This is a linkpost for https://www.rhyslindmark.com/ftx-future-fund/.

Warning: Lots of napkin math below. Lending y'all an Idea That Is Not Yet Fully Formed™. But wanted to share so you get a rough map of longtermist funding.

My org is writing a grant application for FTX Future Fund's first grant round. (You should too! Apply by March 21.)

As part of that, I wanted to research how important FTX Future Fund is for the longtermist ecosystem more generally.

In summary: It's quite important! Let's learn why.

I. EA Funding Right Now

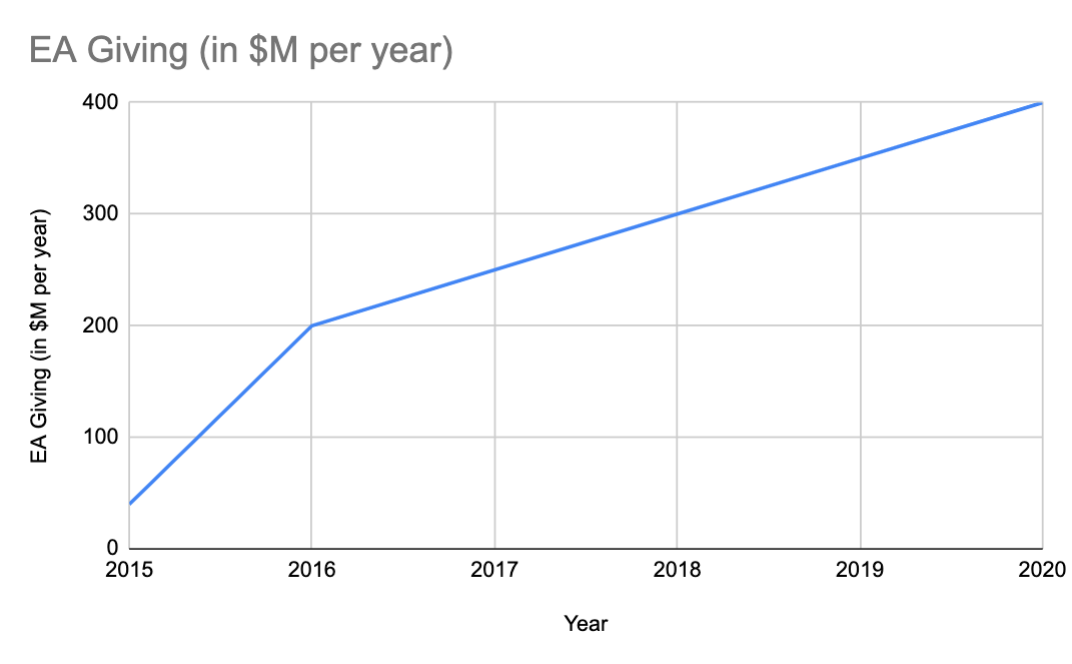

First, let's look at EA funding over time.

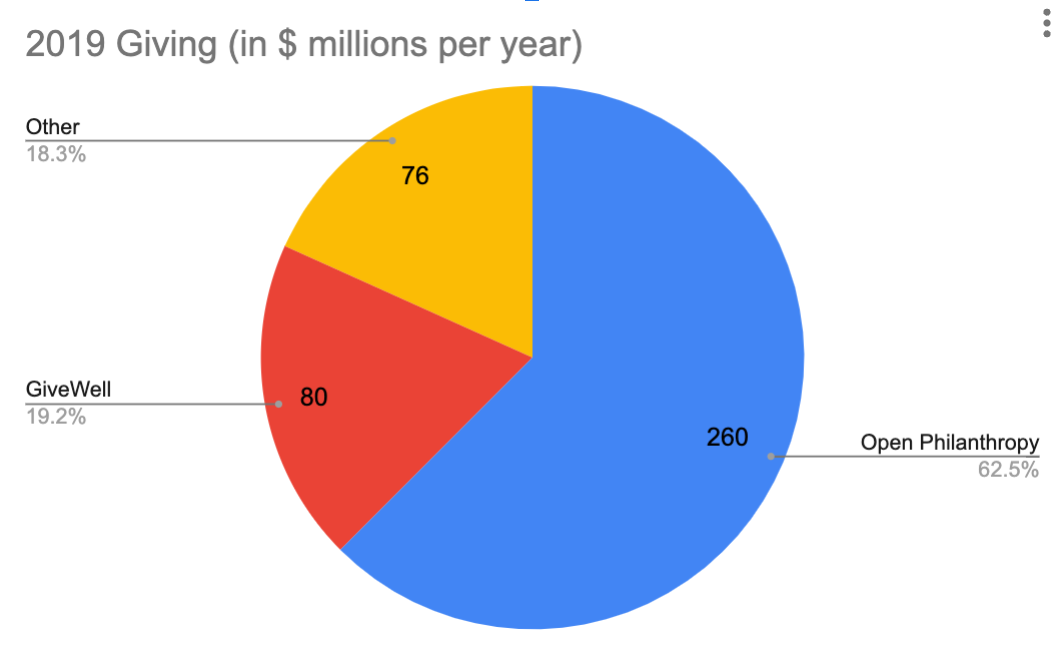

Of all Effective Altruist (EA) funding, 20% comes from GiveWell and 60% comes from Open Philanthropy (Open Phil).

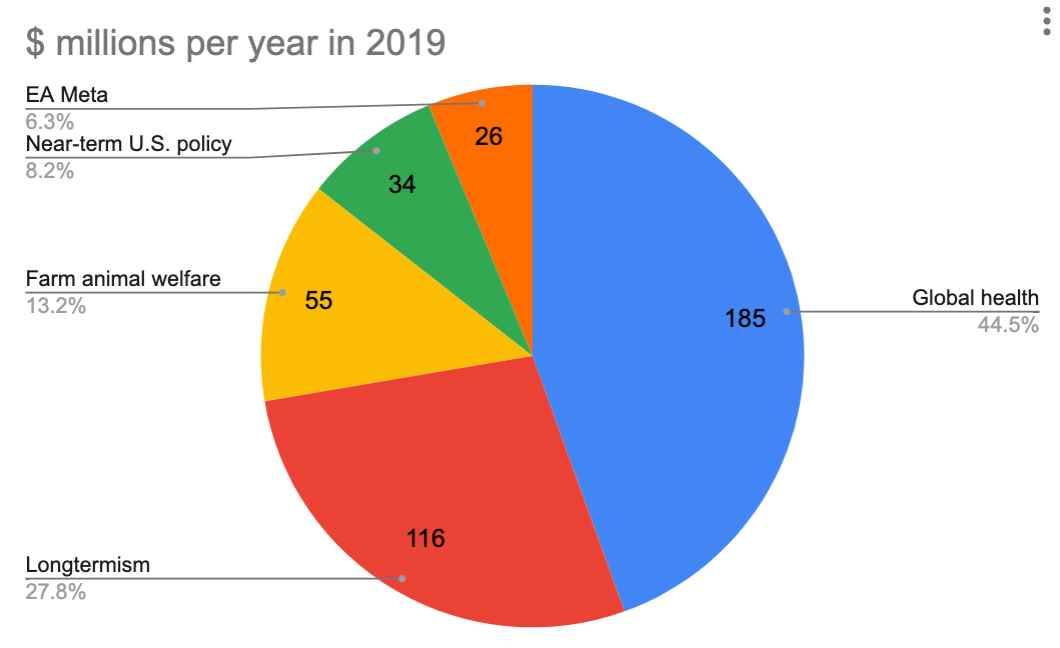

In 2019, here's how much each org processed:

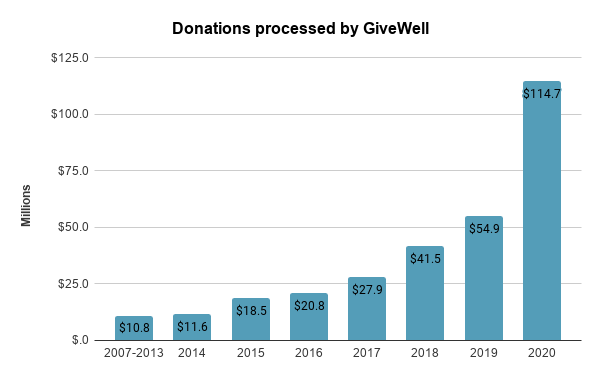

What about GiveWell's giving over time? Their graph is below.

They processed only $2M per year in the 2000s, then started to grow from $10M to $100M per year throughout the 2010s.

https://blog.givewell.org/2021/05/11/early-signs-show-that-you-gave-more-in-2020-than-2019-thank-you/ (this doesn't include Open Phil)

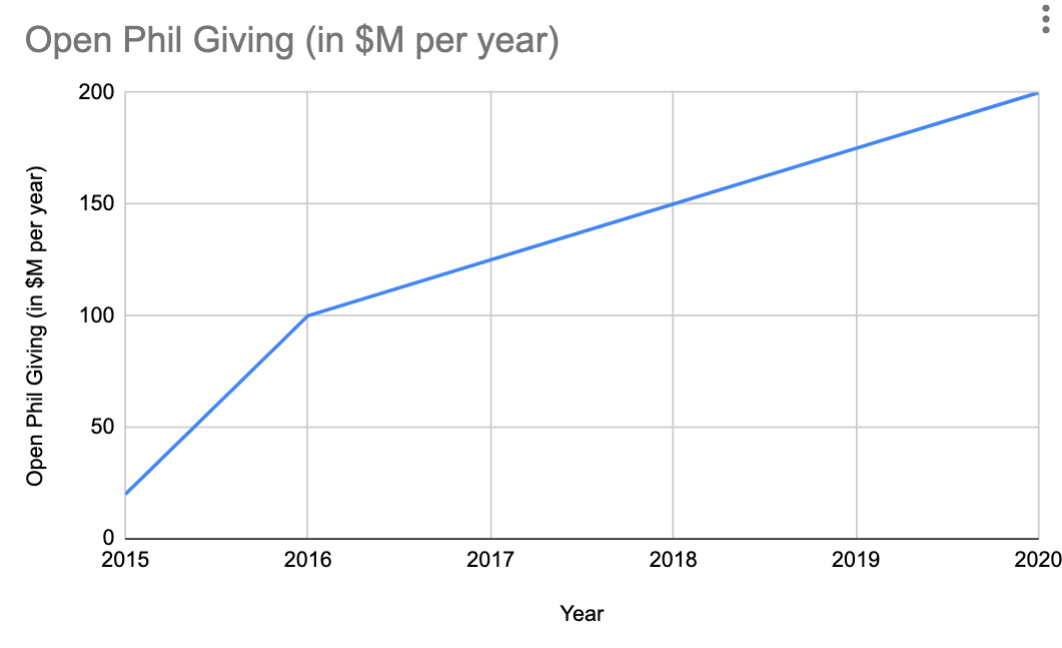

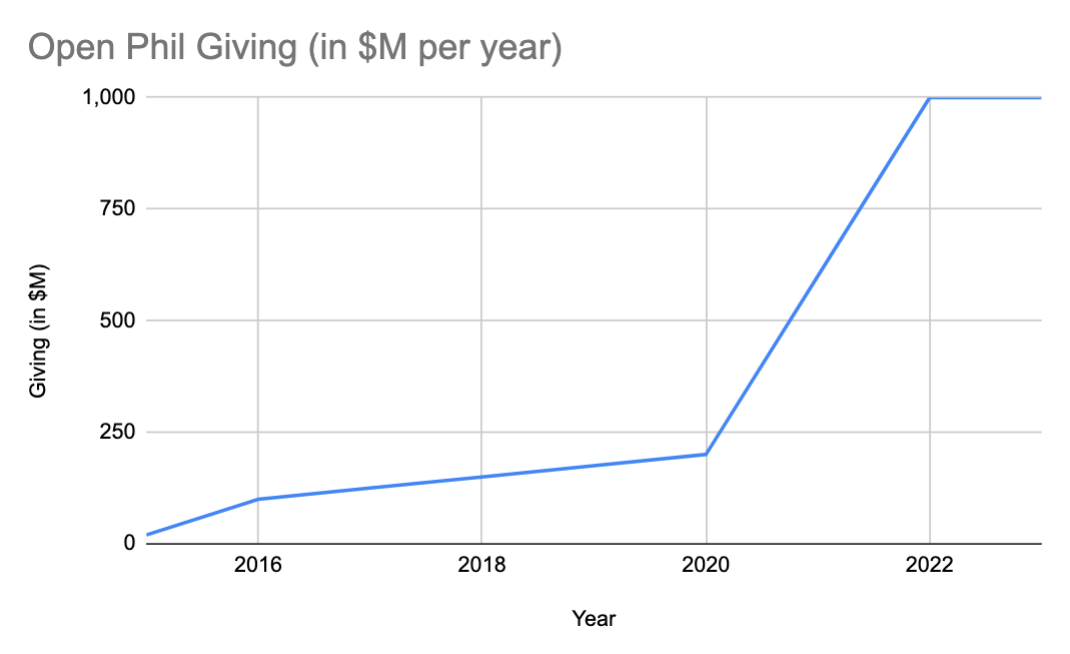

And here's Open Phil's estimate of how much they've given per year:

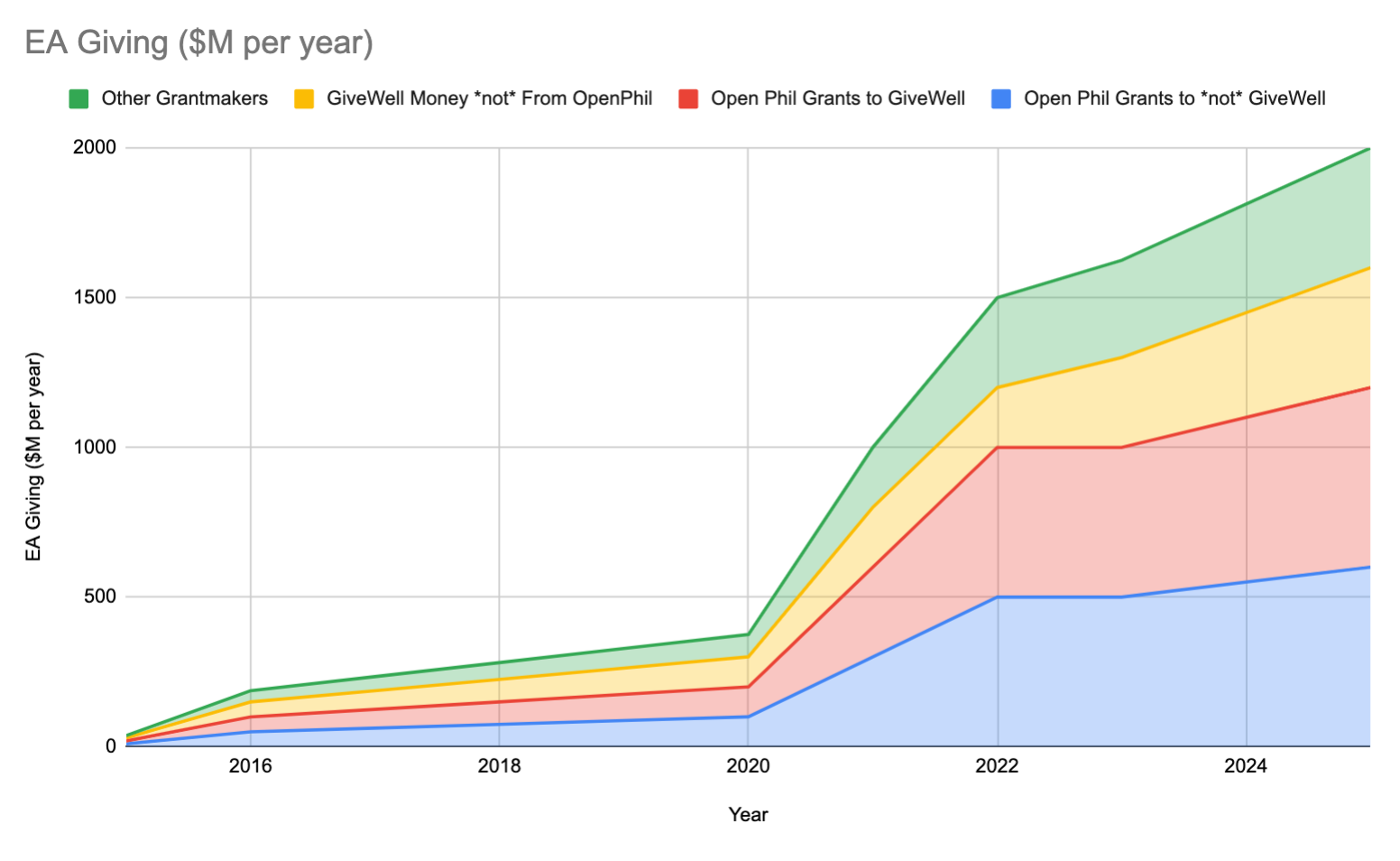

So, taking GiveWell and Open Phil together, here's how much EA money has been given per year throughout the 2020s:

$400M, not bad.

But this is actually going to ramp up a bunch in the coming few years. Open Phil only regranted $100M to GiveWell in 2020, but they plan to grant GiveWell $300M in 2021, $500M in 2022, and $500M again in 2023.

So how much will Open Phil be granting total?

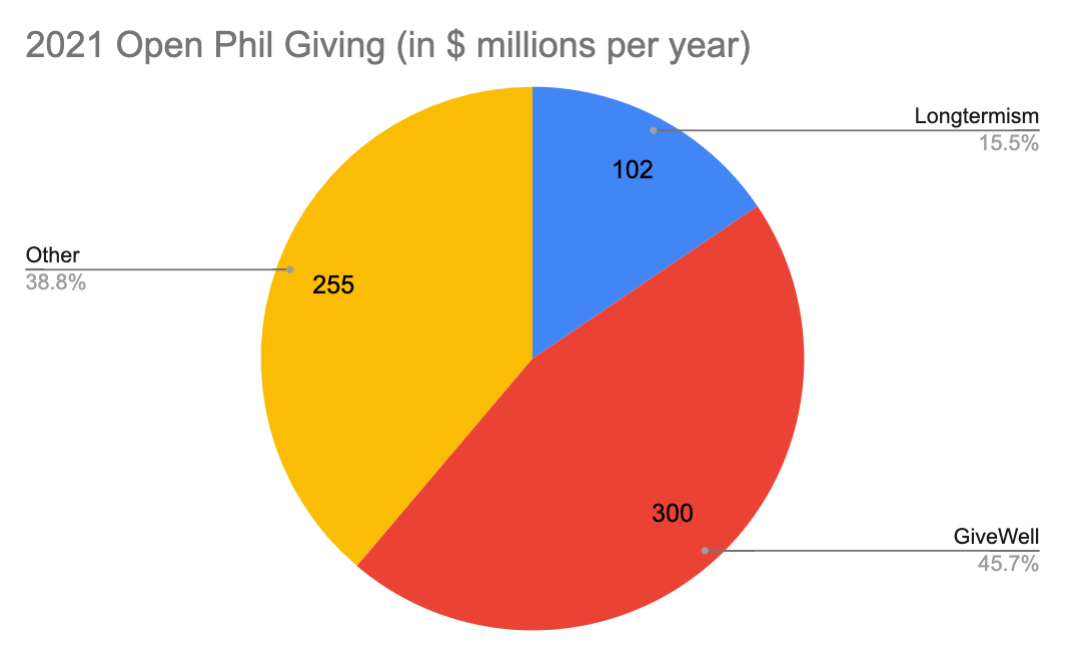

Based on 2021 data, GiveWell granting is roughly 50% of Open Phil's budget:

So by increasing their 2022/2023 GiveWell giving to $500M, we'd roughly expect Open Phil to give $1B by that time:

GiveWell itself wants to direct $1B by 2025. If we take all of these together:

- $$ from Open Phil to GiveWell

- $$ from Open Phil to not GiveWell

- $$ to GiveWell from not Open Phil

- Other Grantmaking

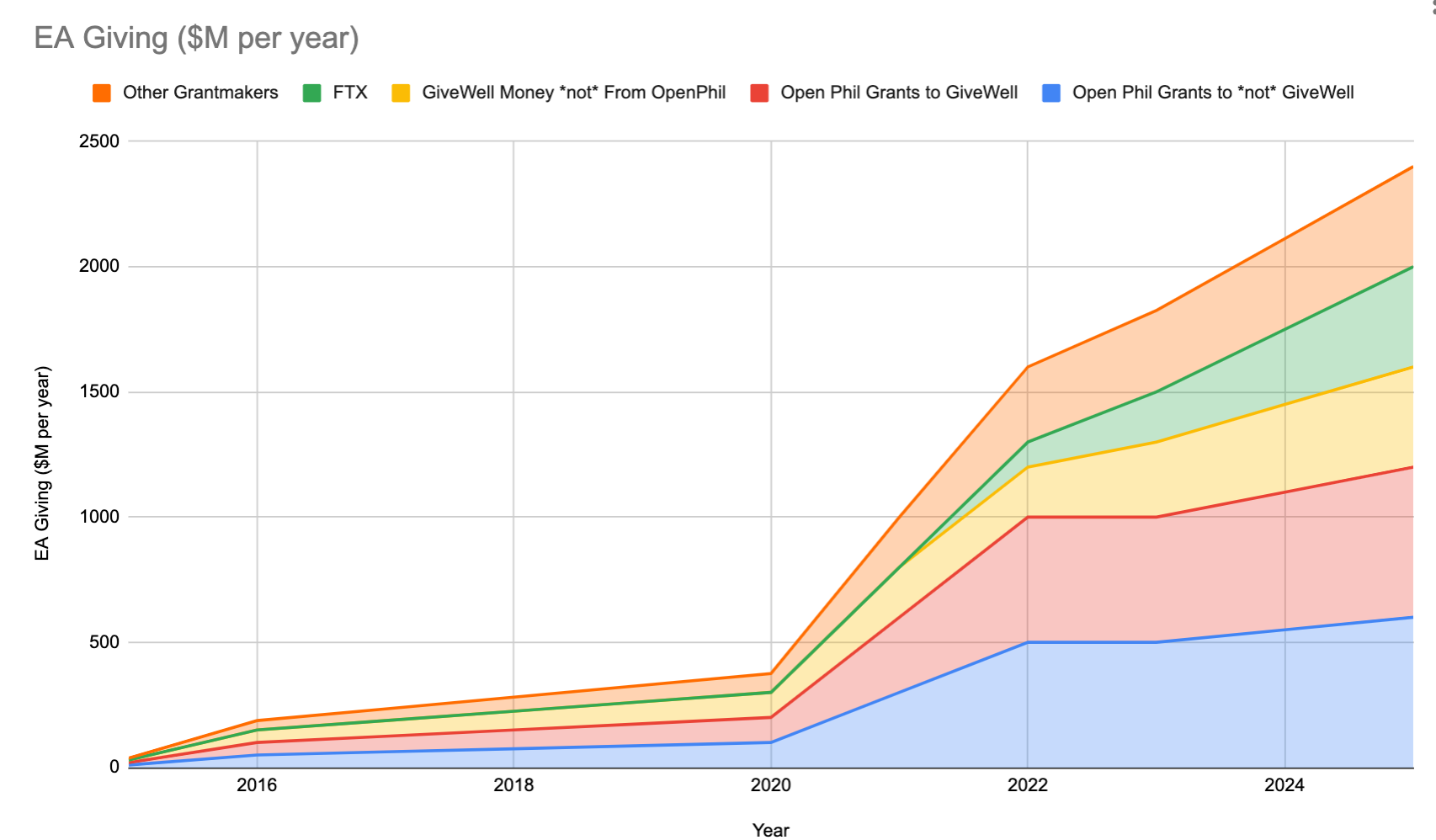

The growth of EA giving into 2025 looks like this:

In other words, we're just at the start of EA funders giving a lot more money.

Still, most of EA granting lies with Open Phil and GiveWell. And much of that is still in Global Health.

...Until now!

II. FTX Future Fund and Longtermism

Meanwhile, Sam Bankman-Fried has been making magic internet money.

He's starting to give it back, mostly towards longtermism. How much of an impact is it having?

We can start by looking at how much money is in longtermism now.

Let's start with Ben Todd's excellent overview of 2019 EA granting categories, which I've slightly modified.

As you can see, longtermism (in red) is roughly 30% of all EA giving. In 2021, it was roughly 15% of Open Phil giving.

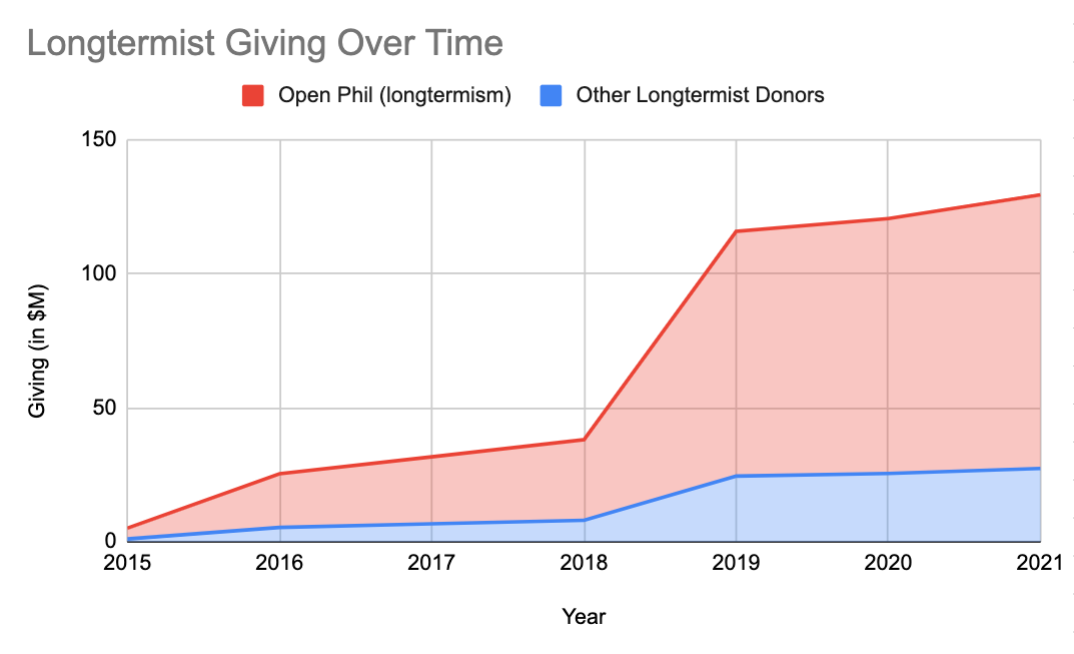

So, assuming roughly 20% of Open Phil's giving is longtermist, and assuming other longtermist donors are roughly 20% of Open Phil's longtermist giving, here's what longtermist giving looks like until now:

This is good! It's a reflection of the EA ecosystem accounting for the idea that ~future lives matter.

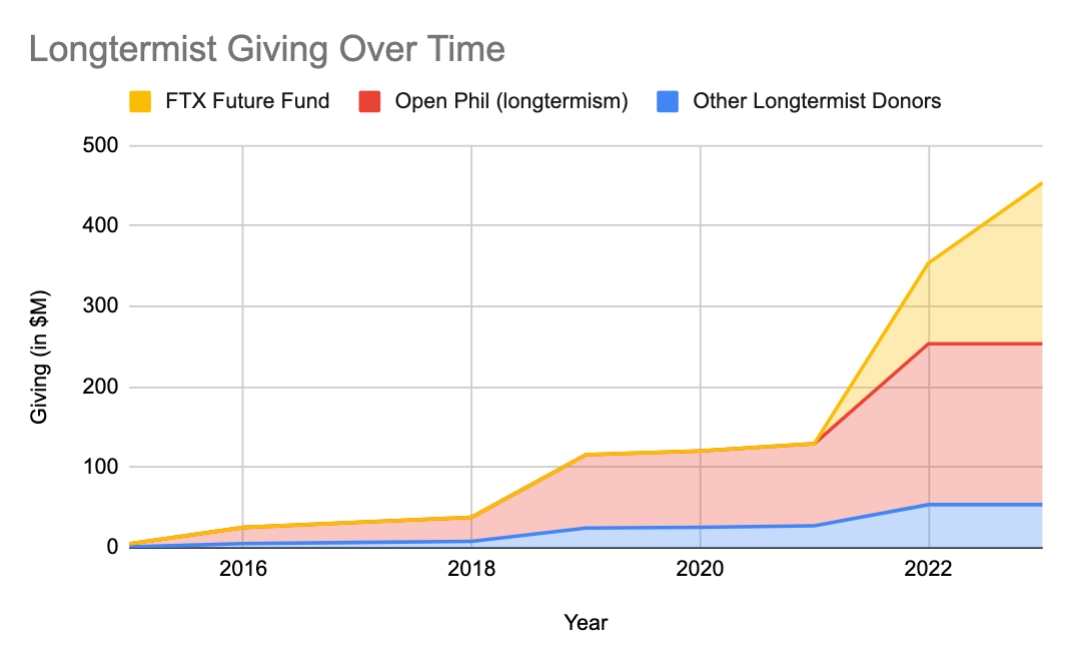

But FTX Future Fund is about to drastically increase it even more. They're trying to give $100M in 2022 alone. Here's what the graph will look like going forward:

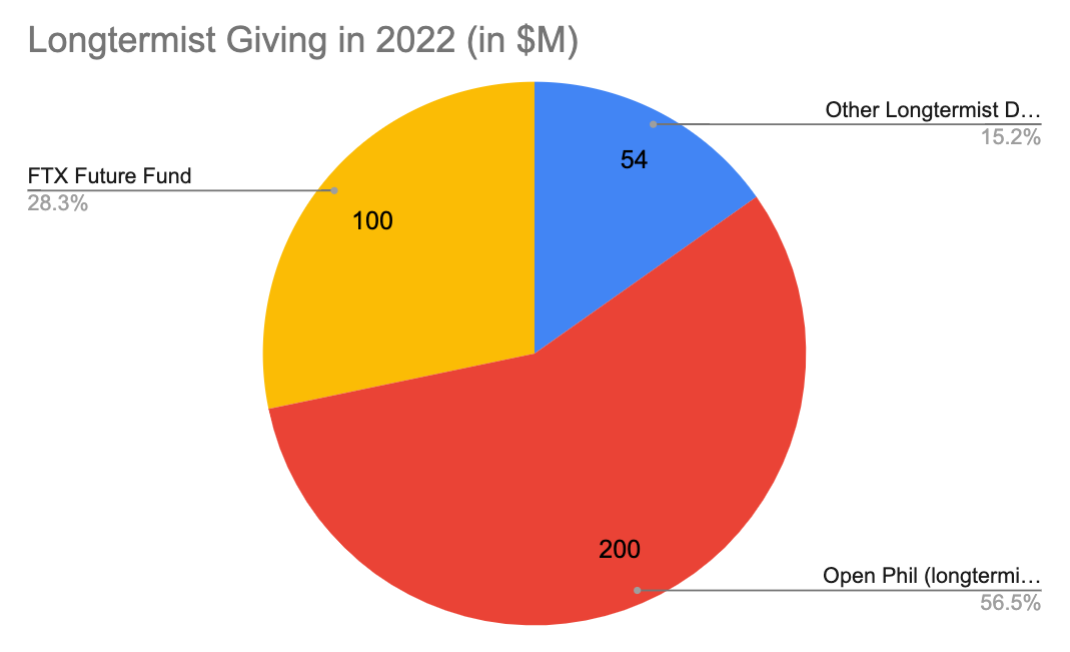

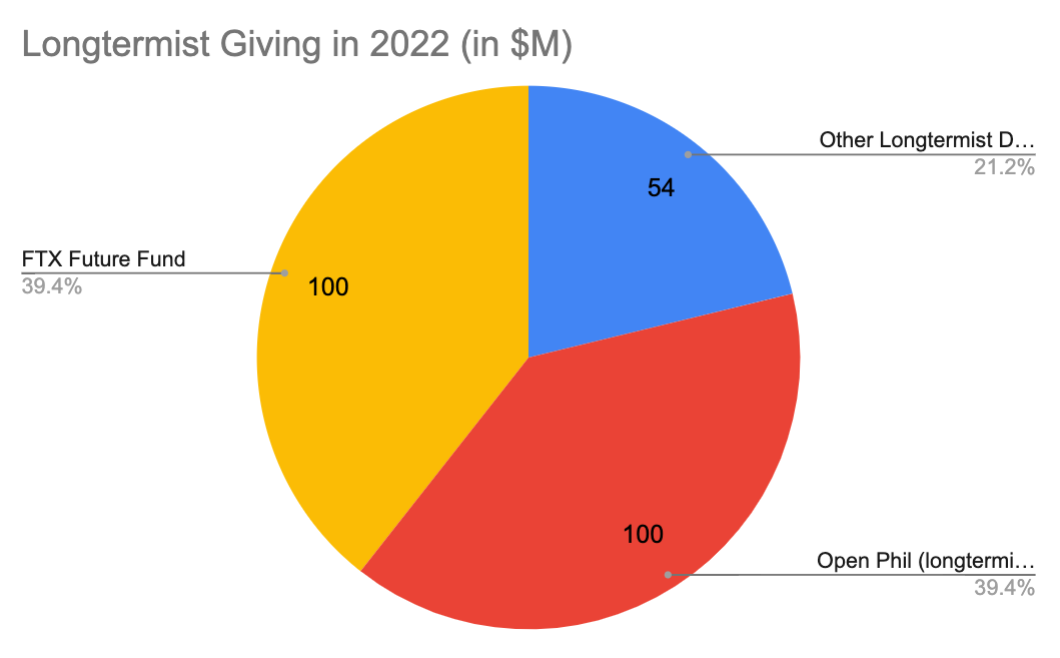

That's a big yellow jump! It makes longtermist giving look like this for 2022:

But even this assumes that Open Phil is going to 2x their longtermist grantmaking in a similar fashion as they're pumping money into GiveWell.

If they keep their longtermist grantmaking at current levels, around $100M, the 2022 pie chart looks like this:

So, yes, the FTX Future Fund is a big deal for the longtermist funding ecosystem.

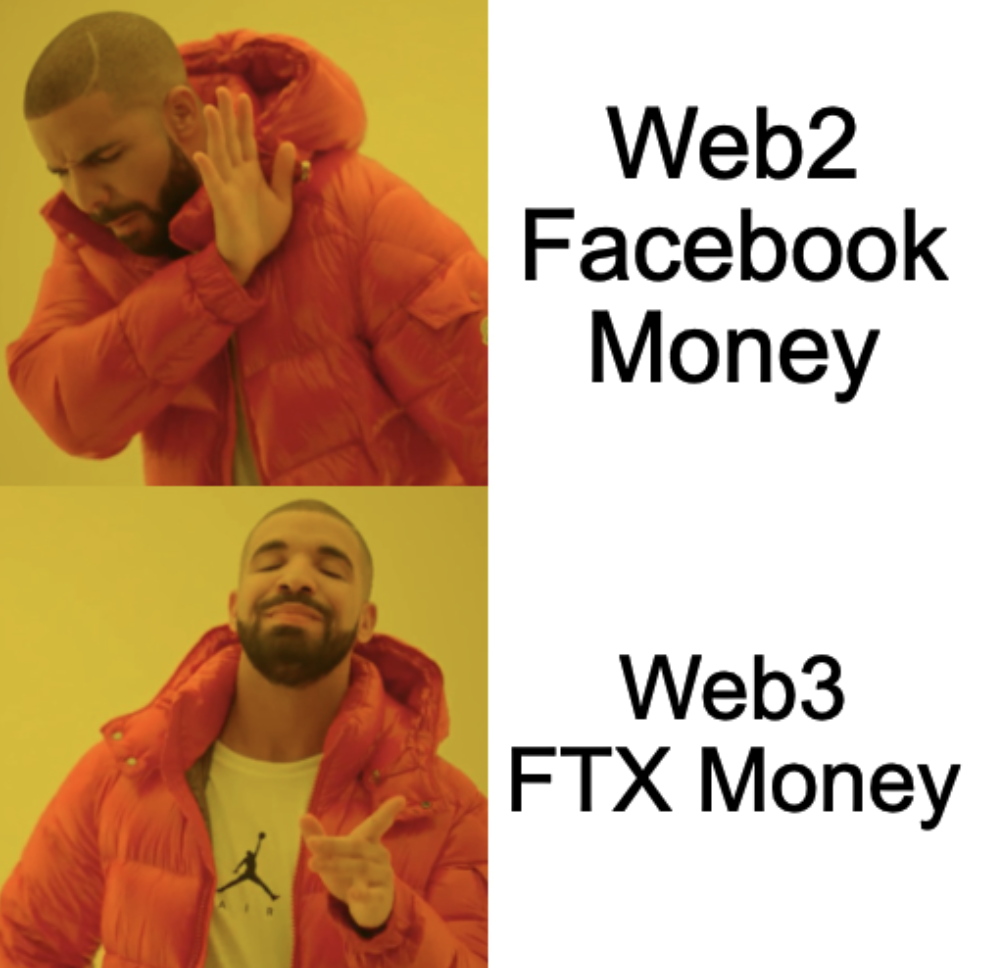

The EA funding ecosystem has had a shift. Dustin Moskovitz was a Web2 Facebook Money. SBF is Web3 FTX Money.

This means we should add a new player, FTX, (in green!) to our overall EA giving graph below.

Hope this helps give context to FTX's longtermist grantmaking.

Thanks for reading and don't forget to apply for that sweet sweet cash from FTX Future Fund by March 21.

Notes:

- Not quite sure why some numbers don't add up. 1) Ben Todd averaged 2017-2019 to get $260M. I can't quite tell how much Open Phil themselves say they gave in 2019. They just say "over $200M". 2) The graph here shows that Give Well raised $91M from Open Phil in 2020. But then Open Phil says they granted $100M. I'm working with public data and doing napkin math so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

- For more on why Open Phil is giving more to Give Well, see this post. Although at the top they emphasize: This post is unusually technical relative to our others, and we expect it may make sense for most of our usual blog readers to skip it. 😂

- As a reminder, other big crypto EA funders include Vitalik and Ben Delo.

This format is amazing. More please.

+1 -- love it Rhys; more memes pls

Do we know how much impact Sam Bankman-Fried‘s personal philosophy is going to have on FTX’s grant-making choices? This is a lot of financial power for a single organization to have, so I expect the makeup of the core team to have an outsized effect on the rest of the movement.

Valid question!

This appeals strongly to Millennials and Zoomers. Love it. Also, still a format that brings the message across. Thanks!

Awesome post. I'd just add that you've reported a lower bound. Per https://ftxfuturefund.org/announcing-the-future-fund: