Abstract

Eli Dourado presents the case for scepticism that AI will be economically transformative near term[1].

For a summary and or exploration of implications, skip to "My Take".

Introduction

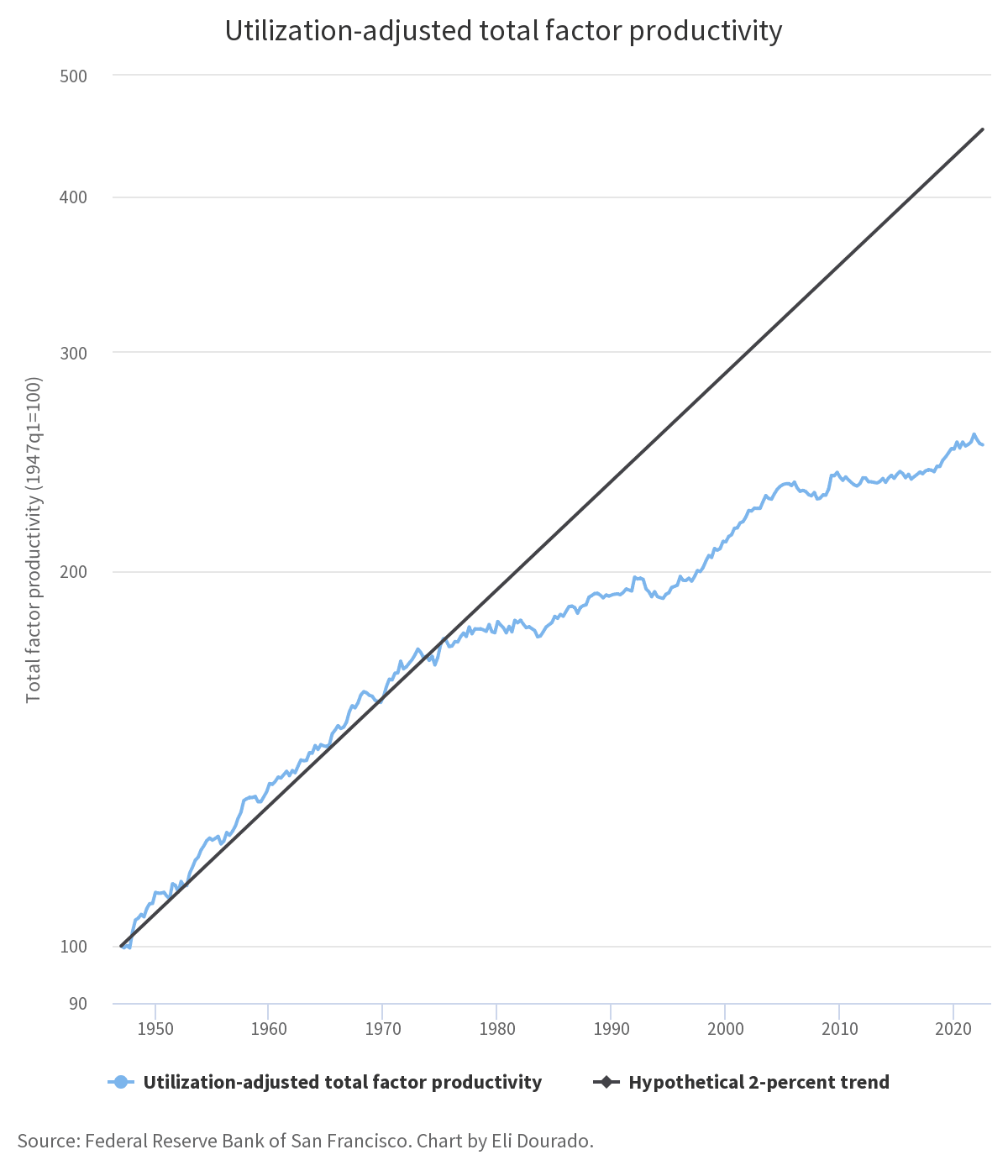

Fool me once. In 1987, Robert Solow quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Incredibly, this observation happened before the introduction of the commercial Internet and smartphones, and yet it holds to this day. Despite a brief spasm of total factor productivity growth from 1995 to 2005 (arguably due to the economic opening of China, not to digital technology), growth since then has been dismal. In productivity terms, for the United States, the smartphone era has been the most economically stagnant period of the last century. In some European countries, total factor productivity is actually declining.

Eli's Thesis

In particular, he advances the following sectors as areas AI will fail to revolutionise:

- Housing

- Most housing challenges are due to land use policy specifically

- He points out that the internet did not break up the real estate agent cartel (despite his initial expectations to the contrary)

- Energy

- Regulatory hurdles to deployment

- There are AI optimisation opportunities elsewhere in the energy pipeline, but the regulatory hurdles could bottleneck the economic productivity gains

- Transportation

- The issues with US transportation infrastructure have little to do with technology and are more regulatory in nature

- As for energy, there are optimisation opportunities for digital tools, but the non-digital issues will be the bottleneck

- Health

- > The biggest gain from AI in medicine would be if it could help us get drugs to market at lower cost. The cost of clinical trials is out of control—up from $10,000 per patient to $500,000 per patient, according to STAT. The majority of this increase is due to industry dysfunction.

- Synthesis:

I’ll stop there. OK, so that’s only four industries, but they are big ones. They are industries whose biggest bottlenecks weren’t addressed by computers, the Internet, and mobile devices. That is why broad-based economic stagnation has occurred in spite of impressive gains in IT.

If we don’t improve land use regulation, or remove the obstacles to deploying energy and transportation projects, or make clinical trials more cost-effective—if we don’t do the grueling, messy, human work of national, local, or internal politics—then no matter how good AI models get, the Great Stagnation will continue. We will see the machine learning age, to paraphrase Solow, everywhere but in the productivity statistics.

Eli thinks AI will be very transformative for content generation[2], but that transformation may not be particularly felt in people's lives. Its economic impact will be even smaller (emphasis mine):

Even if AI dramatically increases media output and it’s all high quality and there are no negative consequences, the effect on aggregate productivity is limited by the size of the media market, which is perhaps 2 percent of global GDP. If we want to really end the Great Stagnation, we need to disrupt some bigger industries.

A personal anecdote of his that I found pertinent enough to include in full:

I could be wrong. I remember the first time I watched what could be called an online video. As I recall, the first video-capable version of RealPlayer shipped with Windows 98. People said that online video streaming was the future.

Teenage Eli fired up Windows 98 to evaluate this claim. I opened RealPlayer and streamed a demo clip over my dial-up modem. The quality was abysmal. It was a clip of a guy surfing, and over the modem and with a struggling CPU I got about 1 frame per second.

“This is never going to work,” I thought. “There is no way that online video is ever going to be a thing.”

Exponential growth not only in processors but also in Internet speeds made short work of my denunciation of video streaming. I think of this experience often when I make predictions about the future of technology.

And yet, if I had only said, “there is no way that online video will meaningfully contribute to economic growth,” I would have been right.

My Take

The issues seem to be that the biggest bottlenecks to major productivity gains in some of the largest economic sectors are not technological in nature but more regulatory/legal/social. As such, better technology is not enough in and of itself[3] to remove them.

This rings true to me, and I've been convinced by similar arguments from Matt Clancy to be sceptical of productivity gains from automated innovation[4].

Another way to frame Eli's thesis is that for AI to quickly transform the economy/materialise considerable productivity gains, then we must not have significant bottlenecks to growth/productivity from suboptimal economic/social policy. That is, we must live in a very adequate world[5]; insomuch as you believe that inadequate equilibria abound in our civilisation, then apriori you should not expect AI to precipitate massive economic transformation near term.

Reading Eli's piece/writing this review persuaded me to be more sceptical of Paul style continuous takeoff[6] and more open to discontinuous takeoff; AI may simply not transform the economy much until it's capable of taking over the world[7].

- ^

By "near term", I mean roughly something like: "systems that are not powerful enough to be existentially dangerous". Obviously, existentially dangerous systems could be economically disruptive.

- ^

He estimates that he may currently have access to a million to ten million times more content than he had in his childhood (which was life changing), but is sceptical that AI generating another million times improvement in the quantity of content would change his life much (his marginal content relevant decisions are about filtering/curating his content stream).

- ^

Without accompanying policy changes.

A counterargument to Eli's thesis that I would find persuasive is if people could compellingly advance the case that technological innovation precipitates social/political/legal innovation to better adapt said technology.

However, the lacklustre productivity gains of the internet and smartphone age does call that counterthesis into question.

- ^

As long as we don't completely automate the economy/innovation pipeline [from idea through to large scale commercial production and distribution to end users], the components on the critical path of innovation that contain humans will become the bottlenecks. This will prevent the positive feedback loops from automated innovation from inducing explosive growth.

- ^

I.e. it should not be possible to materialise considerable economic gains from better (more optimal) administration/regulation/policy at the same general level of technological capabilities.

In game theoretic terms, our civilisational price of anarchy must be low.

However, the literature suggesting that open borders could potentially double gross world product suggests that we're paying a considerable price. Immigration is just one lever through which better administration/regulation could materialise economic gains. Aggregated across all policy levers, I would expect that we are living in a very suboptimal world.

- ^

A view I was previously sold on as being the modal trajectory class for the "mainline" [future timeline(s) that has(have) a plurality(majority) of my probability mass].

- ^

I probably owe Yudkowsky an apology here for my too strong criticisms of his statements in favour of this position.

I like the way you summarized this, thanks!

You're welcome.

Happy to be useful!

I wonder about the implicit assumption that AI is neutral wrt advancing progressive policy.

For example, you could probably use LLMs today to mass produce letters of support for specific developments. Very soon, they'll be eloquent and persuasive as well.

You'll be able to do the same to argue for better legislation, and eventually automate CBO-style scores that are both more specific and more robust.

Of course, this could become an arms race, but I would hope that the superior facts of the progressive policies would mean it is an uneven one.

I like that housing is one of the big things mentioned that AI will not change. I’m consistently surprised by how low EA rates land-use reform.

I may just not be well-run enough, but are there any major EA organizations or donations going towards land policy?

Open Phil grants quite a bit to land use reform https://www.openphilanthropy.org/grants/?q=&focus-area[]=land-use-reform

Thanks for the link!

Edit: looks like the total is around $20 mil to land use reform. Still a good amount but I’d think it would be a higher priority.

Historically it has looked quite intractable, but I'd say that's changing recently and may spur more grants.

The bigger problem though is it's a first-world issue, so you automatically get a big haircut on cost effectiveness. Even so, this is one of only a handful of things that are prioritized for those geos.

I think looking at policy specifically can be first world and narrow, but I’m with a company looking to raise the accuracy of property assessment period, and I think there’s a lot of impact to be had there.

For instance we’ve worked with some poor Eastern European countries who are only now getting proper data collection and models set up, which will help them tax much more effectively, as well as help stabilize their real estate market. It’s still early days though!

I’d like to think proper land management is also crucial going from third or second world to first world, as Scott points out in his review of How Asia Works. https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/book-review-how-asia-works

From the post we don't get information about the acceleration rate of AI capabilities but on the impact on the economy. This argument is thus against slow takeoff with economic consequences but not against slow takeoff without much economic consequences.

So updating from that towards a discontinuous takeoff doesn't seem right. You should be updating from slow takeoff with economic consequences to slow takeoff without economic consequences.

Does that make sense?

Paul Christiano operationalizes slow/soft takeoff as:

Though there are other takeoff-ish questions that are worth discussing, yeah.

Thanks for this clarification! I guess the "capability increase over time around and after reaching human level" is more important than the "GDP increase over time" to look at how hard alignment is. It's likely why I assumed takeoff meant the former. Now I wonder if there is a term for "capability increase over time around and after reaching human level"...

I guess I don't understand how slow takeoff can happen without economic consequences.

Like takeoff (in capabilities progress) may still be slow, but the impact of AI is more likely to be discontinuous in that case.

I was probably insufficiently clear on that point.

Yes. In a slow takeoff scenario where we have AI that can double GDP in 4 years, I don't regulations will stand in the way. Some countries will adopt the new technologies and then other countries will follow when they realize they are falling behind. NIMBYs and excessive regulations are a problem for economic growth when GDP is growing by 2% or 3% but probably won't matter much if GDP is growing by 20% or 30%.

I love this post, and I'm not convinced by some of the counters in the comments. (e.g., I don't think LLMs will help persuade anyone of anything.)

This Ezra Klein podcast is really good, if you haven't heard it.