We'll be posting results from this survey every day or two, since a few people asked us not to share all of them at once and risk flooding the frontpage. You can see the full set of results at our sequence.

This post is part of a series on Open Phil’s 2020 survey of a subset of people doing (or interested in) longtermist priority work. See the first post for an introduction and a discussion of the high-level takeaways from this survey. A previous post discussed the survey’s methodology. This post will present some background statistics on our respondent pool, including what cause areas and/or roles our respondents were working in or seemed likely to be working in.

You can read this whole sequence as a single Google Doc here, if you prefer having everything in one place. Feel free to comment either on the doc or on the Forum. Comments on the Forum are likely better for substantive discussion, while comments on the doc may be better for quick, localized questions.

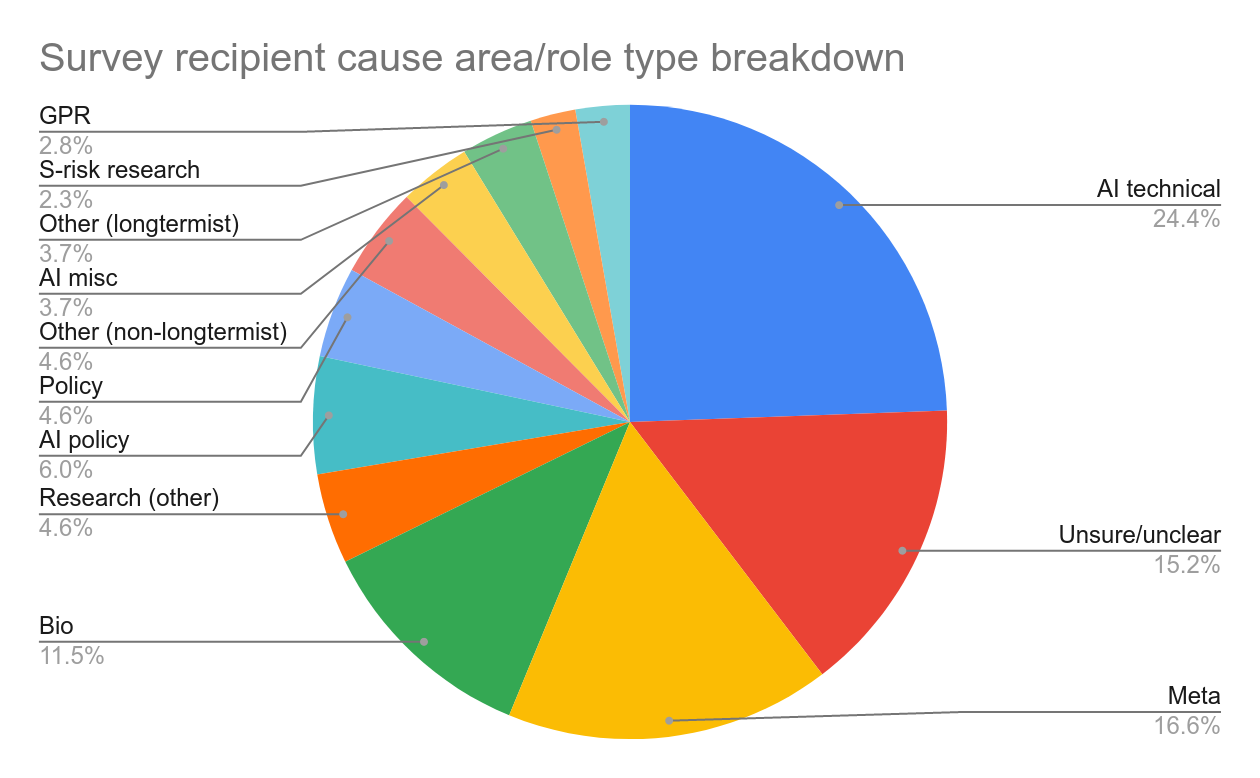

Cause Area/Role Type

We put respondents into rough buckets based on what type of work they seemed likely to shoot for in the medium term, according to our prior knowledge about them and their response to a survey question on career plans. This is just one of many possible bucketings.

Notes on these buckets:

- About 15% of our respondents had clear interest/experience in two or more cause areas. In these cases, I made a judgment call about which bucket they should go into (including “unsure/unclear”) which I often felt was pretty arguable.

- The “unsure/unclear” bucket is mostly of people for whom we were unsure of the type of longtermist-motivated work they would do, but also includes some people for whom we were unsure whether they would end up doing any type of longtermist-motivated work. One reason that this bucket is so large is that our recipients were, on average, fairly young.

- The “Policy” bucket indicates work that is related to government policies on a fairly broad range of longtermist-flavored topics. “AI policy” indicates, as you’d expect, work focused on policies related to AI in particular. It also includes some work related to private-sector policy.

- “AI misc” indicates work related to AI that does not fall into the “AI technical” or “AI policy” bucket — for example, AI forecasting work and people who work at AI labs but don’t fall into any of the other AI categories.

- “Meta'' here mostly indicates work related to growing and improving the effectiveness of the set of people who work on EA and longtermist issues, but also includes work related to increasing the amount of money directed at these issues. It includes EA community-building and rationality community-building. Although the term is often also used to include research on what EA’s high-level priorities should be, I don’t intend that usage here. In my bucketing, those types of work fall under “GPR” and “Research (other).”

- “GPR” ((theoretical) global priorities research) here refers to research associated with Forethought and GPI.

- “Research (other)” consists of “macrostrategy research” and other research from a zoomed-out perspective that does not fall into the GPR bucket. This bucket consists mostly of people associated with FHI or Open Phil.

- The difference between “Other (longtermist)” and “Other (non-longtermist)” is my assessment of the motivation for the work, not our assessment of its consequences.

Education

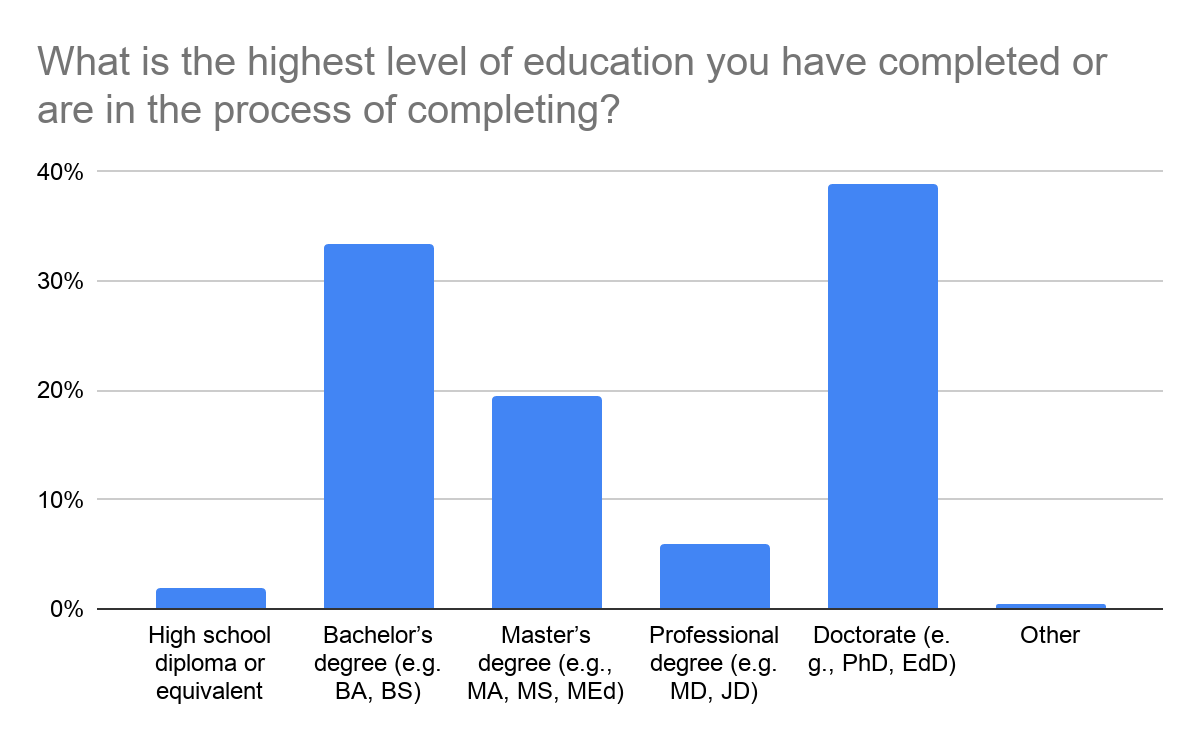

We asked our respondents various questions about their educational backgrounds, starting with a question about the highest level of education they have completed or were in the process of completing.

39% of our respondents reported that they held or were in the process of completing a doctorate.

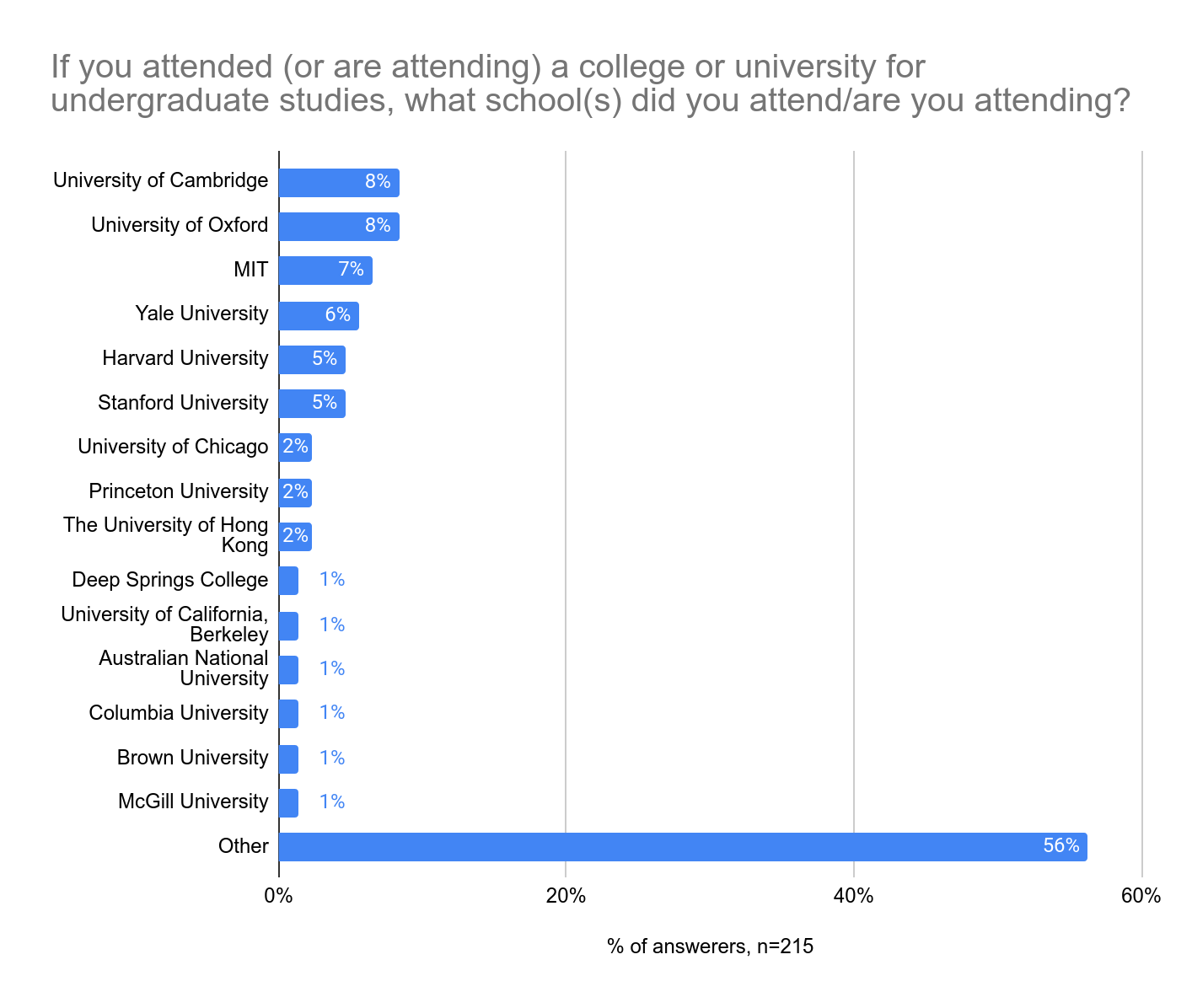

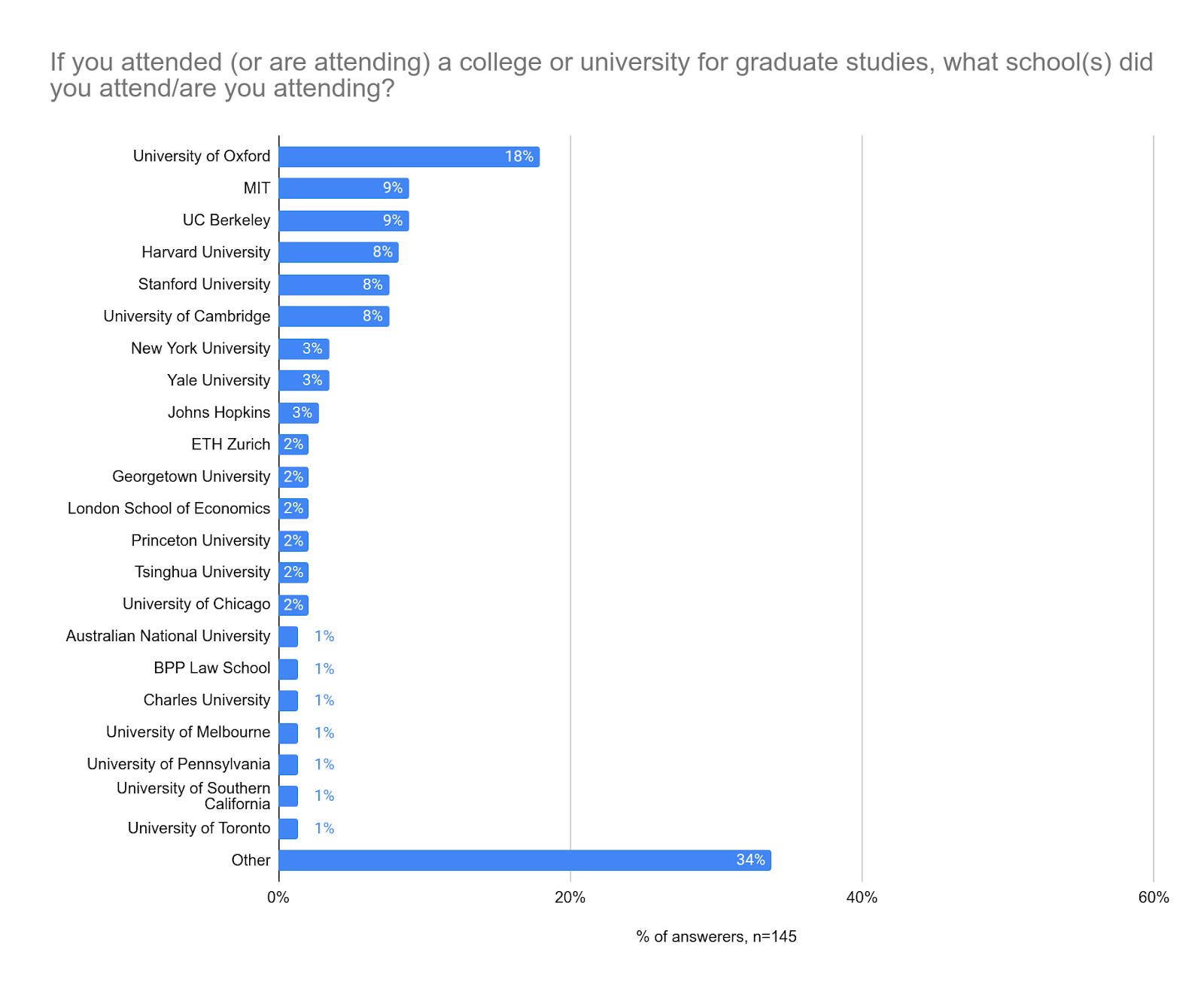

Below is the breakdown of respondents’ graduate and undergraduate institutions. (Note that the numbers add to more than 100% because some people attended multiple undergraduate or multiple graduate institutions.)

Note that Oxford’s popularity for graduate studies among our respondents is likely influenced by the fact that FHI and GPI are housed there.

61% of our respondents had studied or were studying (undergraduate or graduate) at one of the top 15 universities in the world, according to this list[1]. When counting by weight rather than by raw number, the figure is similar. The corresponding undergrad-only figures were both 44%[2].

68% of our respondents by raw number, and 75% by weight, reported studying or having studied a STEM subject at either the undergraduate or graduate level. (This is according to a definition of STEM which includes biology, engineering, and computer science, but not economics.) This looks similar-to-slightly-greater-than the results from the 2019 EA Survey, which gives between 60% and 70% for people studying STEM (depending how their “Other Sciences” category further breaks down).

From my very shallow (10 minutes) of research on this question, both our and the EA Survey’s respondents look substantially more STEM-y than elite US college students in general; Harvard University undergraduates were ~45% STEM majors in 2015 (source).

It’s interesting to note that the numbers of respondents who did their undergrads at MIT and at Oxford/Cambridge are similar (7% for MIT, 8% for both Oxford and Cambridge), despite the fact that the total number of undergrads at these universities differ by a factor of three. MIT had just ~4,500 undergraduates in 2019, while Oxford and Cambridge each had about ~12,000. This means that the rate of being a survey respondent is ~2x higher for MIT undergrads than for Oxbridge undergrads. Yale has a rate similar to MIT’s, while Harvard and Stanford have rates similar to Oxbridge’s.

The 2019 EA Survey’s analysis of where its respondents went to undergrad has Oxford and Cambridge much further in the lead. Presumably this difference is somehow caused by our selectivity, who we happen to know, and/or by our focus on longtermists, since those are the main differences between the two respondent pools. But I’m not sure what the mechanism is.

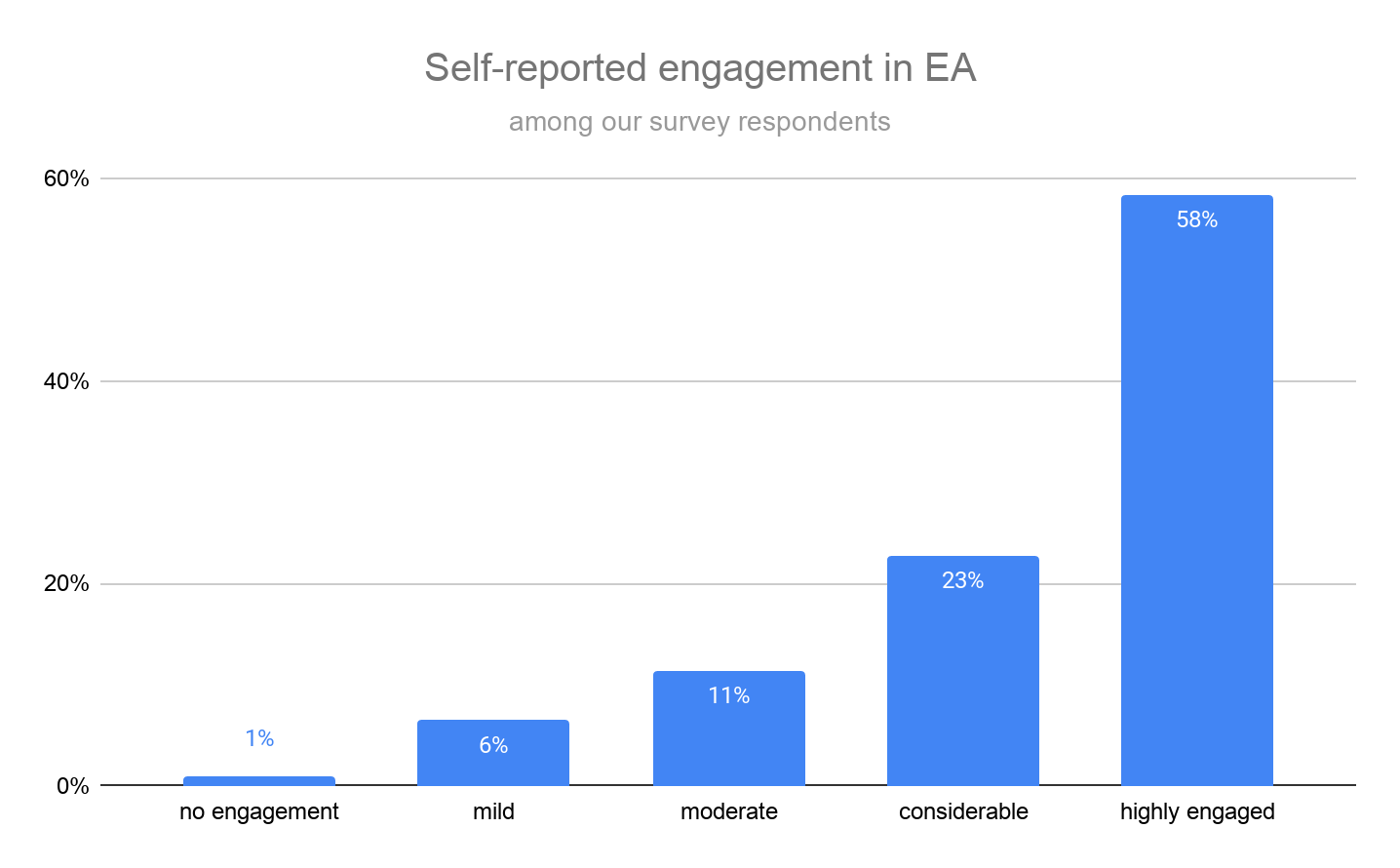

Self-Reported EA Engagement Level

We asked “On a scale of 1-5, how engaged do you consider yourself to be with effective altruism and the effective altruism community?” and gave the following response options.

- No engagement: I’ve heard of effective altruism, but do not engage with effective altruism content or ideas at all.

- Mild engagement: I’ve engaged with a few articles, videos, podcasts, discussions, events on effective altruism (e.g. reading Doing Good Better or spending ~5 hours on the website of 80,000 Hours).

- Moderate engagement: I’ve engaged with multiple articles, videos, podcasts, discussions, or events on effective altruism (e.g. subscribing to the 80,000 Hours podcast or attending regular events at a local group). I sometimes consider the principles of effective altruism when I make decisions about my career or charitable donations.

- Considerable engagement: I’ve engaged extensively with effective altruism content (e.g. attending an EA Global conference, applying for career coaching, or organizing an EA meetup). I often consider the principles of effective altruism when I make decisions about my career or charitable donations.

- High engagement: I am heavily involved in the effective altruism community, perhaps helping to lead an EA group or working at an EA-aligned organization. I make heavy use of the principles of effective altruism when I make decisions about my career or charitable donations.

The wording of the question and response options was identical to what was used in the 2020 EA Survey — we synchronized these to allow for an apples-to-apples comparison of the results. Around 7% of people did not give an answer for this question.

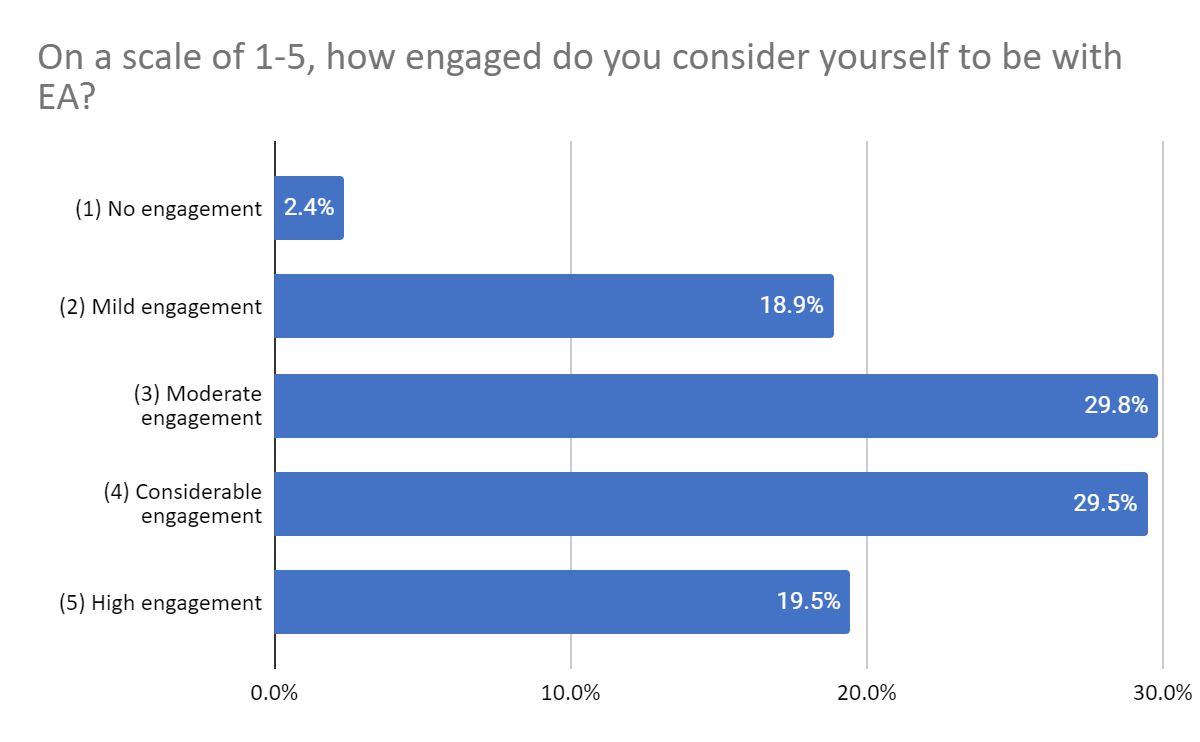

Here is the equivalent graph from the 2020 EA Survey for comparison.

Our respondents are much more engaged, which makes sense, because our selection process selected for more engaged people.

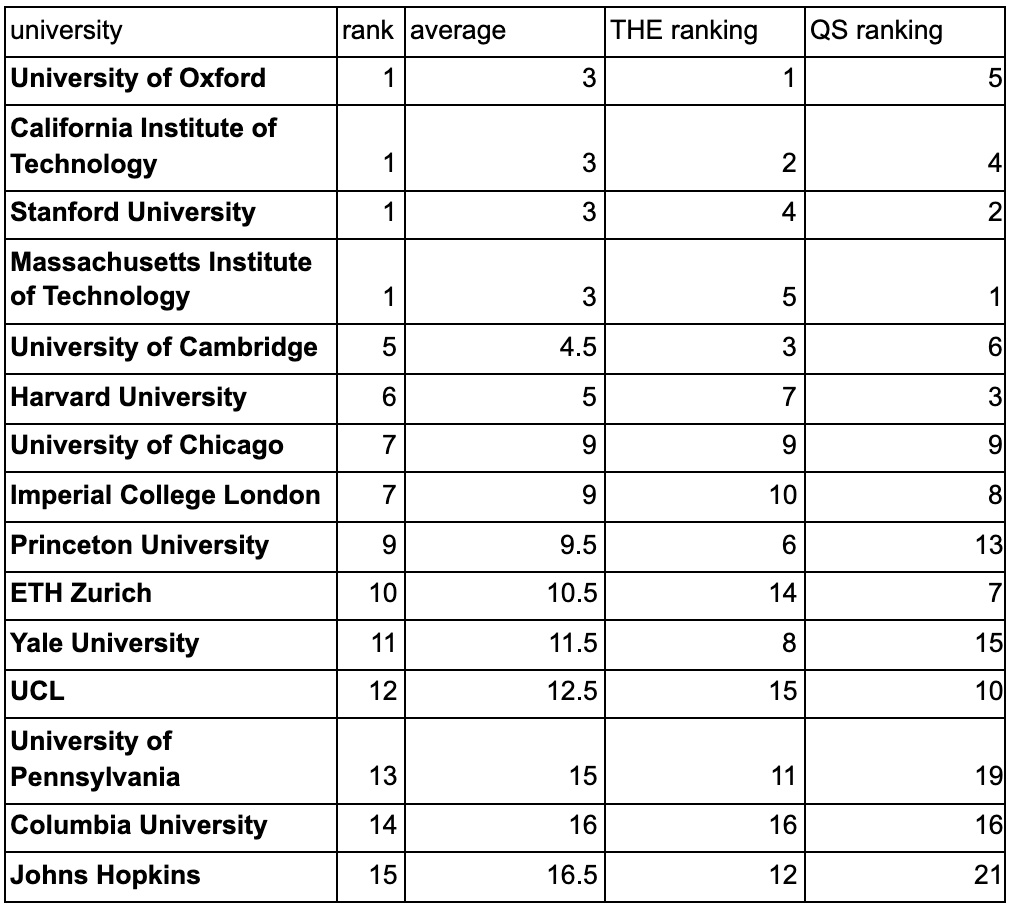

Appendix: Top 15 Universities

To come up with a list of “top 15 world universities” for the purposes of this analysis, we averaged the QS rankings for 2019 and THE rankings for 2020. Here is our list.

These rankings don’t include institutions like liberal arts colleges that offer only an undergrad degree program, so our list is missing them.

Any such list is quite arguable, but it doesn’t look like there are small modifications to this list that would significantly change the 61% figure, since the schools the most EAs have attended are already near the top of any such list. Including UC Berkeley on the top-15 list is the most meaningful single change that’s plausible, and would increase it to 66%. ↩︎

The 2019 EA Survey gives approximately 15% for the percentage of its respondents who did their undergrad at a top-15 university according to our list. (I use data from the 2019 Survey here because the 2020 Survey doesn’t ask the question this specifically.) ↩︎