18/11/2024 EDIT: Updated with more links and added Biosecurity.world which has now been built.

Thank you to the following people for reviewing: @Lin BL @Tessa @Max Görlitz @Gregory Lewis, Sandy Hickson & @Alix Pham

TL:DR

- Getting a full-time role in biosecurity is hard

- Seeing a path to get there can be even harder

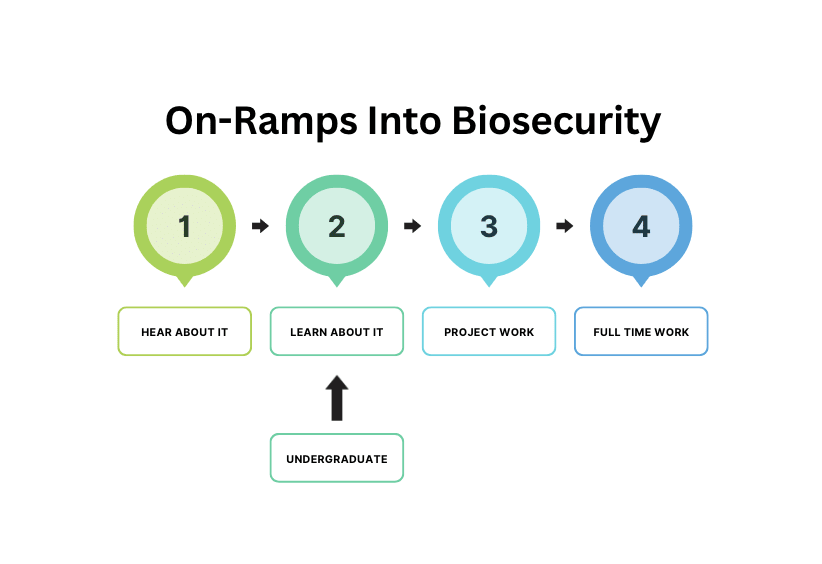

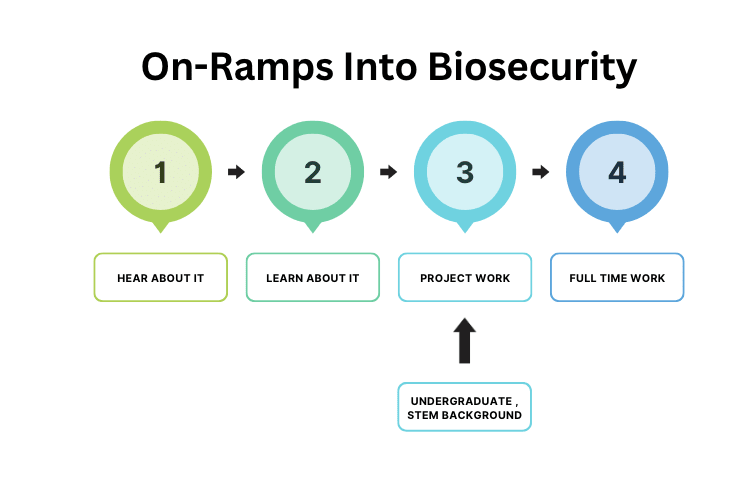

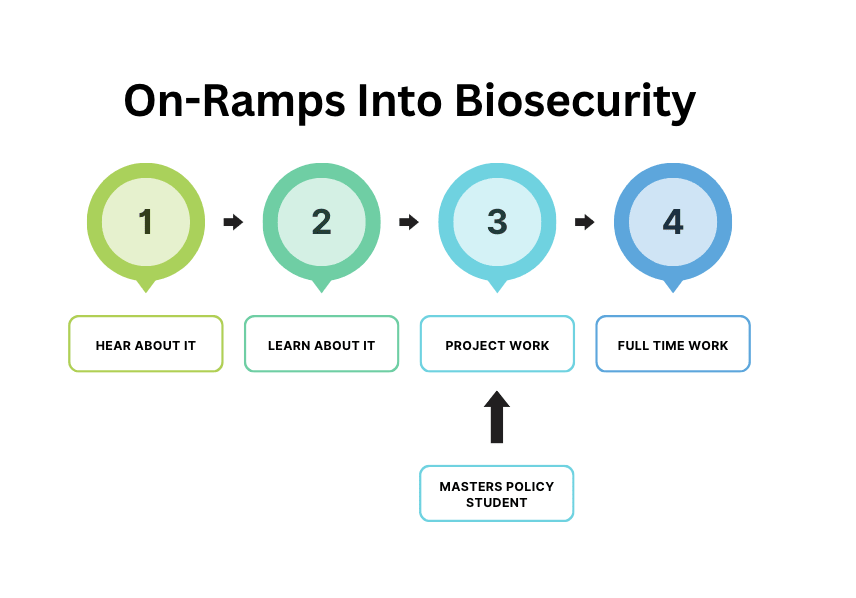

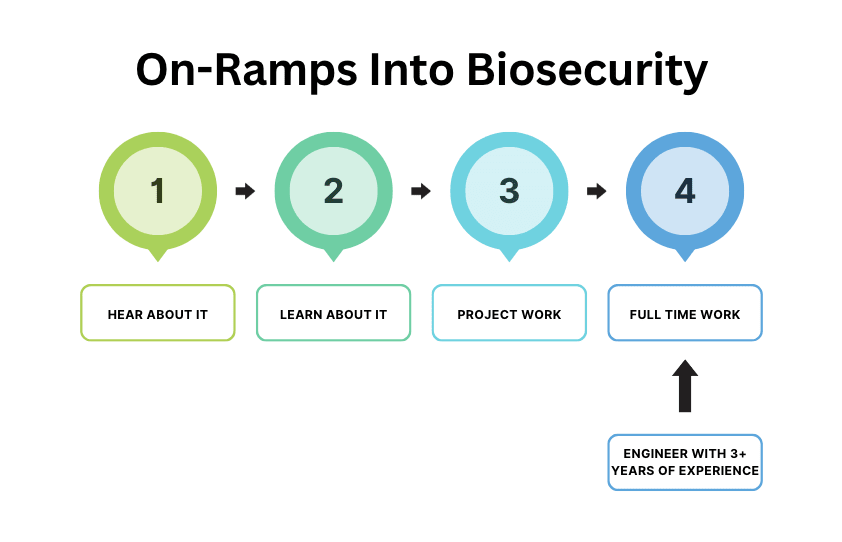

- I propose a model to think about on-ramps into biosecurity & provide a few use cases for it depending on the background you are coming in with.

- I provide an overview of how different organisations in this space fit into the model.

- If you are an undergrad check the "I'm new to Biosecurity, where do I start?".

A common problem

When I first heard about biosecurity I was excited by the 80,000 hours podcast and impressed by the work of Kevin Esvelt, RAND and NTI. Even though I was studying molecular biology, a seemingly relevant subject I couldn’t see a way for me to get involved and to find a full-time role in this field. The gap between hearing about biosecurity and working full-time in biosecurity felt huge.

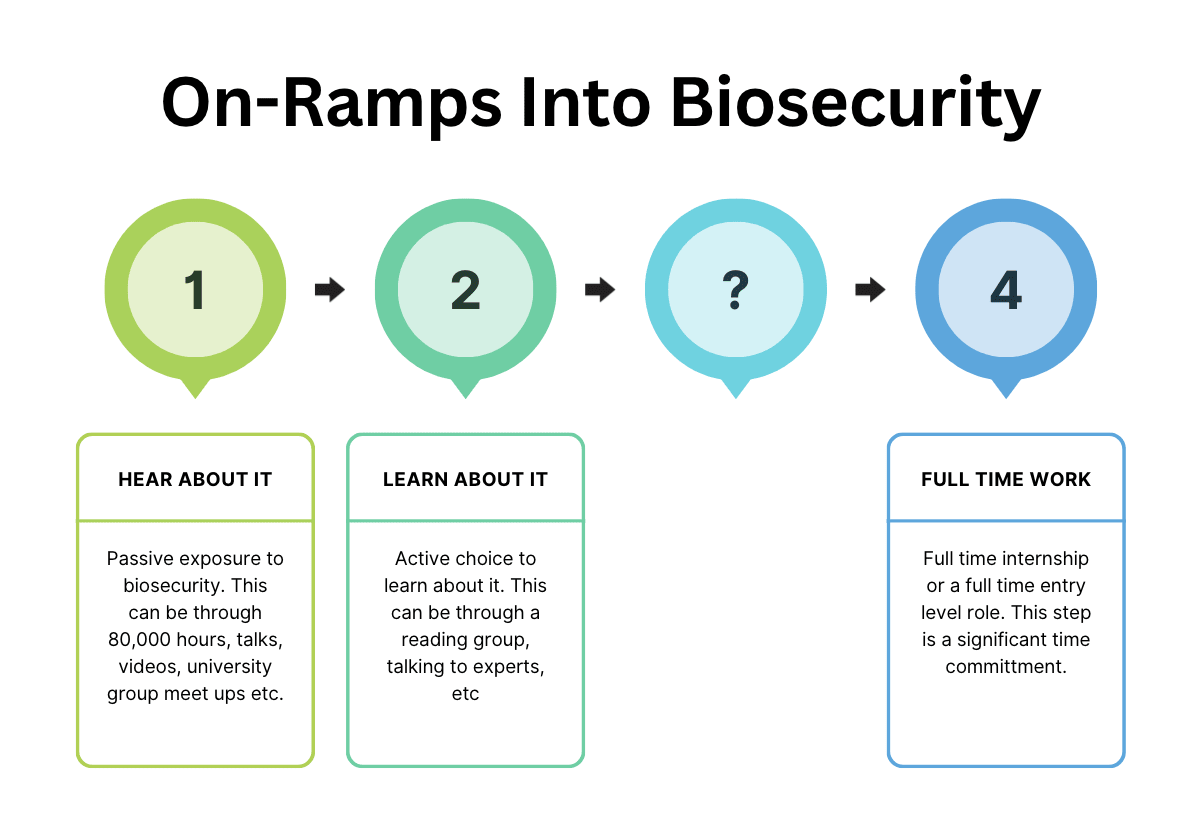

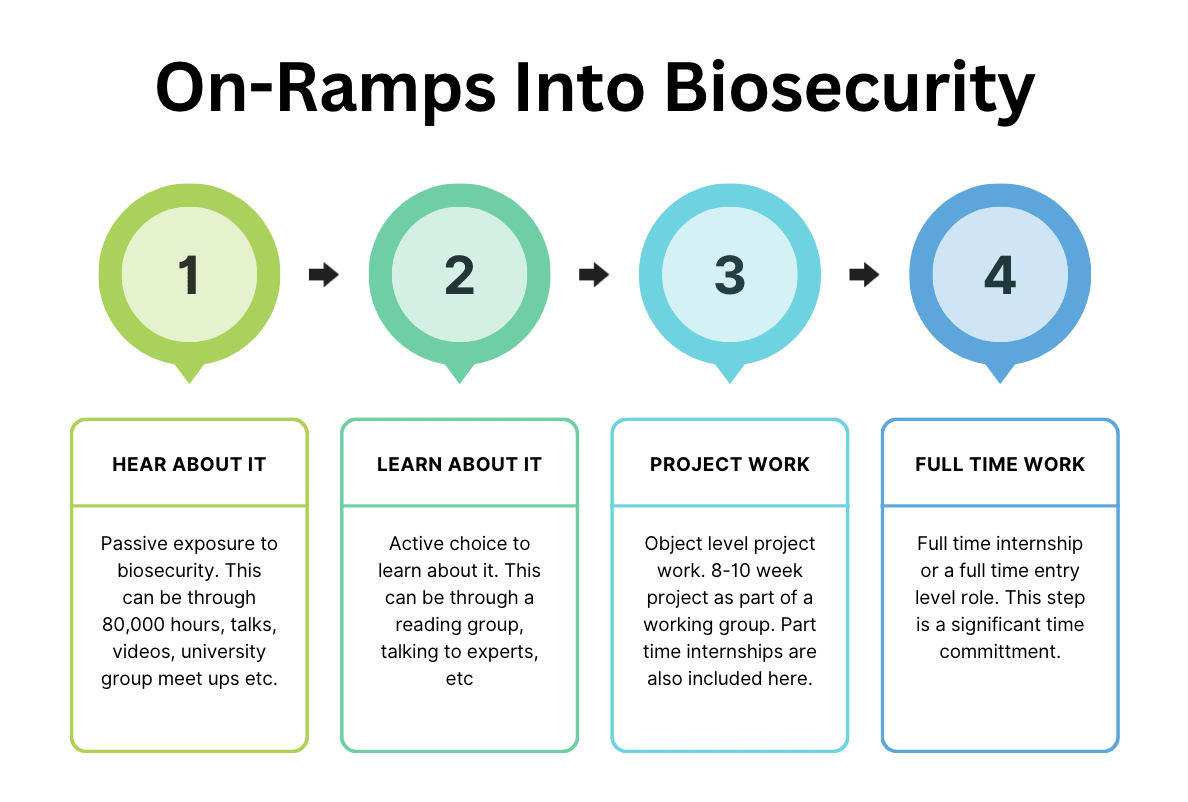

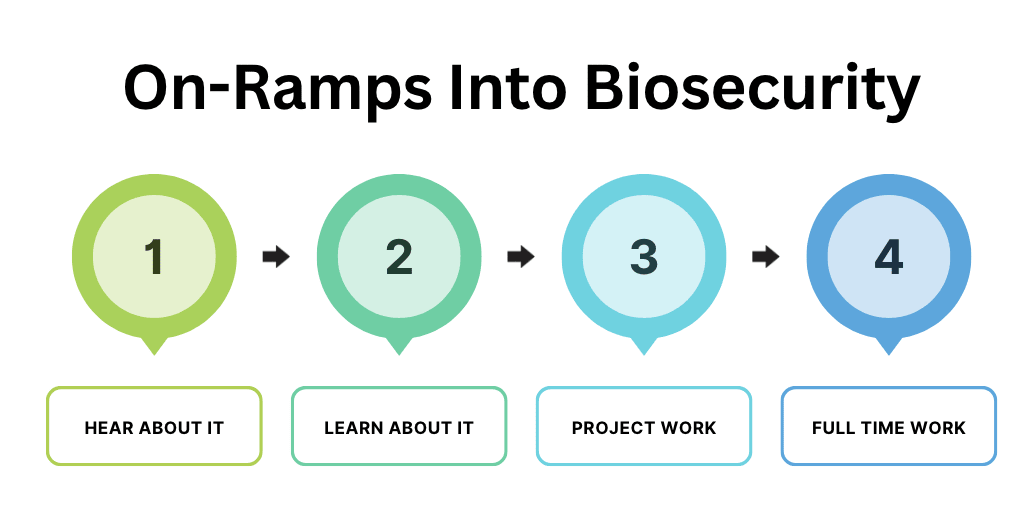

A proposed on-ramp model

Through my experiences with reading groups, UC Berkeley EA, SERI BITS and now the Oxford Biosecurity Group I have found that working on short, object-level, scalable projects fills this gap. And since I get questions of how to fill the gap from others new to the field I made a model to explain my thoughts.

Using the model

Below I outline some touch points that people have with various organisations in the biosecurity space. It’s important to note that this model is not always linear. It’s important to question your assumptions at every stage and the “stages” themselves can be more fluid.

Hear about it (0 - 10 hours)

This stage can be passive or active depending on your timeline. Note that a lot of the 'hear about it' resources can also be 'learn about it' resources if they are used for more in-depth research at a later stage.

- 80,000 Hours

- EA Forum (hehe)

- GCBR Organization Updates Newsletter

- Biosecurity newsletters you should subscribe to

- University Groups

- Your local EA Group

Learn about it (10 - 40 hours)

This stage usually takes around 1-2 months and is more passive.

- Biosecurity.world - Landing page for biosecurity

- List of Short-Term (<15 hours) Biosecurity Projects to Test Your Fit

- Pandemics Interventions Course is a static list of readings for biosecurity

- Reading groups at your university

- Reading groups at your local EA Group

- Find peers (at a similar career stage to you and you can exchange ideas with)

- Find mentors (who can help you deliberate between next steps in your career)

- Find experts (who can help you deliberate on technical differences between projects and provide insights into specific sub-fields)

- Taking to relevant people in the field, building a network

- BlueDot Impact Biosecurity Fundamentals

- Emerging Tech Policy Careers

- Effective Thesis research questions Airtable

- Biosecurity Network (you can join if you are early career)

Project Work (40 - 100 hours)

This stage usually takes around 2-3 months and is more active. You are encouraged to continue building out your network of peers, mentors and experts and possibly to form your working group to think about these concepts. However my suggestion would be to do project work as a part of some formal group/institution if possible, to make sure that you work on something valuable.

- Biosecurity Working Groups

- Oxford Biosecurity Group

- Wisconsin Biosecurity Initiative

- Cambridge Biosecurity Group (contact: Sandy Hickson)

- Nordic Biosecurity Group (contact: Johan Täng)

- Next Generation for Biosecurity Competition

- BlueDot Impact Biosecurity Fundamentals (second part of the course)

- St Gallen Symposium Essay competition

- Mentorship Programs

- Short-term, full-time fellowships

Full-Time Work (100 hours +)

- A more extensive list of organisations has been compiled below

- Career Development Funding from Open Philanthropy

- A Ph.D. in a relevant field, if you are excited by research

- Working in government where a lot of the most impactful biosecurity work is done.

- Organisations from Biosecurity.world

- Horizon Institute for Public Policy

- FAS Day One Project

- CLTR

- RAND

- Emerging Leaders in Biosecurity Fellowship (for people later in their careers)

* Note the full-time section is by no means exhaustive

Limitations of the model

- The path is not linear

- You can go back and forth between the stages. You can skip a stage.

- There are other ways to get into biosecurity

- There are other paths to working on biosecurity, like working in an adjacent field and then pivoting. This could sometimes put you in a stronger position to work in biosecurity, though this might take longer.

- This model skips out on critical thinking (Tessa’s alternative model below)

- Hear about it

- Learning to decide whether you're interested

- Starting to generate your own ideas/opinions

- Starting to contribute

- Making contributions in a more defined area

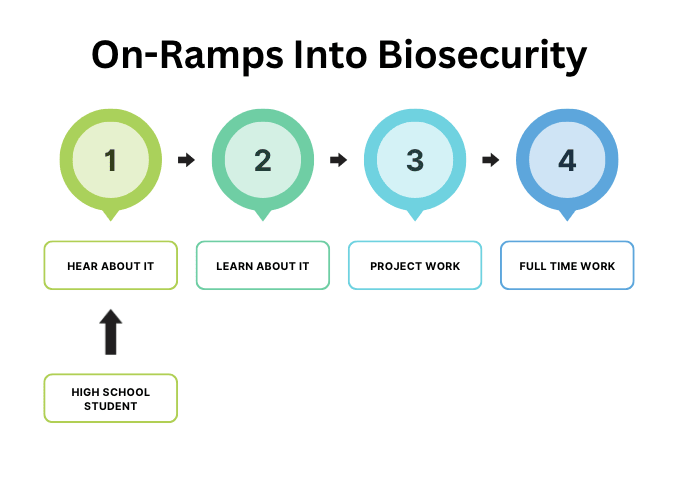

I’m new to Biosecurity, where do I start?

A step-by-step guide:

- Identify where in the diagram you are (see below for example case studies)

- Have a look at the Map of Biosecurity Interventions and the Map of the biosecurity landscape and also Biosecurity.world.

- Pick 3-5 key areas that you are interested in

- Pick 3-5 key skills you are interested in developing

- Now identify learning or work opportunities to test out 3&4

Below I include use cases of this model with a few example backgrounds. These are just examples and if you feel ready for full-time work but have less experience than I have specified, please do not be dissuaded.

Case Studies

- High school student

- Undergraduate with no specific background

- Undergraduate STEM background

- Masters policy student

- Engineer with 3+ years of experience

What’s next?

Biosecurity.world has been built.

Awesome work, thanks! And this model resonates with my experience getting more involved with bio over the last few years.

Wonderful to hear that!

Thanks a lot for writing this up, it'll be useful in my work for planning projects to help people get into the field :)

Could you point me to the alternative model that you mentioned in the limitations?

Hi! @Tessa might have time to write up the alternative model. I don't want to put pressure on them to do so. However, the only thing I can share is:

Thank you! :)

Thank you for writing this! As someone interested in exploring opportunities in biosecurity, I found it very helpful.

I appreciate your feedback! Glad you found it helpful.