This post was written jointly by Adam Braus and Markus Amalthea Magnuson, sparked by an initial conversation in San Francisco during EAG about the EA community's seeming reluctance to work on influencing governments.

This essay uses the Summa Theologica style of St. Thomas Aquinas to look at the issue of influencing governments to achieve more effective interventions than mere charity can. Many objections are probably familiar to those that have looked into policy issues from an EA perspective – this is an attempt at a rather concise outline of them and some relevant counter-arguments.

Statement: “EA should influence governments to enact more effective interventions”

Objection 1: It might be an ineffective use of resources to try to influence the government either through policy or politics. Through the lens of the ITN framework, the government represents a highly intractable system. Moreover, it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of time and funds used to e.g. lobby the government or influence elections. Therefore, EA should not spend resources trying to influence this intractable system and has done a good job so far prioritizing taking direct actions outside of government through charities and market actors.

Objection 2: Further, lobbying the government might implicate EA in partisan politics. If EA and its recommendations become identified as being partisan (of either party), we risk harming EA’s reputation and potentially alienating members of the other party from our views, and both of these would lead to less effective and impactful outcomes overall.

Objection 3: Further, governments are inefficient with their funds, spending and wasting huge amounts of money and time. Following the ITN framework, governments have low cost-effectiveness and therefore represent a low-impact intervention. Charities and market actors have more accountability and efficiency in their work which makes them more cost-effective and hence more impactful. E.g. charities distributing bed nets is a highly cost-effective way to reduce malarial infections and deaths.

Objection 4: Further, domestic policy in developed nations will have a low impact on increasing human welfare than work done in developed nations. For example, improving healthcare in the US will cost exponentially more per capita than improving healthcare in Haiti. Hence, influencing domestic governments in developed nations has a comparatively low impact, and it is more effective to deliver money directly to the place it is needed most through charities or market actors.

Objection 5: Further, it is not effective to attempt to work with or even influence corrupt governments since funds invested with those governments will not reach their beneficiaries. Also, it is not worth influencing non-corrupt governments since these are usually already serving their citizens’ best interests. In either case, funding or influencing governments have low effectiveness, and the funds and time could be better spent on charities or market actors.

On the contrary, even a cursory review of history and current affairs finds that it is governments (not charities or market actors) that are responsible for dramatically increasing access to healthcare, security, education, peace, sanitation, transportation, civil rights, hygiene, nutrition, etc. in both developing and developed nations.

We answer that, while charities and market actors might be better suited to invent, discover, and design novel solutions to people’s problems, it is governments that make those solutions accessible to the majority of people. Hence, since the goal of effective altruists is to do “the most good,” it is unavoidable for the EA community to set out to influence domestic, foreign, and international governments.

EA is “building the plane as we fly it.” So far, EA has had a low capability and capacity to influence governments. EA has focused on working with charities and market actors. As EA matures, it can develop the skills of effectively influencing governments while minimizing reputational risk. This is achievable through research, training, and recruiting. EA is an organization full of dedicated, energetic people capable of learning whatever skills and know-how they believe they will need to achieve their aims.

Reply to objection 1: While it is commonly perceived as intractable, the government is, in fact, remarkably tractable. The US government, for instance, has swung from command and control style social policies in the New Deal to a strong free market ideology in only 70 years – a historical nanosecond. This change has come about not by accident but through the deliberate actions of political actors. Every year, businesses and other lobbyists and advocacy groups intentionally and knowingly “invest” money in lobbying the government because they know they will have a predictable and measurable return. For example, a highly effective approach like this was carried out by the Koch brothers over a long time period, something that Jane Mayer investigated in detail in Dark Money. The point is not that what the Koch brothers did is good, but that it’s possible.

Reply to objection 2: EA can effectively influence policy without engaging in partisan politics. There are many proven venues of driving policy that does not engage directly in politics. EA does not need to run or support “overtly EA” political candidates and instead can take other actions, such as writing issue/policy white papers, policy proposals, and legislation, lobbying, funding candidates through super PACs, and producing editorial news media. All of these interventions are examples of how other organizations have rapidly exerted a large influence on government with minimal public partisanship and manageable reputational risk. Also, not all countries have such a polarised version of partisan politics as the US – in effect, a two-party system – so the risk of getting labelled as one thing or the other might be much smaller in countries with less polarization.

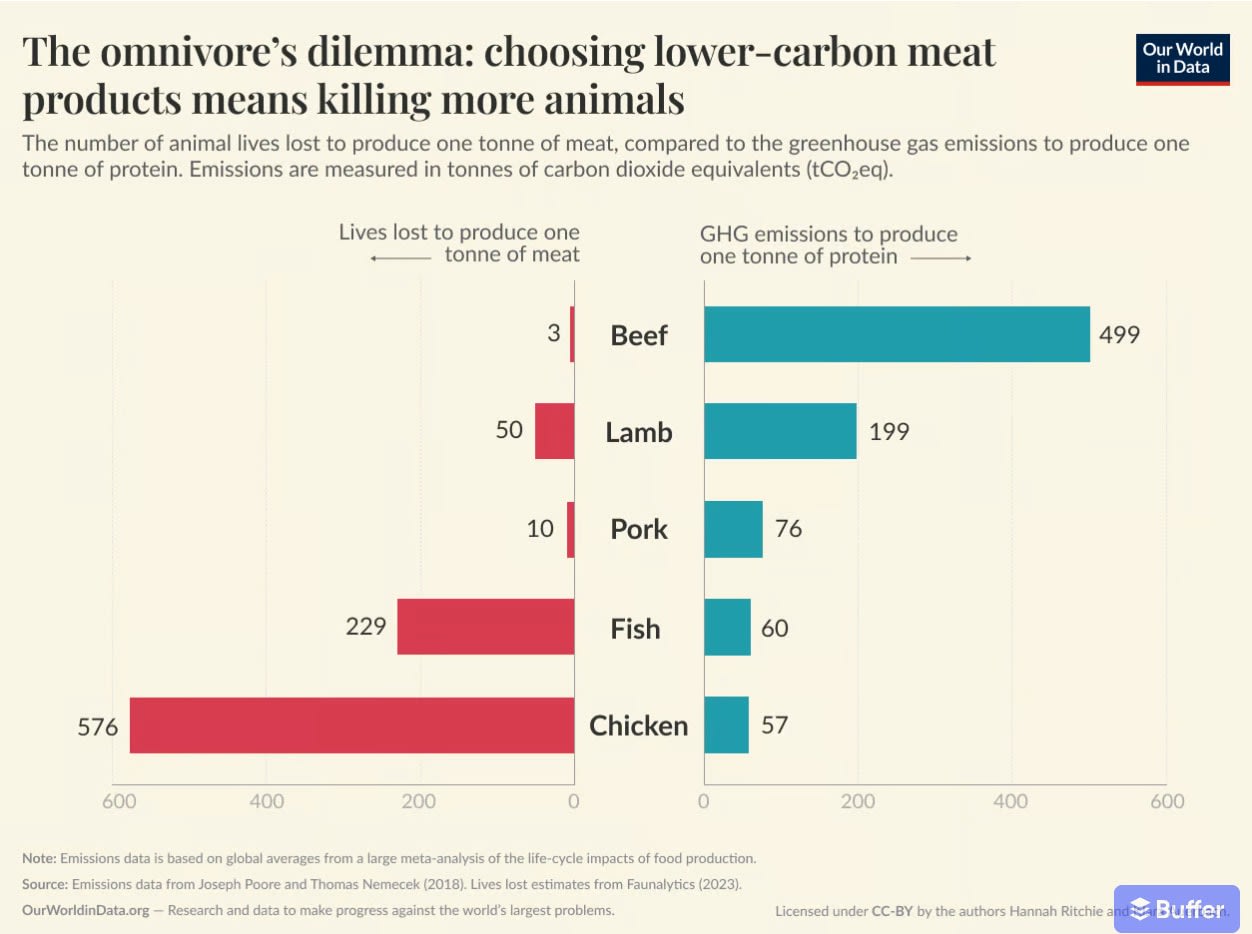

Reply to objection 3: While it is the popular perception that governments are wasteful, this is debatable. For instance, a national health insurance company run by the government, such as they have in Japan or Germany, is demonstrably over 2x more efficient (less costly with better outcomes) than a competitive market of private insurers in the US (Source: Canadian Institute of Health). Even if we can point to examples of waste, corruption, and “$500 hammers” inside of government, we must check these examples against the realities of what governments achieve every day – educating the majority of children, operating the police and military, operating enormously complex systems of public health and nutrition, building and maintaining breathtaking systems of transportation, etc. There is waste in government, but there is also gargantuan achievement. For instance, no charity or market actor can be credited with eradicating a specific disease, but governments have many notches on that belt (Source: Wikipedia). As an example, consider the case of bed nets and malaria. While bed nets are, per capita, the most cost-effective way to reduce malarial infection, the eradication of malaria historically has only been possible through large infrastructural investments in sanitation and water systems made by governments (Source: Council of Foreign Relations). These investments in infrastructure are not cost-effective per capita, but they are historically the only way eradication of the disease has come about.

Reply to objection 4: It is beyond this essay to outline what EA’s actual policy priorities ought to be, but since a dollar spent in a developed nation will not “go as far” as that same dollar spent in a fragile region of a developing country, it is clear that EA must balance developing and promoting foreign and domestic policy in developed and developing nations. Perhaps the majority of EA’s lobbying of developed governments will likely be concerning foreign aid and the regulation of extinction risks, while in developing countries, the focus might be on government responsiveness, sustainable development, and the alleviation of poverty.

Reply to objection 5: Many governments are viciously corrupt, and working with these governments is an ineffective intervention. However, the power of responsive governments is so great that fighting against corruption might represent an important policy priority of EA. As for governments with low levels of corruption, even these could use EA’s brain trust to help implement effective policy.

Appendix 1

These are some examples of models for influencing governments that are not based mainly on participating in traditional partisan politics:

Models for influencing domestic government:

- Funding traditional influencers such as academics and journalists to help move the public, and more importantly political, perception of an issue to a point where politicians will actually act and decide differently. This can be done in a more sinister fashion (see the aforementioned Koch brothers) but is also the legitimate practice of lobbyism (e.g. PACs, 501c4s), think tank work (see e.g. the Institute for Humane Studies, the CATO Institute, various non-profits) and media production (e.g. reason.com, FOX News).

- Founding and/or interacting with business associations and advocacy groups aiming for the mainstream, such as the US Chamber of Commerce.

- Engaging with religious lobbying groups to influence legislation (see e.g. Friends (Quaker) Committee on National Legislation)

Models for influencing foreign governments:

Appendix 2

Government interventions can work as drivers of charitable work too, of the kind you might traditionally associate with EA cause areas. For example, by engaging in fields where scale affects costs a lot, government spending can help scale up production. Let’s look at the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF). Per comments from Rob Mather, the founder and CEO of the AMF, on the cost of malaria bednets: “What brings down prices, and has done so over the last 15 years, is a) competition and b) scale of production.” Now, you might imagine that the AMF is the largest funder of bednets in the world, but in fact, both the Global Fund and the US government are bigger funders (also per comment from Mather). US government funding for malaria control efforts and research activities in just 2021 was $979 million (Source: KFF), roughly double the amount the AMF has raised in total since its inception 18 years ago. It seems very likely that government spending has contributed a lot to the price per net falling from around $5 to $2 over the last ten years since scale is one of the two main factors. This is just a simple example to show how e.g. influencing governments to increase funding towards effective interventions could help not only those interventions directly but also every other actor (e.g. charities) working within that cause area.

I think that this is correct, and it is why such efforts have already begun, many quite a few years ago.