions can see it.

(Having written this comment and then re-read your comment, I have a sense that I might be sort-of talking past you or totally misunderstanding you, so let me know if that's the case.)

Responding to your conversation text:

I still find it hard to wrap my head around what the claims or arguments in that conversation would actually mean. Though I might say the same about a lot of other arguments about extremely long-term trajectories, so this comment isn't really meant as a critique.

Some points where I'm confused about what you mean, or about how to think about it:

I also think an argument can be made that, given a few plausible yet uncertain assumptions, there's practically guaranteed to eventually be a lock-in of major aspects of how the accessible universe is used. I've drafted a brief outline of this argument and some counterpoints to it, which I'll hopefully post next month, but could also share on request.

Yeah, I agree.

For one thing, if we just cut premise 3 in my statement of that argument, all that the conclusion would automatically lose is the claim of "urgency", not the claim of "importance". And it may sometimes be best to work on very important things even if they're not urgent. (For this reason, and because my key focus was really on Premise 4, I'd actually considered leaving Premise 3 out of my comment.)

For another thing, which I think is your focus, it seems conceivable that MCE could be urgent even if value lock-in was pretty much guaranteed not to happen anytime soon. That said, I don't think I've heard an alternative argument for MCE being urgent that I've understood and been convinced by. Tomorrow, with more sleep under my belt, I plan to have another crack at properly thinking through the dialogue you provide (including trying to think about what it would actually mean for the graph of future moral progress to be like a sine wave, and what could cause that to occur indefinitely).

(commented in wrong place, sorry)

Three researchers have now reached out to me in relation to this post. One is doing work related to the above questions, one is at least interested in those questions, and one is interested in the topic of moral circles more broadly. So if you’re interested in these topics and reach out to me, I could also give those people your info so you could potentially connect with them too :)

Hey! As you probably know, I'd be keen to connect with them. Thanks!

Great, I'll share your info with them :)

Here’s a collection of additional sources which may be useful for people interested in learning more about - or doing further work related to - the questions listed at this end of this post, and perhaps especially question 1. (These sources were mentioned by commenters on a draft of this post, and I’ve only read the abstracts of them myself.)

Empathy and compassion toward other species decrease with evolutionary divergence time

Welcoming Robots into the Moral Circle: A Defence of Ethical Behaviourism

How we value animals: the psychology of speciesism

Misanthropy, idealism and attitudes towards animals

Some animals are more equal than others: Validation of a new scale to measure how attitudes to animals depend on species and human purpose of use

What are Animals? Why Anthropomorphism is Still Not a Scientific Approach to Behavior

Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat

Factors Influencing Human Attitudes to Animals and Their Welfare

Update To Partial Retraction Of Animal Value And Neuron Number