Katja Grace, Aug 4 2022

AI Impacts just finished collecting data from a new survey of ML researchers, as similar to the 2016 one as practical, aside from a couple of new questions that seemed too interesting not to add.

This page reports on it preliminarily, and we’ll be adding more details there. But so far, some things that might interest you:

- 37 years until a 50% chance of HLMI according to a complicated aggregate forecast (and biasedly not including data from questions about the conceptually similar Full Automation of Labor, which in 2016 prompted strikingly later estimates). This 2059 aggregate HLMI timeline has become about eight years shorter in the six years since 2016, when the aggregate prediction was 2061, or 45 years out. Note that all of these estimates are conditional on “human scientific activity continu[ing] without major negative disruption.”

- P(extremely bad outcome)=5% The median respondent believes the probability that the long-run effect of advanced AI on humanity will be “extremely bad (e.g., human extinction)” is 5%. This is the same as it was in 2016 (though Zhang et al 2022 found 2% in a similar but non-identical question). Many respondents put the chance substantially higher: 48% of respondents gave at least 10% chance of an extremely bad outcome. Though another 25% put it at 0%.

- Explicit P(doom)=5-10% The levels of badness involved in that last question seemed ambiguous in retrospect, so I added two new questions about human extinction explicitly. The median respondent’s probability of x-risk from humans failing to control AI1 was 10%, weirdly more than median chance of human extinction from AI in general2, at 5%. This might just be because different people got these questions and the median is quite near the divide between 5% and 10%. The most interesting thing here is probably that these are both very high—it seems the ‘extremely bad outcome’ numbers in the old question were not just catastrophizing merely disastrous AI outcomes.

- Support for AI safety research is up: 69% of respondents believe society should prioritize AI safety research “more” or “much more” than it is currently prioritized, up from 49% in 2016.

- The median respondent thinks there is an “about even chance” that an argument given for an intelligence explosion is broadly correct. The median respondent also believes machine intelligence will probably (60%) be “vastly better than humans at all professions” within 30 years of HLMI, and that the rate of global technological improvement will probably (80%) dramatically increase (e.g., by a factor of ten) as a result of machine intelligence within 30 years of HLMI.

- Years/probabilities framing effect persists: if you ask people for probabilities of things occurring in a fixed number of years, you get later estimates than if you ask for the number of years until a fixed probability will obtain. This looked very robust in 2016, and shows up again in the 2022 HLMI data. Looking at just the people we asked for years, the aggregate forecast is 29 years, whereas it is 46 years for those asked for probabilities. (We haven’t checked in other data or for the bigger framing effect yet.)

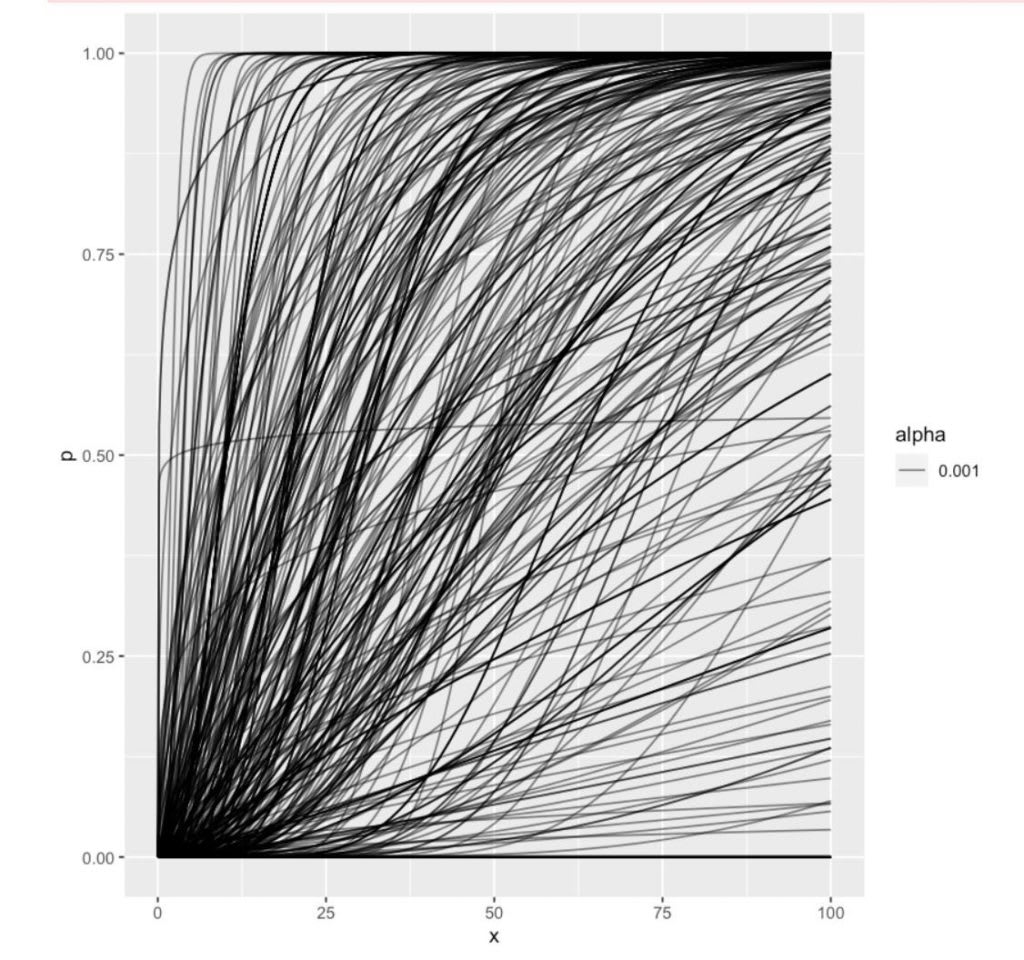

- Predictions vary a lot. Pictured below: the attempted reconstructions of people’s probabilities of HLMI over time, which feed into the aggregate number above. There are few times and few probabilities that someone doesn’t basically endorse the combination of.

- You can download the data here (slightly cleaned and anonymized) and do your own analysis. (If you do, I encourage you to share it!)

Individual inferred gamma distributions

The survey had a lot of questions (randomized between participants to make it a reasonable length for any given person), so this blog post doesn’t cover much of it. A bit more is on the page and more will be added.

Thanks to many people for help and support with this project! (Many but probably not all listed on the survey page.)

Cover image: Probably a bootstrap confidence interval around an aggregate of the above forest of inferred gamma distributions, but honestly everyone who can be sure about that sort of thing went to bed a while ago. So, one for a future update. I have more confidently held views on whether one should let uncertainty be the enemy of putting things up.

Note: most of the discussion of this is currently on LW.

Really excited to see this!

I noticed the survey featured the MIRI logo fairly prominently. Is there a way to tell whether that caused some self-selection bias?

In the post, you say "Zhang et al ran a followup survey in 2019 (published in 2022)1 however they reworded or altered many questions, including the definitions of HLMI, so much of their data is not directly comparable to that of the 2016 or 2022 surveys, especially in light of large potential for framing effects observed." Just to make sure you haven't missed this: we had the 2016 respondents who also responded to the 2019 survey receive the exact same question they were asked in 2016, including re HLMI and milestones. (I was part of the Zhang et al team)

One thing you can do is collect some demographic variables on non-respondents and see whether there is self-selection bias on those. You could then try to see if the variables that see self-selection correlate with certain answers. Baobao Zhang and Noemi Dreksler did some of this work for the 2019 survey (found in D1/page 32 here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2206.04132.pdf ).

Ah, yes, sorry I was unclear; I claim there's no good way to determine bias from the MIRI logo in particular (or the Oxford logo, or various word choices in the survey email, etc.).

Sounds right!

Heightened support for research in AI safety by AI researchers themselves seems like a requisite step for providing more resources to AI safety researchers. I'm encouraged that AI researchers are so much more favorable toward AI safety research now than in 2016, (a) because it means AI safety research is more likely to be as important as the EA community claims it is, and (b) because more pressure from academia is necessary (perhaps not sufficient, but necessary) to increase public support of AI safety research.

TL;DR: if AI researchers believe AI safety research is important, then it probably is. Also, for AI safety research to be better supported by the public, it's probably necessary for AI researchers to want it to have more support.

- Munn