TL;DR: Cost-effective giving can excuse moral slip-ups in daily life. I suggest pairing it with small, personal acts of giving to stay grounded.

I’m sharing this to reflect on my struggles and get advice from the EA community.

When I was in secondary school and sixth form, I used to never do home clothes day. I gained a bit of a reputation as somebody who didn't care about charity, eager to save £2 (home clothes days have gotten damn expensive recently).

There were other reasons; Most of the time I'd genuinely forget. I also used to have some really crap clothes, so I didn't want my friends to see those. But the main reason was that I was influenced by effective altruism. Because most of these charities were especially cost-ineffective, I would think 'that money would be better off spent elsewhere'.

But then: I wouldn't take up that challenge. I'd give money to cost-effective charities - but I wasn't giving that specific £2. I'd have a misplaced sense of satisfaction (which I kind of experienced as that warm glow of giving) and keep the money.

Me, 13, emerging from this cave; I look like I've been in there for years.

Since I started working in a shop and giving 10% of my income, I've noticed this problem has been getting worse. Often someone asks for my help, unless I'm very close to them, I think 'I could use this time more effectively to help other people'. And then I don't! I take the moral obligation off my shoulders without helping anybody.

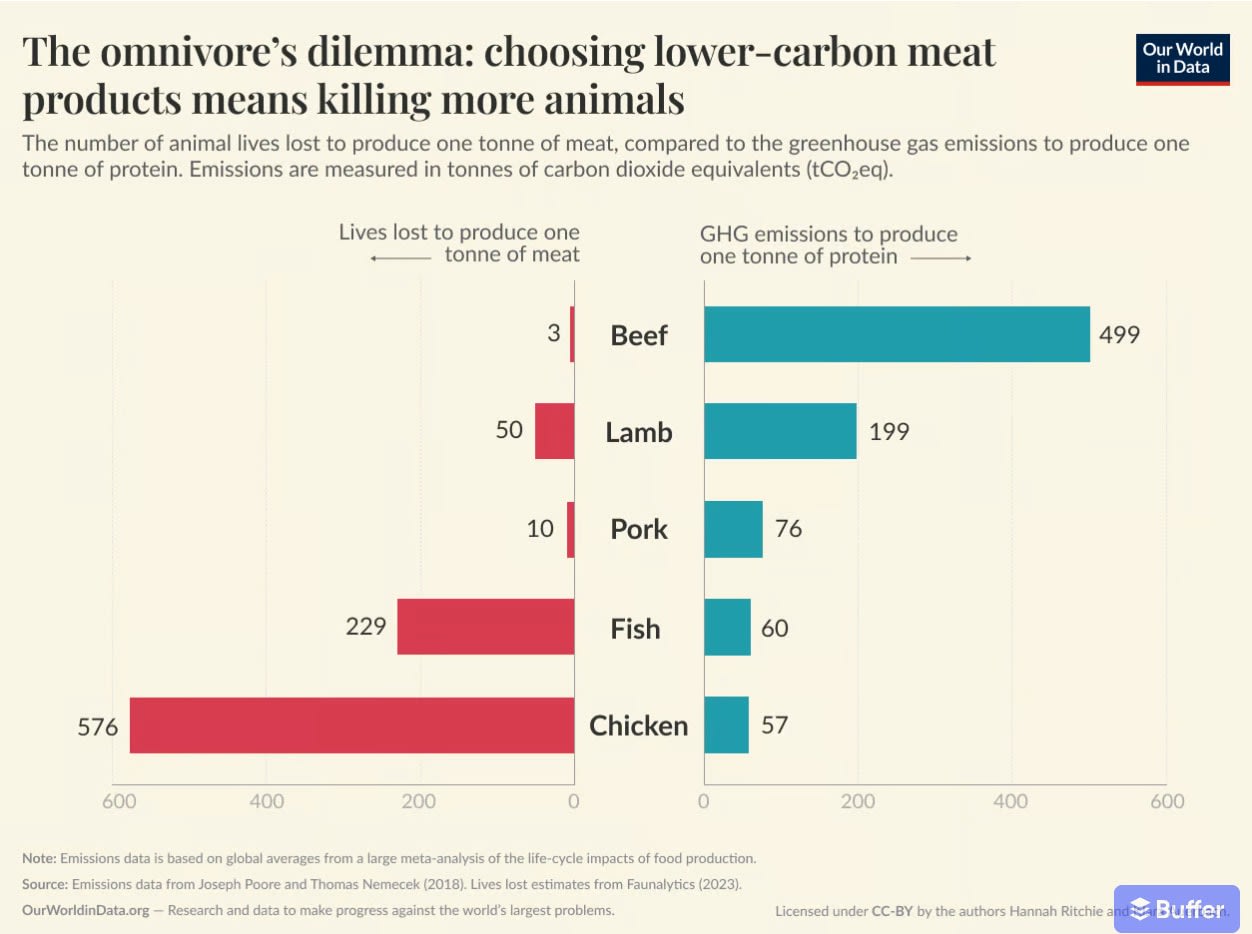

Even more, I've noticed that my donations sometimes make me feel like I have a 'free pass' on certain moral decisions. For example, I still eat meat, using the justification that my donating to animal welfare charities far outweighs the moral loss of eating meat.

I’m sure I’m not alone in this.

A Tentative Solution

I've noticed that giving 10% at first gave me that warm fuzzy feeling, but it no longer does - and I think that's kind of the point. To turn it into such a habit that you do it without even thinking about it.

That means I have an opportunity to give more, in one way or another. I could start giving more than 10%, but part of the problem with that is that it might lose the subconscious element that allows for massive amounts to accumulate over a lifetime.

Perhaps then there's a place for actively practicing selfish giving alongside cost-effective giving; giving my time to help the people around me, even if its not the most cost-effective. Here are some benefits I foresee:

- Improving my own wellbeing by being more connected to and liked by others.

- By being more moral in my daily life, I can convince others (with more influence than me) that giving cost-effectively is something amazing.

- Most importantly, grounding my morals in actually helping people can help reaffirm why I'm doing this. I feel very far removed from the place I started looking at EA from.

I hope this post didn't make me sound bad, but it's something I'd really like advice on. I'd love to hear how others in EA balance these tensions. Have you experienced similar struggles, and if so, what helped you?

Cool topic.

This is the key one to meditate on.

For me at least signing the giving pledge was a year of internalising that I have these values and I must eat them. Otherwise these aren't my values after all. Likewise for the standards of being a good friend, father, flutist etc.