Many people have suggested that improving, safeguarding, or promoting liberal democracy should perhaps be a priority for longtermists. For example, 80,000 Hours lists improving institutional decision making, safeguarding liberal democracy and voting reform as potentially high-impact cause areas (Koehler, 2020). However, it remains unclear how high-priority these areas and specific interventions within them are, and why.

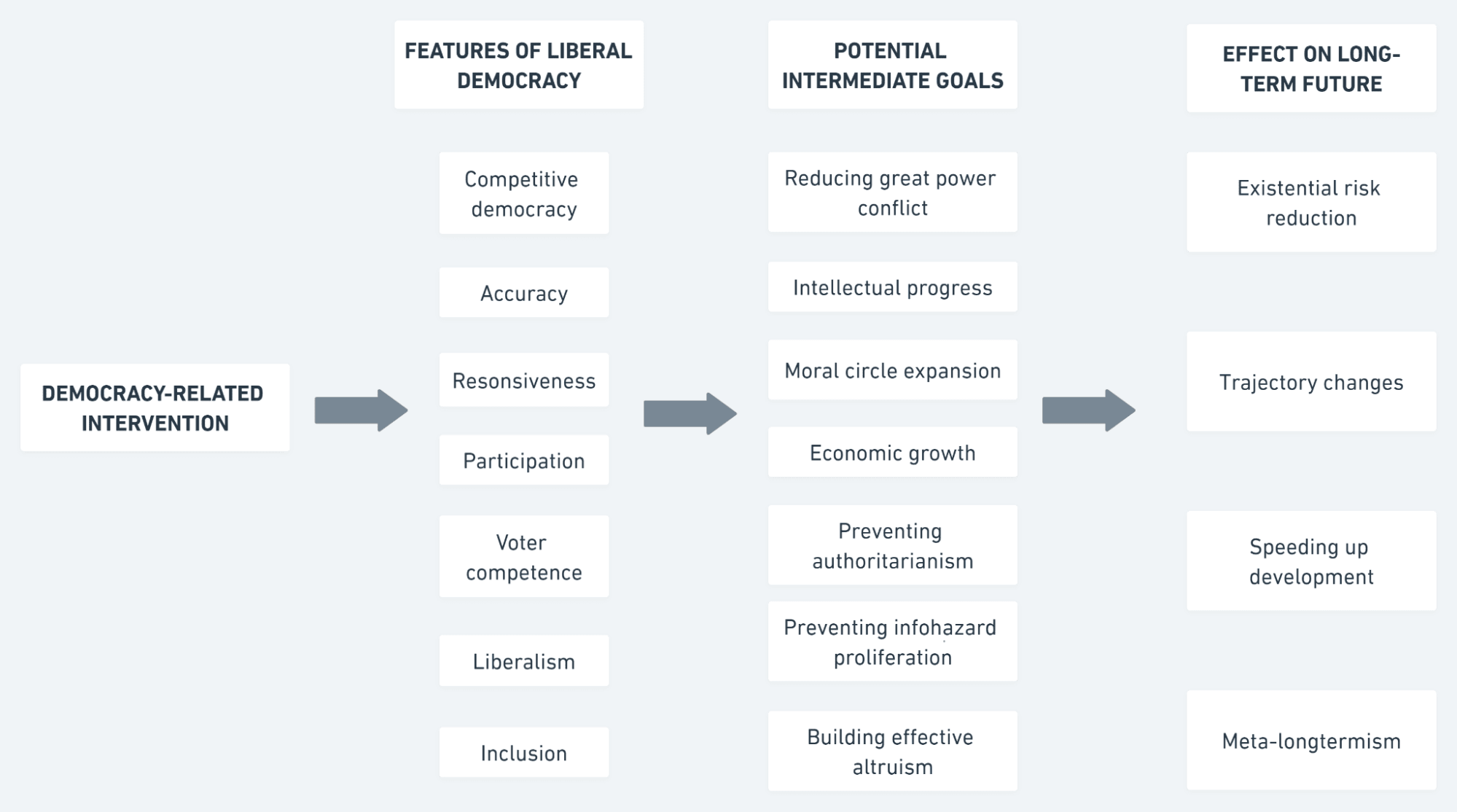

This post attempts to (1) tease apart different features of liberal democracy and (2) analyse how increasing or decreasing a society’s level of each feature would affect various potential intermediate goals for longtermists. By potential intermediate goals, we mean goals we could pursue to potentially increase the expected value of the far future, via four broad categories: existential risk reduction, trajectory changes, speeding up development, or “meta-longtermism” (Greaves and MacAskill, 2021)[1].

This is intended as a step towards a general framework for evaluating:

- how high longtermists should want societies to be on each feature of liberal democracy

- the positive or negative long-term effects of specific democracy-related interventions

- the extent to which longtermists should in general prioritise causes or interventions related to liberal democracy

We also provide some initial thoughts on these points, and outline some directions for further research.

We hope this post, and possible future work building on this framework, could inform longtermism-inclined people who are interested in potentially researching or funding democracy-related interventions, are making career decisions, or are designing and implementing democracy-related interventions.

Key takeaways

-

The features of liberal democracy we identify in Section 1 are[2]:

- Competitive democracy: There are free, fair, and competitive elections (representative and/or direct) and their results are peacefully implemented.

- Accuracy: Politicians are elected in a way that accurately reflects the preferences of voters.

- Responsiveness: Policy choices reflect the preferences of voters.

- Participation: The public exercises their right to vote and participates in decision-making through avenues other than just voting.

- Voter competence: The public is well-informed and are good decision-makers.

- Liberalism: The power of the government is limited so as to preserve rule of law and individual rights, including minority rights.

- Inclusion: Voting rights and other rights are extended to most or all of the population, and the interests of most or all beings are taken into account in decision-making.

-

In Section 2, we then discuss some ways those features may affect a set of seven potential intermediate goals for longtermists, as well as some positive or negative effects these potential goals may have on the long-term future. We suggest that:

- Boosting most of the seven features of democracy identified may reduce great power conflict (though as with the other effects mentioned here, this is uncertain and depends on the context and details of the intervention). This in turn could potentially reduce existential risk and the risk of negative trajectory changes.

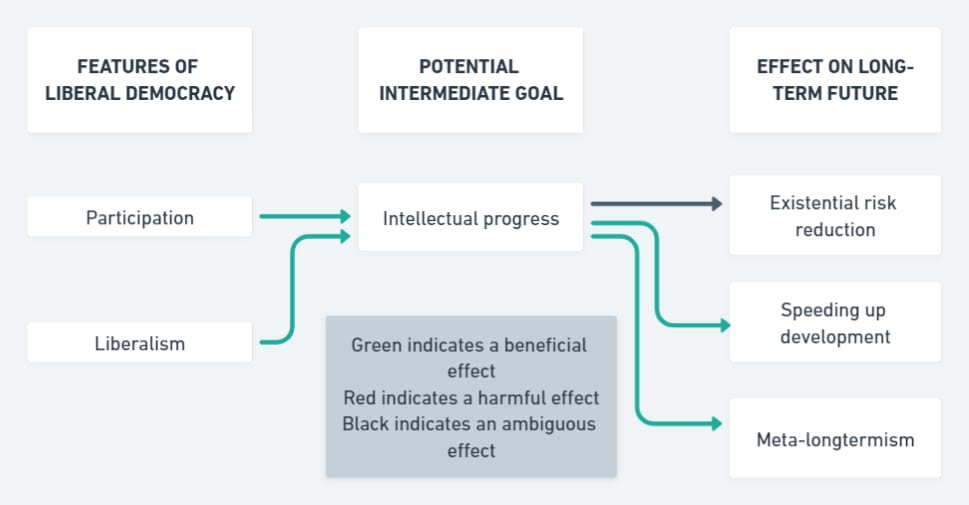

- Increasing participation and liberalism may enhance intellectual progress, which could reduce existential risk (provided there is differential progress), speed up development, and help improve meta-longtermism.

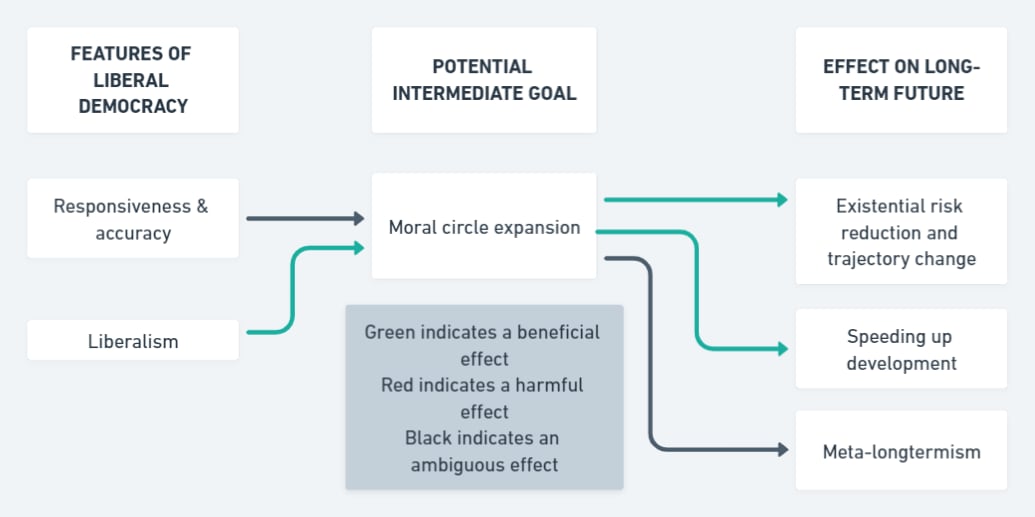

- Higher responsiveness & accuracy, liberalism and voter competence could speed up moral circle expansion, which in turn could make some existential risks less likely, speed up moral progress, and affect meta-longtermism.

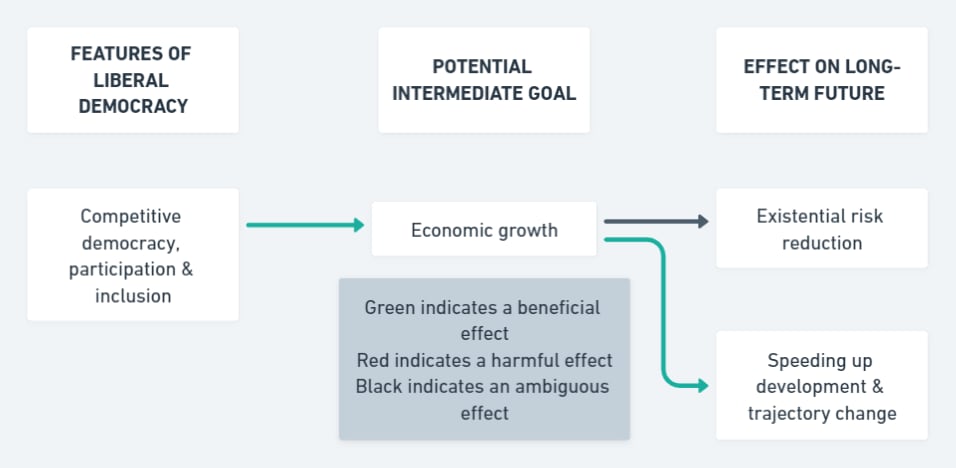

- Greater inclusion & participation in a competitive democracy could cause economic growth, which would impact existential risk and speed up development.

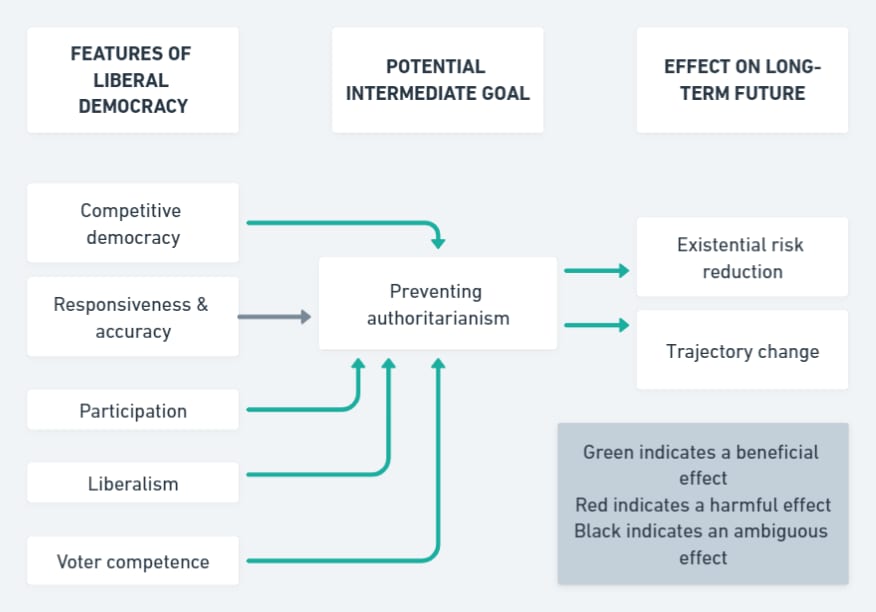

- Improving most features of liberal democracy may help to prevent authoritarianism, which would help to reduce existential risk and other negative trajectory changes.

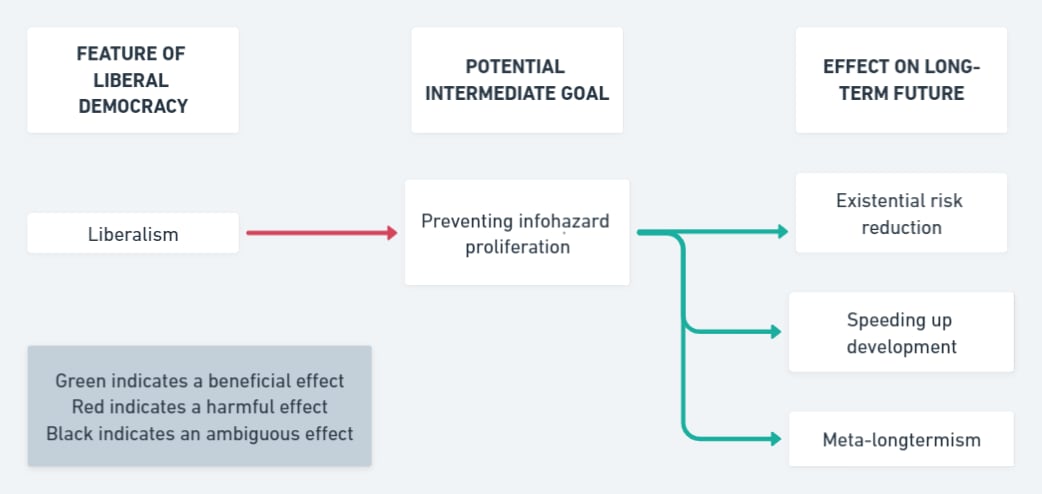

- Increasing liberalism could increase the proliferation of infohazards, potentially increasing existential risks as well as slowing development and hampering meta-longtermism.

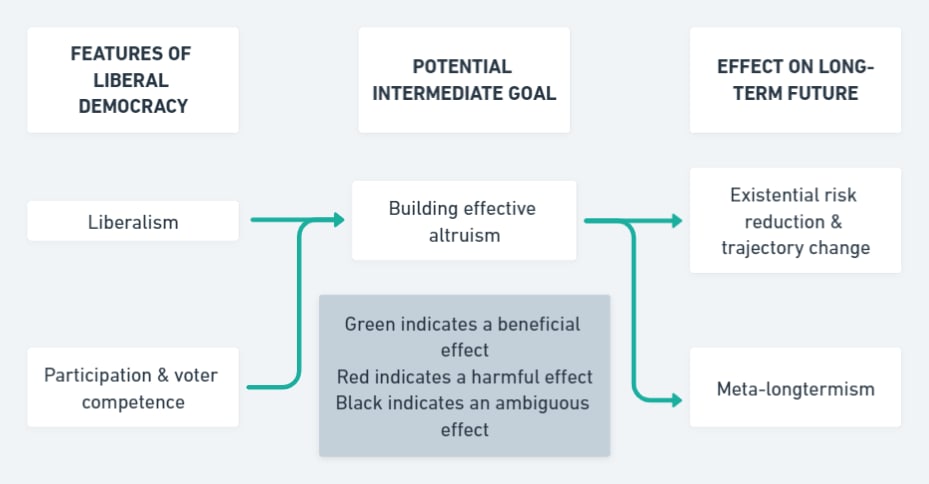

- Higher rates of participation and voter competence, along with liberalism, could help to build effective altruism, which could have spillover effects for existential risk reduction and meta-longtermism.

-

In Section 3, we discuss some possible implications of Sections 1 and 2, including:

- We tentatively think that it is good for the long-term future if (a) voter competence is as high as possible and (b) all other features of liberal democracy are relatively high, though not as high as possible (between 5 and 9 out of 10).

- Given the varied long-term effects of increasing different features of democracy, it may make sense to view safeguarding/promoting/improving liberal democracy as a cluster of cause areas rather than a single cause area; on the other hand, the different features might be highly interconnected.

- Apparent disagreements between proponents of safeguarding/promoting liberal democracy and some proponents of having somewhat “less democracy” may primarily be disagreements about the value of increasing/decreasing competitive democracy and responsiveness; both “camps” might agree more on the value of the other features.

- We should consider whether focusing on promoting the features of democracy is more or less cost-effective than promoting the potential intermediate goals directly or via other indirect means.

-

Section 4 lists further research we’d be excited to see, including research on the importance, neglectedness, and tractability of promoting each feature, how interventions could be tweaked to avoid the downsides of promoting some features; and alternatives/additions to the framework proposed in this post.

The following diagram illustrates the overall (preliminary) framework developed in this post:

Epistemic status

This was our first EA research project, and was deliberately designed as a short (~3 calendar week) “starter project” as part of our Rethink Priorities internship. We’re pretty sure we’ll have gotten some things wrong and also missed some important things. For instance:

- there are likely many other useful ways to break down the elements of liberal democracy (see also Appendices A-C)

- there are definitely many relevant potential intermediate goals for longtermists we’ve ignored here

- we don’t thoroughly evaluate the importance, tractability, or neglectedness of efforts to influence any of the features or goals.

But we hope that even our flawed and incomplete analysis and framework can (a) provide some useful insights, especially when combined with other analyses and frameworks, and (b) make it easier for others to develop better analyses and frameworks.

1. Features of Democracy

What we mean by “feature of liberal democracy”

By “features of liberal democracy”, we mean characteristics that are typically thought to be part of what it means to be a liberal democracy. Each feature can be thought of as a point on one end of a spectrum from the most democratic/accurate/responsive etc. society imaginable to some extreme alternative system of government. (Note that these features are not meant as a definition of liberal democracy. Each feature might not be necessary, and the seven features might not be jointly sufficient, to classify a society as a liberal democracy – more thoughts on this in Appendix C.)

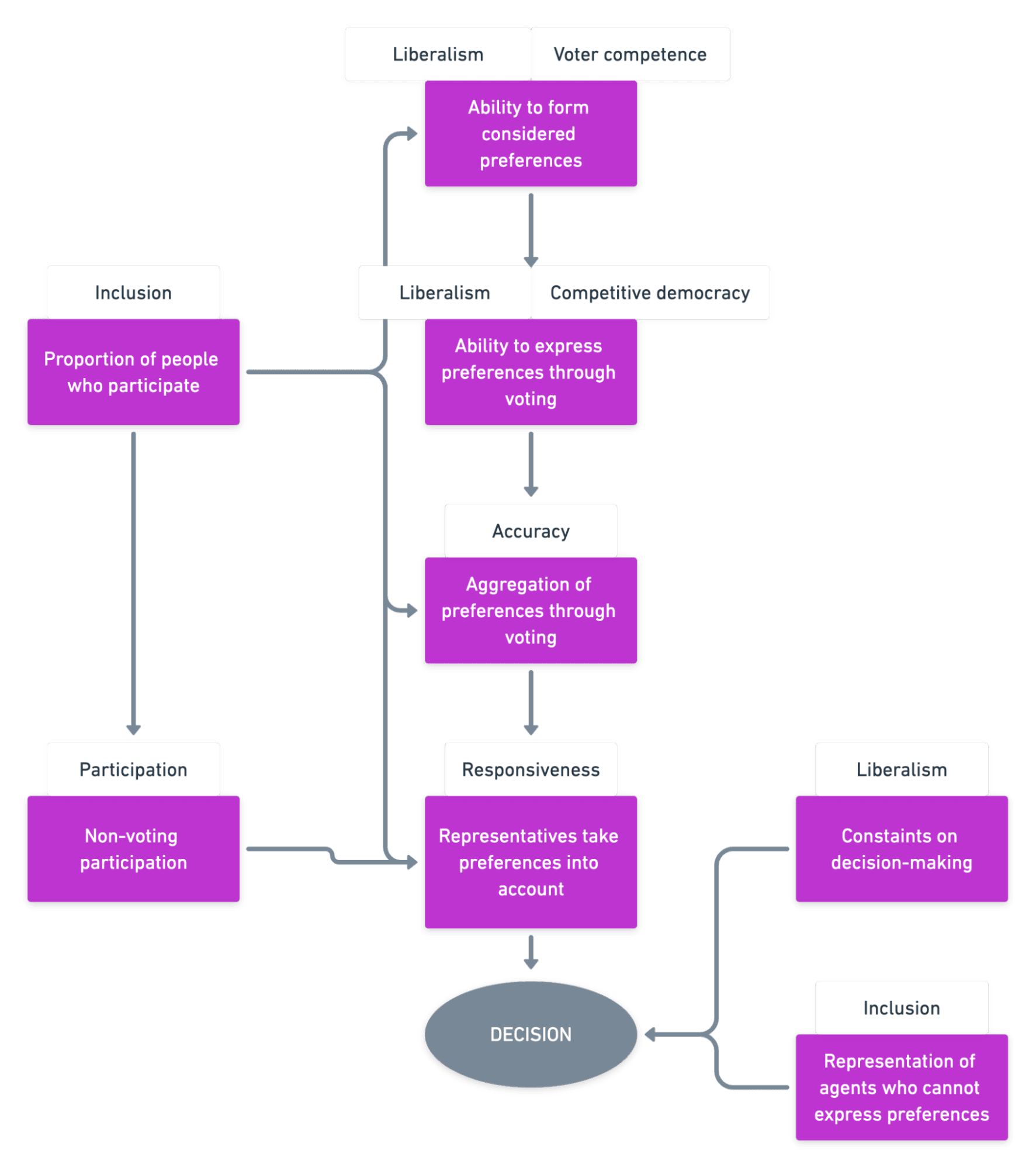

This diagram illustrates the decision-making process of a liberal democracy and how each feature is relevant to this process (inspired by Dahl, 1971)[3]:

We’ve mainly thought about these features from the perspective of national political institutions, rather than in the context of local politics, international institutions, or smaller entities like NGOs, congregations or families. That said, it’s possible that a similar taxonomy would be useful in those cases as well.

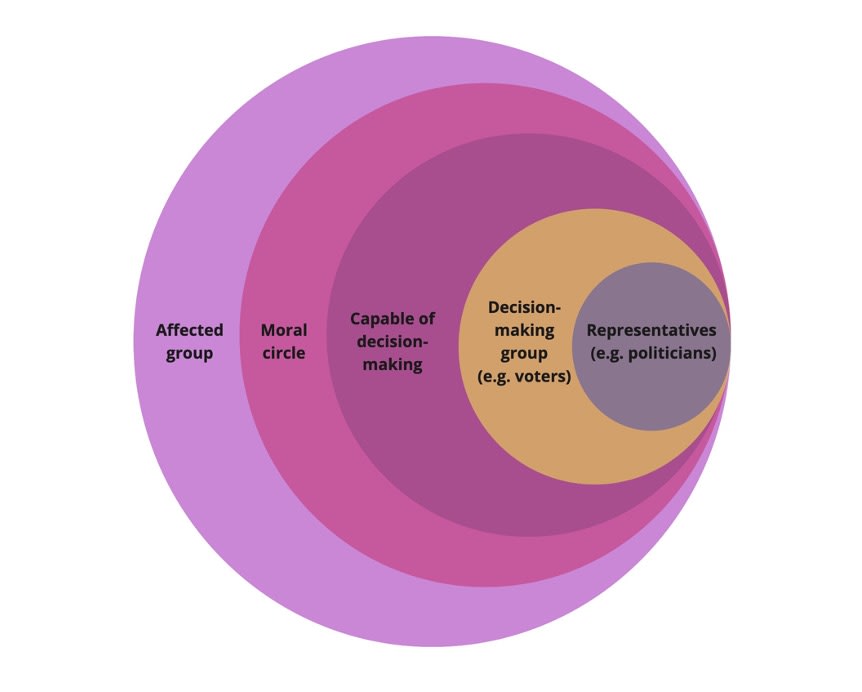

Defining some groups we refer to

To define the features more precisely in the sections below, we will need to refer to the following groups:

-

The representatives: Those elected to formal positions of power by the decision-making group. In a liberal democracy, this will typically be politicians.

-

The decision-making group: Those allowed to participate in the collective decision-making process, for example by electing the representatives or by holding appointed or inherited positions of power (e.g., on a board of technocrats, in the ruling party, or belonging to a group of elites). In a liberal democracy, this will typically be voters.

-

Those capable of group decision-making: Those who are able to participate in group decision-making. Examples of beings that do not belong in this group include future people, animals and very young children. Note that this is the group of beings who are actually capable of participating, not just the group of beings considered capable (e.g., women would be included in this group, even in a society that considers them insufficiently capable of rational thought).

-

The moral circle: Those whose interests are considered relevant for decision-making by the decision-making group. This can come in degrees (e.g., voters might consider national residents 100% part of the moral circle, foreign residents 10% part of the moral circle and non-national non-residents 1% part of the moral; see Aird, 2020). We might imagine a circle of concern where those closest to the centre are those considered fully part of the moral circle.[4]

-

The affected group: Those whose interests are affected by most or all the decisions of the decision-making group. This includes many beings not typically included in the moral circle, for example people in other countries, non-human animals, or future beings.

Here is a diagram illustrating how these groups relate to each other[5]:

1.1 Competitive democracy

What is this feature?

- Definition: There are free, fair, and competitive elections in which members of the decision-making group can vote, and the results of these elections are peacefully implemented. These elections can be representative, direct or both.

- Clarifications:

-

This definition has the counterintuitive implication that a society can have a maximal level of competitive democracy even if only a minority of the population can participate in free and fair elections (e.g., a society where only property-owning white men can vote). However, we do not mean to say that such a society should be classified as a liberal democracy (see Appendix C) or even as democratic in the everyday sense of the word. We separate the features here because we think it can be useful. For example, the separation can make it easier to notice that both may be required for a country to be classified as a liberal democracy, and that, historically, much of democratic thought has been concerned with non-inclusive democracy.[6]

-

Arguably, this cannot be entirely separated from the other features. For example, a degree of liberalism (e.g., free speech and freedom of the press) may be necessary for fair competition between different sides in an election.

-

- What low levels of democracy might look like: Autocracy, aristocracy, anarchy, technocracy, epistocracy, futarchy, competitive authoritarianism.

Components

- Free, fairly counted elections (direct, representative, or both).

- One person, one vote.

- Several viable options in elections (e.g., several candidates or parties).

- Fair competition between different sides in an election (e.g., it is not the case that the incumbent has a high degree of control of the media).

- Peaceful transition of power: The results of elections are implemented peacefully.

- Democratic norms amongst the decision-making group and the representatives (e.g., support for democracy).

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing these interventions or organisations[7]):

- Supporting the development of democratic institutions in countries that currently have autocratic or hybrid regimes, e.g., through conditional aid.

- Supporting unstable democratic institutions against coups, military takeovers or electoral unrest, e.g., through international monitoring of elections.

- Combatting voter suppression, e.g., the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Preventing fraud or interference such as cyberattacks, e.g., Verified Voting (campaign to implement paper ballots) (Hillebrandt, 2020).

1.2 Accuracy

What is this feature?

- Definition: The mechanism for selecting representatives (e.g., electing a president, distributing seats in parliament) accurately reflects the preferences of the decision-making group.

- Clarifications:

- Note that election outcomes are distinct from policy choices (e.g., which economic policies are adopted); the alignment of policy outcomes with decision-making groups’ preferences is addressed in “1.3 Responsiveness”.

- Whereas competitive democracy is about whether there are free, fair elections, accuracy is about how good those elections are at translating votes into election outcomes. Note that accuracy presupposes competitive democracy (i.e., free, fair, competitive elections whose results are peacefully implemented). Hence, though coups or election fraud do in theory lead to a less “accurate” choice of representatives, we would classify them as failures of competitive democracy rather than as failures of accuracy.

- There is little consensus in political science as to what makes a voting system “accurate”. We will not try to settle this debate here, but will instead list some illustrative criteria for what accuracy might mean (but which we do not necessarily endorse):

- The Condorcet criterion: If a candidate would beat all other candidates in a pairwise comparison, that candidate wins the election.

- Social utility efficiency (sometimes called “minimising Bayesian regret” or “voter satisfaction efficiency''): The higher the chance of selecting the candidate(s) that maximise(s) voter utility, the more accurate the voting system.

- Minimising tactical voting: The lower the chance that an individual votes in a way that does not reflect their true preference in order to prevent a certain outcome, the more accurate the voting system.

- Minimising wasted votes: The lower the percentage of votes that do not help elect a candidate, the more accurate the voting system.

- Fair share: Seats are proportional to the number of votes cast for a party or candidate.

- For more examples of possible criteria, see for example Centre for Election Science (2021).

- What low levels of accuracy might look like: Gerrymandering, single-member districts, plurality voting[8], high randomness (i.e., random factors have a large influence on which representatives are elected).

Components

- The voting method has desirable properties, such as the Condorcet criterion, social utility efficiency, and minimising tactical voting.

- The mechanism for distributing seats based on votes in elections of multiple candidates (e.g., parliamentary elections) has desirable properties, such as minimising wasted votes and the “fair share” criterion.

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing these interventions or organisations):

- Voting reform, e.g., the work of the Centre for Election Science (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Preventing gerrymandering, e.g., through redistricting (Hillebrandt, 2020).

1.3 Responsiveness

What is this feature?

- Definition: Policy choices are reflective of the preferences of the decision-making group.

- Clarifications:

- Note that policy choices are distinct from election outcomes; the latter relates to “1.2 Accuracy”.

- There are several situations in which political scientists disagree about which of two systems is more responsive. I will not try to settle these debates here, but will briefly raise some issues that might affect how we define “responsiveness”:

- Responsiveness to preferences regarding means vs. ends: Someone may prefer inconsistent means and ends; if so, policies cannot be responsive to both. For example, assume that immigration increases wages in the manufacturing industry, but many individual believes that immirgration decreass those wages. That individual might simultaneously prefer policies that increase wages in the manufacturing sector (end) and prefer stricter immigration control (means). In this situation, it is unclear whether a responsive society would be one implementing looser or stricter immigration control.

- Responsiveness to the preference of the majority vs. as many preferences as possible: Majoritarian systems like the UK are mainly concerned with responsiveness to majority opinion, while consensus democracies like Denmark place greater emphasis on responsiveness to minority interests.

- The degree of responsiveness towards different population groups should plausibly depend on the degree to which that group is affected (i.e., we might want to be more responsive towards the preferences of the beings most affected by a policy).

- Note that responsiveness may be in tension with liberalism, for example in situations where all or the majority of voters want to limit rights or reduce checks and balances on the government. In such circumstances, a liberal democracy cannot be both maximally responsive and maximally liberal.

- Societies with greater levels of competitive democracy are not necessarily more responsive. For example, it could be the case that a board of technocrats (e.g., an independent central bank overseeing monetary policy) is more responsive than politicians (e.g., if politicians have little incentive to follow public opinion in this particular domain). This is especially true for responsiveness with respect to ends, since technocrats might plausibly be better than politicians at determining which policies best achieve a certain end.

- What low levels of responsiveness might look like: Procedural democracy, oligarchy, high regulatory capture, direct elite influence on policy (i.e., through connections to policy-makers rather than through convincing the public).

Components

- Incentives or norms for representatives to implement policies preferred by the decision-making group.

- Policy is not strongly influenced by elite interests (e.g., the interests of those with greater financial assets, special connections or higher education).

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing or recommending these interventions or organisations):

- Campaign finance reform.

- Research into the likely effects of technocratic or algorithm-based forms of government, e.g., futarchy, epistocracy.

1.4 Participation

What is this feature?

- Definition: The decision-making group participates in voting and can and does participate in decision-making in other ways.

- What low levels of participation might look like: Apathy.

Components

- Opportunities to influence government policy other than elections (e.g., protests, ballot initiatives, citizen's assemblies, political advocacy organisations).

- Actual participation in democracy, as opposed to the mere opportunity to participate (e.g., voter turnout); this is closely tied to the democratic norms mentioned in Section 1.1.

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing or recommending these interventions or organisations):

- Initiatives to increase voter turnout, e.g., vote.org (who provides online information about voting) (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Increasing the number of institutions that allow ballot initiatives (see also Schukraft, 2020).

- Citizen’s assemblies.

1.5 Voter competence

What is this feature?

- Definition: The decision-making group is well-informed and uses good individual decision-making procedures.

- Clarifications:

- Voter competence presupposes the existence of voters; hence, it presupposes some degree of competitive democracy.

- While voter competence is closely tied to the general level of education, rationality, and information access of the population, we focus here on the competencies specifically relevant to making good voting decisions.

- What low levels of voter competence might look like: An un- or misinformed public, polarisation on topics where there is scientific consensus.

Components

- Voters have knowledge relevant to making good voting decisions, e.g., knowledge of the standpoints and track record of the candidates, understanding of economics and social science, understanding of arguments for and against different policies.

- Epistemic norms of public debate and decision-making quality of individual citizens, e.g., degree of truth-seeking vs. tribalistic attitudes, trust in high-quality sources.

**Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing or recommending these interventions or organisations):

- Funding the Discourse Quality Index (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Funding high-quality journalism and information sources, e.g., Our World In Data or GapMinder (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Combatting online propaganda, e.g., funding the Oxford Internet Institute, First Draft, Who Targets Me, Automated Fact Checking (Hillebrandt, 2020).

1.6 Liberalism

What is this feature?

- Definition: There is rule of law and individual rights and freedoms for the decision-making group, which limit the power of the government.

- Clarifications:

- Liberalism both protects citizens against government despotism and protects minorities from tyranny of the majority. As such, for a society to high high levels of liberalism, it must be the case that liberal rights and freedoms are in place even if the majority of the population are in favour of violating them (for example, even if a majority ethnicity is in favour of removing legal protections for a minority group, the government would not be able to do so).

- The liberalism presented here is a relatively thin notion of liberalism, close (though not identical to) the concept of political liberalism. As such, it does not include things such as a liberal market economy or anti-paternalism.

- As was the case of competitive democracy, our definition of liberalism has the counterintuitive implication that a society can have a maximal level of liberalism even if it does not grant liberal rights to the majority of the population (e.g., a society with liberal rights for property-owning white men, but there is little legal protection for other groups and a slave economy). However, we do not mean to say that such a society should be classified as a liberal democracy (see Appendix C), or even liberal in the everyday sense of the word.

- What low levels of liberalism might look like: Parliamentary sovereignty, tyranny of the majority, authoritarian democracy, totalitarianism.

Components

- Rule of law: Transparent laws, equality under the law, de facto law enforcement and access to legal remedy.

- Checks and balances: There are institutions in place to restrain the power of governments, e.g., separation of powers.

- Constitutional limits on government power to preserve civil rights, including freedom of conscience, religion, speech and assembly, and right to privacy.

- Minority rights.

- Pluralism: Toleration of many different opinions and ways of life.

- Liberal norms amongst the decision-making group (e.g., voters) and the representatives (e.g., support for liberalism).

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing these interventions or organisations):

- Preventing or prosecuting government corruption.

- Prosecuting human rights violations, e.g., via funding Amnesty International.

- Investigative journalism, e.g., the Global Investigative Journalism network (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Protecting freedom of press, e.g., The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (Hillebrandt, 2020).

1.7 Inclusion

What is this feature?

- Inclusion has two parts:

- (1) Most or all beings who are capable of participating in group decision-making and are affected by policy decisions are allowed to participate in group-decision-making (i.e., most or all beings which are in both the decision-capable group and affected group are also in the decision-making group).

- (2) The interests of most or all of the beings who are affected by policy decisions are taken into account during those decisions (i.e., the moral circle includes most or all of the affected group).

- Clarifications:

- Inclusion can be specified with respect to any of the features, e.g., inclusion with respect to competitive democracy might be high (if there is universal suffrage) in the same society/institution where inclusion with respect to responsiveness is low (if the opinions of one group are systematically ignored when making actual policy decisions)[6:1].

- A maximally inclusive society would be one in which the following conditions are met:

- The decision-making group (e.g., voters) contains all beings who are both in the moral circle and are capable of decision-making

- The moral circle includes everyone in the affected group.

- This has the implication that a maximally inclusive society would give voting rights and liberal rights to, for example, people in other countries, under-18s, felons and others who don’t currently have such rights in most liberal democracies.

- What low levels of inclusion might look like: Aristocracy, limited franchise, no representation of non-voting beings.

Components

- Proportion of the population that has voting rights, liberal rights, etc., and absence of barriers to those rights being upheld in practice.

- Representation for the interests of non-voting beings (e.g., through lobbying/interest groups, councils, official positions such as ministers, or just individual voters taking those beings’ interests into account)

Illustrative interventions related to this feature

(Note that we are not necessarily endorsing these interventions or organisations):

- Widening the franchise, e.g., to 16-year-olds, felons, or non-citizen residents.

- Protecting minority voting rights, e.g., preventing gerrymandering through redistricting (Hillebrandt, 2020).

- Institutional reforms to represent future generations (see e.g., John & MacAskill, 2020).

- Interventions related to moral circle expansion.

2. Potential intermediate goals for longtermists

This section covers ways in which each of seven potential intermediate goals may:

- affect the long-term future

- be affected by changes in a society’s level of the features of liberal democracy as discussed above.

A potential intermediate goal for longtermists is a goal we could pursue to potentially increase the value of the far future. Fulfilling a goal is not obviously of positive expected value; indeed, some intermediate goals may be ambiguous or negative for the far future. We cache out the costs and benefits of pursuing each goal into four broad categories: existential risk reduction, trajectory change, speeding up development and meta-longtermism[1:1]..

The potential intermediate goals we identify are:

- Reducing great power conflict

- Intellectual progress

- Moral circle expansion (MCE)

- Economic growth

- Preventing authoritarianism

- Preventing infohazard proliferation

- Building effective altruism

We chose these particular intermediate goals because they seemed (a) plausibly substantially affectable by some democracy-related interventions and (b) relatively clearly relevant to the long-term future. But the choice was somewhat arbitrary and partly for illustrative purposes; there are also other goals that meet those two criteria, and these seven are not necessarily the most important for evaluating a given democracy-related intervention. We elaborate on this in Section 4 (Directions for further research). Finally, we focus only on how features of democracy affect potential intermediate end goals. However, in reality there are likely bidirectional relationships and feedback loops, with some intermediate goals impacting particular features of democracy.

2.1 Reducing great power conflict

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Reducing the probability of conflict between major powers - e.g., China and the USA.

What are some ways great power conflict might affect the long-term future?

Existential risk reduction and trajectory change: Great power conflict is often seen as an existential risk factor. That is, it increases the probability of existential catastrophes indirectly rather than directly. This operates through multiple mechanisms - for instance, great power conflict might increase the probability of an AI arms race, make nuclear war more likely, or make global co-operation on various existential risks harder[9]. Thus, reducing the likelihood of great power conflict could reduce existential risk. Additionally, conflict between great powers could alter the global hegemony, changing humanity's long-run trajectory. Whether this is positive or negative depends on the particular trajectory change.

What are some ways democracy might affect great power conflict?

Democracies have historically engaged in war less often than non-democracies. This may be mere correlation (e.g., it may be confounded by GDP). But proponents of democratic peace theory argue that the correlation is in fact causal. Below, we briefly overview some possible, speculative ways in which various features of liberal democracy might indeed reduce the likelihood of war.

Competitive democracy, responsiveness, participation and accuracy: Leaders in countries high in these features must follow the demands of voters more closely, in order to be re-elected. That increases the influence of public opinion on policy decisions, such as in decisions on conflict. Therefore, if voters are more averse to war than leaders are, increasing competitive democracy, responsiveness, participation, and accuracy would, all else equal, make war (including great power conflict) less likely. Conversely, if voters are more inclined towards war than leaders are, increasing these features would, all else being equal, make war more likely. Whilst we tentatively believe that voters are more aversive to war than leaders are, there are likely also other causal mechanisms taking place[10]. Thus, we only weakly suggest that increasing these features is positive for reducing great power conflict.

Liberalism: Democratic peace theory and liberal peace theory are used somewhat interchangeably. Perhaps what really makes democracies less likely to go to war is their liberal nature, rather than anything about voting in particular. Specifically, norms around resolving differences through deliberation, pluralism, and a respect for alternative viewpoints may prevent disagreement escalating to violence. Such norms could ultimately make war and great power conflict less likely.

Inclusion: Countries low in inclusion will likely focus primarily on their own country's citizens (the decision-making group) before others (the wider affected group). This would increase nationalistic sentiment. In contrast, highly inclusive societies are likely to be more conducive to a cosmopolitan mindset. Nationalistic countries would also be more likely to go to war with other countries, compared to cosmopolitan societies. Thus, increasing inclusion will probably decrease the chance of great power conflict.

2.2 Intellectual progress

What is this potential intermediate goal?

For our purposes, intellectual progress includes (but isn’t limited to) technological advancement, scientific progress, progress in philosophy and the social sciences, and increases in general levels of education and reasoning ability. “Progress” is meant as a value-neutral term; some advancements could do more harm than good.

What are some ways intellectual progress might affect the long-term future?

Speeding up development: If new discoveries in science, technology and ideas are made quicker, it allows humanity to reach a better state faster than it otherwise would.

Existential risk (and trajectory changes): There is a need for differential progress, whereby intellectual progress in risk-reducing factors (e.g., wisdom) ought to come before risk-increasing factors (e.g., knowledge of bioweapon construction). Otherwise, faster intellectual progress could increase existential risk.

Meta-longtermism: A better educated population focused on doing impactful/useful work will be more capable of making progress on other longtermist areas.

Crucially, intellectual progress may either increase or decrease existential risk, depending on the particular form of progress being made. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether such progress is all-things-considered good or bad. Further research is required to delineate specifically which forms of progress are good or bad for the long term.

What are some ways democracy might affect intellectual progress?

Participation: Anti-democratic regimes may see new ideas as a threat to their authority, which would incentivise them to restrict the discovery and proliferation of new ideas. To do this, they may seek to exclude or eliminate intellectuals[11]. Additionally, some countries may make it harder for educated/intellectual groups to participate in decision making (e.g., by shrinking the influence of academics on policy). Thus, democracies low in participation could create less intellectual progress.

Liberalism: Some illiberal countries may try to make challenges to authority hard. For example, they may seek to restrict freedom of speech or association. Making it harder to challenge authority could make it harder to challenge conventional wisdom, potentially stymying intellectual progress, especially on topics outside the Overton window.

2.3 Moral circle expansion (MCE)[12]

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Widening the scope of beings considered to be moral patients. One could frame this along two axes: pushing the frontier of the circle outwards (e.g., exploring the moral importance of digital sentience), and increasing the number of people with wide moral circles (e.g., convincing more people to care about non-human animals).

What are some ways moral circle expansion might affect the long-term future?

Existential risk and trajectory change: MCE may reduce s-risks and risks of unrecoverable dystopias, for example by making it less likely that we spread suffering wild animals out into the galaxy.

Speeding up development: Conversely, MCE may simply increase how fast moral progress happens, rather than affecting whether or not it eventually happens[13].

Meta-longtermism: MCE may cause better moral reflection, which can improve future research into longtermist prioritisation and interventions. However, this assumes that the MCE in question is “correct”- that moral circles would be expanding to include entities that should be treated as moral patients, giving them appropriate weight (or a moral anti-realist equivalent of this). However, there can also be “incorrect” MCE. Possible examples could include people coming to believe that forests, stars, or a type of insect that turns out to not be conscious has interests and that respecting those interests is intrinsically morally valuable. “Incorrect” MCE could therefore harm the long-term future for reasons analogous to why “correct” MCE could benefit the long-term future.

What are some ways democracy might affect moral circle expansion?

Responsiveness & accuracy: The extent to which increasing these features improves moral circle expansion depends on the preferences of voters. For example, if voters have wider moral circles than their leaders, then higher responsiveness/accuracy will imply more moral circle expansion. Conversely, if voters have narrower moral circles, then adjusting the political system to accommodate for this preference would have a negative effect on MCE. Thus it is ambiguous whether increased responsiveness or accuracy is net-positive for MCE.

Liberalism: Greater liberalism can help to increase moral circle expansion, for similar reasons to intellectual progress. For example, greater free speech could allow a widening of the Overton window, increasing discussion of more neglected areas like wild animal suffering or digital sentience. This could ultimately widen people’s moral circles.

Voter competence: Better informed voters are more likely to engage in a more “correct” form of MCE, caring about the correct moral patients. Conversely, societies low in voter competence may push MCE in the wrong direction, caring about entities which do not have intrinsic moral value. Thus, higher voter competence could help to avoid the issue outlined under meta-longtermism.

2.4 Economic Growth

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Increasing GDP, that is “the (market) value of goods and services”.

What are some ways economic growth might affect the long-term future?

Speeding up development and trajectory change: Increasing both GDP and the rate it grows could have persistently good effects on the long-term future. For more, see Bostrom’s (2003) astronomical waste argument and Cowen’s (2018) argument that economic growth should be a moral imperative (conditional on existential security).

Existential risk reduction: There is debate about whether economic growth increases or decreases existential risk. On the one hand, increased growth increases the pace of development of new and potentially dangerous technologies (e.g., AI, nanotech, biotech), giving us less time to prepare. On the other hand, increased growth allows for more spending on safety and protection from these technologies, which allows humanity to better control them. Further resources on these topics can be found under economic growth or differential progress on the EA wiki. For a deeper analysis, see Aschenbrenner (2020).

What are some ways democracy might affect economic growth?

Competitive democracy, participation, and inclusion: Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) argue that inclusive institutions cause faster growth, compared to extractive institutions. They define inclusiveness as involving the widest group of people in political and economic life, whilst extractive institutions only benefit a small elite. This overlaps with our concepts of competitive democracy, participation, and inclusion. Thus, if their hypothesis is true, then increasing those three factors may increase GDP growth. For instance, interventions to remove voting restrictions could help to engage more citizens in the political process, which could increase economic growth. However, Acemoglu and Robinson’s conclusions are disputed (Gates, 2013).

2.5 Preventing Authoritarianism

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Preventing the risk of societies coming under the control of a single group/leader, who hold exclusive political power. At its extreme, this could include totalitarianism. Taking preventative measures to stop democratic backsliding may help to prevent authoritarianism.

What are some ways authoritarianism might affect the long-term future?

Existential risk reduction: Malevolent actors (Althaus and Baumann, 2020) who become authoritarian leaders may potentially inflict astronomical levels of suffering, perhaps locking humanity into an undesired or enforced dystopia, and potentially leading humanity into a fate worse than mere extinction. An alternative existential risk may be that authoritarian leaders are less competent at dealing with other x-risks, such as the development of new technology. Thus authoritarianism may increase existential risk indirectly. A further worry is that humanity may never achieve its full potential - for instance, a stable authoritarian leader could prevent space colonization from occurring, leaving vast amounts of the galaxy without value. This would also constitute an existential risk via a failed continuation.

Trajectory change: A less extreme worry may be that authoritarian leaders fail to address certain sources of disvalue, even if humanity still enjoys a flourishing future. For example, they may not prevent wild animal suffering on Earth even if most of the universe is filled with value.

What are some ways democracy might affect authoritarianism?

Competitive democracy: Efforts to improve competitive democracy make it easier to remove leaders from power in elections, which can reduce the risk of authoritarianism arising.

Responsiveness & accuracy: The extent to which increasing these features makes authoritarianism more or less likely depends on the preferences of voters. For example, if voters tend to prefer non-authoritarian leaders, then increasing how well the political system responds and reflects voters’ preferences makes authoritarianism less likely. Conversely, if voters prefer more authoritarian leaders, then adjusting the political system to accommodate for this makes higher responsiveness/accuracy more likely to bring about authoritarianism. It seems likely that, on average, most democratic citizens would prefer less rather than more authoritarianism in their political system (however, this is very context-dependent).

Participation: Countries with high levels of participation seem more likely and better able to challenge an authoritarian leader, compared to where apathy is high or participation is curtailed. Additionally, because authoritarian regimes may try to limit participation, means of keeping participation high once an authoritarian first gains power could be an especially important way to prevent authoritarianism from being locked in.

Liberalism: Authoritarianism and liberalism are almost polar opposites – societies high in liberalism are far less likely to see an authoritarian rise to power. For example, because liberalism safeguards pluralism, multiple value systems and beliefs are allowed to co-exist, whereas authoritarian regimes tend to exclude values that deviate from orthodoxy.

Voter competence: Democracies with low levels of well-informed voters may be more susceptible to polarisation and populism, which can in turn be a driver of electing authoritarian leaders. Thus, efforts to increase voter competence may reduce the likelihood of authoritarianism.

2.6 Preventing infohazard proliferation

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Reducing the probability of infohazards - that is, risks arising from the spread of (true) information. For example, spreading knowledge of how to use a dangerous technology.

What are some ways infohazards might affect the long-term future?

Existential risk (and trajectory change): Information getting into the hands of certain agents increases the risk they inflict serious damage upon humanity. For example, there is a risk if malevolent actors (terrorists, rogue states, misanthropic people) learn how to develop and deploy advanced biological weapons. Even if agents do not wish to cause such outcomes, as the number of agents with knowledge of a dangerous technology increases, the chance that disaster occurs increases.

Speeding up development and meta-longtermism: Fear of many infohazards could motivate restrictions on topics available for research. This could slow down progress and meta-longtermism work.

What are some ways democracy might affect infohazards?

Liberalism: Free speech could potentially increase the chance of infohazards, both by allowing scientists/policymakers to discover new dangerous ideas, and for these ideas to be easily communicated amongst the general public. Restrictions on free speech and the media could help to slow the spread of risky information in wider society. Additionally, demands for freedom of information could backfire, by increasing infohazard proliferation[14].

2.7 Building effective altruism

What is this potential intermediate goal?

Interventions which aim to grow, shape, or otherwise improve effective altruism as an intellectual community.

What are some ways building effective altruism might affect the long-term future?

Meta-longtermism: The EA community has developed key ideas related to longtermism. It seems reasonable to assume that further EA movement building would benefit global priorities research and cause prioritisation, and that the shrinking or collapse of the EA community would hinder global priorities research and cause prioritisation, since these are particular niches unique to the EA community.

Existential risk reduction & trajectory change: The EA community is particularly invested in groups working to reduce existential risk, and (to a lesser extent) making non-existential risk trajectory changes. Thus, it seems reasonable that the loss of the EA community would counterfactually reduce the expected value of humanity via these means.

What are some ways democracy might affect building effective altruism?

The EA community has grown out of and so far been most prominent in Western English-speaking democracies. There may be key features about these societies and their democratic systems to explain why the movement took off there and not elsewhere. Below we list a couple of suggestions for why this could be the case.

Liberalism: Protections on the right to free speech, right to assembly & intellectual exploration have made it easier for the EA community to emerge and develop. Contrast this with countries with high censorship, repression of political opponents and little intellectual freedom (such as China), where it would have been much harder for the community to start from.

Participation & voter competence: Societies where participation is high may have more citizens concerned about social issues. Additionally, countries with high voter competence may favour reasoning and evidence over ideology and partisanship to generate policy solutions. Increasing these features may thus help to grow the set of people who could become involved in the effective altruism community.

3. Possible implications

3.1 What level of each feature of liberal democracy should longtermists want society to have?

What would the ideal political system from the point of view of longtermism look like, in terms of its level of the seven features of liberal democracy? This section gives some tentative guesses informed by our above analysis, using a scale from 1-10 for each feature. But note that:

- This would of course in practice be highly context-dependent. For example:

- Perhaps the lower a society’s levels of voter competence and inclusion and the “worse” its preferences (e.g., if the public favours moves towards authoritarianism or war), the lower we might want its levels of competitive democracy, accuracy, responsiveness, and participation to be.

- And how “good” a society’s voter competence and preferences are will likely vary between different topic areas, such that the ideal level of competitive democracy, accuracy, responsiveness, and participation may also vary between topic areas.

- This is not an evaluation of the “importance” of efforts to promote each of these features, nor how much we should prioritise promoting each of these features.[15]

Competitive democracy: 7/10

- High levels of competitive democracy may typically decrease the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism.

- High levels may increase economic growth.

- High levels may help to prevent authoritarianism.

- All of these effects are highly sensitive to the alternative in question (and unusually so, since the possible alternatives to competitive democracy are significantly more varied than for most of the other dimensions).

- For example, a system such as a technocracy might decrease the risk of great power conflict and increase economic growth more than a democracy, whereas the opposite seems to be true for a system such as an autocracy.

- Hence, what level of competitive democracy is ideal depends on what alternative we are considering or think is most likely.

Accuracy: 8/10

- More accuracy may typically decrease the risk of great power conflict.

- More accuracy may typically decrease the risk of authoritarianism.

- If voters have a preference for war or more authoritarian leaders, then this will not be true. Nevertheless, on average it seems that the preferences of voters are against rather than in favour of war/authoritarianism, compared to their leaders.

- An additional reason is that one possible alternative to accuracy is a system with a bias in favour of those already in power, which may be conducive to a move towards authoritarianism.

- More accuracy may have an ambiguous effect on moral circle expansion.

- Once again, this depends on the preferences of voters relative to their leaders – if voters favour more MCE, then more accuracy would typically increase MCE.

- Besides the potential effect on authoritarianism, a main reason to prefer less accuracy is that there may be other incidental harms from a high-accuracy voting system. A voting system might have other features than accuracy, such as a centrism-bias, favouring a certain political party, increasing stability, etc. If those features are more prevalent in less accurate voting systems and we think those features have positive effects, we might prefer less accurate voting systems.

Responsiveness: 6/10

- More responsiveness may typically decrease the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism.

- More responsiveness appears to have an ambiguous effect on moral circle expansion

- The optimal level of responsiveness is highly contingent on voter competence, how “good” voters’ preferences are, and the topic area in question (as noted earlier), as well as on how we define responsiveness (see discussion in Section 1.3; for example, responsiveness with respect to ends may be more desirable than responsiveness with respect to means).

Participation: 8/10

- More participation may typically decrease the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism.

- More participation may typically increase intellectual progress.

- More participation may typically increase economic growth.

- More participation may help to build effective altruism.

Voter competence: 10/10

- More voter competence may typically decrease the risk of authoritarianism.

- More voter competence may typically help moral circle expansion.

- More voter competence may typically help to build effective altruism.

- The main reason that the score for voter competence is so high is that:

- It may increase the chance that the first four features decrease the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism, as noted above.

- It seems correlated with the general competence, education levels and decision-making ability of members of a society. These all seem likely to have positive effects on the long-run future through mechanisms other than improving democracy.

- It is difficult to think of ways in which high voter competence might make democracy worse for the long-run future.

Liberalism: 8/10

- More liberalism may typically decrease the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism (we have especially high confidence in the latter effect).

- More liberalism may increase EA movement growth and seems likely to increase intellectual progress and moral circle expansion.

- But more liberalism may increase the risk of infohazards.

- More liberalism can be in tension with competitive democracy and responsiveness, so could have negative effects in cases where those things would have positive effects.

- May increase existential risk directly by making it more difficult to identify and prosecute individuals and groups that may pose an existential risk (see e.g., Bostrom, 2019).

Inclusion: 9/10

- More inclusion may increase economic growth.

- More inclusion may decrease the risk of great power conflict.

- The optimal level of inclusion is contingent on:

- The entities we are considering including (bearing in mind that some entities aren't moral patients, but could be included in moral circles anyway).

- Potentially the feature with respect to which we are considering inclusion (e.g., we might want greater inclusion for liberalism than for responsiveness).

- The main reason that the score for inclusion is so high is that inclusion in most cases seems to strengthen the other effects mentioned.

- For example, if liberalism promotes intellectual progress by enabling more diverse ideas to be discussed and spread, this effect is only stronger if more people are allowed to participate in this process.

3.2 Between-cause and within-cause prioritisation

Further work along the lines of this post could provide clearer answers on (1) how much to prioritise the area of safeguarding/promoting/improving liberal democracy relative to other cause areas and (2) what to prioritise within this cause area. For now, we will merely note a few high-level points relevant to those questions.

- The long-term future effects of different features of liberal democracy, or the effects of features in different contexts, may vary substantially. This may push in favour of seeing this as a cluster of cause areas, rather than a single cause area, or we could focus on how valuable individual goals or interventions are within this cause area.

- On the other hand, many interventions target multiple features at once, and increasing (or preserving or decreasing) one feature could sometimes increase (or preserve or decrease) others. For example, it is plausible to us that liberalism is much less likely to sustain over time in the absence of competitive democracy and responsiveness.

- As discussed in Sections 2 and 3.1, for most or all features, increasing that feature seems likely to have a bad effect on some potential intermediate goal or in some context. We should account for these downside risks when engaging in between- and within-cause prioritisation, and should also consider adjusting the precise design and application of a given intervention in this area so as to reduce downside risk (e.g., promoting liberalism may inadvertently make it easier to spread infohazards).

- Some seeming disagreements between various people (in or outside of people EA) discussing democracy might involve less or a different kind of disagreement than it might appear. For example, proponents of “safeguarding/promoting/improving liberal democracy” might appear to be in disagreement with proponents of “less democracy” (e.g., people who are convinced by the arguments in books like 10% Less Democracy (Jones, 2020), Against Democracy (Brennan, 2016) and The Myth of the Rational Voter (Caplan, 2008)). But there might be less disagreement that it appears at first, because:

- The latter people typically argue that specifically competitive democracy and responsiveness have certain negative consequences; this isn’t necessarily an argument against the other features of liberal democracy.

- Additionally, as noted in Section 3.1, the value of competitive democracy and responsiveness are highly contingent on the alternative competitive democracy is being compared to and the definition of responsiveness. Different sides in a debate might be comparing to different alternatives or using different definitions.

- Hence, there might be no disagreement, or there might be a disagreement “only” about whether less competitive democracy and responsiveness on the margin would be good or about which alternative to a current system is most likely.

- Rather than through improving features of liberal democracy, we could also target the potential intermediate goals more directly (e.g., via work explicitly focused on preventing great power conflict or on building effective altruism) or via other indirect pathways. So, as with all things, we should consider whether focusing on these features of liberal democracy is more effective than focusing on something else.

- One reason this focus might be good is that it seems plausible that (some of) these features allow for an unusually strong combination of (a) shovel-ready, scalable interventions to affect these variables, and (b) these variables having a nontrivially positive expected impact on many intermediate goals.

- On the other hand:

- These features - and the broad area of improving/safeguarding/promoting liberal democracy - seem not very neglected.

- The features seem to often have unclear or probably small effects on the potential intermediate goals, or to have a good effect for one potential intermediate goal but a bad effect for another.

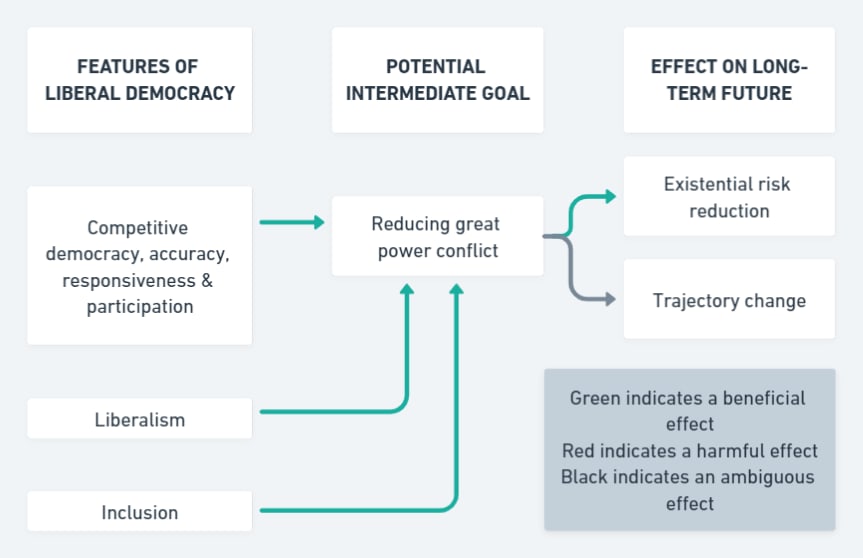

3.3 A simple worked example

In this section, we provide a stylised example of how one might apply the framework in this post to evaluating and prioritising between two democracy-related interventions. Of course, assessing the effects of real-world interventions would be much more complicated; this is merely meant as an illustration.

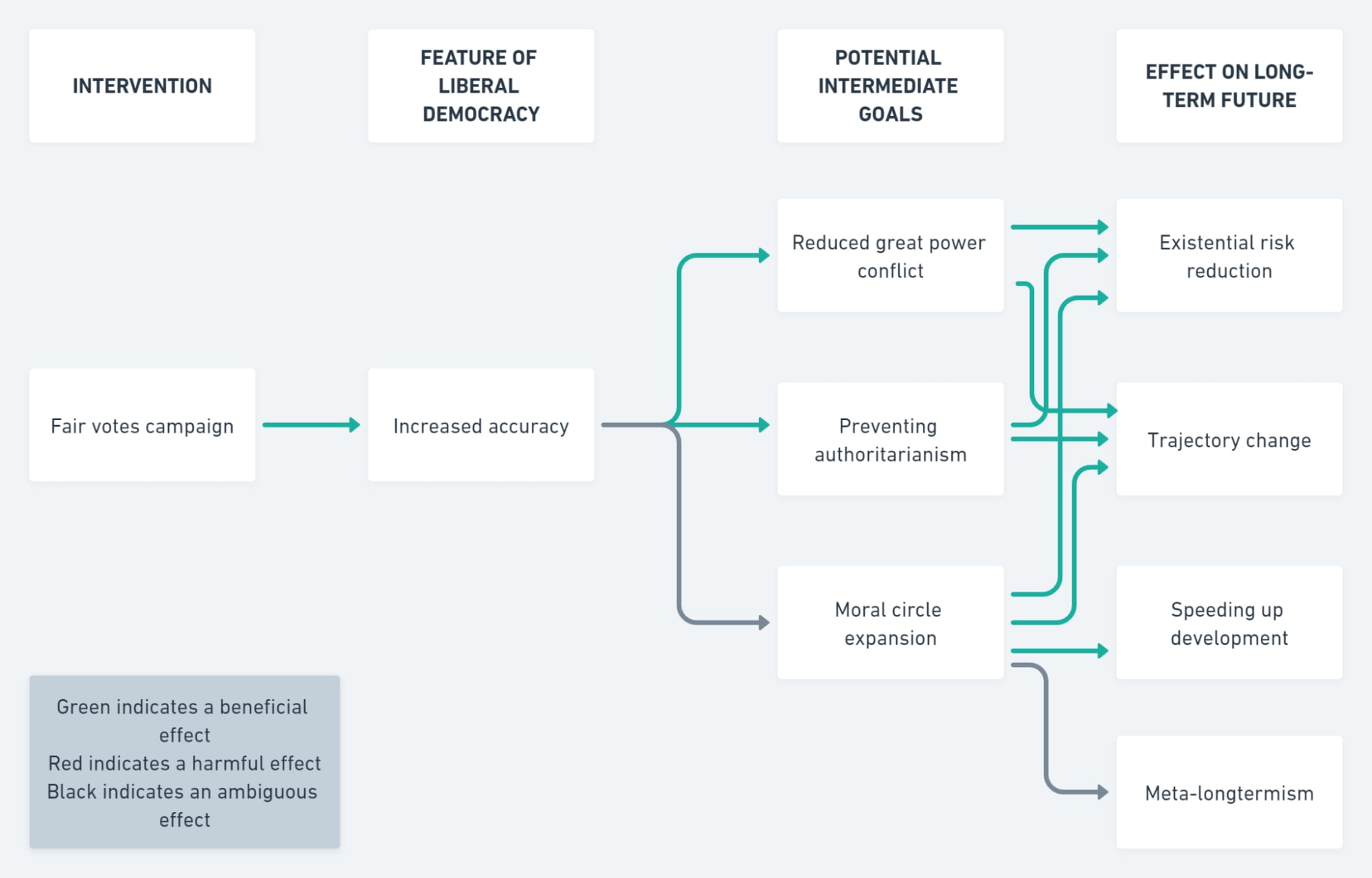

Suppose you can fund either the “Fair votes” campaign group or the “Free people” campaign group.[16] “Fair votes” campaigns for voting reform, which mostly increases accuracy, whilst “Free people” promotes human rights and a free media, which mostly increases liberalism.

Greater accuracy may reduce the risk of great power conflict and authoritarianism. This may in turn reduce existential risk and increase the chance of positive trajectory change. However, it is not clear whether greater accuracy is good for moral circle expansion, nor whether MCE is all-things-considered good for the far future. This is illustrated below:

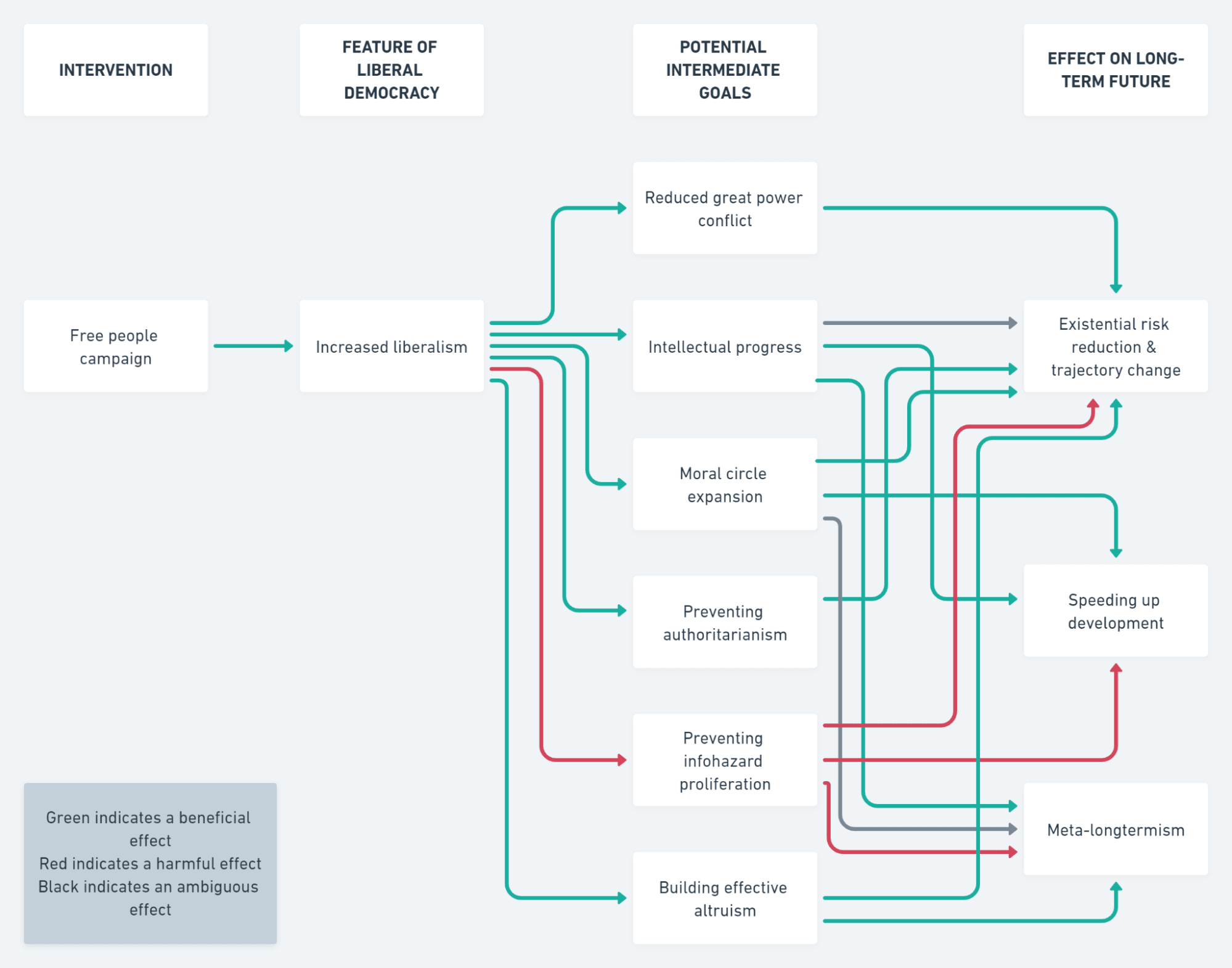

Meanwhile, increased liberalism may reduce great power conflict, increase intellectual progress, increase moral circle expansion, help to prevent authoritarianism, increase infohazard proliferation and improve the EA movement. Each of these intermediate goals may in turn have numerous positive, negative or ambiguous effects on the far future, as illustrated[17]:

This gives an overview of the effects of interventions in question. As next steps (see Section 4), one would need to evaluate the size of these effects, the relative importance of the potential intermediate goals and their effects, and the tractability and neglectedness of the interventions.

4. Directions for future research

We’d be excited to see future research in this area, for example:

- Exploring additional potential intermediate goals for longtermists and how particular features of democracy may affect them. Some potential goals that could be explored include:

- Civilizational resilience

- Global public goods provision

- Improving institutional decision making

- Increased or decreased likelihood or stability of a world government.

- Doing importance, neglectedness and tractability analyses of the features or interventions addressing the features. As noted in Section 3.1, this could involve:

- Estimating the importance of promoting different features, which would involve estimating the magnitude and sign of (a) the various long-term effects described in this post, (b) perhaps other long-term effects we failed to mention that flow via the potential intermediate goals discussed in this post, and (c) long-term effects that flow via potential intermediate goals we didn’t discuss in this post.

- Estimating the neglectedness and tractability of promoting different features, which is not done in this post.

- For those designing or implementing democracy-related interventions, finding ways to mitigate the downsides of promoting each feature. For example, designers of liberalism-related interventions could think of ways to decrease the risk of information hazards as a result of their intervention.

- Expanding on the links between the features and potential intermediate goals, especially ones with low-confidence or ambiguous effects.

- Proposing alternative frameworks for evaluating democracy-related interventions and seeing how they compare to this one.

Acknowledgements

This research is a project of Rethink Priorities. It was written as a collaboration between Marie Buhl and Tom Barnes. Sections 1, 3.1, and 3.2 were mainly written by Marie and Section 2 and 3.3 were mainly written by Tom, with all other parts written jointly.

The basic idea for this post originated in a conversation between Michael Aird, Linch Zhang, Peter Wildeford and Marcus Davis. We’re grateful to them for providing us with the idea and extensive notes.

Special thanks to Michael Aird for tirelessly supporting us with many fast, long and useful comments. Thanks to Charles Dillon, David Mathers, David Moss, Hauke Hillebrandt, Konrad Seifert, Marcus Davis, Miranda Zhang, Neil Dullaghan and Peter Wildeford for reviewing our drafts and providing helpful feedback.

If you like our work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can see more of our work here.

Appendices

Appendix A: How did we come up with the features and intermediate goals?

To make a long list of potential features of liberal democracy, we used various background sources that explicitly or implicitly suggested different features a liberal democracy might have. The background sources (in order of importance) were (a) notes from staff at Rethink Priorities, (b) writings by EA-aligned organisations/people on democracy, (c) Wikipedia pages on different forms of government and (d) political science papers on how to define democracy.

We selected which features to include based on which of them seemed constitutive of liberal democracy, conceptually distinct, and plausibly distinct in their effects on the long-term future.

As mentioned in Section 2, we chose these particular intermediate goals because they seemed (a) plausibly substantially affectable by some democracy-related interventions and (b) relatively clearly relevant to the long-term future. But the choice was somewhat arbitrary and partly for illustrative purposes; there are also other goals that meet those two criteria, and these seven are not necessarily the most important for evaluating a given democracy-related intervention. We’d be excited to see others think of more potential intermediate goals and how they link to the features (see Section 4).

Appendix B: Other features of institutions

Institutions can also vary on many other features we didn’t include in this post, mainly because we didn’t intuitively think these features are part of what it means to be a liberal democracy. But this is of course arguable, and these other features might be relevant for evaluating institutions even if they’re not features of liberal democracy. For this reason, we decided to list some of these features here:

- Government competency: The ability of a government to achieve its stated goals.

- Federalism: The degree to which power is decentralised and geographical regions have political sovereignty.

- Economic equality: The degree of economic equality between citizens and the degree to which everyone’s basic needs are met.

- Bureaucracy: The degree to which governments follow strict rules and procedures vs. making decisions on an ad hoc basis.

(One could of course think of many other such features.)

Appendix C: Relation between the features and a definition of liberal democracy

Various ways of defining liberal democracy imply that some of the seven features focused on in our post aren’t necessary for a country/institution/society to be a liberal democracy, or that these features aren’t collectively sufficient.

No liberal democracy (in theory or in practice) scores 10/10 on all these features (since some of them are sometimes in tension with one another, as noted in Section 1.1 and 1.). Having these features to a maximal degree also isn’t necessary to be considered a liberal democracy.

That said, our personal view at this time is that:

- Some degree of competitive democracy, liberalism, inclusion and responsiveness are necessary to be considered a liberal democracy.

- Accuracy, participation and voter competence are mainly features that make a country more liberal democratic and tend to make liberal democracy better for its constituents, rather than features necessary to being a liberal democracy at all.

Just as liberal democracy is composed of several features, alternative systems (e.g., authoritarianism) typically differ from liberal democracy in several respects.

Bibliography

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty.

Aird, M. (2020). Moral circles: Degrees, dimensions, visuals. Effective Altruism Forum, July 24.

Althaus, D. & Baumann, T. (2020). Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors. Effective Altruism Forum, April 29.

Anthis, J. R., & Paez, E. (2021). Moral circle expansion: A promising strategy to impact the far future. Futures, 130, 102756, June.

Aschenbrenner, L. (2020). Existential risk and growth. Global Priorities Institute, September.

Bostrom, N. (2019). The Vulnerable World Hypothesis. Global Policy Volume, 10, 4, November.

Brennan, J. (2016). Against democracy. Princeton University Press.

Caplan, B. (2008). The Myth of the Rational Voter. Princeton University Press.

Centre for Election Science. (2021). Electoral System Glossary. The Centre for Election Science.

Christiano, T. (2021). Democracy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. Yale University Press.

Gates, B. (2013). Good ideas, but missing analysis. GatesNotes, February 26.

Greaves, H., & MacAskill, W. (2021). The case for strong longtermism. Global Priorities Institute, June.

Hillebrand, H. (2020). Decreasing populism and improving democracy, evidence-based policy, and rationality. Effective Altruism Forum, July 27.

Jones, G. (2020). 10% less democracy. Stanford University Press.

Koehler, A. (2020). Problem areas beyond 80,000 Hours’ current priorities. Effective Altruism Forum, June 22.

Schukraft, J. (2020). Intervention Profile: Ballot Initiatives. Effective Altruism Forum, January 13.

Notes

In section 4.4 of “The Case for Strong Longtermism”, Greaves and MacAskill discuss “Uncertainty and “meta” options” as a means to improving the far future. This involves increasing our capacity to research and implement longtermist interventions, for example via global priorities research ↩︎ ↩︎

Note that some political scientists also use some of these terms to mean things different to what we mean by them here. ↩︎

Dahl specifies the following necessary (but not sufficient) condition for democracy: “All full citizens must have unimpaired opportunities:

- To formulate their preferences

- To signify their preferences to their fellow citizens and the government by individual and collective action

- To have their preferences weighed equally in the conduct of the government, that is, weighted with no discrimination because of the content or source of the preference.” (Dahl, 1971, p. 2)

Other definitions of democracy (see Christiano, 2021) also characterise it as a method of group decision-making between equals. This inspired the diagram, which intends to show how the features we identify relate to various stages of democratic group decision-making. ↩︎

By “moral circle” we mean “the group whose interests are considered relevant when making policy decisions”. This is slightly different from conventional EA uses of the term, which refer to which entities one considers morally relevant in general, not just when making one type of decision (e.g., policy decisions). For example, someone could believe that the interests of people in other countries should be considered when making philanthropic decisions but not when making political decisions; for that person, people in other countries are included in the moral circle in the traditional sense, but not in the sense we describe here. ↩︎

A few caveats:

- Some groups could be fully overlapping rather than partially overlapping, e.g., “capable of decision-making” and “decision-making”, “moral circle” and “affected group” (see “1.7 Inclusion”).

- In theory, all groups shown as being fully inside the affected group might only be partially inside the affected group, since it is possible that people who are not affected by decisions are nonetheless taken into account, have decision-making power etc.

Another way to view the “Inclusion” dimension is as a separate axis of the six other dimensions. On this view, each of the first six dimensions run along two axes: the degree to which the dimension applies to some people (the decision-making group), and the number of people to which it applies (the size of the decision-making group). On this view, the society described here would have a high degree of competitive democracy on the first axis, but a low degree of competitive democracy on the second axis. ↩︎ ↩︎

We list interventions largely for illustrative purposes. We expect many of the interventions we mention would not be cost-effective, and that some may even do more harm than good, at least from a longtermist perspective. See Section 3.1 for some initial thoughts on how high we should want societies to be on each feature of liberal democracy and what this implies for intervention priorities. ↩︎

Single-member districts and plurality voting can be considered inaccurate for example because, compared to alternatives like proportional representation, they tend to involve more tactical voting, more wasted votes, more violations of the “fair share” criterion and possibly less social utility efficiency. ↩︎

On the other hand, one could argue that conflict between great powers could at times reduce existential risk - for example, democracies could take preventative measures to prevent authoritarian lock-in ↩︎

For example, leaders may be incentivised to start wars if they believe they will receive an electoral boost from this ↩︎

For example, see the persecution of intellectuals in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union ↩︎

Note that this section uses the standard definition of “moral circles”, rather than focusing on moral circles with respect to policy decisions as we did in Section 1. ↩︎

See Anthis & Paez, 2012, footnote 6 on the distinction between changing the speed and the end state of MCE. ↩︎

Note: In the diagram, liberalism is bad at stopping the spread of infohazards, but the prevention of infohazard spread is beneficial for the long-term future ↩︎

Importance assessments (in the sense of importance, neglectedness and tractability) would need to take into account how bad diversions from the optimal level of a feature would be – this is probably different for different features and for different sizes of diversions. Prioritising between promoting different features (and between promoting liberal democracy and other cause areas) would require further considerations of the tractability and neglectedness of promoting different features. ↩︎

These groups are entirely fictitious. Assume both are equally funding constrained. ↩︎

For simplicity, we have combined existential risk reduction with trajectory changes. In this example, the colour of the arrows was the same for both, so this made no difference ↩︎

So I remain unconvinced that there's a specific longtermist case for democracy, but I think there is a longtermist case for some kind of context in which longtermist work can happen.

What I have in mind is I'm not sure democracy or liberal democracy is necessary to work on longtermist cause areas, but liberal democracy is creating an environment in which this work can get done. So there's an interesting question, then: what are the feature of liberal democracy that enable longtermist work?

I ask this because I'm not sure that, for example, democracy is necessary to work on improving the longterm future, however it's also clear that something about liberal democracy has allowed people to start doing work towards bettering the longterm future, so it must have some features we care about for that purpose. Maybe it is the case that electing the government is the key feature that matters, but I don't see an obvious causal chain there between the two, which makes me wonder what the features are that do matter that we'd want to ensure are preserved if we want people to be able to work on making the longterm future better, even if it means having a government that is not what we'd consider to be democratic.

Maybe another way to put my comment is that this post feels like it's taking for granted that liberal democracy is good for longtermism so we want to figure out what it is about liberal democracy that makes it good, but I'd say it slightly differently: longtermism has been fostered within liberal democracies, so this means there must be something about liberal democracies that matters, but this doesn't imply that longtermism requires liberal democracy, so we should cast a wider net and look at features of specific liberal democracies where longtermist work is flourishing without presupposing that it's somehow connected to the system of government (for example, maybe it's just that liberal democracies are rich and have lots of extra money to spend on "hobby" interests like longtermism, and any sufficiently rich society, no matter the government, would be able to foster longtermism; I don't know, but that's the kind of question that seems to me worth exploring).

Thanks for raising these points! A few of my (personal) reactions:

1. We definitely didn't intend for the post to presuppose that democracy is good for the long term. It’s true that most of the potential effects we identity are positive-leaning – but none of these effects, nor the all-things-considered effect, is a settled case.

2. I think the question of what conditions allowed EA to come into existence is interesting, although not sure if that's the main positive impact of liberal democracy (especially given we don’t have super strong evidence that liberal democracy was necessary for EA to arise). As is sort-of mentioned in the post, (inclusive) liberalism might be the feature most directly important to the flourishing of EA. But of course it’s hard to tell and I think it’s plausible that a combination of features reinforcing each other is key.

I think this is really cool and a great way of breaking things down - thanks for writing this up!

This is a good first exploration into the relationship between liberal democracy and longtermism. Since I care about both liberal democracy and the long-term future, I'm glad to see this.

Regarding what you term "liberalism", a more specific term for this would be "civil and political rights" or "civil liberties." You identify two ways in which civil liberties can lead to increased existential risk: infohazards and impeding effective policing. Yet existing liberal democracies already deal with these tradeoffs in a way that can be considered compatible with liberal rights:

Given how liberal democracies already navigate these tradeoffs involving civil liberties, I think it's more useful to talk about specific changes to civil liberties (e.g. making it illegal to distribute genetic code for harmful viruses) than blanket statements about "increasing or decreasing liberalism" as a whole. Having narrow limitations on what speech can be shared while strongly protecting freedom of expression in general, and taking a similar approach with privacy, would give us the benefits of these civil liberties while limiting them in situations where they could be harmful.

By the way, the subheading "Illustrative interventions related to this feature" under the section "1.5 Voter competence" isn't formatted as a subheading.