My current working theory is that one of the worst things someone with a big project can do is to make that project feel extremely important. (This is doubly worse for someone with ADHD.) The more important the project, the more daunting it becomes, and the less it gets worked on.

When a project becomes ultra important, it tends to get in its own way.

The worst scenario is when someone believes that the project is their "one and only" "personal mission". ("This is my magnum opus." "This is my big project." "This is the one to shape my career." etc, etc, etc.)

For people who struggle with the importance-avoidance effect, they tend to follow this pattern:

The more important they make my project out to be, the less they get it done, and the more they procrastinate on it.

Maybe you're the sort of person who tends to think about what the world's most important problems are and wants to contribute to an important cause. (Cough, cough, EA.) Maybe you have a large project or writing in mind, awaiting action.

Effects

See if any of this sound familiar:

The more emphasized and extreme the value/importance of a project becomes, ...

- the more likely we are to procrastinate

- the less likely we are to prioritize it

- the less we get done

- the more it gets in its own way

- the more motivation we believe we need

- the more likely we are to expect perfection

- the more time, attention, dedication, and effort we believe is required

- the more overwhelming, difficult, and daunting it feels

- the more severe, complicated, and complex it appears

- the less clear the vision becomes

- the less clarity we have on what to do and how to do it

- the less capable and confident we feel

- the less we believe we can "get it right" the first time

- the more afraid and anxious we get

- the more negative emotions we associate with it

- the more likely we are to avoid and neglect it

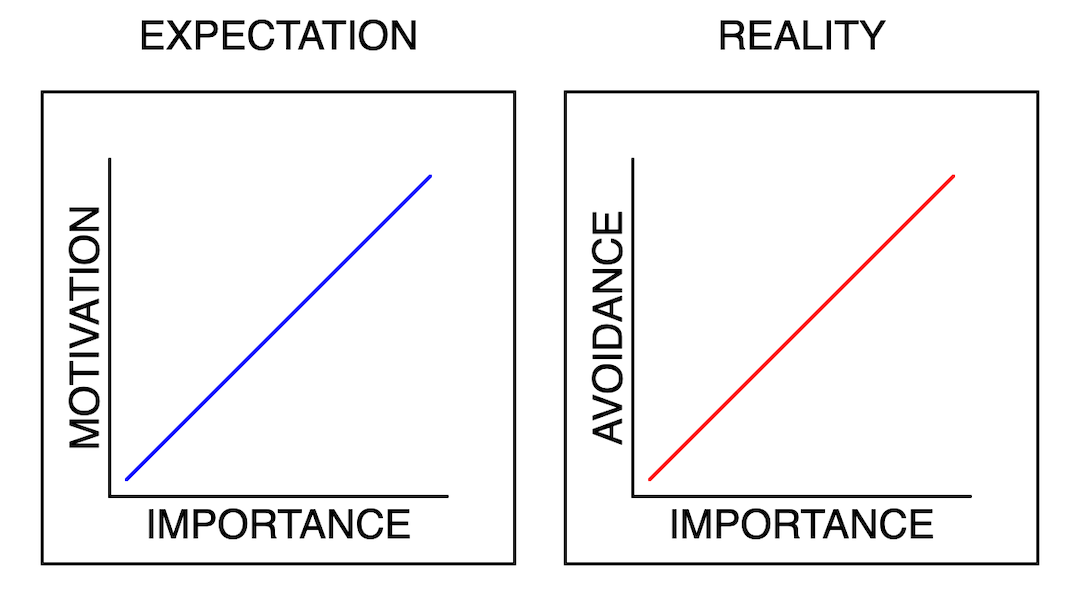

Expectation vs Reality

We like to think that: the more we emphasize the importance (and value) of something, the more motivated we will become. Yet often the truth is: the more we emphasize the importance (and value) of something, the more likely we are to avoid it.

Definition

The Importance-Avoidance Effect is a cognitive bias that causes people to procrastinate and avoid prioritizing something perceived as extremely important.

Side tangent about naming

On the streets, this cognitive bias effect also goes by the nickname, "The Fainting Goat Effect", so it can fit in with its homies, "The Ostrich Effect" and "The Meerkat Effect", who obviously have cool animal names. And besides trying to take after the ostrich effect's cool name, the fainting goat effect has been tryna jock the ostrich effect's style too by following similar patterns…

The ostrich effect is a cognitive bias that causes people to avoid information perceived as potentially unpleasant. It is believed to be the result of the conflict between what our rational mind knows to be important and what our emotional mind anticipates will be painful.

The importance-avoidance effect (AKA the fainting goat effect) isn't about avoiding information, it is instead about avoiding initiative. And instead of a perception of unpleasantness, it's a perception of extreme importance (which is often accompanied by a perceived need for perfection, which in turn may actually result in feelings of negative emotions, distress, and unpleasantness).

So while the ostrich buries its head when unpleasantness is afoot, the fainting goat is paralyzed when faced with something overwhelming.

Here's another way of thinking about this…

Backfire

When something has the potential to be ultra important, it is usually so overwhelming to contemplate the severity and complexity of it that it is often easier to just avoid and ignore it entirely.

One of the biggest issues with this is that we all tend to assume that emphasizing the importance of something will increase the likelihood that we will prioritize it, whereas this effect shows that this can backfire.

By trying to reinforce the value of something to build the most convincing case of why that thing is important, we think we're going to effectively motivate even more. However, this effect can lead to more procrastination and less effective prioritization.

Acknowledgement

(This of course assumes that the person already believes that the thing in question is at least important/valuable enough to prioritize in the first place. If someone truly doesn't understand the value of something nor its importance, then there ought to be an intervention of this kind of motivation that educates them on the value and importance. This discussion is not dealing with that scenario.)

Summary by Ting Jiang

In the Clearer Thinking podcast episode with Ting Jiang, she explains how this creates a two-part heuristic that leads to avoidance:

[Behavior Change and Interpersonal Connection with Ting Jiang | Spotify @ 8:24 – 10:00]

"The more you emphasize the importance of an action, the more likely someone is going to procrastinate on it and actually decide not to do it.

There's actually lower uptake with the emphasis of importance. (And this is related to the heuristic and bias of the ostrich effect.) So when you think something is important, first of all you have a heuristic of: 'Oh, maybe this deserves more attention. Let me spend more time on it later.'

But on the other hand, because it's important, if you don't have a clear idea of what to do and have enough confidence that you'll arrive at a good decision, you're also afraid of it. And that negative emotion pushes it off even more, or you will try to avoid it.

And so these two coming together makes it that actually emphasizing the importance of improving the attitude or trying to motivate someone even more, sometimes can even backfire — not only that it doesn't work well but not realizing that: oftentimes it's not about motivating people further but it's about getting people to implement their intention successfully."

She effectively explains how we often assume that the solution to a failure to prioritize something is to try to motivate even more by emphasizing the value and importance of that thing.

There are a few key ideas she touched on that I want to highlight:

Conditions

Time, focus, attention, and deep work

When we're faced with something perceived as extremely important, we often believe that it deserves more time and attention than we can give to it right now. This leads us to believe that this task or project at hand will require extreme dedication and prioritization. We start to tell ourselves that we will need two times the amount of time we may have projected before. So suddenly the work-time required just doubled and we are hard pressed to find any time in our schedules to give that level of commitment and dedication. (This is also compounded by the belief that extremely important things deserve more perfection. [More on that later.]) In sum, we start to believe that this task or project will need a degree of attention and time that we cannot muster in normal circumstances. As the importance becomes more extreme so do the conditions of engagement. An extremely important project requires extremely perfect circumstances. And in the end, the extreme conditions may never be met, creating a perpetual avoidance and procrastination.

Clarity, confidence, and self-efficacy

Two of the necessary conditions we need in order to work on something extremely important are: (1) a clear idea and vision of what to do and (2) enough self-efficacy and self-confidence. When both or either of those conditions are not met, we usually feel afraid. And that fear creates a negative emotional response to this extremely important thing, which then further pushes it away. Fortunately, if we can recognize which of these conditions is not met, we can probably work on them, because a lack of clarity or vision and a lack of efficacy or confidence are both problems that are certainly solvable. However, the problem exacerbates when the extremeness of the importance creates an extremeness of these conditions — namely, (1) the extreme complexity of a project can make it feel impossible to gain complete clarity on, and (2) the extreme value of the project can make it feel impossible to have the perfect capabilities to get it right. So the fear might manifest as: (1) "this is too complicated, confusing, and complex" or (2) "this is too difficult to attain".

Strategies

In the end, more motivation is not the solution. Instead, the solution is often about implementation strategies, such as basic behavioral change techniques to prioritize action. Usually the intention is already firmly set, but the mental framing and disposition hinders action and promotes procrastination. So the solution must address both the person's perception and the person's habits and regular routines. Sometimes the simplest solution might just involve effective reminders around a definitive schedule (e.g. setting an alarm to set aside [X] minutes). But personal perception is equally relevant here, so the person must believe that: even a minor moment of intentional dedication is enough and is worthwhile. And changing one's belief can be the trickiest part of the puzzle.

Perfection

On a final note, I want to reiterate an idea that has been personally troubling for me:

Usually, when I believe that a project is extremely important, I then also believe that that project must be perfect. Anything less than perfect will be a regretful shame.

The more important and valuable the project, the more utterly perfect it must be.

And while striving for perfection often leads to outstanding and extraordinary outcomes, a need for extreme perfection can actually just be paralyzing and create a platform of procrastination. So for me, the ideal is to do whatever is necessary to get started on a project, and that might require a rejection of perfection — I can't be perfect; I can't perform perfectly; and I cannot execute the perfect project. If I expect perfection of myself from the beginning, I may never engage with the project at all. This comes back to the concept of self-efficacy and self-confidence as well; in the frame of perfection, my capabilities will never meet the mark.

Expectations of perfection can make a project feel unattainable, especially when that project is even moderately complex and consequential. It is sometimes impossible and even detrimental to try to thoroughly analyze and evaluate all possible factors and outcomes of a project. (Trust me, this is coming from a person who puts "thoroughness" down as his #1 favorite/greatest strength.) If you must make every consideration and every potential consequence perfect, your project may never see the light of day. It's a nearly impossible task to expect of yourself (or anyone for that matter).

So what can we do?

Well, first off, there are many things we can stop doing…

- Stop trying to be perfect all the time.

- Stop trying to make a task or project perfect.

- Stop believing that everything we do is extremely important.

- Stop trying to prove ourselves as perfect and super outstanding.

- Stop trying to be the absolute best.

- Stop trying to make a task or project the absolute best.

- Stop trying to avoid feedback, exposure, and critique until the project is perfectly ready.

- Stop trying to perfectly prepare and plan every detail in advance (without ever taking any action).

- Stop trying to think too long-term with your project's roadmap, months and years in the future, when you don't have the next days and weeks outlined.

- Stop trying to make visionary ambitions that exaggerate the project's importance.

- Stop trying to constantly escalate the project's potential value.

But then I think the next best thing we can start to do is:

- If you are socially motivated, aim to live, act, and behave as if your close loved ones were your only "audience" in life.

- Aim to please them and not the entire world.

- Aim to just be perfect in their eyes, not everyone else in the world.

- Aim to be the best within that smaller, more reasonable context and only in specialized areas of your own expertise.

- Only aim to prove yourself to these few.

- If you are motivated by potential consequential social impact, start with the aspirations of positively impacting just your close loved ones at first.

- Narrow the scale and scope of your projects' and life's impact on these few, initially (in order to limit your vision and expected outcomes).

- Find ways to reduce the complexity of your project.

- Break your next steps down into bite-sized, manageable tasks that might only take up an hour or two of your time.

- If you're trying to work on a project that seemingly requires a great deal of time, then set a low bar expectation on yourself to just schedule a small amount of time on your project(s) in a recurring timeframe. (Example: set aside one hour every Tuesday and Thursday to work on it.)

- Set a (tighter than you want) deadline.

- Prioritize the next small, achievable step progressing towards your goal. (One step at a time.)

- Try "fear setting", where you outline your fears by defining them across three factors: (1) What's the worst thing that could happen in relation to that fear? (2) How might you prevent that outcome? (3) Even if that fear becomes a reality, how might you repair the situation afterwards?

- This should hopefully reduce uncertainties and build clarity and confidence.

- Feeling like you're lacking self-efficacy and self-confidence? Take time to train and improve your abilities and skills in whichever ways work best for you.

- Keep a bunch of irons in the fire (but not too many of course). Let yourself engage with a couple projects at a time, instead of just trying to exclusively dedicate yourself to a single project.

- Another idea like this is to try to make some other project in your life seem more important or the most important in an effort to your trick yourself into easing up on the project(s) where you actually want to get things done. Better yet, get someone in your life to "assign" that other project to you. (For more, see Aaron Swartz's thoughts on productivity, procrastination, and "false assignments".)

- Share the load of the project with others. Get some trusted individuals to work with you.

- Dig into your original intrinsic motivations, and don't let extrinsic motivations get in the way of their powerful influence. (Remember why you care in the first place. Enjoy the rewards your beautiful brain provides you along the entire process of your work. External rewards can sap your ability to savor the reward system within you and the inherent satisfaction it offers.)

- Take a step back and clarify your vision; then write it down somewhere you can always easily reference.

- Remember that action begets action! Get the ball rolling. Build momentum.

- Go work on your project right now and just do one single task. Onward!

- If you absolutely cannot do anything related to your project right now, then schedule time to do at least one related task in the next [36] hours. Set a reminder in your phone or mark it on your calendar.

- Every step forward makes the goal more enticing!

Essentially, most of these tips and techniques boil down to recognizing the cognitive patterns and reframing/overriding them with something more productive to prevent the avoidance and to cultivate conditions for actually getting things done.

Notes

Motivation and demotivation are tricky, nuanced things that are rather personal. One of the biggest and most rewarding challenges in life is unraveling the mysteries of your own motivation. (What makes you come alive? What stresses you out? What makes you eager and excited? What makes you feel burnt out?)

Tailor the insights you might gain from this "importance-avoidance effect" to your own understanding of your motivation. (What might be quite motivating for some people could be demotivating for others. [So blanket statements about motivation can be risky.])

Suggestions

Please add in your advice! Discuss your experiences and share what works best for you.

- Do you deal with this?

- How do you deal with this?

- Do you have any recommendations?

- What other effective strategies (techniques, tips, methods, etc) do you use?

Feedback

This is my first time writing to the Forum. (I've always wanted to get more involved, but I've never tried it before - cuz I get nervous about wanting to make a best first impression. Ironically, this post is basically a glimpse into the reasoning behind why I've never posted to the forum before.)

Please give me your thoughts, reactions, opinions, and (dare I say) critiques. (Thanks in advance! Take it easy on me 😉)

- Was this written well? Coherently?

- Does this make sense? Do you agree? Disagree?

- What's missing?

- What's excessive or doesn't need to be in here?

- Was this valuable for you?

- Would you find yourself actually remembering this and calling the situation out by this name from now on?

- What should I tag this with?

- Is this better suited for LessWrong?

Shout out and thanks to Jarred, Debbie, and Sam for listening to me, reading the first draft, giving me hecka inspiration, and helping me battle this silly effect.

This is a "crosspost" in a sense: OG version here (you can read this in sexy "dark mode" on my website 🌑👌)

Great and articulate post; thanks. Trying to follow 80,000 hours advice and my brain just plays this on repeat:

Haha, I love how you captured the vibe in such a great image! Thank you for the compliment as well :)

(Hopefully some of these strategies will help us navigate the things that truly are "most important" in our lives.)

Great article on an important and engaging topic :)

If I find myself really paralyzed on a topic I have a thought experiment I go to: What would happen if I HAD to delegate this to someone else? I pick a specific person (say, an intern at my company) and think through how I would adapt the project so that she could complete it, or at least contribute to it. Often when I've finished my thought experiment I realize that the "easy" version of the task I would delegate to someone else is exactly what I should be doing.

You might also like Aaron Schwartz's notes on productivity:

Oooo love these thoughts from Aaron Swartz! I actually hadn't read this bit from him before, yet reading it felt so familiar in that "oh snap, duh, he just put to words that kind of unspoken wisdom we've always been dancing around for probably generations" kind of way.

Thank you for sharing this! I've added some of those tips to the list here.

Thanks, I also could relate to the general pattern. For example during my PhD I really tried hard to find and work on things that seem most promising and give it my all cause I want to do it as good as I can, but this was pretty stressful and I think it noticeably decreased the fun and my ability to let simple curiosity lead my research.

This is a big one for me. Working with others on projects is usually much more fun and motivating to me.

Thank you for sharing (and reading)!

Were you able to "share the load" (so to say) in some capacity with your PhD and research?

In what ways do you effectively utilize this insight you've gained into your own social motivation? Do you tend to build teams and recruit people to help you with your projects in specific ways? How do you keep it fun and enjoyable for yourself and your friends?

I was, I started working with a colleague and I got a research assistant which really did a lot of a difference. It was very motivating to have another mind looking at the same problems and finding them interesting/challenging, plus I could focus more on the things that were most interesting to me by outsourcing some tasks.

And I think I don't have to do much else than just scheduling a meeting every two weeks or so to make it enjoyable and fun, at least for me that is all that is needed.

This is something I'm dealing with right now, so reading this was helpful. Thanks

So glad to hear it was helpful! Thanks for reading it :)

Lemme know which strategies end up being the most effective for you! I'm keen to know what works best for people. (If you couldn't tell, I'm also a person who struggles with this a great deal, so this is mostly me trying to find answers and solutions for myself as well haha.)

This really resonated with me - thanks for writing!

great article!

using an accountability system (eg accountability partner)

is another great way of handling this!

I think this post was written well and points out a potentially serious effect. I also think there is probably some validity to it—especially for some people it might be very strong—but I also like to wrinkle (or try to wrinkle) neat ideas, so I'll pose some potential objections I had while reading. In short, do you think it's possible there's a lot of correlation-causation confusion going on here? For example:

Ultimately, I'm not disputing that there probably is some degree of importance => avoidance effect, but I think it's possible to overestimate the causal relationship between importance and avoidance due to other correlated factors and observation biases.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful response! I really appreciate your ideas. I'll reply inline here:

Totally agree with this, and these things are compounding.

Most of my claim is that some people struggle with a cognitive bias effect that pushes them to avoid all of this, all together.

So you're right, it's not necessarily always the "importance" of the project that leads to avoidance or a struggle to effectively prioritize it; instead, it can be the complexity or a lack of clarity or vision that keeps the project out of arm's reach.

Curiously, I often imagined that the people who struggle with the Importance-Avoidance Effect have typically already started their project(s) to some degree. And maybe they've even mapped out an outline of steps they need to follow to complete a series of milestones. Yet despite having had some start and having some clarity and vision, they lack the initiative and prioritization. This is very similar to what you describe as struggling to "get into a rhythm." I really like that phrasing.

But anyways, there may be several compounding effects leading to a disruption in getting in rhythm. And it's not always just the "importance" alone that is to blame. But the fact is that sometime it is a major contributor, and for me, that has been something I've neglected to recognize for years! Hence why I want to bring attention to it. (We've known about our inabilities to tackle projects of great complexity. And now I'm hoping to expand on that understanding.)

That is fantastic that you are able to manage such dedication and prioritization. I'll be honest though, this is a major struggle for me and for some of my friends who I wrote this article about.

For us, no matter how little skill is required and no matter how simple the task may be, the more important it becomes, the less it gets reasonably prioritized and worked on. (I have two ongoing projects that have sat around for over a year because they only require about 10–25 hours of menial work to complete. I have tried working on them in "batches" or sessions, but those sessions are shorter and fewer and farther between... No amount emphasis on the "importance" increases motivation and prioritization. It often backfires.)

So whatever it is that you're doing that allows you to be able to muster that motivation and prioritization, please share 😄 (because I for one am not achieving that).

100% accurate. This is another compounding factor.

While this is certainly true in some cases, the people and projects I was thinking of when I wrote this would not fall into this category.

I posted this to the EA forums because the people I know who struggle with this are people who want to do these projects because of the project's importance, and because they genuinely want to do these things. They can't think of anything they would rather do. It really does become a life mission and grand purpose for them. They want to dedicate their lives to it, and they believe it is their magnum opus — their great contribution to making the world a better place.

Yet these same people find themselves needing effective strategies to "motivate" (initiate) themselves to do the hard work involved in getting these projects to fruition.

Hence why I mentioned this thought in the post:

This is very plausible! Thank you for bringing this potential bias to this discussion.

How might we further explore this? If this is a possible blindspot for me, perhaps others might be consulted to provide more perspective on this.

However, I will note that, even if there are other cases not as readily considered, it might not necessarily change the idea that, in some key cases, this might be a very real problem people face.

The exciting thing about this is that, if we properly diagnose the problem as originating from this sort of avoidance effect, then we can just try out the best implementation strategies/techniques. See where that leads 🙂

I agree. I don't want people running around "over-diagnosing" this 😅 especially when other factors might be much more significant, impactful, influential, etc.

But I also do want to bring this factor into our considerations, as I feel it can be easily overlooked and neglected. (Let's give it some of the attention it deserves for a while to see how prevalent and consequential the effect truly is.)