TLDR

- Healthy Futures Global is a new global health charity originating from CE’s incubation program trying to prevent mother-to-child transmission of syphilis, founded by Keyur Doolabh (medical doctor with research experience) and Nils Voelker (M Sc in health economics and former strategy consultant)

- Healthy Futures’ strategy is to elevate syphilis screening rates in antenatal clinics to the high levels of HIV screening rates by replacing HIV-only tests with a dual HIV/syphilis test

- Keyur and Nils are currently exploring potential pilot countries, and will be in the Philippines and Tanzania soon - they invite you to subscribe to their newsletter and to reach out to volunteer, especially if you are in the Philippines or Tanzania or could connect us to people there

I. Introduction: Healthy Futures Global and its Origins

Keyur and Nils are excited to announce the launch of Healthy Futures Global, a new organisation originating from Charity Entrepreneurship's latest incubation programme, dedicated to making a positive impact on global health.

Healthy Futures’ mission is to improve maternal and newborn health by focusing on the elimination of congenital syphilis, a preventable but devastating disease that affects millions of families worldwide.

II. The Problem: Congenital Syphilis' Global Impact

Syphilis in pregnancy is a pressing global health issue. It causes approximately 60,000 newborn deaths and 140,000 (almost 10% of global) stillbirths annually, contributing up to 50% of all stillbirths in some regions (1, 2, 3, 4).

Antenatal syphilis also causes lifelong disabilities for many surviving children, often going unaddressed in many countries. This disability can include cognitive impairment, vision and hearing deficits, bone deformity, and liver dysfunction. If a pregnant woman has syphilis, her child has a 12% chance of neonatal death, 16% chance of stillbirth, and 25% chance of disability (5).

III. The Solution: Test and Treat Strategy

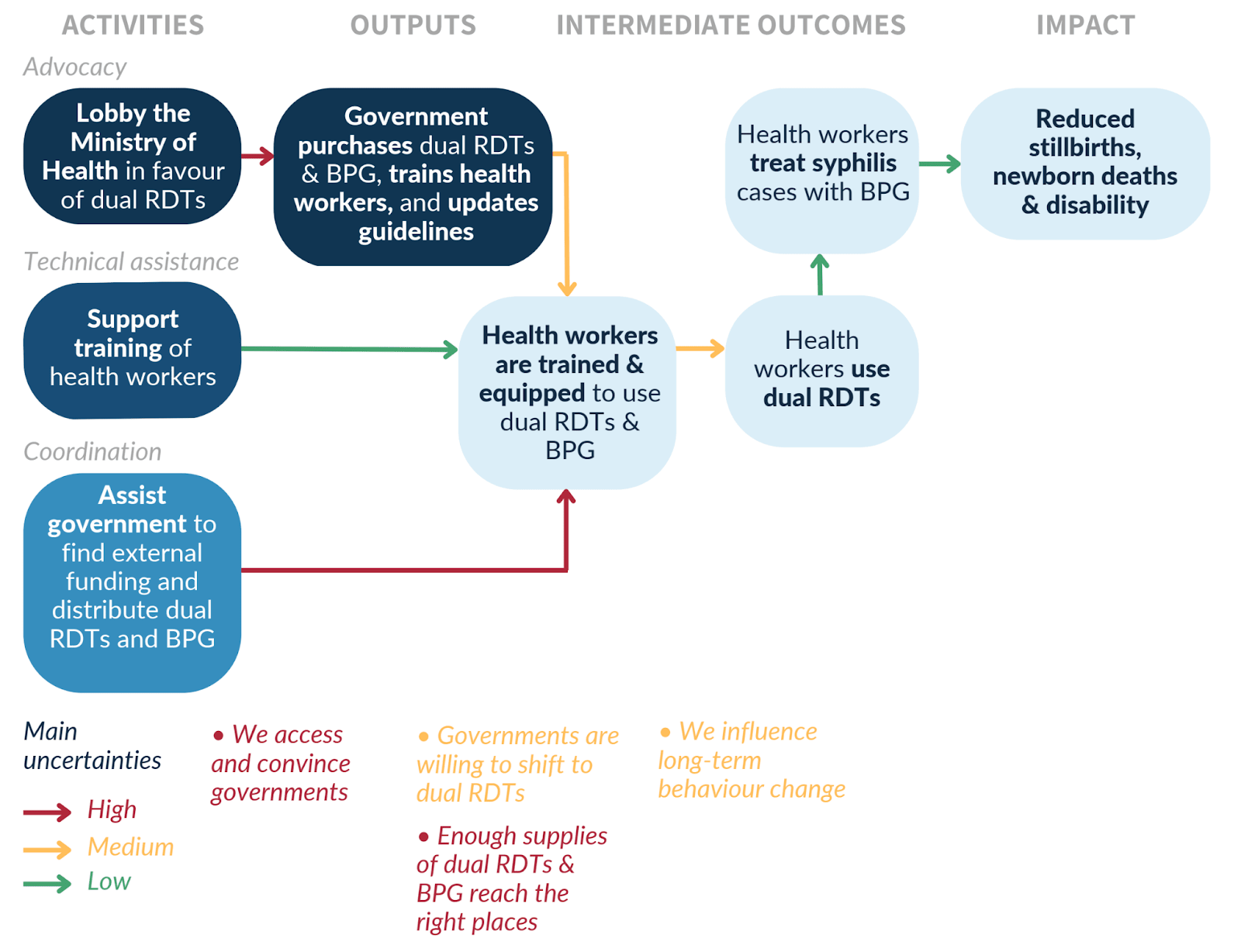

The theory of change (below) is a hybrid between direct intervention, technical assistance and policy work. It involves lobbying governments for policy support, and supporting governments, local NGOs and antenatal clinics to roll out dual HIV/Syphilis tests.

The key components of the approach involve rapid testing (RDTs) during antenatal care and immediate treatment with antibiotics (BPG) for positive cases.

The main strengths of Healthy Futures are:

- Cost effectiveness: The strategy has the potential to cost-effectively save lives, prevent disabilities, and reduce the burden on health systems. Our analysis gives us an expected value of $2,400 per life saved and ~10x the cost-effectiveness of direct cash transfers. The medical evidence for positive effects of treating the pregnant woman and her baby is strong (6).

- Monitoring and evaluation: The direct nature of this intervention offers quick feedback loops, allowing us to re-evaluate our strategy accordingly.

- Track record: Keyur is a medical doctor and Nils brings a background of consulting for pharmaceutical companies and global health organisations. Their backgrounds are a good fit for this type of intervention.

- Organisational fuel: Healthy Futures benefits from ongoing mentoring from Charity Entrepreneurship and previously incubated charities.

IV. Challenges, Risks and Mitigation

The challenges Healthy Futures plans to address are (ranked according to severity x likelihood of occurring - highest on top):

Implementational challenges:

- Sustainability: The long-term success and cost-effectiveness of this intervention depend on governments making the necessary changes in the health care system and establishing mechanisms for sustainable change. -> Healthy Futures will focus on engaging with national, regional and local governments to ensure change is initiated and sustained at all levels.

- Data availability: Publicly available data reporting in low and middle income countries on sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis is often low quality. -> The co-founders plan to connect with independent researchers, research institutions, global and local NGOs, and the ministries of health to obtain or generate higher quality data.

- Local trust: Healthy Futures will be operating in foreign countries and will face unknown unknowns, such as cultural barriers and communication challenges. -> Healthy Futures prioritises meeting and collaborating with local organisations.

- Supply chain: Penicillin requires a cold chain and has historically been prone to stock-outs. Medical staff may be hesitant to be retrained on dual tests, e.g. due to competing priorities and lack of incentives to improve standard of care. -> Healthy Futures will collect data on stock-outs and weak links of the supply chain, and closely work with health care providers to understand and adapt to their context.

Ethical considerations/challenges:

- Counterfactual impact: This intervention is fairly likely to occur even without us eventually (in some countries expected within the next 5-10). Our counterfactual impact mostly stems from implementing it earlier than it would have been implemented without us. -> Healthy Futures needs to act fast, and is open to change course or cancel operations if re-evaluation meetings point to this conclusion.

- Ethics: The moral value of reducing stillbirths and newborn deaths can be questionable from certain ethical points of view. -> Healthy Futures will follow an approach of discounting DALYs for those moral considerations, informed by GiveWell’s methodology (7).

V. One-Year Plan: Pilot Projects in the Philippines and Tanzania

Year 1 focuses on identifying the right pilot country and preparing a country-wide roll-out of dual tests. The countries were evaluated by primarily looking at the number of preventable antenatal syphilis cases, the gap between HIV and syphilis testing in pregnancy, capability of the country's health system, policies supporting dual tests, and lack of other organisations working on antenatal syphilis.

The Philippines and Tanzania seem most promising. In order to confirm the scale, tractability and neglectedness of antenatal syphilis testing, the co-founders will visit and try to meet with local and global NGOs, and political and health care leaders in the Philippines (24 May to 16 June) and Tanzania (19 June to 17 July).

Within the first year of operations the co-founders expect to prevent around 7 newborn deaths and stillbirths, and over 2,000 within 5 years.

VI. Call to Action

- Support us!

- Remotely: We are searching for volunteers on operational tasks, such as legal, finance, and website management. If you’re interested, please fill out this form (5min).

- In-country: We are searching for people that can help us navigate on the ground in the Philippines (May 24th to June 16th) and Tanzania (June 19th to July 17th), e.g. translating, connecting us with people. If you’re interested, please fill out this form (5min).

- Stay informed! Please sign up to our newsletter via our website here.

Together, we can make a difference in the lives of mothers and newborns worldwide. Join us on this journey to create more healthy futures.

VII. References

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0211720 (2019)

- https://data.unicef.org/resources/a-neglected-tragedy-stillbirth-estimates-report/#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20an%20estimated%201.9,stillbirths%20per%201%2C000%20total%20births. (2019)

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/stillbirth#tab=tab_2 (2019)

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3893926/ (2014)

- https://www.scielosp.org/article/bwho/2013.v91n3/217-226/ (2013)

- https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S9 (2011)

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hOQf6Ug1WpoicMyFDGoqH7tmf3Njjc15Z1DGERaTbnI/edit# (2020)