On January 14th 2021, Effective Altruism Philadelphia hosted Jeremy Blackburn and Aviv Ovadya for an event about infodemics as a potential cause area. The following is the transcript of Aviv's talk followed by my interview.

Aviv: I’m Aviv Ovadya, I’ve worked in a number of capacities over the years around these issues. I’m not directly affiliated with the EA community but I’ve been following it’s development from where it spawned 10 years ago, so I’m sort of on the outskirts and trying to use a little bit of that language as I go from Jeremy’s concrete examples -- and I’ve done work in a number of related spaces -- to the sort of high-level framing around the problems, and some of the misconceptions and complexities that relate to this broader problem, whether it’s called information disorder, the information crisis, infopocalypse, misinformation more broadly, and all these other components of it (which we won’t attempt to get into all the details there) but I just want to give some framing. My background; I started as a computer scientist at MIT, did software engineering and product design over the years, but I was also exploring thoughtful technology practices, and then for the last 5 years I’ve been full time focused on ensuring that we have a healthy information ecosystem based off the concern that we’d have the type of disruption we’re seeing right now. This has been something that people thought you were crazy if you talked about it 5 years ago. And it’s been interesting to see the development as there’s different waves of awareness of “oh there actually are very very deep problems with the platforms that exist, the mechanisms for distributing and creating information more broadly, and the other sociotechnical structures around that.” And I guess in terms of concrete places that I’ve been (how I’ve seen things from the ground), I’ve done everything from working with fact-checking organizations like snopes, working on an information triaging engine, to working as a chief technologist at the center for social media responsibility at the University of Michigan School of Information, and a number of other organizations including a journalism fellowship at columbia and so on.

So let’s dive in. What are the components to this problem? You can think broadly of this idea of epistemic competence, not necessarily the only or the best framing, but certainly a valuable one especially for people coming from the EA community. I can define that as the desire and capacity for individuals, organizations, governments etc. to effectively make sense of the world.

That’s sort of what it comes down to at its core. And there’s pieces of that, right, this epistemic competence impacts understanding, decision-making, and cooperation. It’s across every scale, from individuals to the global scale. And there’s a mix of structural/sociological challenges and intentional adversaries that help decrease this.

And we can think about these properties with respect to all sorts of catastrophic risks, which I know is of interest to many in the EA community. E.g. global pandemics: we can see how it impacts all scales from individual to global; “am I going to get a vaccine tomorrow?”, “What is going to be the policy of this country?”, and so on. And the same thing when you’re talking about AI risk, at a very individual level (do you have a google home in your house, and the economics that that creates for the industry), to what should be our global policies and practices.

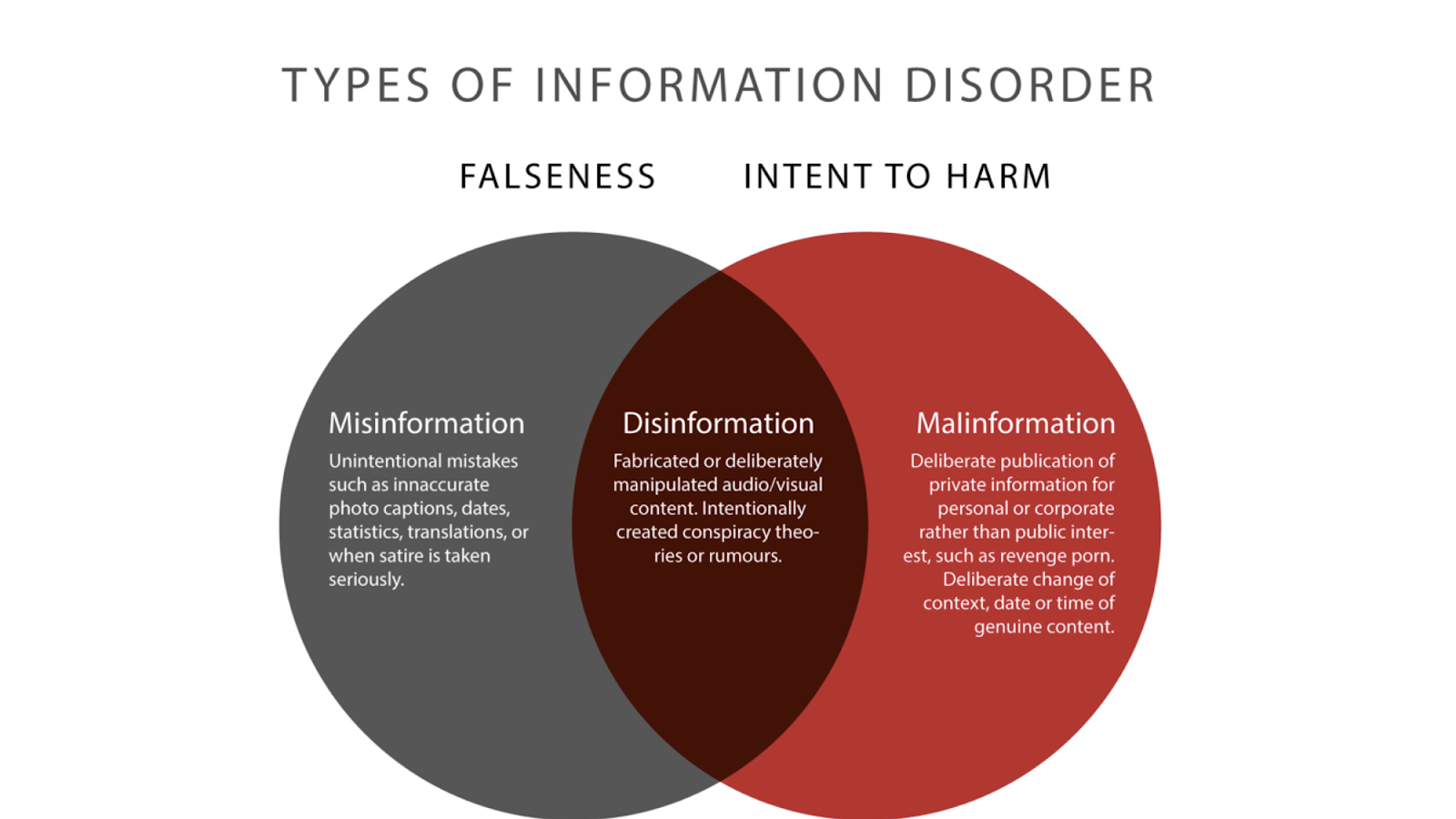

And so you can think about misinformation and disinformation as two parts of a spectrum, or a set of buckets. There’s also this idea of information that’s actually true can be used to cause harm, for example, with cyberbullying. So there’s this broad sense of types of information that can have impact, and can lead to a decrease in epistemic capacity.

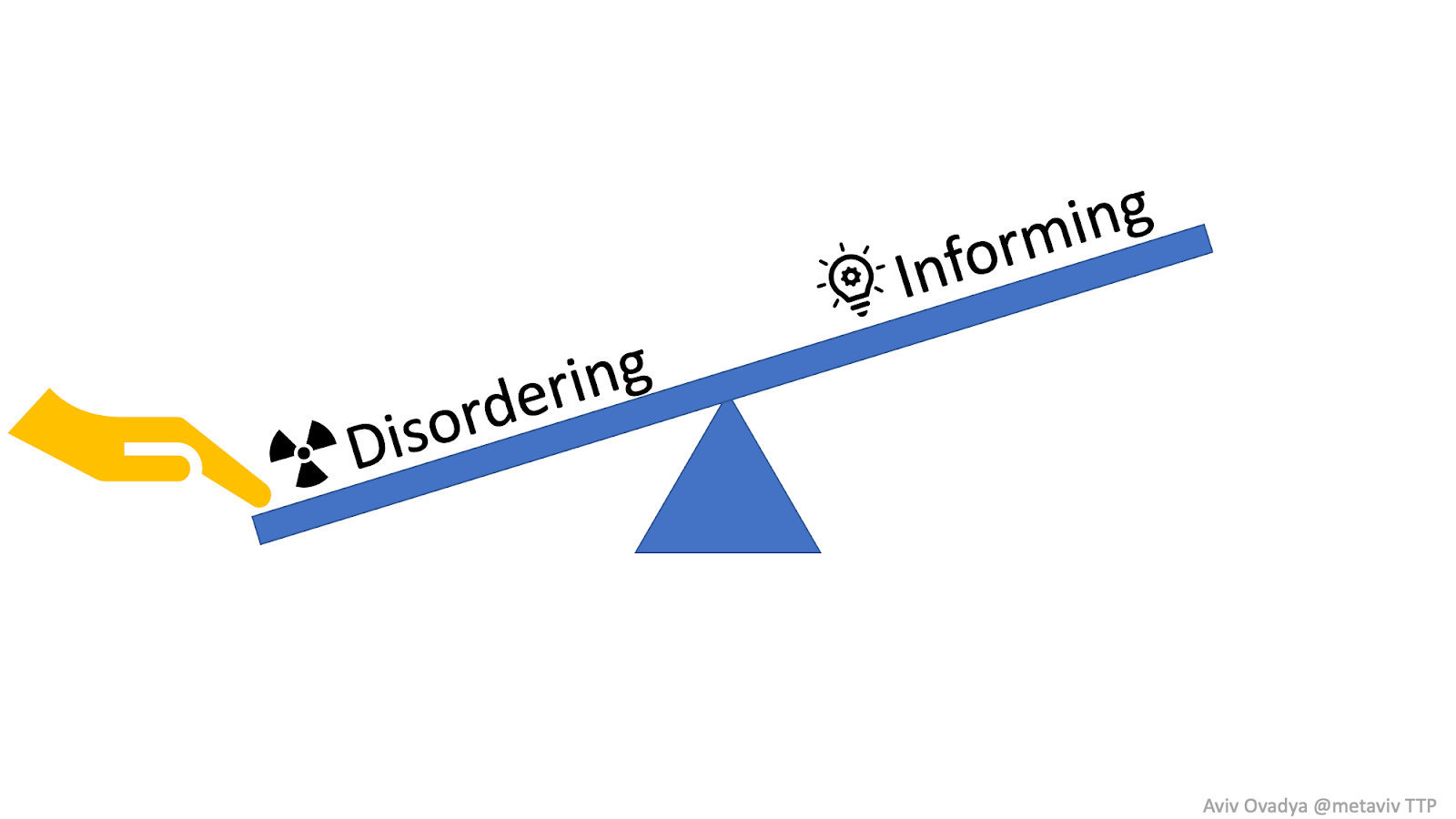

So one frame for thinking about this overall set of problems is you want your underlying environment, your landscape, to be set up so that informing actually leads to more attention, more awareness, more power, more status, and what we have right now is the opposite. Things that actually decrease our epistemic competence lead to more of all of those factors—it’s tilted in the wrong direction. And that’s a problem as we expand out that dynamic to more and more people, we see global internet usage increasing, and you also see increases in particular sorts of violence that can sometimes be correlated with that.

Independent content challenges

So looking at this from a high level, there’s a few different ways of thinking about these challenges. If you’re thinking about misinformation, disinformation, malinformation; you can think of attention allocation as one thing, but most people focus on content quality: is this misinformation or disinformation? And how much of that is there out there? But what really matters even more in many cases is what are we paying attention to? In the space of all the things that exist. And those are very different problems. Decreasing the amount of misinformation doesn’t necessarily decrease the amount of attention directed toward it, and doesn’t even decrease the amount of attention directed away from things that help us understand our world and allow us to make decisions. Then there’s all the questions of how do you govern attention allocation and attention quality?

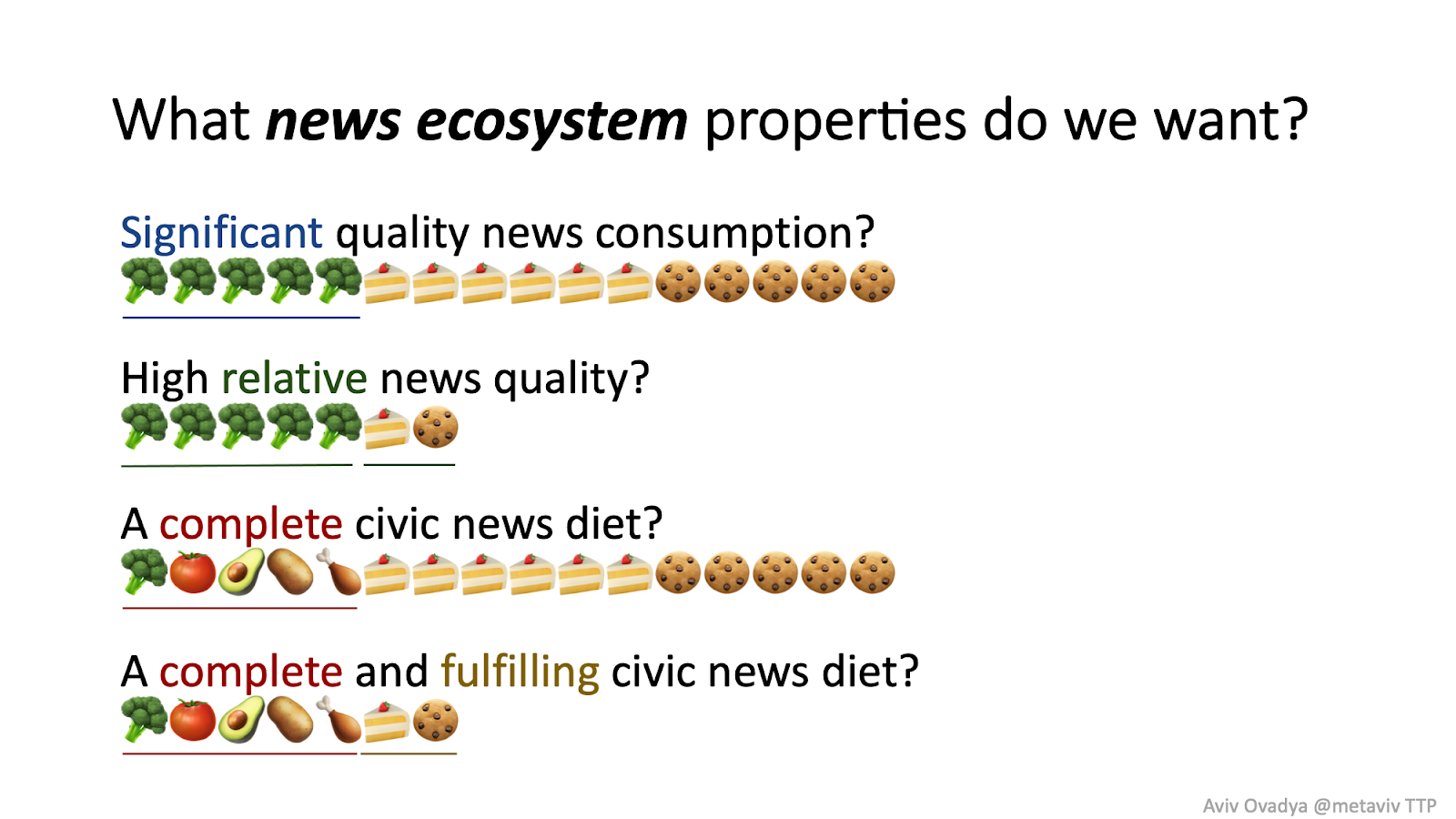

And one way to sort of think about this, think about let’s say the news ecosystem: what do we want? There’s a few different parameters you can imagine: you can imagine, do we want a significant amount of quality news? Well that’s one thing, but that might mean we have a really significant amount of things that actually decrease your overall health. Maybe you want a high relative news quality, but having a lot of high quality news but missing entire sets of issues is also damaging. So you want a complete diet: everything that’s related to things we need to have a functional society and to take care of yourself. But if you still have a lot of crap, you might still be unhealthy. So you need a complete and fulfilling civic news diet. So that’s another way of thinking about the attention allocation and content quality challenges.

Independent process challenges

And there’s an entirely different way of looking at this whole set of issues. There’s incentives around speed and then the actual structures of those communications. If in order to win on the attention marketplace you need to be first, then you don’t have time for fact checking. So there’s a whole set of issues around the economic and status incentives around that, both within news organizations and with platforms and the people who use them.

So if you want to move from a place where disordering wins to a place where informing wins, that requires addressing at least those two frames (and there are a number of others we can go into).

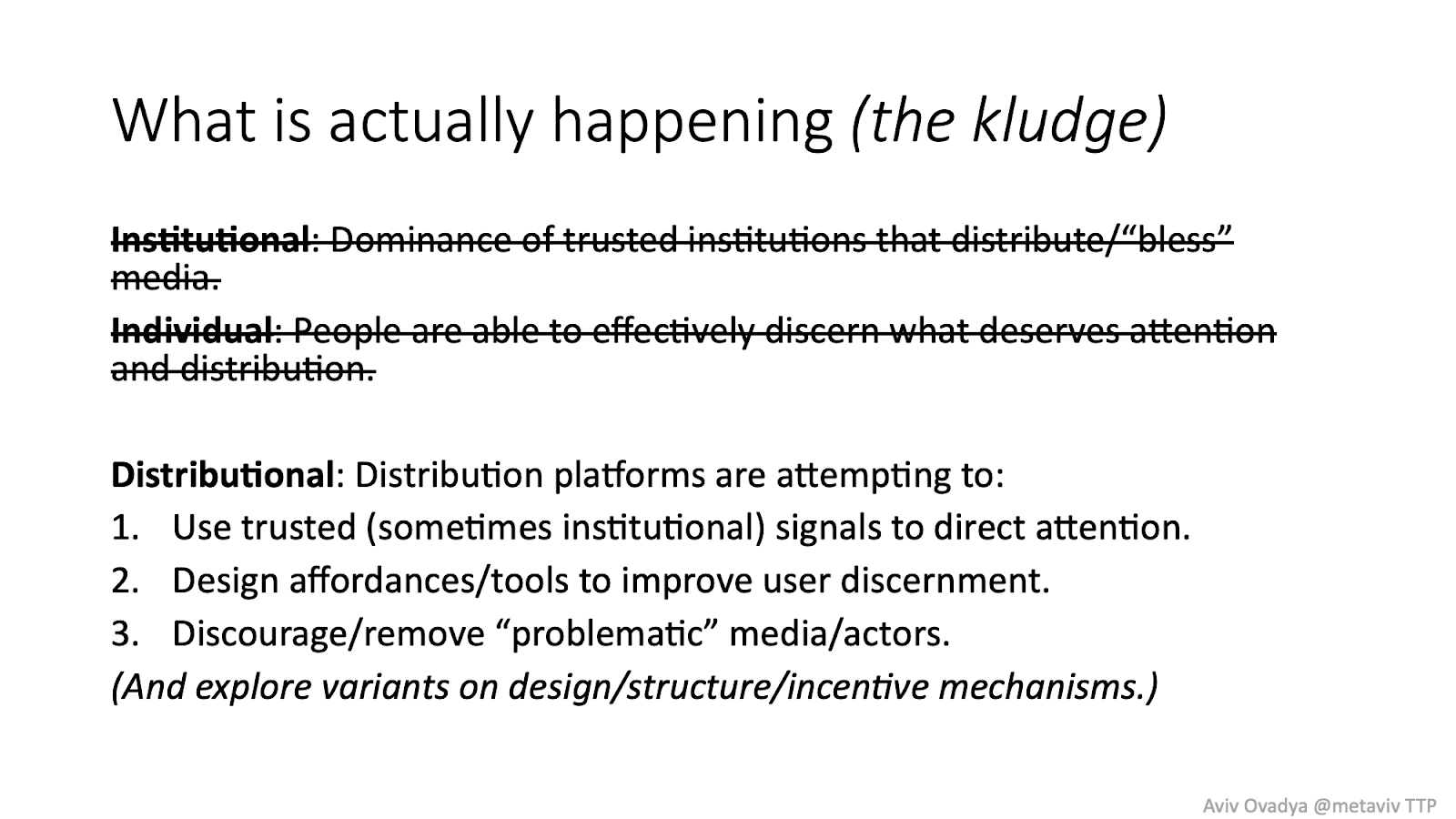

So there are two ways we’ve thought about approaching this problem as a society, there's this institutional way, and there’s the individual approach. The Institutional approach is around dominance of trusted institutions that distribute/”bless” media. These are saying, such and such are the authoritative sources, and this is the sort of default mode that we had before social media in many ways, at least within developed countries that weren’t conflict regions. (In conflict regions you don’t have this, and if you don’t have strong institutions you don’t have this as much). And the other approach is the individual approach, everyone can figure out what needs attention distribution and they can share that amongst themselves. Completely different way of doing things that has its own positive and negative aspects. And you can go into more details about what these approaches have.

The institutional approach has dominance of trusted institutions with sufficiently effective processes for: (1) surfacing and rewarding the best people and knowledge while ignoring deceivers, and (2) drawing attention appropriately to issues of importance (i.e. supply side). And individuals, like this fully democratized ecosystem, requires a populace that’s sufficiently effective at (1) discerning who and what should be trusted, and (2) focusing appropriately on issues of importance (i.e. demand side). Unfortunately there are some real challenges with both of these approaches. And one of the challenges that is the most salient to understand, is that beyond the broad emergent issues we see, there are nation-state adversaries, there are adversaries that are trying to embed the status-quo because they currently have resources. There are corporate adversaries. There are kamikaze adversaries, people who have given up on the world and just want to destroy. And the challenge is these sort of adversaries have more “moral freedom of movement”: they can do whatever they want. They can co-opt institutions, manipulate people, etc.. And there are trillions of dollars at stake.

So the corollary, the really disturbing corollary, if you assume that this entire chain is true, is that individuals will fail at discernment in the face of adversaries with this many resources, this much capacity, and this much moral freedom of movement. “Useful idiots” will multiply, (The term “useful idiots” was used during the cold war to describe people who were co-opted in order to take a cause in their own hands and act as a tool without even realizing it). The challenge here is that this means that only really powerful and wealthy entities have any chance at all of combating these adversaries, of working in this kind of adversarial dynamic. And of course having power and wealth has issues in terms of its incentives, so you need a robust system of checks and balances in order to succeed in the long term.

What is actually happening (the kludge)

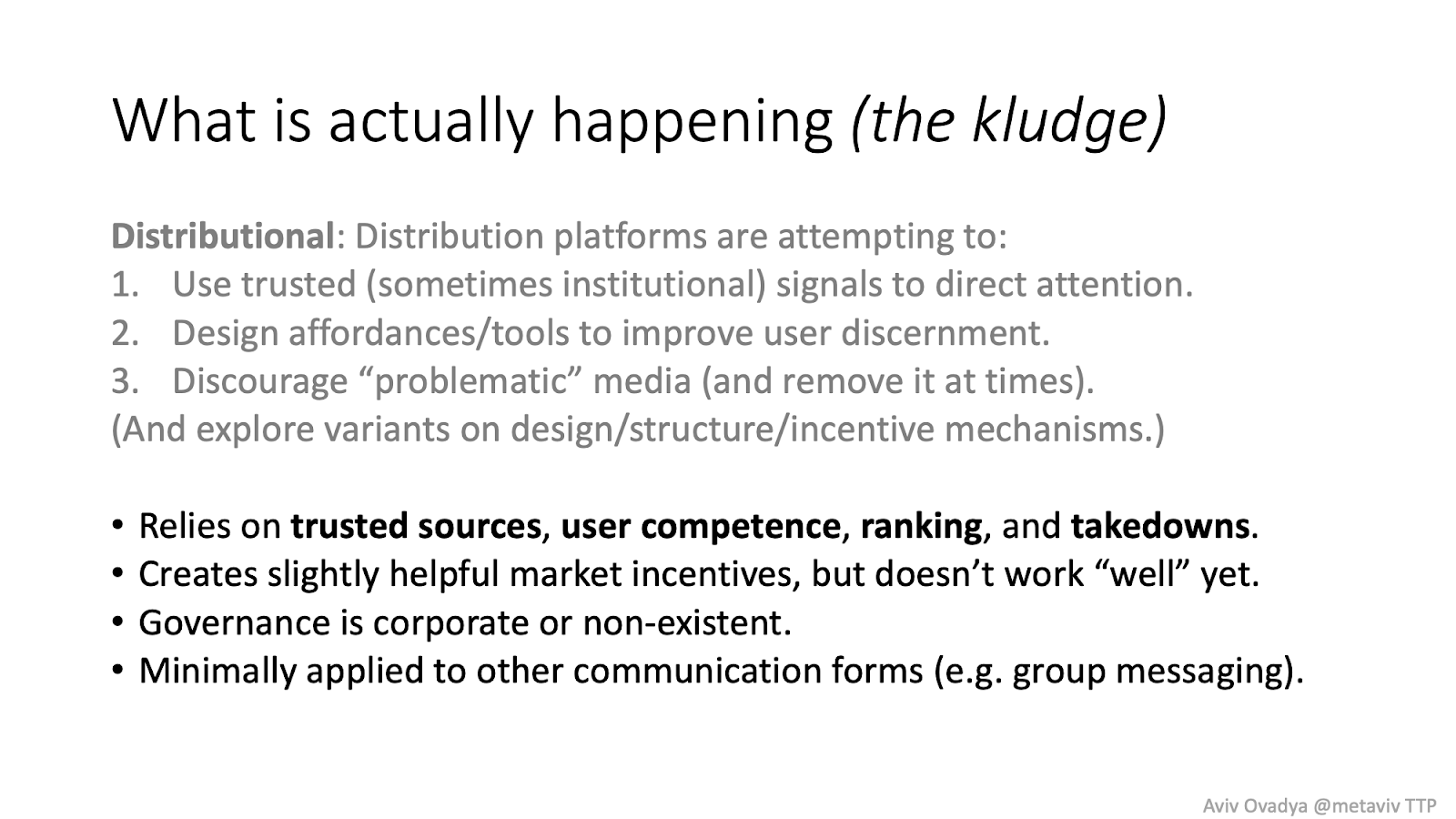

So that’s the sort of world we’re in, and the way that we’ve sort of kludged along so far fairly poorly, but better than nothing, which is what we had 5 years ago when i was first trying to get attention toward these issues at facebook, (and i was far from the first, though I may have the been the first for particular way of thinking about and framing the issue; people especially who were in countries that were more dysfunctional already were raising the alarm much earlier). But what we’ve sort of ended up with is this distributional approach. Distribution platforms are attempting to use trusted (sometimes institutional) signals to direct attention (a little bit), design affordances/tools to improve user discernment (a little bit), and they discourage/remove problematic media/actors (a little bit, (maybe a little bit more as of january 9th)). And there is so much better we could do along these approaches, but this is the frame we’re currently using. What this relies on is trusted sources, user competence, ranking, takedowns. It creates these market incentives that are better but we don’t do it very well at all yet, and the governance is terrible. As Jeremy alluded to, there isn’t enough stuff well thought out that’s happening and if you give this over to ordinary national governments, that could be co-opted. And this approach isn’t at all applied to other communication forms (e.g. group chats, which we see e.g. neonazi organizing on telegram).

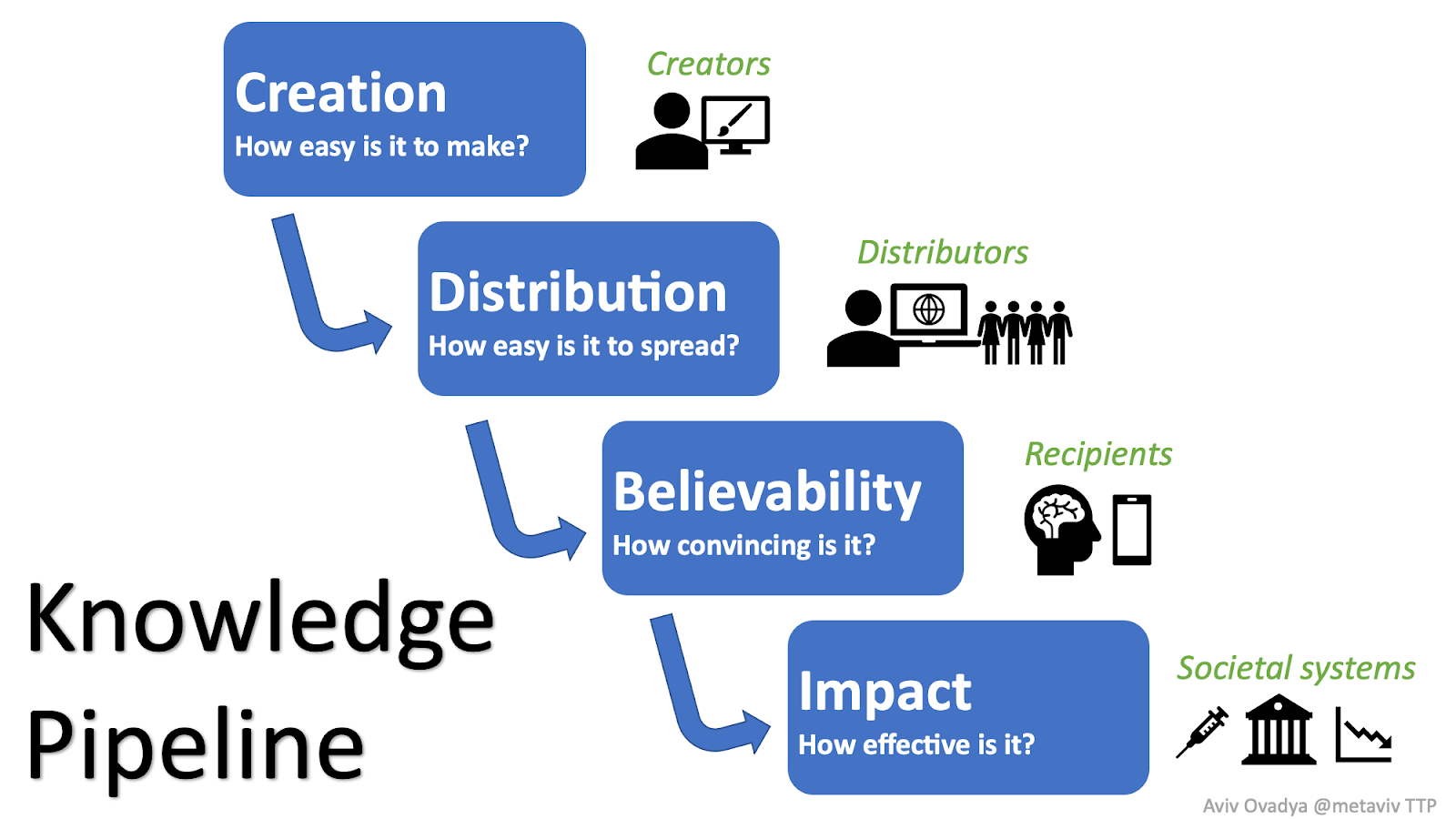

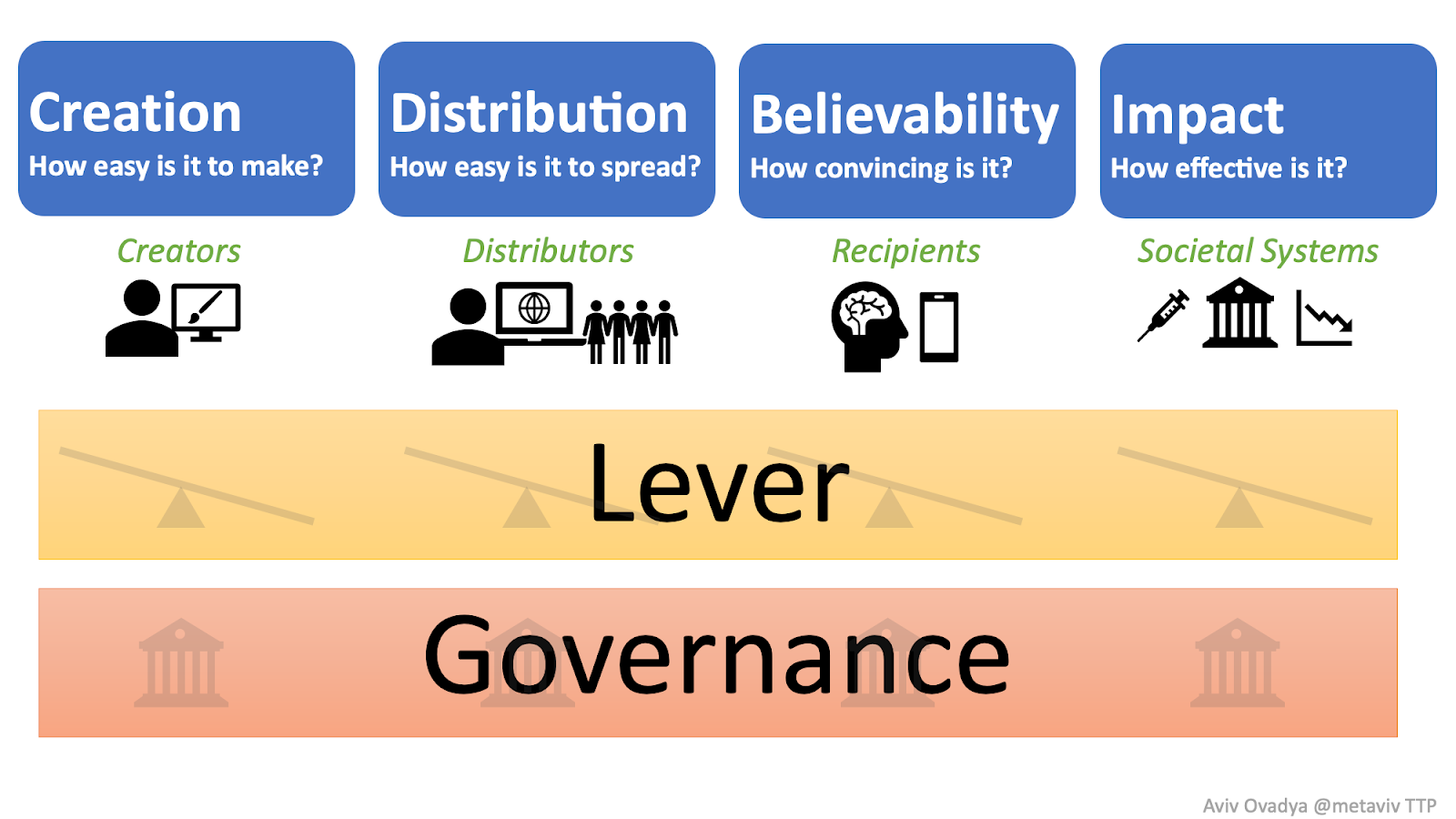

And so if you think about the broader set of frames here, the broader challenge, there’s all these different points of leverage when you’re thinking about how knowledge goes through society and how it effects the epistemic competence of that society. From creation to distribution to believability to impact. And for each of those you can think about levers, at every stage, and you can think about governance for every one of those levers.

And if you want to do this right... you have to build these very very complex safety structures, these sociotechnical systems, in order to ensure that you’re able to maintain the level of epistemic competence that’s needed for a functional society. (read more)

Importance

Quinn: Awesome. Thank you Aviv. So I want to get started with estimating the importance, like you said it effects coordination that effects these other cause areas e.g. pandemics/epidemics, ai risks, I feel like the first order effects of failure to solve this problem is fairly obvious

Aviv: At this point yes, having this conversation which I did have with EAs 5 years ago, it was considered sort of not a thing. At this point I think people have realized, whether you care about the climate crisis or global pandemics, you need to have epistemic competence and we clearly don’t have it.

Quinn: Right. Can you think of more second-order or third-order effects of failure to solve this problem? As in cascading failures

Aviv: yeah, I mean basically if you’re not able-- I don’t think we’ll make it through the next 20 years at this level of society and technological capacity if we don’t address these issues. There’s a number of crises that are coming down the pipeline (societal technical debt), climate crisis among them, which will cause mass migrations, which will cause political upheavals, and if we’re not able to handle those basic things not to mention who knows what could happen as a result of specific new developments in technology which could completely change the structures of power whether it be something that’s like physically drone based or more AI and abstract, we’re not going to be able to handle those issues. A lot of these issues require global coordination. And that will be deeply destabilizing, in a way that I think nobody who has not lived in a conflict region will be able to understand just what that feels like.

Tractability

Quinn: Could you speak more about what the points of leverage are? And how identifying these poitns of leverage might impact career choices?

Aviv: Yeah. There are a lot of points of leverage, because this is a very multifaceted problem and it touches many many disciplines. In the last few days I’ve talked to people in international relations, in crisis counseling, in journalism, there’s a very broad space of tools that are relevant to this set of issues. But if I was going to bucket the leverage points, I would go back to my slide about creation, distribution, believability, impact. There are many many things in creation, many things in distribution, in believability, in impact. And each of those has their own governance challenges that need to be addressed. So I’m just going to go into some examples.

- Product design for platforms. Huge point of leverage. There are a few specific aspects there that are absolutely crucial. One of them is the specific affordances of the product; the things that are made easy, the way it makes people feel. The specific design around that. Are you feeling more isolated? If you’re about to send a message that is likely to make really someone unhappy, maybe you should get a suggestion about how that could be rephrased in a way that actually helps you achieve your goals better in that communication. There are different levels of heavy-handedness. What are the specific interactions that make sense in terms of “like”ing, like what does a “like” do and how do you see it? Then you could go into recommendation engines. There’s so many really important decisions around how a recommendation engine works, and selection engines are core to everything you do. In any environment with more than 5 things you need something to help you choose among them, and any interaction of the internet has more than 5 things. And so that determines your reward function, status, money, power, attention. And there's many things you can do in that specific domain that can completely change the economics and incentives of the ecosystem. And that’s just in product.

- We haven’t gotten into policy, we haven’t gotten into the actual decision-making structures, the sociotechnical decision-making structures of society itself and the way that effects your epistemic capacity. E.g. how a congress is structured: what are the ways in which the interactions and the rules of that body actually impact our epistemic capacity. What are the ways in which international organizations are structured? So there’s a whole suite of things that aren’t just about social media that relate to this.

- And then you have norms and practices within different fields. So Jeremy talked about “oh wow, the things I’m doing are being misused in this way, that’s really terrible, what can I do about this?” and that redirected his entire research agenda. That type of “oh wow, let me reevaluate and understand my impact” is not a thing that happens much in the AI community. So I spent a bunch of time on synthetic media norms and practices, how are the people who are thinking about deepfake technology thinking about their impact? And working on the norms and practices there, and that’s now a project area for the Partnership on AI, which is a really good move in that direction, there’s a few other initiatives around that.

- And I can keep going, in governance, there’s a number of things we can do to help ensure that neither national governments nor the platform corporatocracy actually determines what policies are, but there are ways of actually creating democratic structures for some of these decision-making questions, where the platforms don’t want to make that decision, because for PR reasons it’s better to give a mandate to the people. But elections don’t work, in many contexts. So there are other democratic structures that you can implement at scale, and that are actually aligned with their[who’s?????] incentives. and that’s a whole nother set of issues that I could talk for 5 hours about.

- And there's the question of storytelling. What are the positive visions that we need to create in society, ways of giving meaning to people, in ways that people can imagine a world where they don’t just have exit they also have voice. Where it’s not that they can just leave the thing and go to something else, where there is often not something else, but they can actually have agency in impacting that, and it completely changes the way people interact with the community and interact with all their relationships.

So there are all these points of leverage, and it’s far from complete, these are just a few of the things that come ot mind, but it’s a question of why are they under-resourced, or not deployed well enough to have impact. And part of this is that many of these things are really interdisciplinary, you need many hats at the same time, many lenses. The first three months I was doing this work, I just read in 20 different fields. That was my introduction to this space. And that was after 10 years of doing more general work on information ecosystems. And a really big part of this, and why a lot of things fail, is there isn’t enough humility and curiosity in the people who end up working in this space. And so people charge on in one very specific direction, not able to understand the little bits and tweaks that come from these other fields and are able to integrate that knowledge. So that’s a very long answer to this question, but hopefully gives a sense of what exactly is happening.

Neglectedness

Quinn: Who’s currently working on this and who should be working on this?

Aviv: There are a lot of people working on this in different capacities now. I will say in the frame in which I started working on this has gone from on the order of a handful of people, in early 2016, well that’s not true it really depends on how you count. There’s always been many many people working on this in some abstract sense, since this ties into so many fields. The question is, number of people who are working on this in a goal oriented way, with any amount of influence, and who are able to put on the necessary hats, and look through the needed lenses. And that number I think is way higher than it was a few years ago, but it is still far from sufficient. And I wish I could say “you know, here is a list of people”, I mean Jeremy and I could probably talk all day about people in different specific subfields of this. But whether or not they actually have sufficient leverage and resources? That’s it’s own separate question, that’s a big problem.

Quinn: One more thing before I open it up to the audience. Where can people donate if they want to put cash into this problem?

Aviv: So my perspective on this is, especially coming to the EA community, you mentioned the EA funds [in my 5-minute opener], I think that what we need here in some cases are new institutions, there are people who are sort of working on this but they can’t act on it in many cases, because the institutional structure they're in doesn’t give them that freedom of movement. Or there isn’t an institution that’s really focused around a specific leverage point, which I see all the time in conversations with people in the space. And they’re sort of trying to fit themselves into a thing that doesn’t quite fit, and they can’t do the thing they need to do. So I think having an EA Fund around this is probably gonna be much higher impact, especially when you’re not devoting $5000, $3000 for little things, for example I can take a donation of $50,000, I can’t take a donation of less right now, because I need to be able to launch a new project area. So smaller amounts are not going to be helpful for my organization at this point. And I think that’s going to be true because you’re trying to start a new institutional form that addresses a particular set of issues, and that isn’t something you’re gonna do with small donations, unless you already have that institution then you can use it as a maintenance fund.

And if I could be a little more specific about what I mean by institutions, there are like 10 organizations with very specific missions and mandates that don’t exist and need to exist. That’s the kind of thing I’m trying to describe. You need the startup capital for that, and you need to create those teams that actually have that capacity, and also have the humility to redirect as they go.

I may or may not post part 3, which would be highlights from audience questions with crosstalk between Jeremy and Aviv.

The Thoughtful Technology Project is hiring a head of ops