David_Althaus

Posts 9

Comments112

I'm mostly warning about complacency about liberals being safe from error

I can certainly agree with that. :)

I don't really understand why liberalism is getting the prefix "classical" here though.

Mostly to reduce the chance of misinterpretation. In the US, "liberal" is often used interchangeably with something like "leftist", "Democrat", or "progressive", and I wanted to make clear that I don't want any of these connotations. I also wanted to emphasize the core principles of liberalism, and avoid getting bogged down in specific policy debates.

Thanks for the comment!

On the No True Scotsman concern

Fair point. But I think there's a genuine structural asymmetry here. When liberal democracies commit atrocities, they do so by violating their own safeguards—secrecy, executive overreach, circumventing checks and balances. The CIA's Cold War operations required hiding what they were doing from Congress and the public, precisely because the actions were incompatible with the system's principles. And liberal democracies contain built-in self-correcting mechanisms: free press, independent courts, elections, public accountability. The US eventually declassified the documents and the atrocities became part of the historical record that we can openly discuss and condemn. This self-correction is a core feature of classical liberalism.

The "not real communism" defense has the opposite problem. Concentrating all power in a vanguard party, suppressing class enemies, and eliminating institutional checks aren't deviations from Marxism-Leninism, they're core features. Once you've done all that, totalitarian horror isn't a failure of implementation but a foreseeable consequence of the design. (Also, the CCP is still putting Mao on all their banknotes.)

"Time-tested" doesn't mean "never fails", it means better outcomes on average, less catastrophic failures, and mechanisms to recognize and correct its own failures. The right question isn't "does liberalism guarantee safety?" (nothing does), it's "which system produces the best outcomes and has the strongest safeguards?" The historical record is pretty clear.

On the Nazis exploiting Weimar democracy

The argument seems to be essentially: "Nazis rose to power in a liberal society, therefore liberalism enabled Nazism." But this arguably confuses background conditions with causation. The Nazis also exploited elections, but most people still seem quite partial to them.

The actual causal story involves the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation, the Great Depression, Weimar's specific constitutional weaknesses, the mutual radicalization spiral between communists and Nazis, and the political establishment's catastrophic miscalculation in thinking they could "control" Hitler. Free speech was a minor ingredient, if that.

The fact that safeguards sometimes fail doesn't mean the safeguards are the problem. Some people die in car crashes even while wearing seatbelts.

The wide classical liberalism bucket

I agree that not all values in the admittedly wide "classical liberal bucket" are equally anti-fanatical. For what it's worth, I'm quite concerned about extreme wealth inequality, partly because it enables potential oligarchs to subvert the very system of liberal democracy. But the core claim is about the procedural principles—separation of powers, rule of law, universal rights, institutional checks—and those seem pretty robustly anti-fanatical to me.

Thanks, I think this narrows the disagreement productively! :)

On the reframed Frankfurt School argument: I strongly agree with the claim that modern societies can retain technical rationality while losing wisdom and ethical reflection (cf. the section "differential intellectual regress").

Where I still disagree is with locating this tension inside Enlightenment reason. The decoupling of technological competence from moral reasoning isn't something Enlightenment values produce. It's what happens when Enlightenment values are abandoned while the technology remains. Nazi Germany didn't gradually narrow Enlightenment reason into instrumental reason; it rejected Enlightenment values from the start and kept the trains running. It seems that the Frankfurt School framing suggests we need to be suspicious of reason itself, while the fanaticism framing suggests we need more reason, more epistemic humility, more willingness to revise beliefs—i.e., more Enlightenment values, not fewer.

On whether the decoupling of technological capacity from wisdom is "accidental or structurally enabled by modern forms of organization": I think the empirical record makes this fairly clear. Barbarism long predates modernity, antiquity and the Middle Ages were full of it. Hunter-gatherers engaged in lots of tribal warfare. In contrast, most modern liberal democracies conduct far fewer wars, have far less poverty, and produce far better outcomes across virtually every metric of human flourishing than any pre-modern society (see footnote 9 on the huge drop in violence rates). So modern institutions are clearly neither necessary nor sufficient for producing barbarism.

What often leads to barbarism is the abandonment of core principles of liberal democracy like separation of powers, universal rights, and the rule of law—especially when ideologically fanatical or malevolent actors are in charge. Modernity gives you better tools, but the tools aren't inherently the problem. That said, I agree that modernity results in great technological capacity which increases the stakes and increases the harm if bad things happen.

On the "productive version" of critical theory as methodological modesty (that reason operates within institutions and incentives that can distort it) I certainly agree with that! But I'd note that many Enlightenment thinkers themselves already understood this perfectly well. Adam Smith, for instance, warned that regulatory proposals from businessmen "ought always to be listened to with great precaution... It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even oppress the public." So you don't necessarily need the Frankfurt School apparatus to get to "institutional incentives distort reasoning."

On Cold War violence, it sounds like we agree! :)

Communism probably also provides intellectual resources that would enable you to condemn most of the many very bad things communists have done, but that doesn't mean that those outcomes aren't relevant to assessing how good an idea communism is in practice.

But much less clearly so than classical liberalism. Communism lacks any clear rejection of violence, provides no robust mechanism for resolving disagreements or conflicts, and doesn't advocate for universal individual rights. Lenin, one of its most influential theorists, explicitly advocated for a "desperate, bloody war of extermination".

So it's no surprise that communism almost always led to disaster and essentially never to a prosperous, flourishing society, in contrast to classical liberalism, which much more rarely led to disaster and much more often to flourishing.

Thanks for flagging this, but you're looking at an unfiltered sample (N=2,980) which includes almost all participants regardless of data quality. All statistics in the main text use a filtered sample (N=1,084), which excludes participants who failed two attention checks, reported not answering honestly, gave invalid birth years, or strongly violated additivity (see the relevant section in the main post, including footnotes 94 and 95 for more details). The unfiltered numbers should be ignored as they clearly contain a lot of inattentive participants. (We will update the supplementary materials to label them clearly, sorry about the confusion).

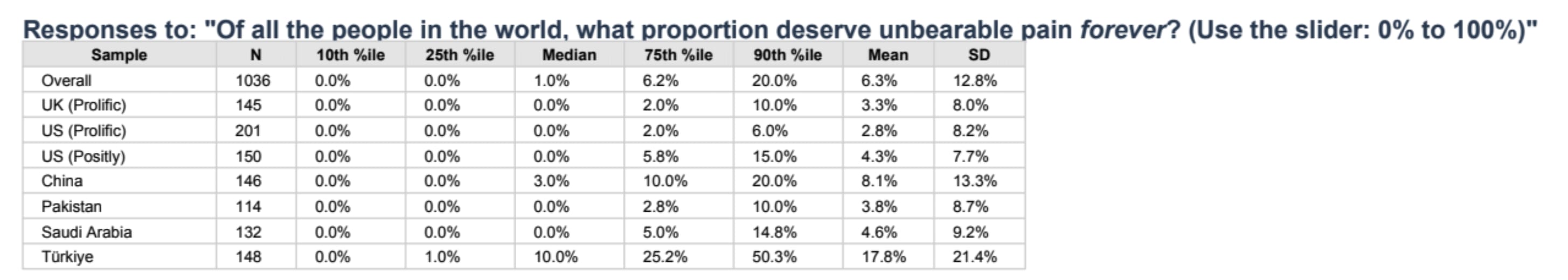

Here is the table that only includes participants who passed our inclusion criteria (the 7th table in the selected stats doc.

As you can see, the numbers are much lower: 25% of Chinese respondents believe that at least 10% of people deserve unbearable pain forever.

(Note: this table shows N=1,036 rather than the N=1,084 in the main text; the small discrepancy likely reflects a stricter additivity filter. I'm confirming with my co-author Clare Harris who analyzed the survey and wrote the supplementary materials.)

I appreciate your thoughtful comment, but I think several of the claims here don't hold up under scrutiny.

Nazism was not a product of Enlightenment rationality

The Frankfurt School's thesis in Dialectic of Enlightenment, that the Holocaust was somehow a product of Enlightenment reason, is one of the most influential yet poorly supported claims in 20th-century social theory. The problem is simply that Nazism was explicitly anti-Enlightenment and anti-rational.

The Nazis rejected virtually every core Enlightenment principle. They replaced reason with Blut und Boden mysticism, the Führerprinzip (the principle that the leader's intuition supersedes all evidence and deliberation), and a racial pseudoscience that bore no meaningful resemblance to the scientific method. They burned books and celebrated instinct, will, and blood over careful reasoning.

The Frankfurt School argument relies on equivocating between two very different meanings of "rationality." Yes, the Nazis used trains, bureaucracy, and industrial logistics efficiently. But efficiently using technology to implement your goals is far broader than the Enlightenment commitment to reason and evidence as guides to truth—and was already done in antiquity. We discuss a closely related issue in the essay under differential intellectual regress: fanatical regimes can maintain or even advance technological capabilities while systematically degrading wisdom, moral reflection, and reason. Scientific and technological progress requires some narrow form of rationality, and can certainly enable you to do much more harm. But that's a point about the power of technology, not about Enlightenment values or classical liberalism.

The Jakarta Method and Cold War interventions

The 1965–66 Indonesian massacres are among the worst atrocities of the 20th century, and it's horrible that the US intelligence community encouraged and supported them.[1] I totally agree that the US bears substantial responsibility for this and other atrocities like the Vietnam War, supporting Pinochet's coup against the democratically elected Allende, arming radical Islamist Mujahideen in Afghanistan (helping enable the Taliban), and orchestrating the 1953 Iranian coup. We briefly mention some of these in the essay (e.g., in the first bullet point here, Appendix F, and the spreadsheet of historical atrocities).

But these atrocities were largely driven by fanatical anti-communism (especially on the US side) that divided the world into an existential struggle between good and evil, dehumanized the enemy, and held that defeating communism was so important that it justified "any means necessary", including supporting malevolent autocrats and mass killings. They represent failures of liberal democracies to live up to their own principles, not evidence that those principles caused the violence. Classical liberalism provides the intellectual resources to condemn the Jakarta killings.

On the critical theory tradition

You suggest that ideology should be understood as something structural and embedded rather than merely a matter of overt zealotry. But this is a false dichotomy. We explicitly mention how fanatical ideologies can become normalized and mainstream (that's partly why we chose the term "fanaticism" over "extremism").

Several of the thinkers you cite exemplify a reflexive skepticism toward liberal universalism that treats all claims to reason, evidence, and universal moral concern as merely disguised exercises of power. This is its own form of epistemic closure. If every appeal to evidence is just "instrumental rationality serving domination," you've constructed an unfalsifiable framework.

Of course, power absolutely shapes knowledge production, and Western intellectual traditions have real blind spots. But there's a crucial difference between "we should be attentive to how power can distort reasoning" (true) and "Enlightenment rationality is always a tool of domination"; an extraordinary claim that, taken seriously, would undermine the very epistemic tools needed to identify and correct injustice, including the injustices you rightly highlighted.

- ^

The Act of Killing, in which some of the perpetrators cheerfully reenact their murders decades later, is one of the most horrifying and interesting documentaries I've ever watched.

Thanks for the comment, Michael.

On wild animal suffering

You raise a good point, and I do think WAS persisting into the long-term future is a serious concern. That said, I think the distinction between incidental and intentional suffering is absolutely crucial from a longtermist perspective.

Agents who value ecosystems or nature aesthetically don't have "create suffering" as a terminal value. The suffering is a byproduct—one they might be open to eliminate if they could do so without destroying what they actually care about. That makes this amenable to Pareto improvements: keep the ecology, remove the suffering. It's at least conceivable that those who value ecosystems would be open to interventions that reduce suffering in nature—though they'd probably dislike doing so via advanced technology like nanobots. (Though they might be open to more "natural" interventions, but more on that in a moment.)

It's also worth noting that WAS at its current Earthly scale isn't an s-risk (by definition s-risks entail vastly more suffering than currently exists on Earth). For it to become one, you'd need agents who actively spread it to other star systems and insist that all the animals keep suffering, and refuse any intervention. At that point, you're arguably describing something that could be called "ecological fanaticism": dogmatic certainty, a simplistic nature-good/intervention-evil dichotomy, and willingness to perpetuate vast suffering in service of that ideology. Admittedly, this is a bit of a definitional stretch but it's at least in the neighborhood.

As an aside, I think it's worth noting that a lot of people already care about reducing wild animal suffering in certain ways. Videos of people rescuing wild animals—dogs from drowning, deer stuck on ice—get millions of views and enthusiastic responses. There seems to be broad latent demand for reducing animal suffering when it's made salient. The vast majority of wild animal suffering persists not because people terminally value it, but because we lack the resources and technology to do much about it right now. That will change with ASI.

What's more, fanatics will resist compromise and moral trade. Someone who likes nature and has a vague preference to keep it untouched, but isn't fanatically locked into this, would presumably allow you to eliminate the suffering if you offered enough resources in return (and you do it in a way that doesn't offend their sensibilities—superintelligent agents might come up with ways of doing that). It's plausible that altruistic agents will own at least some non-trivial fraction of the cosmic endowment and would be happy to spend it on exactly such trades. Fanatical agents, by contrast, won't trade or compromise.

Where I think the concern about fanaticism becomes most acute is with agents who believe that deliberately creating suffering is morally desirable—e.g., extreme retributivist attitudes wanting to inflict extreme eternal torment. If people with such values have access to ASI, the resulting suffering could dwarf WAS by orders of magnitude, especially factoring in intensity. That's the type of scenario we're trying to draw attention to.

On the atrocity table and intentional deaths

I also received a somewhat similar concern via DM: filtering for intentional deaths and then finding fanaticism is circular reasoning. I don't think it is because intentional ≠ ideologically fanatical. You can have intentional mass killing driven by strategic interest, resource extraction, personal megalomania, etc. (And the table does indeed include 2 non-fanatical examples). The finding is that among the worst intentional mass killings, most involved ideological fanaticism. This is a substantive empirical result, not a tautology.

Including famines wouldn't even change the picture that much. You'd add the British colonial famines, the Chinese famine of 1907, and Mao's Great Leap Forward (though the Great Leap Forward was itself clearly driven by fanatical ideological zealotry, and certain ideologies—colonialism, laissez-faire ideology, etc.—probably also substantially contributed to the British famines in India).

More importantly, once you start including famines, why not also include pandemics? And once you include pandemics, why not deaths from disease more generally—cancer, heart disease, etc.? And why not include deaths from aging then? Obviously, the vast majority of deaths since 1800 were not due to fanaticism; most were from hunger, disease, and aging.

But with sufficiently advanced technology, you won't have deaths from disease, hunger, or aging. These deaths don't reveal anything about terminal preferences. Intentional deaths do. That's why, from a longtermist perspective, focusing on intentional deaths isn't cherry-picking, it's studying the thing that actually matters for predicting what the long-term future looks like.

ASI will give agents enormous control over the universe, so the future will be shaped primarily by the terminal values of whoever controls that technology. Unintentional mass death from incompetence or nature (like aging) is terrible, but solvable.

Last, I worry that we're getting too hung up on the atrocity table. Even in a world where ideological fanaticism had resulted in only a few historical atrocities, I'd still be concerned about it as a long-term risk. The table is just one outside-view / historical argument among several for why we should take fanaticism seriously. The core reasons for worrying about fanaticism are mostly discussed in these sections.

I want to point out that the ethical schools of thought that you're (probably) most anti-aligned with (e.g., that certain behaviors and even thoughts are deserving of eternal divine punishment) are also far more prominent in the West, proportionately even more so than the ones you're aligned with.

For what it's worth, we recently ran a cross-cultural survey (n > 1,000 after extensive filtering) on endorsement of eternal extreme punishment, with questions like "If I could create a system that makes deserving people feel unbearable pain forever, I would" and "If hell didn't exist, or if it stopped existing, we should create it [...]".

~16-19% of Chinese respondents consistently endorsed such statements, compared to ~10–14% of US respondents—despite China being majority atheist/agnostic.[1]

Of course, online surveys are notoriously unreliable, especially on such abstract questions. But if these results hold up, concerns about eternal punishment would actually count against a China-dominated future, not in favor of one.

- ^

On individual questions, agreement rates were usually much higher, especially in China and other non-Western countries. The above numbers reflect a conservative conjunctive measure filtering for consistency across multiple questions.

Hi Luke,

Sorry, it seems that we haven't received your email (where did you send it, btw?). As stated on our website, we planned to give around $30m this year (though by now it seems that we may end up closer to $40m). We're currently considering our strategy and the available opportunities and may give substantially more (possibly >$100m/year) in the coming years.

Interesting points!

(I think the US example is perhaps a bit more complicated. It's not just very wealthy, it's also highly unequal and offers much weaker safety nets than most other liberal democracies. So the bitter politics may have more to do with material insecurity than with post-scarcity boredom.)

That said, I do agree that as scarcity recedes, zero-sum status games could become more prevalent.

Another reason why fanaticism could matter more in the long run is that future disagreements may be much more about terminal value differences than instrumental policy questions like how to create jobs or make things more affordable (no one will need jobs and there could be huge abundance). That's where fanaticism becomes especially relevant because it entails potentially drastic value disagreements that are locked in, with potentially no room for change, trade, or compromise.