Key takeaways:

This article aims to estimate the probabilities of any PhD student to get a permanent position (tenure track) in academia, in order to inform career decisions. The findings have been:

- Between 10% and 30% of PhD alumni get a permanent position at academia.

- Often around 70% of PhD alumni want to work in academia.

- My estimate is that conditional on wanting to get a permanent position in academia, you should have a baseline chance between 15-30% of landing a permanent job at academia

The most important factor determining whether you actually get such positions is the number of first-authored articles, although the precise numbers by field are not known in Pure Science or Technological fields. They are nevertheless available in the Biomedical and Sociology fields.

Introduction

Contributing with a career to one important cause is perhaps one of the most effective ways of having a positive impact in the world. However, since EA careers are not so well established, the few opportunities that are available tend to grab all the attention, and less conventional choices, although celebrated, are often difficult to assess and find.

For instance, I aim to contribute to the AI Safety problem. However, it is not clear what is the best way. In my case I see two main options for next steps:

- Academic research.

- Work in an "EA organisation" or opportunity such as those that often appear in the 80000 hours job board.

Some cons of working in academia due to the long time it takes, the low chances of getting tenure, and the perverse incentives to publish a lot no matter how relevant the topic is. On the other hand, working at academia gives a lot of freedom, social status and influence and the possibility of making fields of interest to Effective Altruism (including e.g. AI safety and global priorities research) more respectable. Some other considerations might be found in CS PhD 80000 hours career profile.

However, one factor not analysed in depth in that profile is the probability of getting a tenure position. In this post we aim to get a first estimate that could inform people.

Just to inform the reader, the typical career path in academia usually involves a PhD (~3 years in Europe, 5 in the US which also includes the master), one or two postdocs of 2-3 years each (this step may be longer, up to 7-8 years), and then obtaining access to junior research fellows, which may be promoted to professorship with time. The most difficult part seems to be changing from the temporary postdoctoral positions to the permanent research fellow one.

Approximate academic career path. The lengths are only estimated based on the comments above, actual timelines vary a lot. Junior researcher is the name I give to the first permanent position.

Baseline

In order to establish a baseline, the following might be useful:

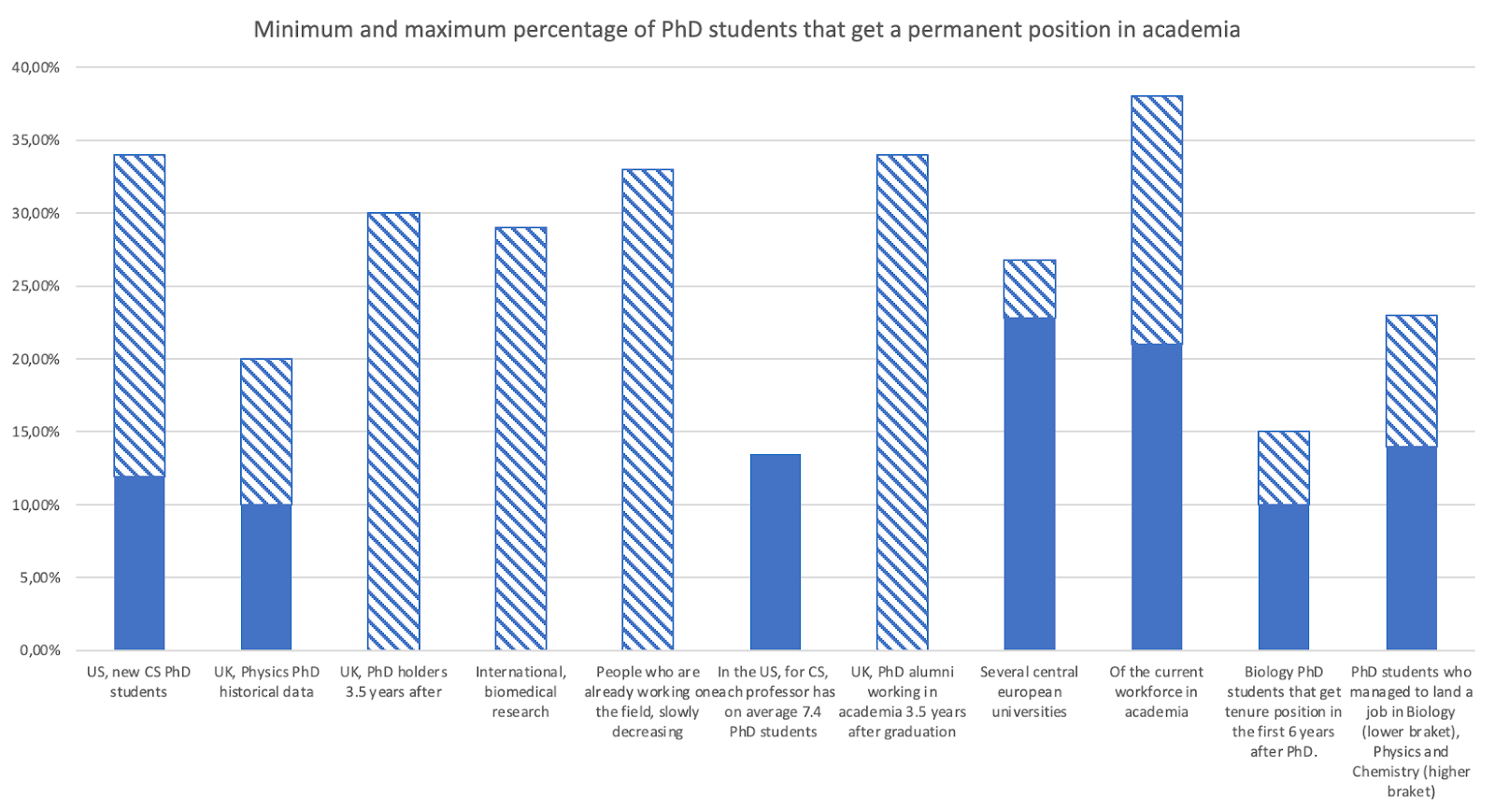

- This CS PhD career outcomes survey indicates in table D4 that around 34% of people ending their PhDs in the US remain in academia, and of those 12% go straight into tenure positions - without ever doing a postdoc.

- This document from IOP shows a graphic with data of career flows. However, I do not assign great credibility since the data is quite hard to track where exactly it comes from, and additionally it reports

"For physicists, that 3.5% figure [the number of people securing a permanent research position] is probably a little low. Slightly older data collected by the Institute of Physics and the US National Science Foundation suggest that the fraction of physics PhD students who obtain permanent academic jobs has historically hovered between 10 and 20%."

and

"Indeed, according to an August 2012 survey carried out by the American Institute of Physics (AIP), nearly half (46%) of new physics PhD students at US institutions want to work in a university." - In the UK, 3.5 years after graduation, around 30% of PhD holders remain in academia, according to this document based on the Long DLHE survey.

- Figures 2 and 3 of this Nature article indicate that 29% of people with a PhD in biomedical sciences end up in academia. Interestingly, since research is more common in industry in the US, tenure track positions seem to be less common compared with non-US research career paths.

"US scholars enter into the for-profit sector in professional job-types conducting applied research at a much higher rate than international scholars. International scholars enter the academic sector in tenure-track job-types conducting basic research at twice the rate of US scholars". - This article from Science indicates that around 20% of the PhD holders in the job market have a tenure position, and it is slowly decreasing. In CS and Mathematics it is a bit higher, it says, 33%.

- In this article, it is said that in the US, each faculty position will have approximately 7.4 PhD students. Hence, if the number of positions does not grow over time, only 1 in 7.4 students (i.e. 13.5% of the PhD students) would be able to replace the faculty position.

- In table 10 of the UK report What do researchers do? it is said that 34% of PhD graduates work in academia, according to the L DLHE survey that we mentioned before. That survey takes place 3.5 years after graduation. Also, in table 11 it is indicated that 29% are doing research either in academia (16.7%, which is surprisingly low from the 34%, weird definitions perhaps) or industry (12.2%).

- There is a report on several central european universities showing the perspective of PhD holders. In figure 17 it is indicated that in the first two years, 60% are employed under temporal contracts, whether between 3 and 7 years, the number of permanent positions rises to 60%. Of the surveyed PhD alumni, 46% were employed in academia. Overall, 525/2299 = 22.8% of PhD alumni have attained a permanent position in academia and a number that raises to 26.8% 5-7 years after the end of the PhD.

In figure 25 it is also indicated that from the research employed people, 35% hold some postdoctoral position, and another 30% a research fellow or assistant professor position. - This research article also analises the amount of people that reach tenure positions for STEM PhD alumni. Figure 1c gives quite optimistic data, a 21% chance of tenured for the 0-5 years after PhD range, and 37% onwards.

- This graph on biology PhD students shows 15% of them get a tenured position within 6 years. However, they expect that <10% of new PhD students will get it.

The data is somewhat confusing and contradictory, probably because I am mixing non-comparable sources. In any case, other minor comments is that in Europe there seem to be higher chances (based on point 4) and that Biology seems harder than Physics and Chemistry

Percentage of PhD students who get a permanent position in academia according to each source above.

With respect to the amount of people who want to stay in academia I have found

- Some historical calculations are indicated in this newspaper article, where this other article is mentioned.

- In this other article, it is indicated that after the PhD, 80% of the graduates want to remain in academia, whereas that number drops to 60% after three years. It is also decomposed for CS in particular (80% and 73% respectively).

- This nature article has some statistics on expectations. It gives a ~70% interest in the academic career depending on the geographical zone; and indicates that Europe is the continent where people are more pessimistic about the time needed to get tenure.

Overall, my personal estimate is that I'm 90% sure that 10-30% of students get tenure, and 65% that the intervale is between 10% and 20%. Furthermore, I estimate based on the previous sources that around 70% of the PhD alumni would want to work in academia. Hence, conditional on wanting to work in academia your baseline chances should be in the 15-30% range to start with.

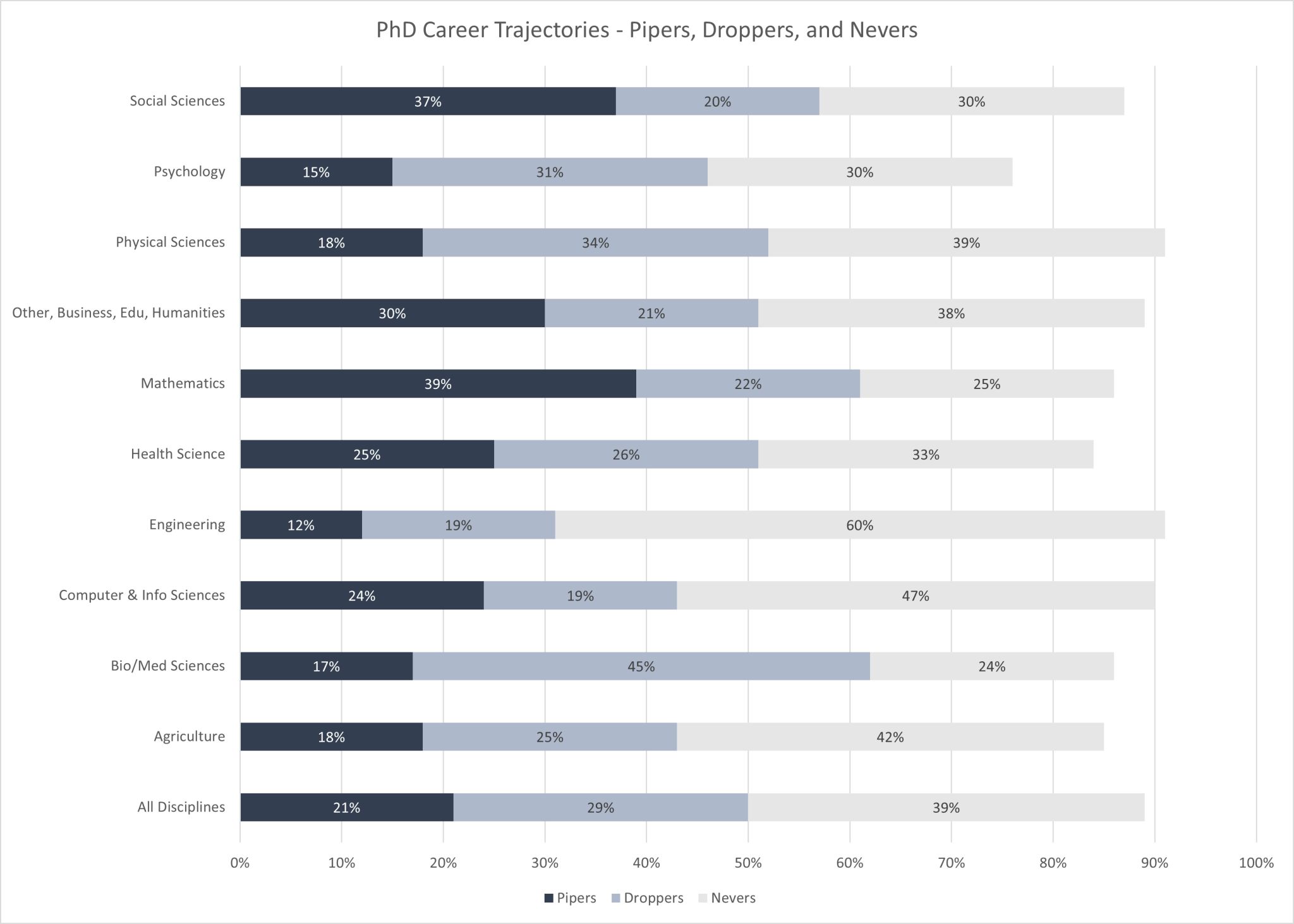

Update: Since I published this article, I have found this report, that decomposes probabilities by field of study in Concordia University, Canada:

The discipline with the highest percentage of tenure-track and tenured professors is business (69%) followed by social sciences (27%), humanities (22%), engineering (21%),fine arts (14%) and sciences (11%).

Update 2: I have found a second article on 7000 US STEM graduates detailing what percentage of people progress to the next stage, indicating that overall 21% of PhD holders get tenure, and that 24% do in Computer Science.

Pipers are those who get tenure, never are those who don't stay in academia after their PhD, droppers those who drop mid way.

Inside view: the predoctoral publication statistics

Some articles that are important in this respect:

- This article analyses several factors to predict the success of a given PhD graduate. It also says:

"Despite this, a relatively small percentage of individuals successfully completing a PhD ultimately achieve this goal, with only an estimated 14% of biological sciences PhD recipients having a tenure-track faculty position 5–6 years post graduation (Stephan, 2015). This rate is somewhat higher for earners of chemistry (23%) or physics (21%) PhDs." - This other article does the same for medical sciences, but has the nice feature of indicating the average rate of publications per year and number of authors.

- This article gives some explanation of different factors, including the sex, and number of publications of the PhD supervisor.

- Another article has an analysis of different factors for the field of sociology.

- Finally, there is another nice article on different average publishing rates in Norway, by fields, gender, age and position

Some conclusions from this section is that publishing and specially first-author publishing is the largest predictor of academic success. What is much harder to find is concrete numbers for particular fields.

Conclusion

I believe that having a more accurate estimate of what are the actual chances of landing a job at academia can help to gauge the pros and cons of this career path.

From the previous sections it is likely (65% chance in my opinion) that the probability baseline probability of landing a permanent job at academia conditional on trying is in the 15-30% range.

However, there is a lack of data on how exactly to use the inside view to gauge personal probabilities. In particular, most studies analysing this have been done for particular fields which may not replicate in others. However, the best estimate seems to be that if you are going this path, the main metric you should be looking at is the number of articles where you are the first author. More research is needed to calibrate estimates based on inside-view factors.

I would like to thank the incredible help of Jaime Sevilla, who provided useful feedback on a draft of this article.

Academic here:

1-15% without substantial prior research experience,

5-60% with limited research experience (at least one serious paper with a recognized collaborator, but nothing presented as a first author at a competitive venue)

50-90% with strong research experience (at least one paper with a recognized collaborator, presented as a first author at a competitive venue).

P(assistant professor job at a top-100 research university within three years after PhD | graduate within six years and apply) = 30-75%

P(long-term US research job that supports publishing, academic or otherwise, within three years after PhD | graduate within six years and apply) = 85-95%

Hey Pablo - thanks for working this up. It's nice to have some baseline estimates!

As you say, Tregellas et al. shows that the probability of tenure varies a lot with the number of first author publications. It would be interesting to know if tenure can be predicted better with other factors like one's institution or h-index - I could imagine such a model performing much better than the baseline.

Two other queries:

You're right Ryan, I'll modify the second complicated sentence. I am actually not sure what is the difference between tenure and tenure track, to tell the truth.

However, in one of the documents above I saw that institution is not such a strong predictor (point 4), but h index seemed useful (in point 2 the h-index is discussed).

Interesting. The point 2 article by van Dijk seems decent. Figure 1B says that the impact factor of journals, volume of publications, and cites/h-index are all fairly predictive. University rank gets some independent weighting (among 38 features, as shown in their supplementary Table S1), but not much.

Looks like although the web version has gone offline, the source code of their model is still online!

I strongly agree with Ryan that success is to a relatively large degree predictable, as can be done in the PCA decomposition of point 2 above, figure 1C.

I think it would be very valuable to have such a model, but the current code is only for biology (the impact factor will fail for instance for anything different). If one wanted to fit a model to predict it, it could probably use google scholar and arxiv, but the trickiest part would be to recover the position of those people (the target), which may partially be done using google scholar.

I just posted another article I found on average publication rates in Norway for different positions, ages, fields and gender.

This is helpful, thanks.

The information is probably here somewhere, but is that the probability of getting tenure given you finish your Ph.D.? I.e. Does this account for dropping out?

Somewhat tangential, but I think accounting for the chance of working on AI safety (or something comparably effective) outside of academia will help. I think this is more common in Economics (e.g. World Bank). But I guess OpenAI or similar institutions hire CS PhDs and working there possibly has a similar impact to working in academia.

I would say you basically cannot get tenure if you don't get a PhD, so dropouts are not taken into account in any of the previous statistics as far as I understood them. All this metrics are of the kind of: x% of PhD alumni got tenure, or similar.

I actually agree that taking into account the private sector could help, but I am much less certain about the freedom they give you to research those topics, beyond the usual suspects. That was why I was focussing on academia.

In the US, about half of people who start PhD programs get the degree. Also, a big factor that I thought I commented about here (I guess they removed comments) is that most tenure track positions at least in the US are teaching intensive, so there is not much time for research.