Note: This blog post was written for a U.S. audience given our highly complex tax system!

If you spend any time listening to personal finance podcasts or scrolling through money blogs that cover giving, you’ll notice an unmistakable theme: How to optimize your charitable giving for taxes.

“Make a tax-deductible donation today!”

“Bundle three years of donations!”

“Use a DAF to make your deductible donation!”

These statements aren’t wrong so much as they’re incomplete or misleading. Because when the entire conversation is framed around tax optimization, we miss the far more important question: How can I actually make a difference?

As someone who works at the intersection of personal finance and philanthropy, and as someone who gives regularly myself, I believe tax benefits are useful, but they should never be the reason you donate. They should be the supporting actor, not the main character.

Below is a no-B.S. breakdown of charitable tax breaks, why most people focus on the wrong things, and what everyday givers should actually prioritize.

Here are the 4 main types of charitable tax breaks you can get:

- Tax deductions for itemizers

- Qualified charitable distributions (QCDs) - 70½ years old

- Avoiding capital gains tax (appreciated assets only)

- "Above-the-line" tax deduction for non-itemizers (starting 2026)

Charitable tax deductions for itemizers

People in particular are obsessed the idea of tax deductions. So let's cover this first.

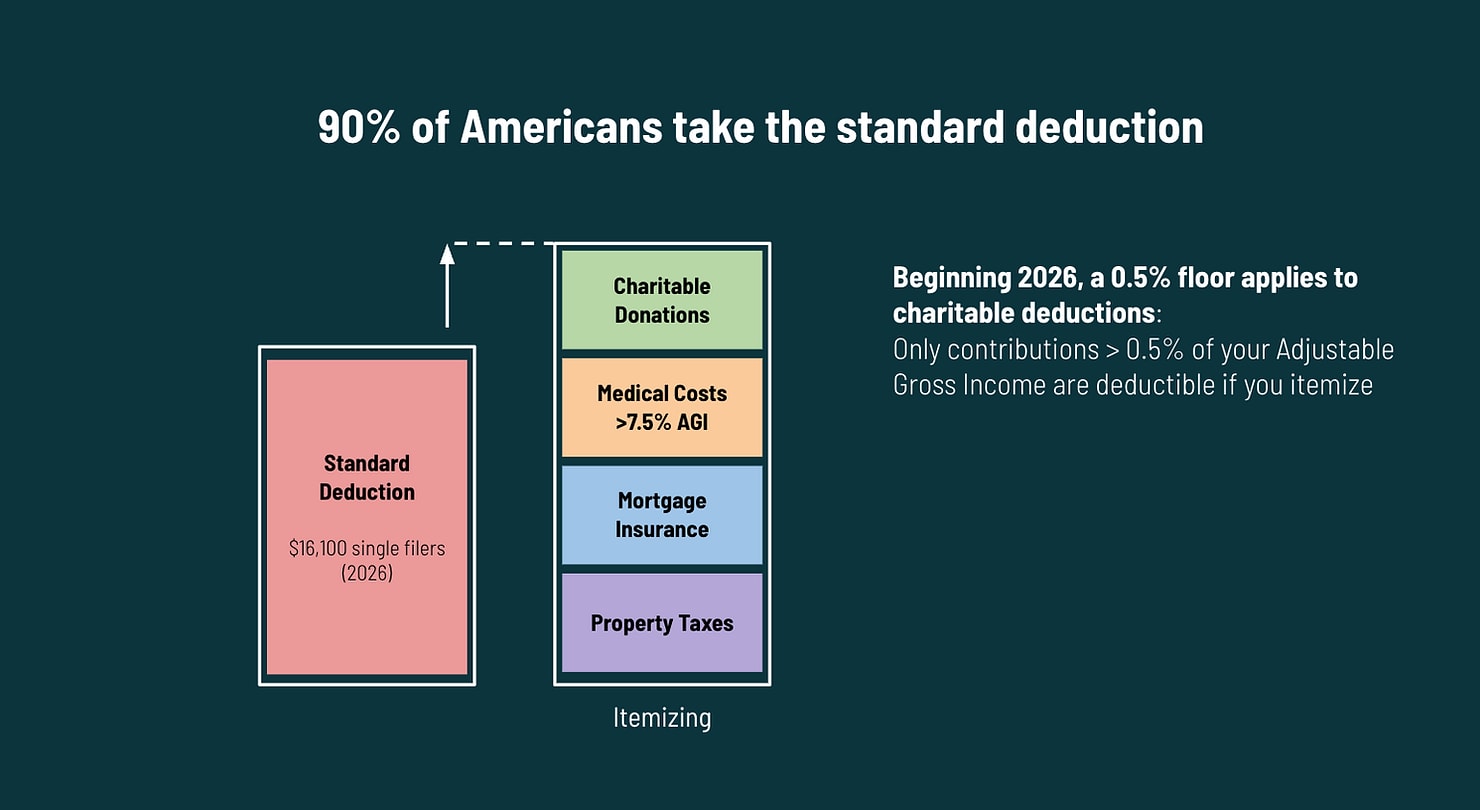

When you file your taxes, you’ll have the option to take the standard deduction or to itemize. The standard deduction is a specific dollar amount that reduces your taxable income. Most people, in fact 90% of US tax payers, take the standard deduction because it is so darn high: $16,100 for single filers (2026). Those who choose to itemize should only do so if their tax-deductible expenses, like mortgage interest and charitable giving, add up to more than the standard deduction.

So even if you donate meaningful sums of money each year, you may still find it still makes sense to take the standard deduction. For example, if you donate 10% of your $100,000 income, this alone isn't enough to warrant itemizing.

Furthermore, starting in 2026, charitable deductions for itemizers face a 0.5% Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) floor. Meaning: the first 0.5% of your income given to charity isn’t deductible at all. Another, albeit small, hurdle to itemizing.

So hopefully you can see quite clearly that itemizing isn't the most appealing for the average-sized donor. With that said, if you're still obsessed with the idea of itemizing, you may then be asking the following question: should I bunch my donations into a single tax year?

Maybe.

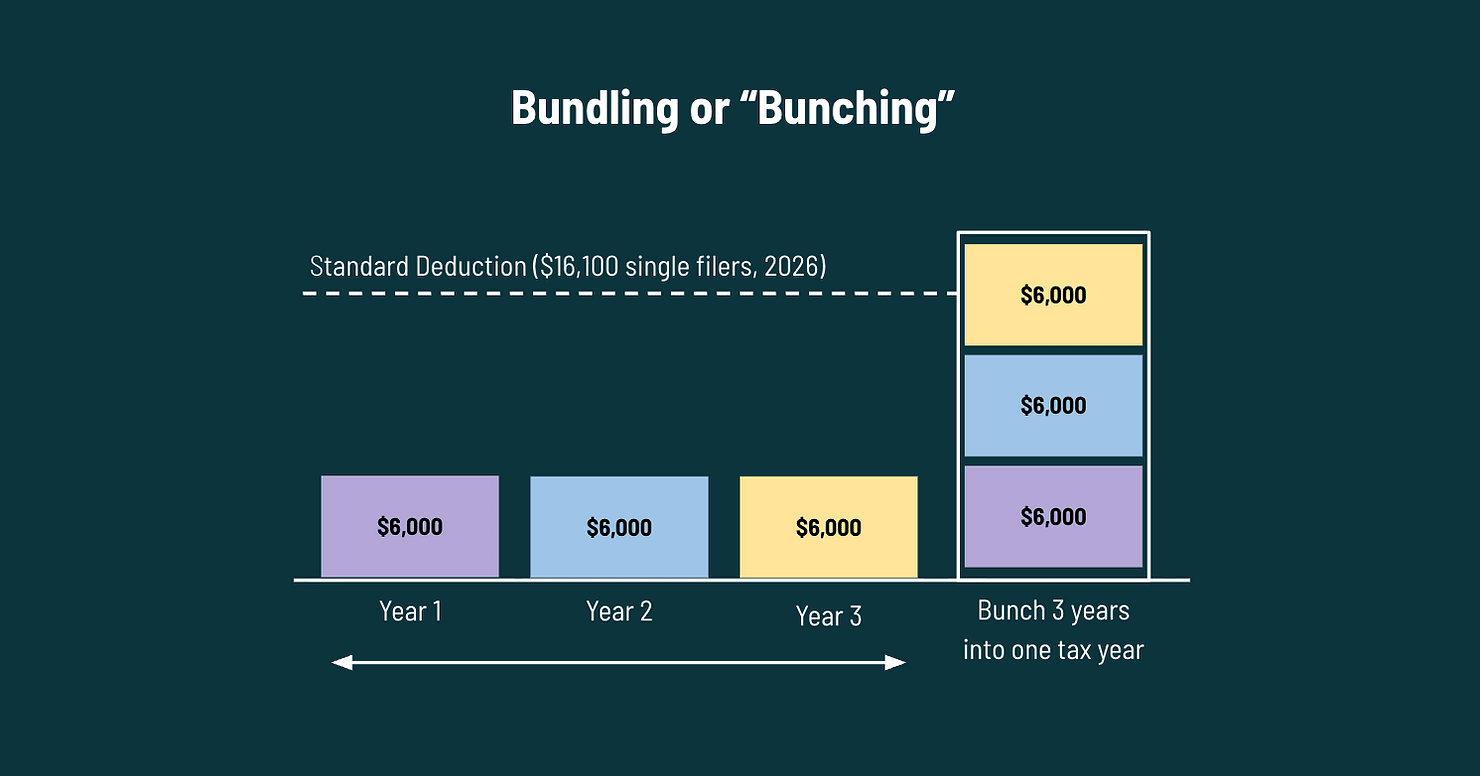

Bundling or "Bunching" to exceed the standard deduction

Bundling (donating multiple years of donations into one) is often framed as a clever hack. Perhaps instead of three consecutive years of donating $10,000, you decide to bunch $30,000 worth of donations into one year. This move surely warrants itemizing and will result in a tax deduction. And perhaps that deduction is large enough to push you down into a lower marginal tax bracket. Double-win!

From a tax perspective, this is then a no brainer. But bundling has an unspoken downside: it disrupts your giving habit.

If you give only once every 3-5 years, I personally think you’re not building a habit of giving. And furthermore charities lose the consistency they rely on. I’d much rather see someone give every year, even if it means paying a little more in taxes, than wait years just to gain a small tax benefit. Ultimately, it's up to you to decide how much of a tax benefit you need to outweigh the consistency of giving. If you ask me, I think it should be at least five-figures, especially if spread out over multiple years.

One argument against this is incorporating the use of a donor-advised fund (DAF), which enables you to make consistent donations over time but allows you to make a large contribution today and receive tax benefits (more on whether or not a DAF is right for you here).

Since tax deductions are less applicable to the everyday donor, what tax breaks are more relevant?

1. The New Above-the-Line Deduction (starting 2026)

Beginning in the 2026 tax year, there will be a $1,000 deduction for single filers (or $2,000 for those married filing jointly) available to those who take the standard deduction and make their donation in cash to qualified public charities.

This is a no brainer to deploy. And I think it actually creates a really good threshold for folks. Is there a world in which you could donate $1,000 a year? That’s only a little over $80 a month.

2. Capital Gains Tax Avoidance (donating appreciated assets)

If you donate stocks, bonds, or funds that have gone up in value, without selling them first, you skip capital gains tax on those assets entirely. This is a powerful tool that anyone with a investment account can use. You do not need a DAF to do this.

3. Qualified charitable distributions (QCDs)

For anyone aged 70½ or older with a traditional IRA, QCDs let you give directly to charity straight from your IRA, and the amount you give is excluded from your taxable income. Once you hit the age where Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) kick in, QCDs can also satisfy part or all of your RMD, which means you’re reducing your tax bill and supporting causes you care about.

This is one of the most overlooked tax benefits out there, especially for retirees who don’t itemize. If you’re already planning to give, using QCDs is often the most tax-efficient way to do it.

But of course, if you’re not in your seventies, this won’t apply to you yet.

Ultimately, it’s consistency and impact that matters in your giving.

I’m happy to cover topics like this, and if you have any doubts, you should absolutely consult a tax advisor. But for me, regular and thoughtful giving beats most tax optimizations strategies.

What’s most important is that you build a habit. Here are the 4 steps I often recommend:

- Identify your charities: Mark your calendars once or twice a year and spend time to identify charities that can do the most good. This way you won’t feel burdened in having to make this decision over and over again each time you want to donate.

- Set a schedule: I think monthly giving works best. Get this on your calendar or link it up to something else you’re already doing (like a monthly finance meeting)

- Decide what you want to donate: What you are materially going to donate: cash? stocks? grants from your donor-advised fund (DAF)? Make sure to check that your charities accept the type of asset you want to donate

- Re-evaluate: Set time to re-examine your strategy. Did you miss the money? Did you experience financial hardship? Are you perhaps happy to see all that you have donated?

For more comprehensive overview of charitable tax deductions, you can check out Yield & Spread's free Giving Guide.

We also have a 4-part series on Donor-Advised Funds and whether or not they are right for you

About Me:

I'm an early retiree a la the FIRE movement and a 10% Pledge-Taker. I run a non-profit called Yield & Spread, dedicated to helping people build financial confidence so that they can give back. Check out our Learn to Invest course, free resources, and coaching program. Reach out with any questions!

Disclaimer: The information in this post is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended to substitute for obtaining accounting, tax, or financial advice, and may not be suitable for every individual. Yield & Spread is not a registered investment, legal or tax advisor or a broker/dealer.

Executive summary: The post argues that most charitable giving advice overemphasizes itemized tax deductions, which are irrelevant for most U.S. donors, and that consistent, impact-focused giving matters more than tax optimization, with a few specific tax tools being genuinely useful.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Thanks Rebecca! This is great.

I really appreciate your callout to donating appreciated stocks, and I really hope this becomes a common activity: "The New Above-the-Line Deduction (starting 2026) This is a no brainer to deploy. And I think it actually creates a really good threshold for folks. Is there a world in which you could donate $1,000 a year?"