This report is the fourth in a sequence presenting the results of Wave 2 of the Pulse project by Rethink Priorities (RP). Pulse is a large-scale survey of US adults designed to track and improve understanding of public attitudes toward effective giving and different impactful cause areas over time. Wave 2 of Pulse was fielded between February and April of 2025 with approximately 5600 respondents.[1] Results from our first wave of Pulse, fielded between July and September of 2024, can be found here, with the forum sequence version here.

This part of the Wave 2 sequence focuses on a collaboration with FarmKind; an organization that promotes effective giving in the farmed animal welfare space.[2] This collaboration involved developing and testing the effects of messages related to donations, and the effects of including information about not needing to change one’s diet to help animals. Although the timing of this post coincides with a recent FarmKind campaign (initially ‘Forget Veganuary’ and subsequently ‘Can’t give up meat’),[3] the message testing discussed here was not conducted in preparation for that campaign, and the precise messages tested were less provocative. Nevertheless, the findings may help inform discussion around the campaign, as well as broader debates about messaging related to donations and diet change.

Findings at a glance

Survey features:

- Wave 2 of Rethink Priorities’ Pulse project surveyed approximately 5,600 US adults between February–April 2025, following up on Wave 1 (July–September 2024).

- Results were analyzed to be representative of the US adult population with respect to age, sex, income, racial identification, educational attainment, state and census region, and political party identification.

- For these experiments, analyses were conducted to generate estimates for the US adult population, for US adults not already engaged in diet change or in donating (‘Not active’), and for those who were not active and at least somewhat sympathetic to farmed animal welfare as a cause area (‘Not active, sympathetic’)

- We used a light touch, message-based experimental manipulation in which a Control group answered an unrelated question, a Donation group read a message about how donations are an effective means of improving farmed animal welfare, and a Diet distancing group read a message about how donations were effective and that it was not necessary to change one’s diet in order to benefit animals.

Immediate responses to the messages

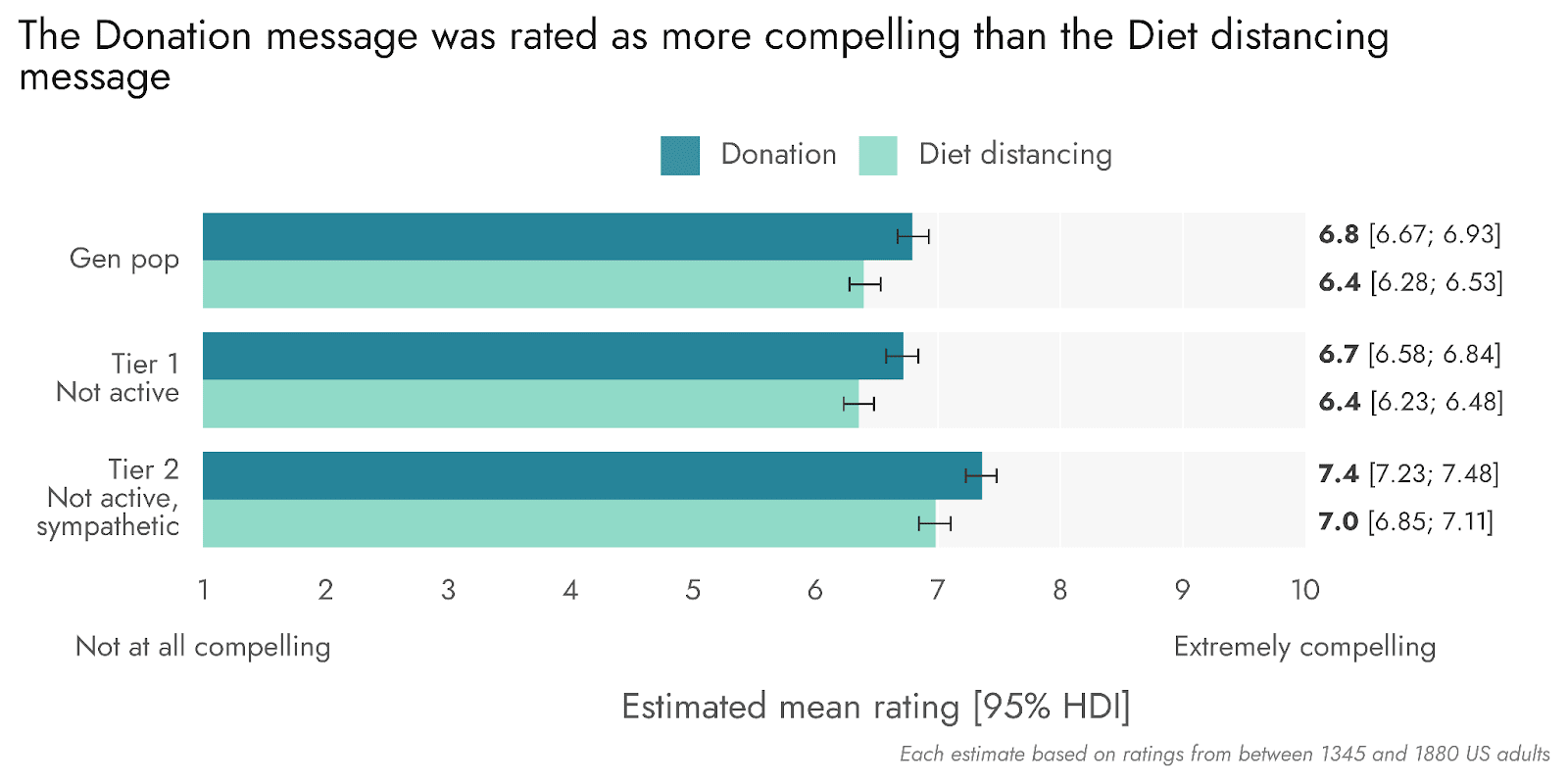

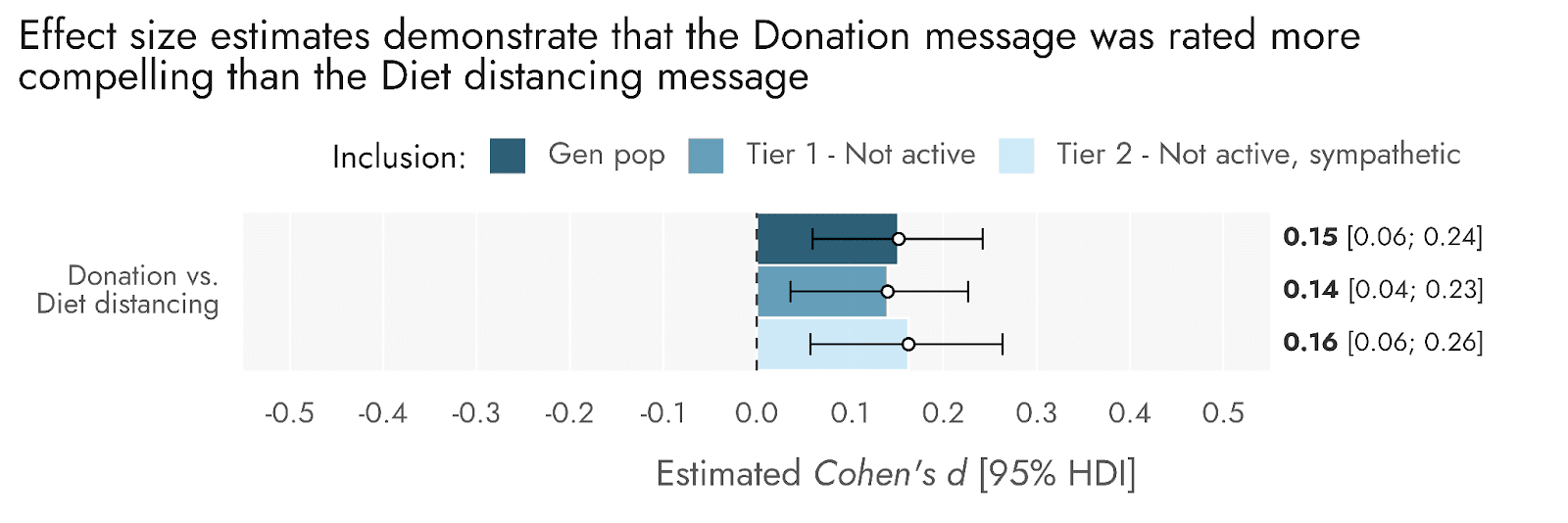

- The Diet distancing message was rated slightly less compelling than the simple Donation message. This difference was small but statistically reliable, at approximately 0.3 to 0.4 units on a 1-10 scale, corresponding to an effect size of around 0.15 standard deviation (SD) units.

Perceptions of donating vs. diet change

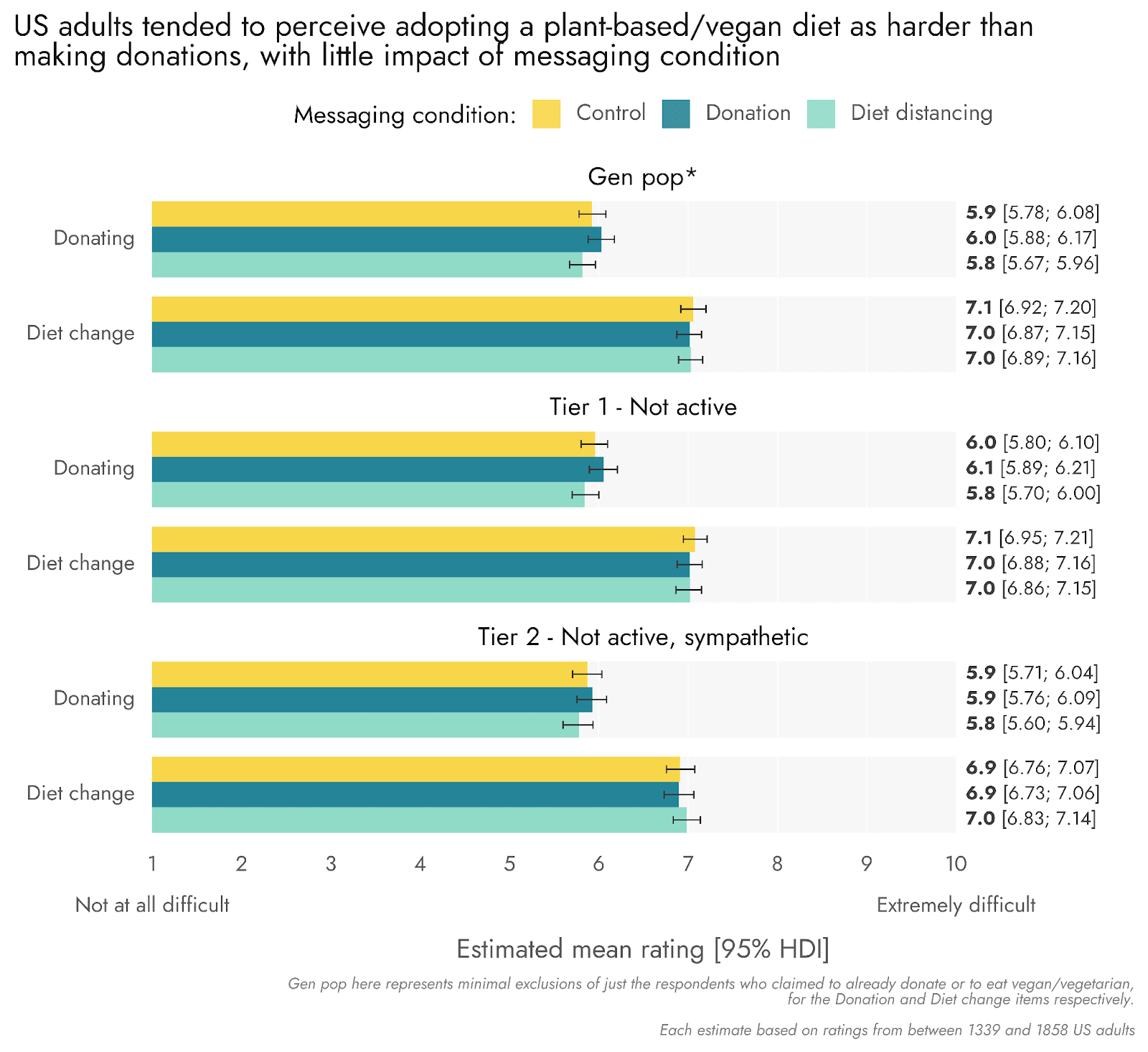

- Diet change was consistently rated as more difficult than making donations. This difference was moderate at approximately one point on the 1-10 scale, and 0.3 to 0.4 SD units.

- Messages did not reliably impact the perceived difficulty of either donations or diet change.

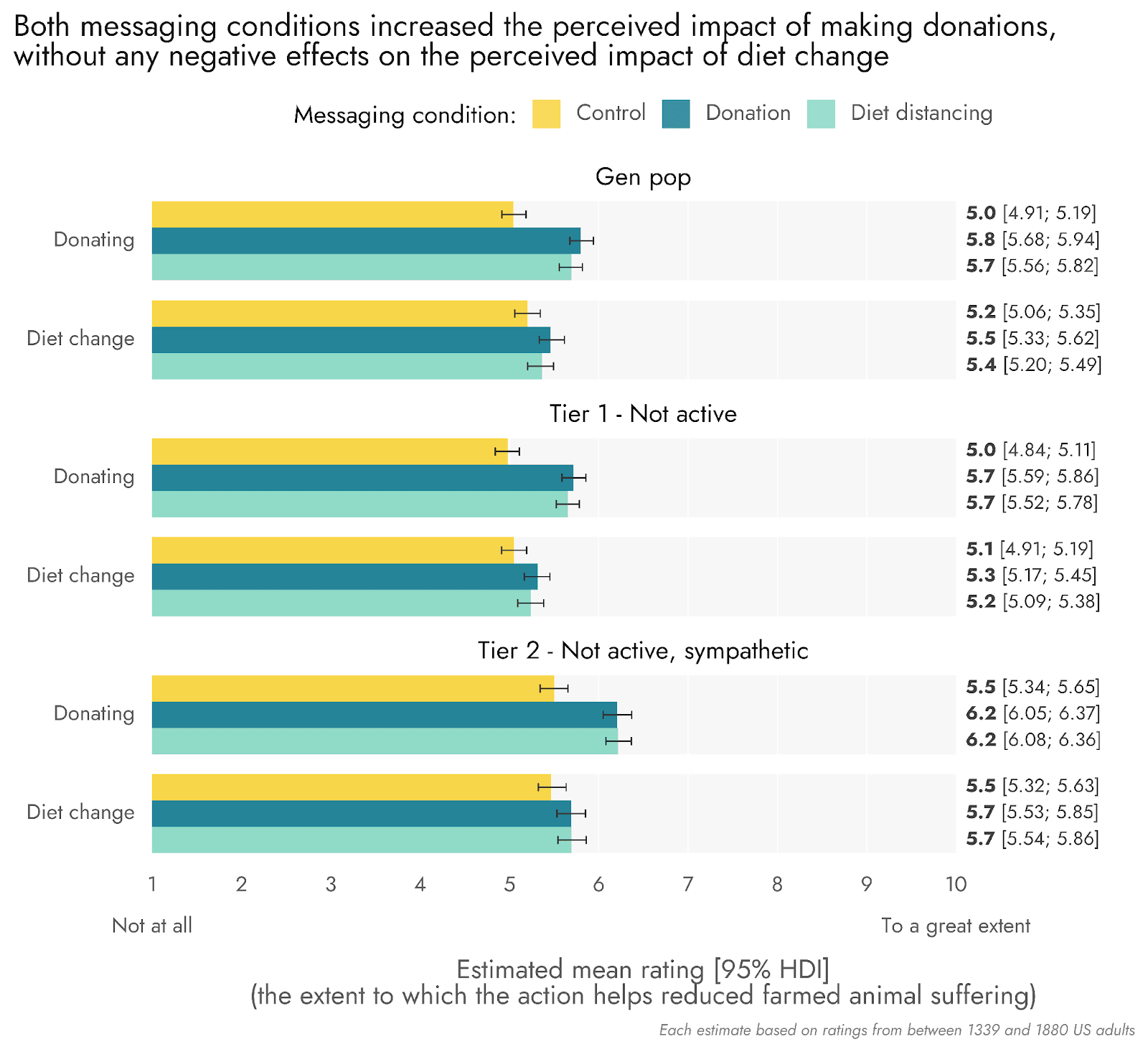

- Control respondents rated diet change and donating as equally impactful, and both messages increased the perceived impactfulness of donating. This shift was quite small at about 0.7 points on the 1-10 scale, or 0.23 to 0.27 SD units, but resulted in these groups rating donations as more impactful than diet change.

- They had this effect without reducing the perceived impact of diet change.

- Respondents reported being more inclined towards donating than diet change, whether or not they received a message (approximately 0.7 points from 1-10, or 0.23 to 0.30 SD units), and Donation messages very slightly increased reported interest in diet change (around 0.3 points from 1-10, or 0.09 to 0.13 SD units), with the Diet distancing message directionally the same but smaller in magnitude (around 0.1 or 0.2 scale points, or 0.06 to 0.07 SD units).

- Directions of such effects were similar across different inclusion groups, so we do not discuss them independently. Compared to the other inclusion groups, Non-active, sympathetic respondents had similar difficulty ratings, but tended to find both messages slightly more compelling, viewed both diet change and donations as more impactful, and reported slightly more interest in engaging in both behaviors.

Assessing a donation-related behavior

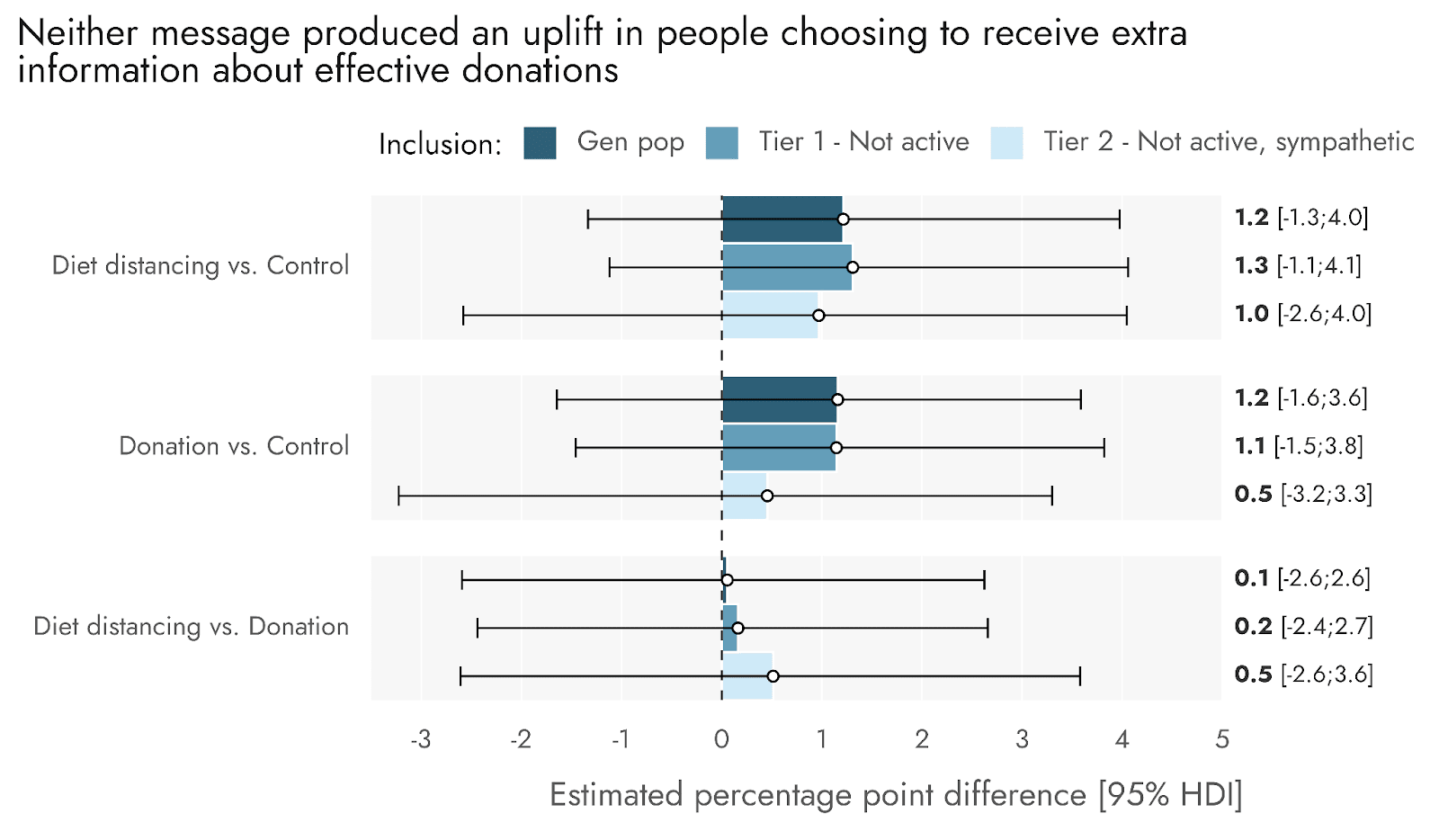

- Though directionally consistent with an increase, neither message reliably increased respondents' likelihood of choosing to receive more information about effective donations.

- We do not weigh this outcome too heavily, as the option to receive information was purposely not persuasive or linked with either message (to avoid people feeling pressure to engage in more uncompensated activity), and it occurred after a delay. We also expect that there are constraints of the survey context, such as fatigue or perceiving the offer as spam, and more general issues such as limited statistical power to detect small but meaningful percentage shifts.

Updates for messaging and advocacy

- Unsurprisingly, but consistent with the theory of change of organizations such as FarmKind, people do perceive donating as less difficult than diet change. This suggests that donating could be a lower-threshold activity with which to engage people in efforts to improve animal welfare.

- The findings suggest that messaging with a ‘diet distancing’ emphasis was slightly less compelling than a pure donation message.

- The net effect on real-world impact is unclear: ‘diet distancing’ could plausibly achieve greater reach through novelty and consequent shareability, but we did not assess this possibility.

- FarmKind noted that this finding had updated them towards keeping their web homepage focused on a simple donation message: it might be more compelling, and people have already arrived at the intended destination by the point of visiting the site.

- The type of diet distancing message tested in this study did not negatively impact perceptions of diet change, suggesting that diet distancing is a viable and not intrinsically ‘zero-sum’ messaging option. However, the same may not apply to messaging that is, or can be taken to be, more disparaging of diet change.

Introduction

While much of the Pulse survey is dedicated to a consistent battery of questions we intend to continue asking over time, we reserve some space for unique questions each time, sometimes in collaboration with or at the request of other philanthropic or charitable organizations. In this second wave of Pulse, we collaborated with FarmKind:

“FarmKind requested this research to better understand the optimal "first ask" for the farmed animal cause area and how to navigate the "meat paradox" (the cognitive dissonance meat-eaters feel when prompted to think about factory farming).” Aidan Alexander, Co-Founder at FarmKind.

After discussing FarmKind’s theory of change, and a range of more theoretical vs. more applied research possibilities, we decided to investigate how US adults responded to messages promoting effective giving towards farmed animal welfare that did, or did not, explicitly distance the opportunity from diet change (i.e., whether donations were presented simply as an opportunity to help animals, or if it was also explicitly stated that one does not need to change one’s diet in order to help animals). We further assessed whether such promotions of donations negatively affected perceptions of diet change as a means of benefiting animals, and how difficult people found donations or diet change.

Experimental design

Outcome variables

Key outcome variables related to perceptions of two behaviors people might engage in to reduce farmed animal suffering.

Donating:

“Donating $25 per month to the best charities that focus on farmed animal welfare”

And diet change:

“Adopting a plant-based diet (i.e., stopping eating meat and animal products entirely)”

For both these actions, respondents were required to rate their perceived impact:

“To what extent, if at all, do you think each of the following individual actions can help to reduce farmed animal suffering/improve farmed animal welfare?”, from 1 (Not at all) to 10 (To a great extent).

Difficulty:

“Given your current life circumstances, how difficult would you find it to take each of these actions?”, from 1 (Not at all difficult) to 10 (To a great extent extremely difficult).

And interest in engaging in the behavior:

“How interested, if at all, are you in taking the following actions within the next 3 months?”, from 1 (Not at all interested) to 10 (Extremely interested).

We stressed individual actions because we wanted to focus on the effects of specific actions people can take and over which they have control (for example, a person cannot choose for everyone to change their diets, even if this would be something that would be very impactful or desirable). However, it is a limitation that we did not have space to ask about a host of other possible individual actions, including those that might be conducive to more collective action, such as advocacy for diet change, or indeed for effective giving.

As explained in the Experimental conditions section below, respondents in the two active experimental conditions additionally rated how compelling they found a donation-related message that we showed them, and which functioned as a key experimental manipulation:

“How compelling, if at all, do you find this perspective?”, from 1 (Not at all compelling) to 10 (Extremely compelling).

At the end of the experiment, respondents were also given the opportunity to receive more information about donating to the best charities working to fix factory farming,[4] and we analyzed whether they wished to receive such information or not. This option was presented in a way that was not promotional and was deliberately quite far from a real appeal to donate, or to receive information about donating, due to concerns over compromising the perceived independence of the research or pressuring participants to engage in further actions for which they would not be compensated.

Experimental conditions

Respondents were randomly split into three conditions: Control (n = 1857), Donation (n = 1871), and Diet distancing (n = 1880), which received different messages about how donations can benefit farmed animals.[5] Respondents in the Control condition did not see any donation-related message and directly answered the Impact, Difficulty, and Interest questions. Those in the Donation condition were presented with the following message:

"Donating even a small amount to the best animal welfare charities is one of the most powerful ways to end the cruelty of factory farming. These organizations are scoring major victories - freeing millions of hens from cages, securing stronger legal protections for animals, and developing alternatives to factory farming. Donating helps them create meaningful change, protecting animals from suffering today and building a kinder food system for tomorrow."

They then rated how compelling they found the message, followed by answering the impact, difficulty, and interest questions. Respondents in the Diet distancing condition instead saw the following message:

"You don't have to change what you eat to make a big difference for factory farmed animals. Whatever your diet, donating even a small amount to some of the best animal welfare charities can be just as impactful as going fully plant-based.

These organizations are scoring major victories - freeing millions of hens from cages, securing stronger legal protections for animals, and developing alternatives to factory farming. Donating helps them create meaningful change, protecting animals from suffering today and building a kinder food system for tomorrow."

They then similarly provided a ‘compellingness’ rating, followed by impact, difficulty, and interest ratings. The primary difference between the two messages is that the Diet distancing message explicitly highlights that one does not have to change one’s diet in order to help farmed animals, and that donating to the most effective farmed animal welfare charities can be just as effective as changing one’s diet.

Similar arguments to the Diet distancing message are articulated on some sections of FarmKind’s website. This messaging fits with FarmKind’s view that many people may be motivated to help animals, but see diet change as the principle means by which to help. Because diet change is notoriously difficult, they often fail to act on their desires to help. Acknowledging this challenge while providing an alternative way of helping can bring people to act on their desires to improve the plight of farmed animals.

However, it is an open question whether such a Diet distancing message is more compelling than simply highlighting the opportunity to donate, or perhaps even less effective (e.g., perhaps people might take issue with the idea that you can benefit animals simply with money, while still eating them). An alternative possible downside of such messaging might be that it decreases the perceived impact of diet change, or people’s desire to change their diets. While short-term message testing cannot address the long-term effects of such messaging, it can provide some signal for the possible direction of such effects. Immediate perceptions and responses to such messaging are also of direct interest, as they could be the difference between a person taking action after reading content on a website or messaging campaign, or not.

Inclusion subgroups

Results and analyses for the outcomes were split across some different tiers of inclusion. On the most inclusive level, we have results representative of the US adult population (‘General population’, or ‘Gen pop’ in graphs). For items that refer to Difficulty and Interest in engaging in the specified Diet change or Donation behavior, this General population level excludes those who reported already being vegetarian or vegan, or those who claimed to already be donating to such animal welfare-related charities, respectively (because they had the option to answer ‘not applicable, I already do this’).

Tier 1 excludes those who have engaged in either behavior, and so is representative of the US population who have not already mobilized to act in these particular ways to benefit farmed animals - we refer to this tier as ‘Not active’.

Tier 2 additionally excludes those who are unlikely to be sympathetic to farmed animal welfare as a cause area in general. Hence, we refer to those included as ‘Not active, sympathetic’. This inclusion/exclusion is done by selectively including those who reported being at least slightly supportive in principle of donations to farmed animal welfare earlier in the survey, or who selected six or more on a scale from 1 to 10 for the importance of farmed animal welfare as a cause area (i.e., above what seems to be the implicit neutral point on the response scale).

Findings

How the Donation vs. Diet distancing messages were perceived

As shown in Figure 1, the Donation message was rated as more compelling than the Diet distancing message. The effect size for this difference is quite small at approximately 0.15 standard deviation units (Figure 2). As would be expected, Tier 2 respondents - who are sympathetic towards farmed animals as a cause area - also tended to find the messages more compelling than did the population at large.

Figure 1: The Donation message was rated as more compelling than the Diet distancing message

Figure 2: Effect size estimates demonstrate that the Donation message was rated more compelling than the Diet distancing message

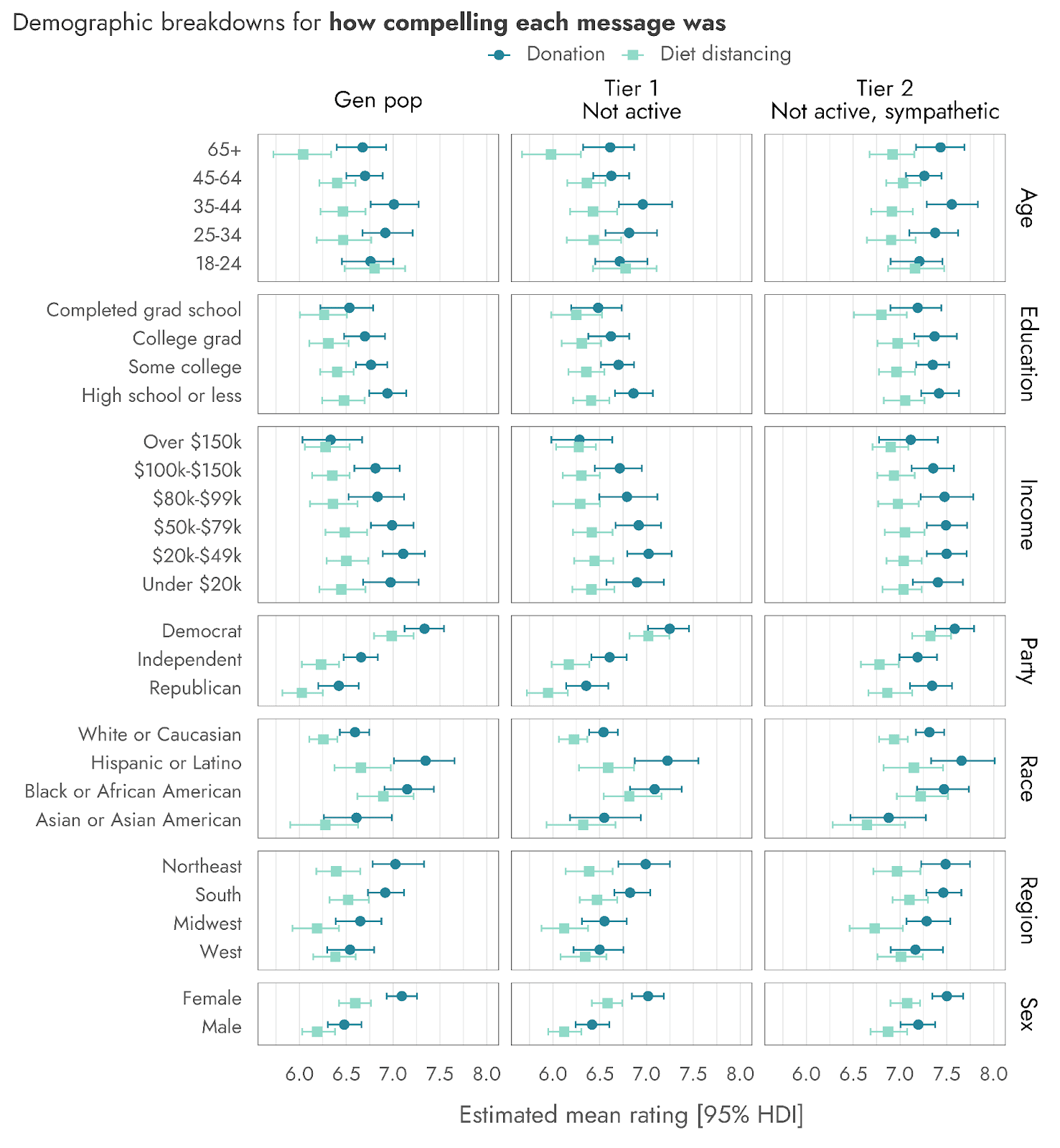

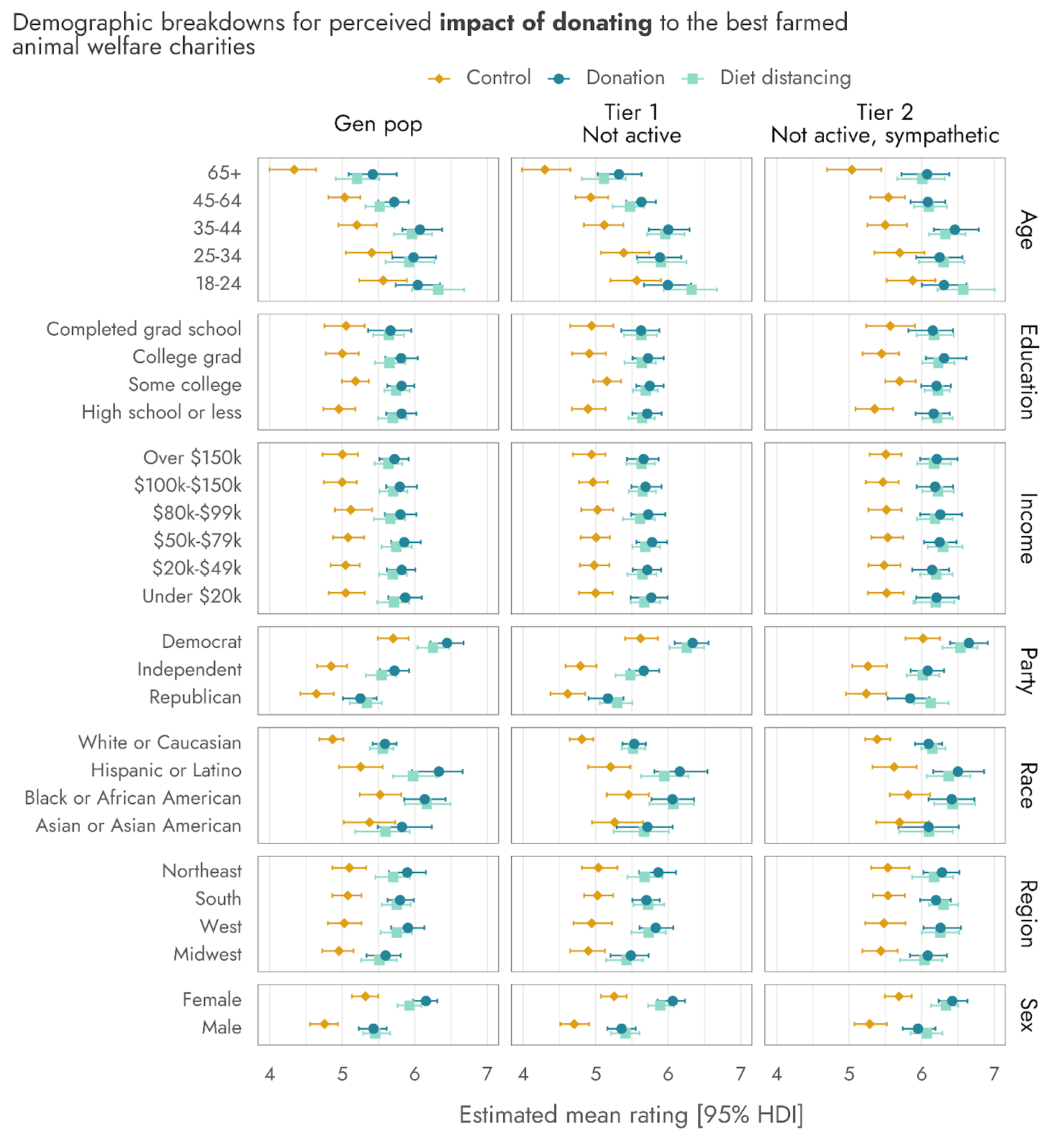

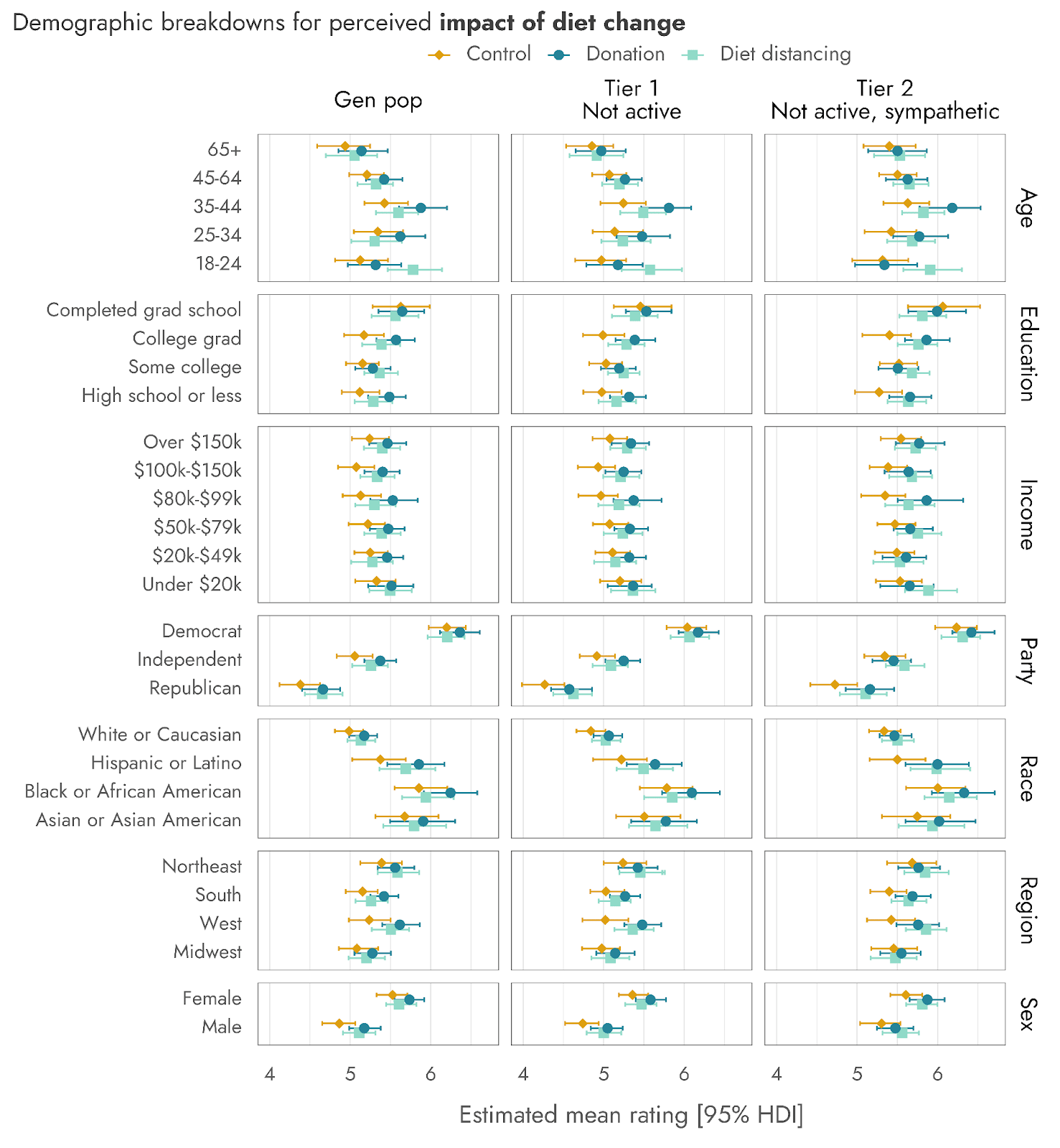

Looking at particular subgroups of the population can also help to understand where people might be particularly receptive to such messaging. Demographic breakdowns for both messages can be found in Figure 3. Numerous potential patterns or trends can be observed, but here we note that female respondents tended to find both messages more compelling than male respondents. Respondents who identified as Democrats gave considerably higher ratings than did Republicans, but these differences narrow when selecting for people who are more receptive to animal welfare as a cause area. One surprising observation is that there were sizable racial differences in responses, with respondents who identified as Hispanic or Latino and Black or African American finding the messages more compelling than did White or Caucasian and Asian or Asian American respondents (though the difference with White or Caucasian respondents is reduced among sympathetic respondents).

Figure 3: Demographic breakdowns of how compelling each message was

How messages affected the perceived impact of donating and diet change

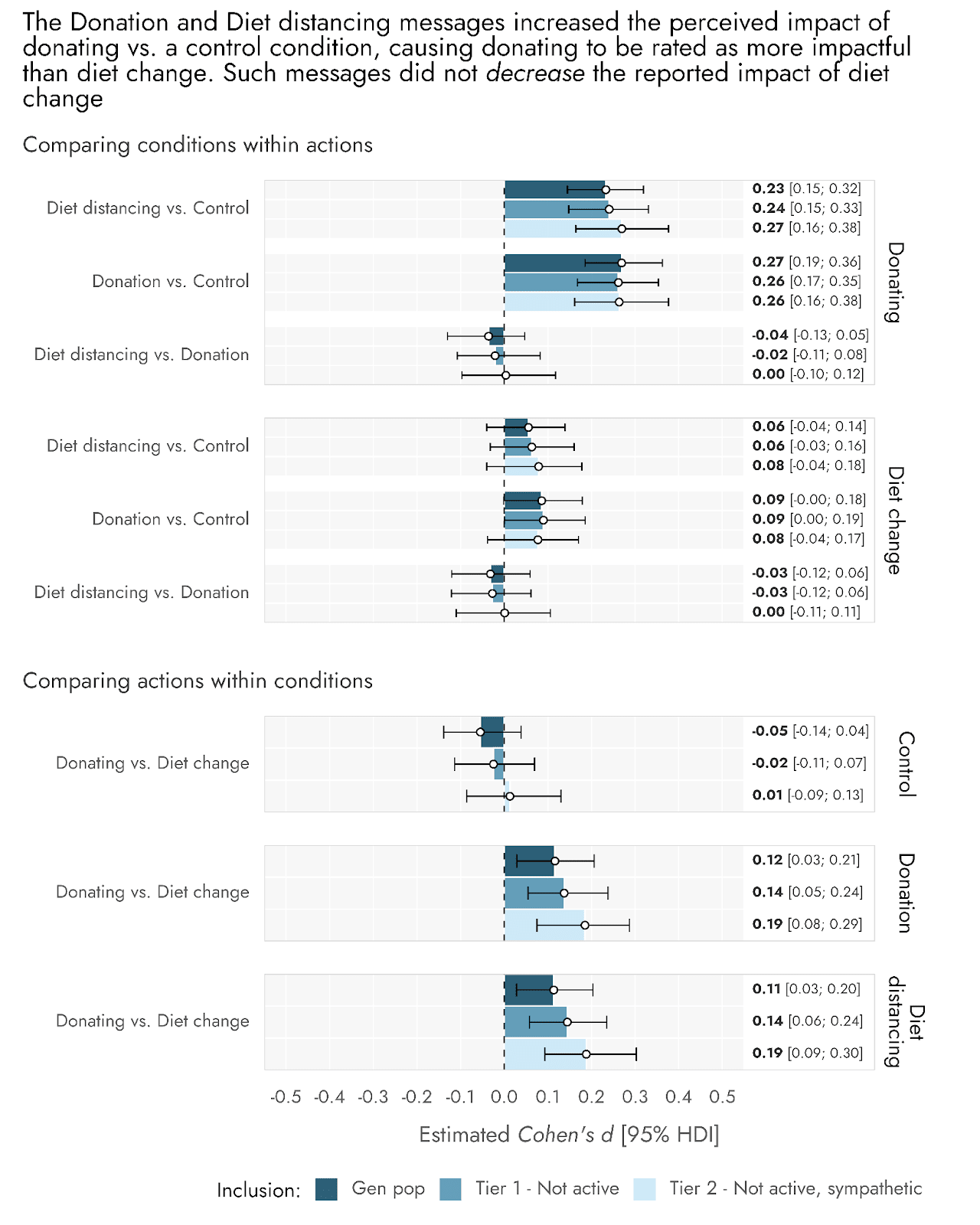

Both the Donation and the Diet distancing message increased the perceived impact of making donations, with a small to moderate effect size (Figures 4 and 5). As a consequence of these shifts, respondents who had been exposed to the messages rated donating as more impactful than diet change, whereas these actions were rated as equally impactful by those in the Control (no message) condition. Crucially, however, neither message reduced the perceived impact of diet change, and directionally, they even slightly increased the perceived impact of diet change.

Figure 4: Both messaging conditions increased the perceived impact of making donations, without any negative effects on the perceived impact of diet change

Figure 5: The Donation and Diet distancing messages increased the perceived impact of donating vs. a control condition, causing donating to be rated as more impactful than diet change. Such messages did not decrease the reported impact of diet change

As with ratings of how compelling each message was, demographic breakdowns of impact ratings show that female respondents (vs. male) and Democrats (vs. Republicans) perceived both donating and diet change as more impactful (Figures 6 and 7). The perceived impact of donating was remarkably stable across income and education levels, whereas for diet change, there was a slight tendency for those with higher formal education to rate diet change as more impactful than the less formally educated. Both actions showed age trends, with older respondents finding donating less impactful, whereas for diet change there was a peak in impact ratings among those aged 35-44. Interestingly, among those predisposed to farmed animal welfare as a cause area, the age trend for donations is somewhat flattened.

Figure 6: Demographic breakdowns for perceived impact of donating to the best farmed animal welfare charities

Figure 7: Demographic breakdowns for perceived impact of diet change

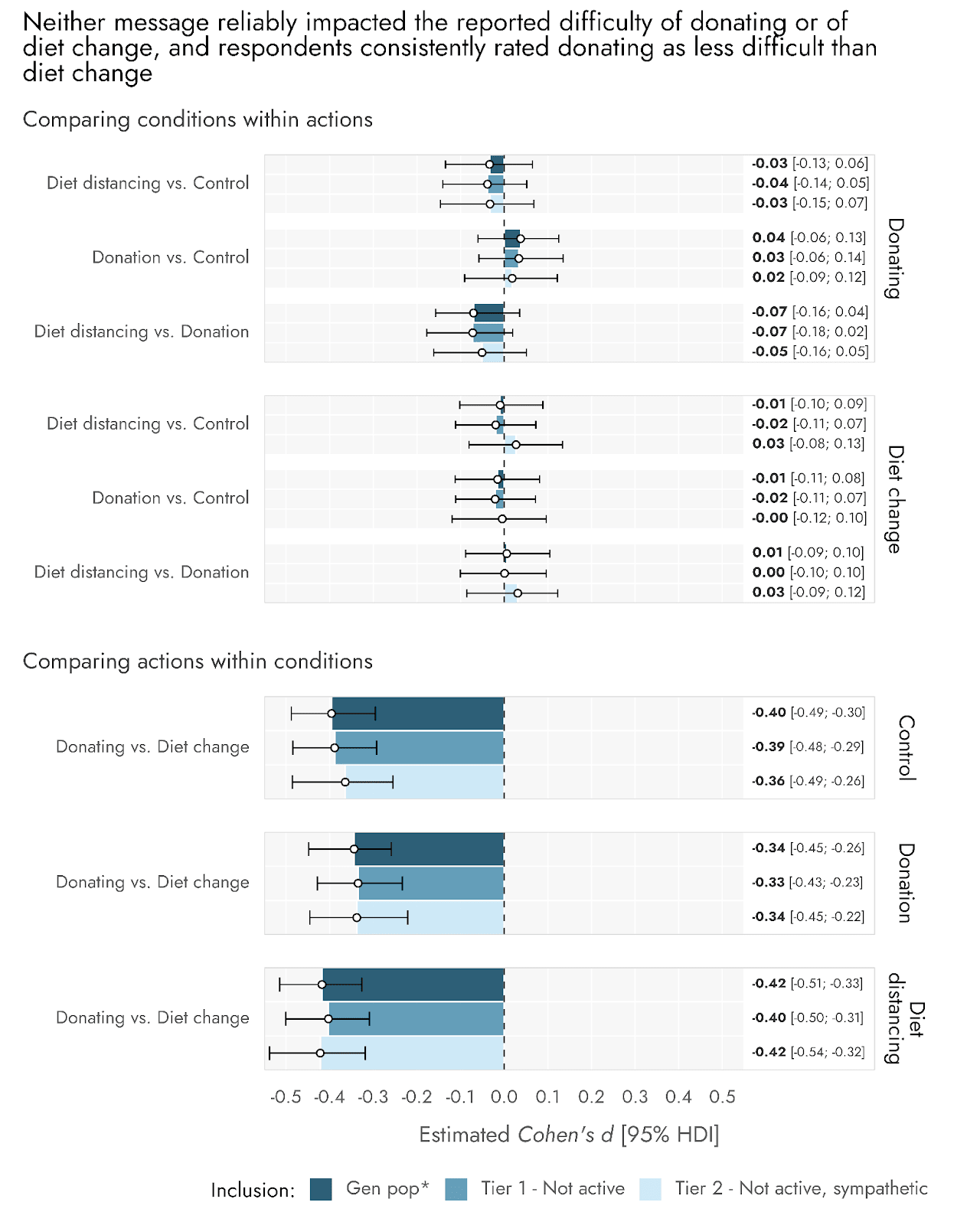

Diet change is harder than donating, and the messages do not affect perceptions of either one

Consistent with FarmKind’s view, we found that people rated diet change as harder than making donations, with a medium effect size (Figures 8 and 9), though neither action was viewed as especially easy on average. Neither the Donation nor the Diet change message had any reliable impact on perceptions of difficulty, and difficulty ratings are also quite consistent across inclusion tiers.

Figure 8: US adults tended to perceive adopting a plant-based/vegan diet as harder than making donations, with little impact of messaging condition

Figure 9: Neither message reliably impacted the reported difficulty of donating or of diet change, and respondents consistently rated donating as less difficult than diet change.

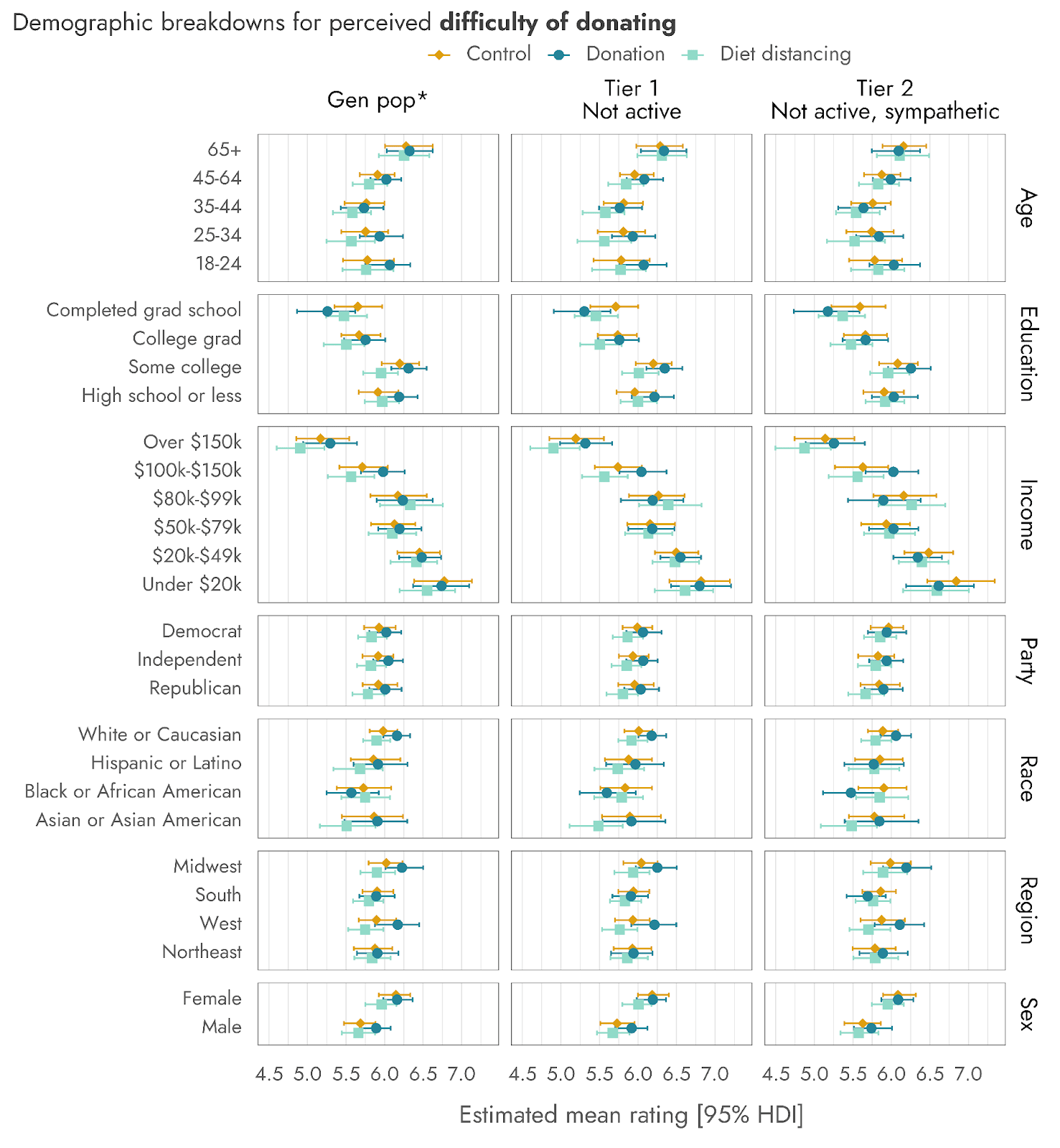

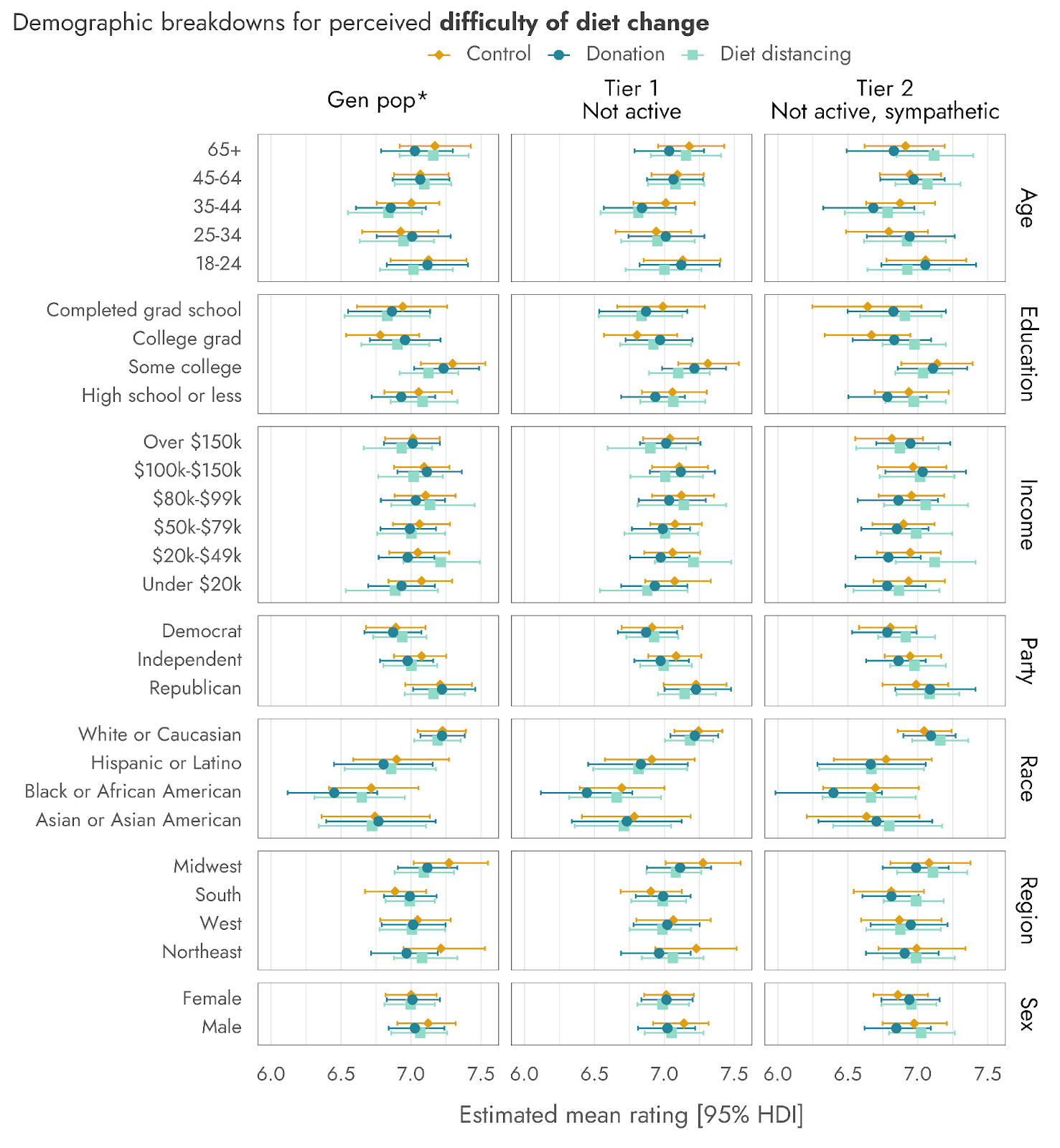

Looking at demographic breakdowns may help reveal those who would be most able to make donations or engage in diet change (Figures 10 and 11). Understandably, there is a clear trend for people with higher household incomes to anticipate less difficulty in making donations than those with lower incomes. In contrast, there is little variation in the reported difficulty of diet change across income levels. Still, even among the lowest income groups, the difficulty of making donations did not exceed the difficulty of diet change. For both donating and diet change, the 35-44 age group in particular stands out as often reporting the lowest difficulty ratings.

Figure 10: Demographic breakdowns for perceived difficulty of donating

Figure 11: Demographic breakdowns for perceived difficulty of diet change

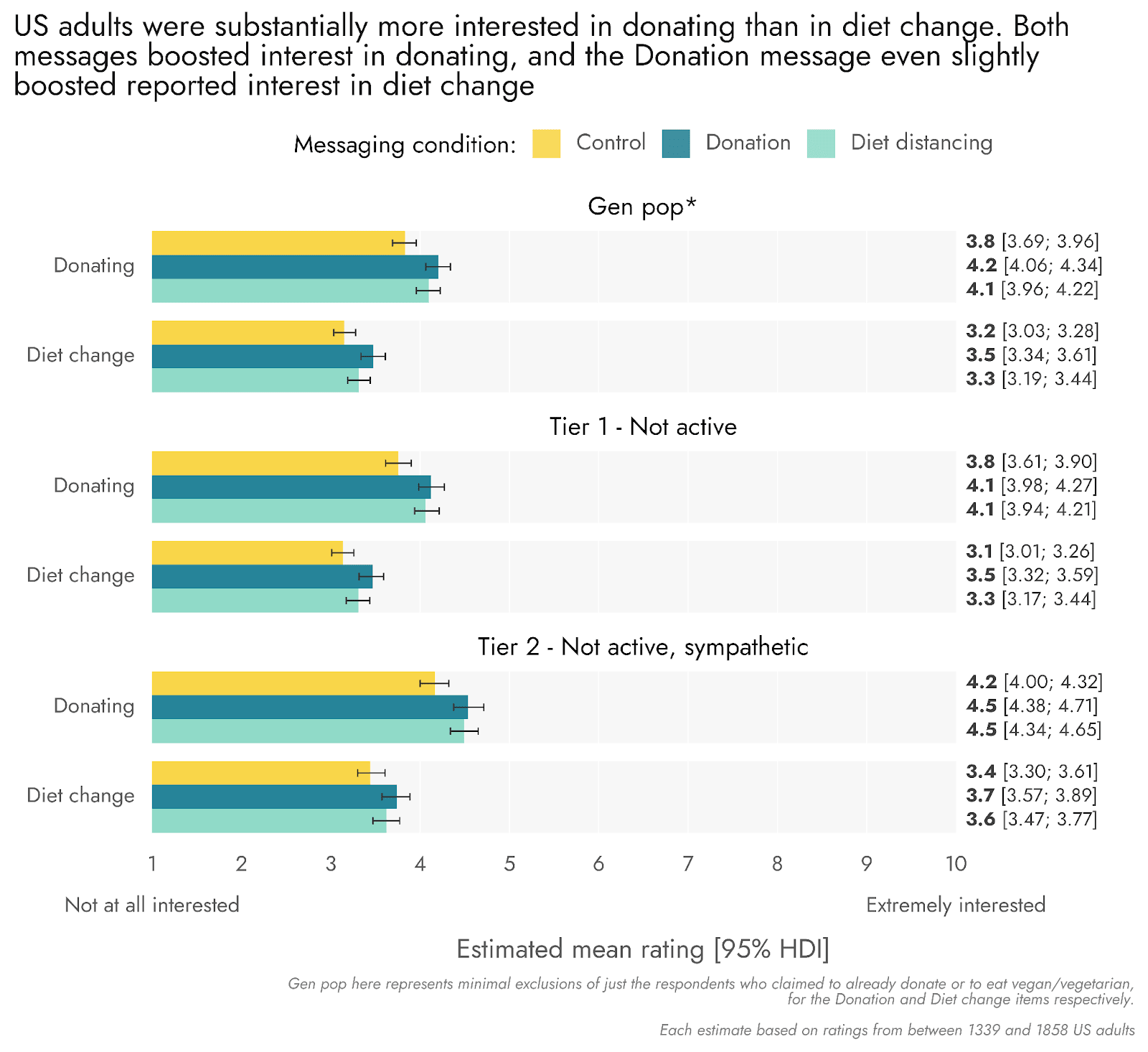

How messages affected interest in donating or diet change

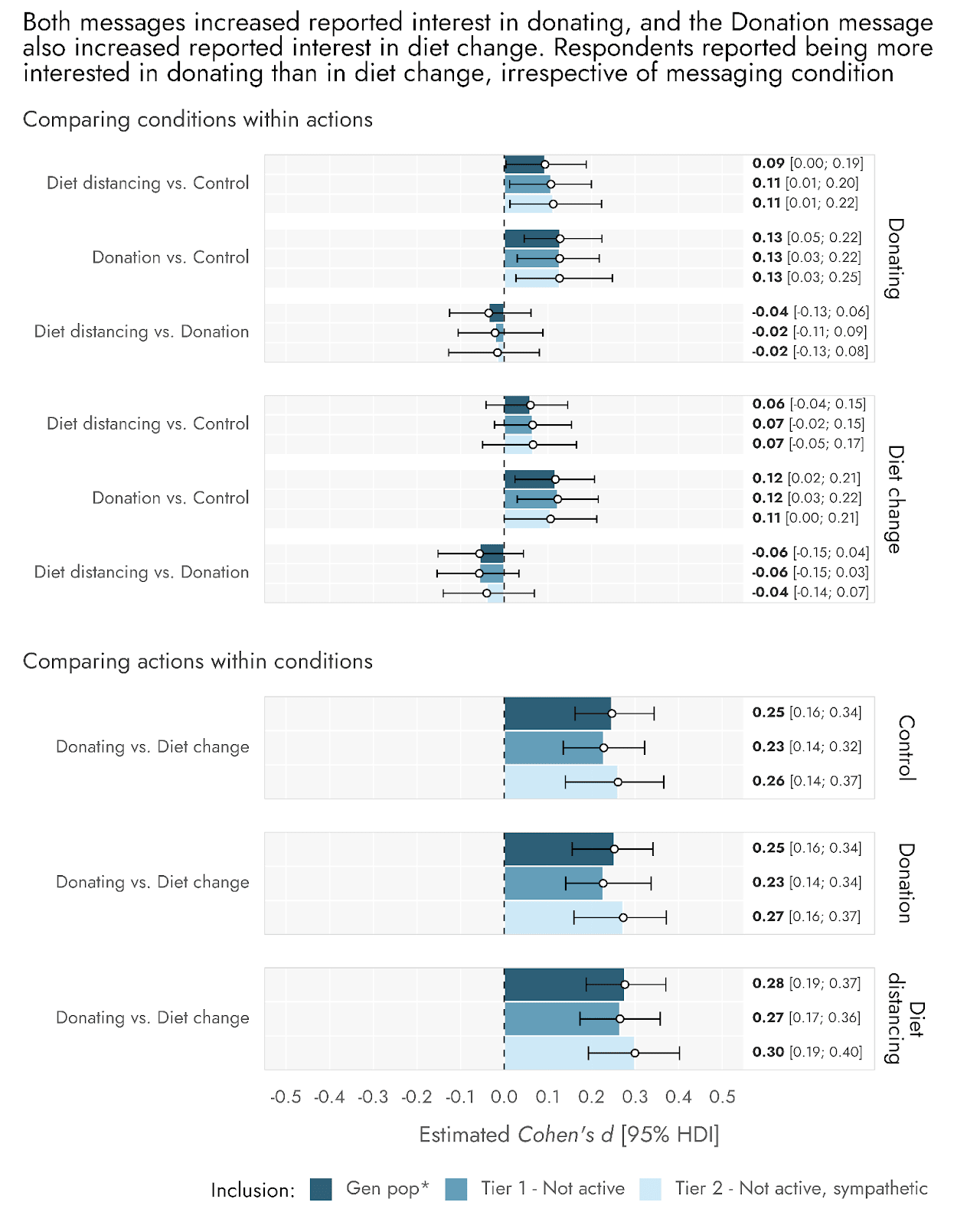

Both the Diet distancing and the Donation messages produced very small increases in the reported interest in making donations in the near future, with no reliable differences between them (Figures 12 and 13). Crucially, we did not find any negative impact of either message on interest in engaging in diet change. In fact, the Donation message even produced an increase, with a similar directional tendency observed in the Diet distancing condition. Regardless of messaging condition, there was a small but reliable preference for donating over diet change, in terms of reported levels of interest.

Figure 12: US adults were substantially more interested in donating than in diet change. Both messages boosted interest in donating, and the Donation message even slightly boosted reported interest in diet change

Figure 13: Both messages increased reported interest in donating, and the Donation message also increased reported interest in diet change. Respondents reported being more interested in donating than in diet change, irrespective of messaging condition

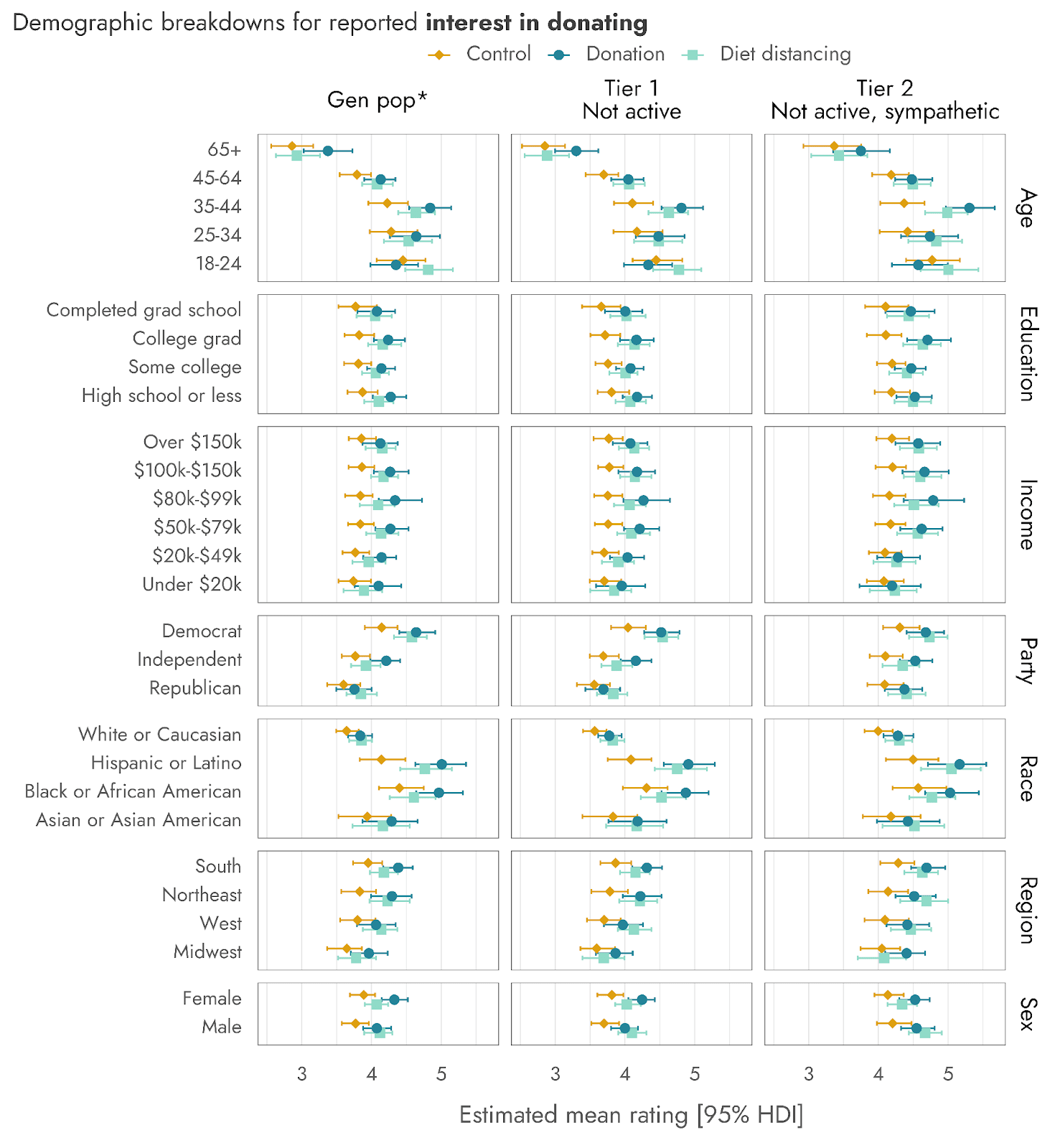

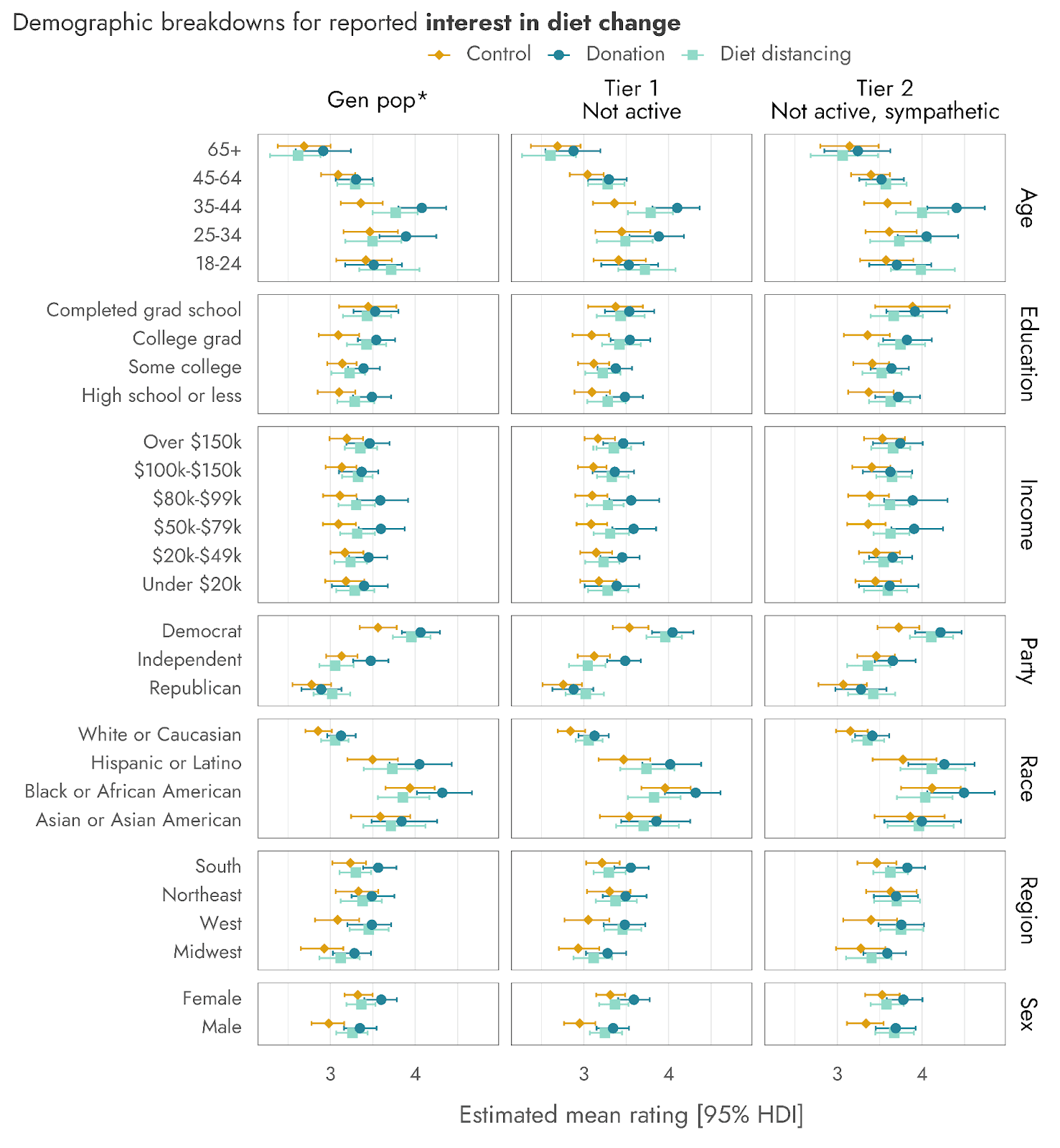

As with other outcome variables, demographic breakdowns can suggest plausible target audiences for messaging, and are shown in Figures 14 and 15. For both donating and diet change, interest tends to peak at ages 35-44, and drop - in some cases quite precipitously - in older and especially the oldest age bracket. Interestingly, the Control condition for donating does not show this peak, suggesting that the messages may activate a latent interest in the middle-aged groups that could be untapped. This may be especially interesting given those aged 35-44 tended to report lower difficulty ratings as well, and would be an age group more likely to have higher levels of disposable income that could plausibly be donated. A similar observation is in the racial demographic breakdown for donating. In general, Hispanic or Latino and Black or African American respondents tended to be more interested than other racial groups, and this interest seemed to spike in response to the Donation and Diet distancing messages, relative to the control condition.

Figure 14: Demographic breakdowns for reported interest in donating

Figure 15: Demographic breakdowns for reported interest in diet change

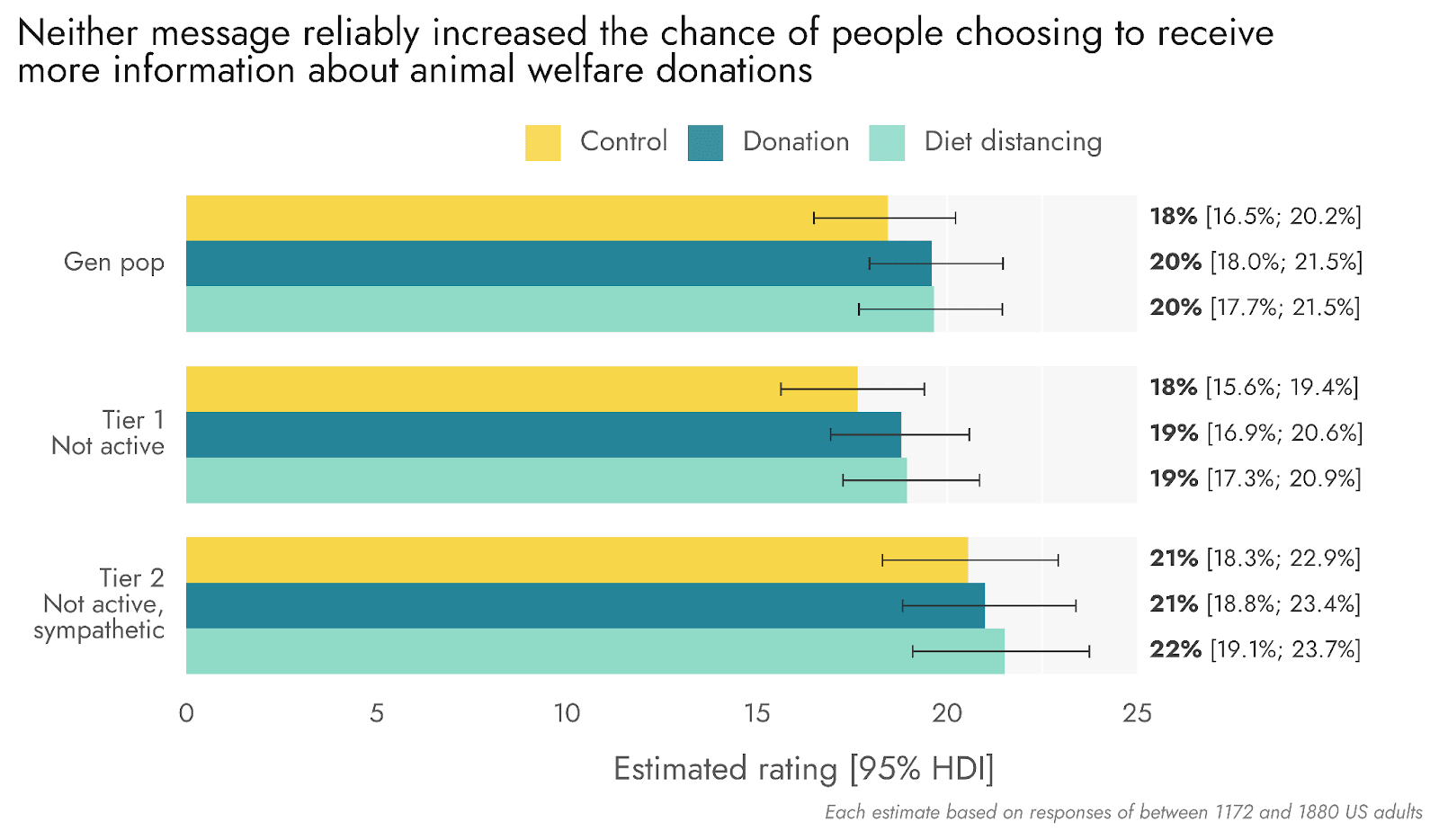

Did messages affect a donation-related behavior?

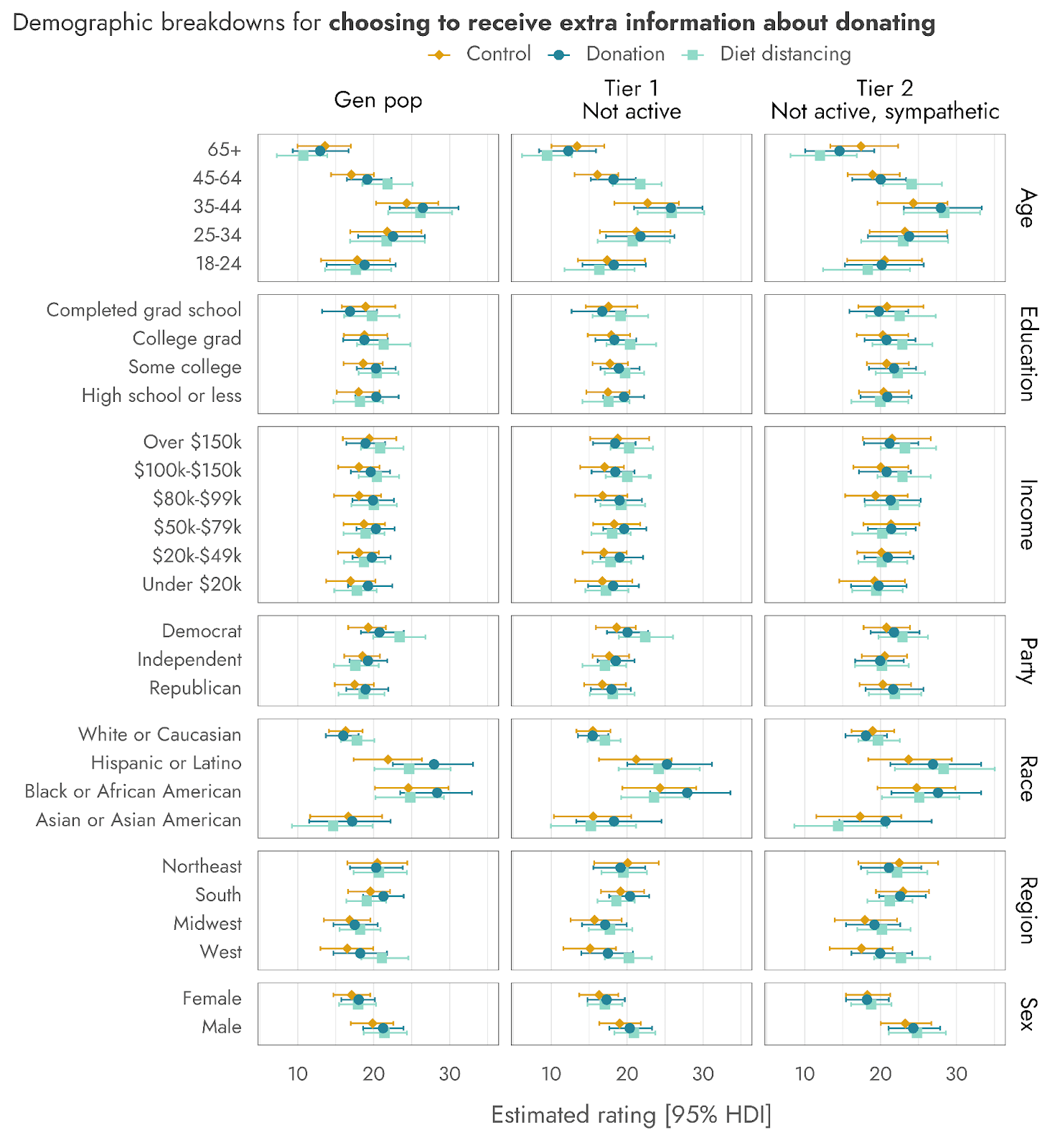

Although messages produced consistent changes across a range of relevant attitudinal markers, we did not observe any reliable increases in respondents choosing to receive additional information about making effective donations to farmed animals (Figures 16 and 17).

We do not interpret this null effect as evidence that messaging is irrelevant for donation behavior. Rather, responses to this outcome likely reflect stable predispositions (including simple curiosity, traits related to compliance, and general sympathy towards farmed animals) and contextual constraints of the survey environment (such as survey fatigue, or offers of information being perceived as spam or additional unpaid work). The survey context also captures people at an essentially random stage in terms of their intentions to donate (if any). Messaging in the real world may be targeted at people at particular stages of readiness or intention, making them more amenable to behavioral change. The messages developed in collaboration with FarmKind were not intended to mirror the exact messages the organization would deploy in practice. Rather, they were designed to balance persuasiveness while remaining minimally different from one another, and were presented as simple text without the visuals or calls to action typical of real-world campaigns. The offer of additional information was not designed to be persuasive, to avoid either unfairly pushing respondents to engage in uncompensated actions, or undermining the perceived independence of the survey among respondents.

A further consideration, which cannot be assessed with the outcomes we measured here, is that even if these messages perform similarly upon direct exposure, or do not substantially affect whether people choose to receive donation-related information, one message could be more surprising and therefore more shareable than the other. Outside of an experimental context, exposure to a message and opportunities to receive more information or to donate would not be randomly allocated, but would instead depend on factors such as organic spread driven by shareability or virality. These dynamics were not captured in the present experiment.

Figure 16: Neither message reliably increased the chance of people choosing to receive more information about animal welfare donations

Figure 17: Neither message produced an uplift in people choosing to receive extra information about effective donations

Figure 18: Demographic breakdowns for choosing to receive extra information about donating

Reflections from FarmKind on the findings

Findings were shared with FarmKind at several interim stages of data collection, as well as informally after all data had been collected. We have since reached out to FarmKind for further reflection on how they viewed the findings, and whether or not the findings affected their messaging or strategy. Aidan Alexander, Co-founder of FarmKind, shared the following:

- Donations as a promising ask: “Our understanding is that the study suggests that diet change is perceived as significantly more difficult than donating and equally impactful. Given that interest in donating is higher across all messaging conditions, we believe the movement should consider increasing the ‘share of voice’ for effective giving as a primary entry point for the public.”

- The ‘diet change elephant in the room’: “We were particularly interested in whether to explicitly distance donations from diet change (e.g., ‘You don't have to change what you eat to make a difference’). While we suspected this might lower defenses, the data shows the standard donation message was actually more compelling. This suggests that for direct conversion, ignoring the ‘elephant’ may be more effective.”

- Strategic implications (reach vs. conversion): “These findings have influenced our website messaging, with us avoiding referencing diet much on our home page. However, while explicit ‘diet distancing’ was slightly less compelling to the average respondent, it can still be the right choice in certain contexts. Often, addressing the ‘elephant in the room’ makes for a far more interesting story to podcast hosts and content creators and can reassure them that we're not going to alienate their audience by telling them to change their diet. When addressing the diet ‘elephant in the room’ can unlock orders of magnitude more reach, this can easily outweigh a small dip in conversion per person. We are encouraged to see that the study did not find that promoting donations crowds out interest in diet change; in fact, it may even slightly increase it.”

- ^

The exact number of respondents used in each analysis can vary, owing to non-usability or non-response for some questions, or splitting of respondents across different experimental conditions.

- ^

https://www.FarmKind.giving/

- ^

https://perma.cc/N2ZH-5ERU

- ^

The exact text for this was: “Would you like to receive a link to information about how to donate to the best charities working to fix factory farming? If Yes, then we can provide a link after you complete this survey. Selecting yes or no will have no effect on your participation in this survey, and the link will be provided outside of the survey, so it is purely for your own interest. We have not been paid for and do not benefit from linking to the website that we will provide you with a link to.”

- ^

Sample sizes for different inclusion tiers, discussed in the Inclusion subgroups section, varied slightly. Exclusion for already claiming to be vegetarian or vegan is an approximately 5% drop in sample size. Claiming to already donate is a drop of about 1% in sample size. Tier 1 is a 5-6% drop, and Tier 2 is a 26-28% drop.

Executive summary: Using Wave 2 of Rethink Priorities’ Pulse survey (≈5,600 US adults, Feb–Apr 2025), the report finds that a simple donation appeal was slightly more compelling than a “diet distancing” appeal, both messages modestly increased perceived impactfulness of donating without reducing perceived impact or interest in diet change, and neither message reliably increased a downstream “request more info” behavior.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.