I'm requesting comments and feedback regarding Giving Coupons, a novel mechanism that combines gift-giving, advocacy, and philanthropy, ultimately making charitable giving fun, social and viral.

Introduction

Catalysing charitable giving through viral, coupon-driven donation campaigns.

Built on the idea of "giving the gift of giving", Giving Coupons leverages existing donations to raise awareness of charities, provide social proof of charitable giving, and spark new donations, ultimately multiplying the impact of each donation, and creating a viral giving effect.

Mechanism

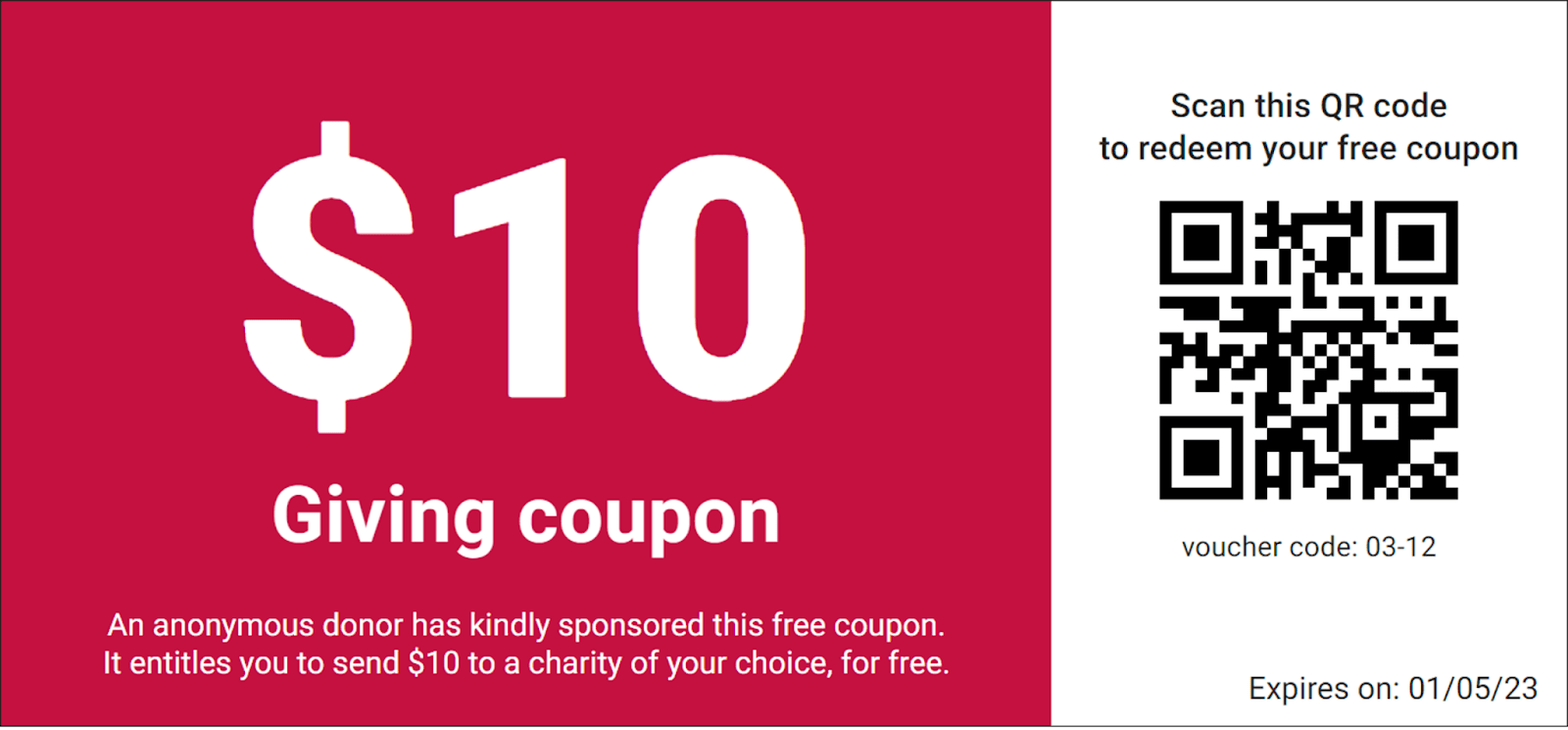

As an example, suppose Alice decides to give $100 to three of her favourite charities to celebrate her birthday. Using the Giving Coupons website, Alice creates ten $10 coupons and sends one to each of her friends. These coupons essentially allow her friends to decide how to split the $100 between the three charities.

When her friend Bob receives a coupon, he redeems it on the Giving Coupons website where he sees and reads about the three charities that Alice has selected. Bob then picks one of them to send the $10 to.

After her friends have finished indicating their choices, Alice then distributes her $100 to the three charities accordingly. Furthermore, Alice's friends are also prompted to optionally match the donation with their own money (perhaps as a birthday gift to Alice), creating a money-multiplier effect on the original $100. Such a system allows Alice to raise awareness of her favourite charities while multiplying the impact of her donations.

Giving Coupons aims to be a fun and social way to give the gift of giving. Unlike a traditional donation matching campaign, Giving Coupons allows coupon recipients like Bob to participate in charitable giving without having to necessarily donate their own money. By requiring users to choose between charities, we encourage them to learn more about each charity, prompting questions about cause prioritisation and charity effectiveness. Giving Coupons creates opportunities for people to engage with each other, reflect on their values, and inspire each other to be more generous.

Giving Coupons is a flexible mechanism that can be applied in a variety of contexts:

- Individuals creating campaigns to promote their favourite causes

- Corporations engaging their employees or the public by distributing coupons to them

- Philanthropic foundations seeking to multiply their donations through the community

- Schools distributing coupons to students as an educational activity

- Governments engaging their citizens with participatory budgeting

- Grantmakers promoting their projects

- Event organisers using coupons as gifts or prizes

- Influencers seeking to share their wealth and generosity

- Leaders who want to publicly set an example

These coupons can be physical or digital. They can serve as currency, gifts, or incentives. They can be used as tools for marketing and advocacy. They can make giving a part of everyday interactions.

Strategy

The success of Giving Coupons relies on the money multiplier effect and the viral effect.

When coupon recipients match the coupon value or otherwise make their own contribution, this creates the money multiplier effect on the original sum of money committed. A multiplier of 10% would mean that every $100 donated through Giving Coupons generates an additional $10 given to charity. This is a clear, measurable metric that would be attractive to donors seeking to maximise the impact of their giving.

When an individual gives coupons to 10 friends, and some of these friends give coupons to 10 more, a chain of giving is created. This viral effect is key to the true success of this project, allowing Giving Coupons to become a self-sustaining, self-promoting movement.

Status and Next Steps

I personally ran a few successful trials achieving a multiplier effect of up to 20%. I'm now seeking comments, feedback, collaborators and pathways to scale up this project.

What do you think of this idea? Would you use something like this? What are some reasons it might not work? How can/should I scale this up? Please do let me know what you think in the comments, I would appreciate all feedback.

I gave comments on this directly to Wayne. I'd encourage others to comment (decently high VOI perhaps), and I'll share my comments later so as not to bias.

I'd be interested in seeing your comments David!

This is potentially very exciting idea! Some thoughts:

Hi Rasool, thanks for your questions!