Summary

- We hired 31 people for our current Summer Research Fellowship, out of 631 applications

- The applications were of impressive quality, so we hired more people than expected

- We think we made several mistakes, and should:

- Communicate more clearly what level of seniority/experience we want in applicants

- Have a slightly shorter initial application, but be upfront that it is a long form

- Assign one person to evaluate all applicants for one particular question, rather than marking all questions on one application together

Hiring round processes

The Existential Risk Alliance (ERA) is a non-profit project equipping young researchers with the skills and knowledge needed to tackle existential risks. We achieve this by running a Summer Research Fellowship program where participants do an independent research project, supported by an ERA research manager, and an external subject-matter expert mentor.

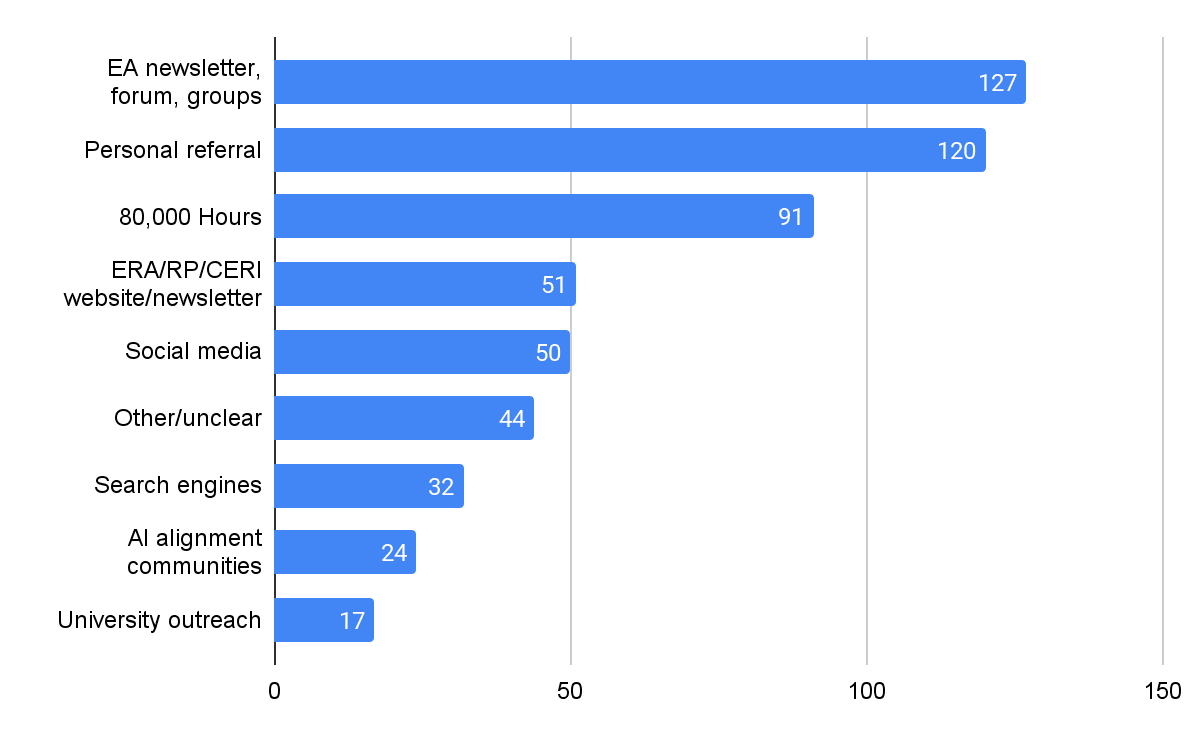

Promotion and Outreach

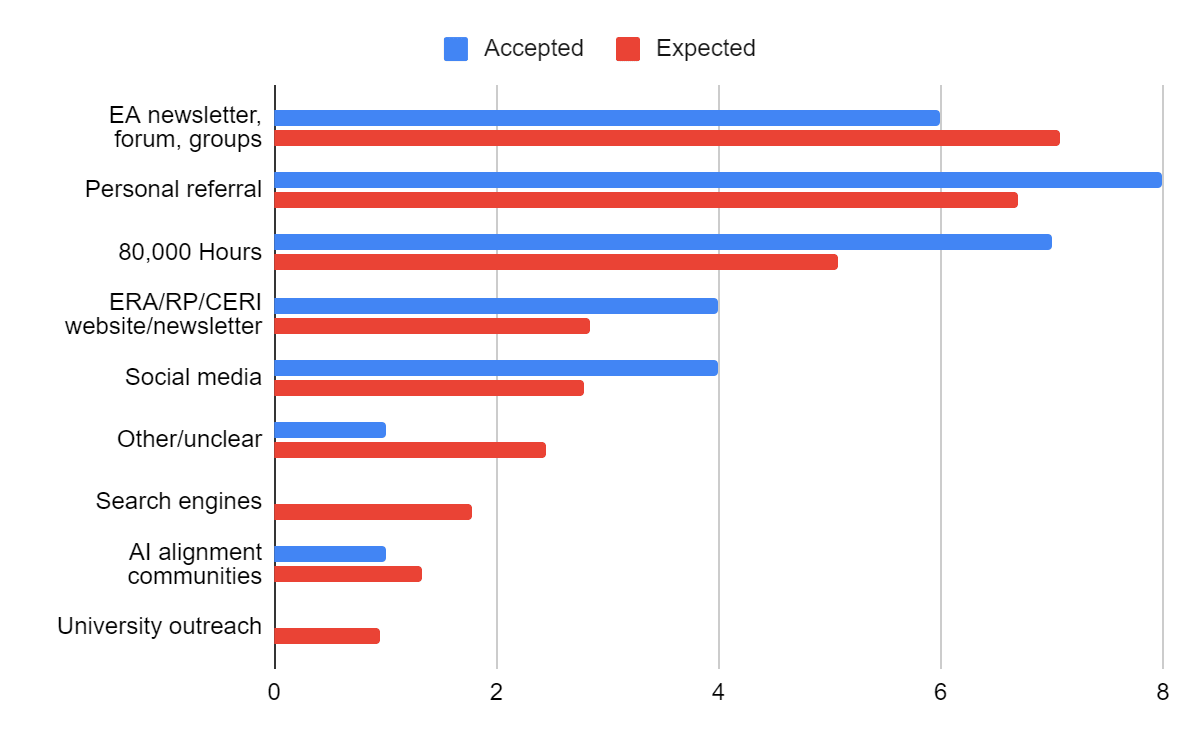

We tried quite hard to promote the Fellowship. Personal connections and various EA community sources were the most common referral source for applications:

Initial application

Our initial application form consisted of submitting a CV (which we put minimal weight on) and answering various open-ended questions. Some questions on motivation, reasoning ability, and previous experience were the same across all cause areas, and we also asked some cause area-specific subject matter questions. Our application form was open for 22 days, and we received a total of 631 applications from 556 unique applicants (some people applied to multiple cause areas). There was significant variation in the number of applications in each cause area: AI Gov = 167, AI Tech = 127, Climate = 100, Biosecurity = 96, Misc & Meta = 86, Nuclear = 51.

People tended to apply late in the application period, with more than half of applications arriving within three days of the deadline.

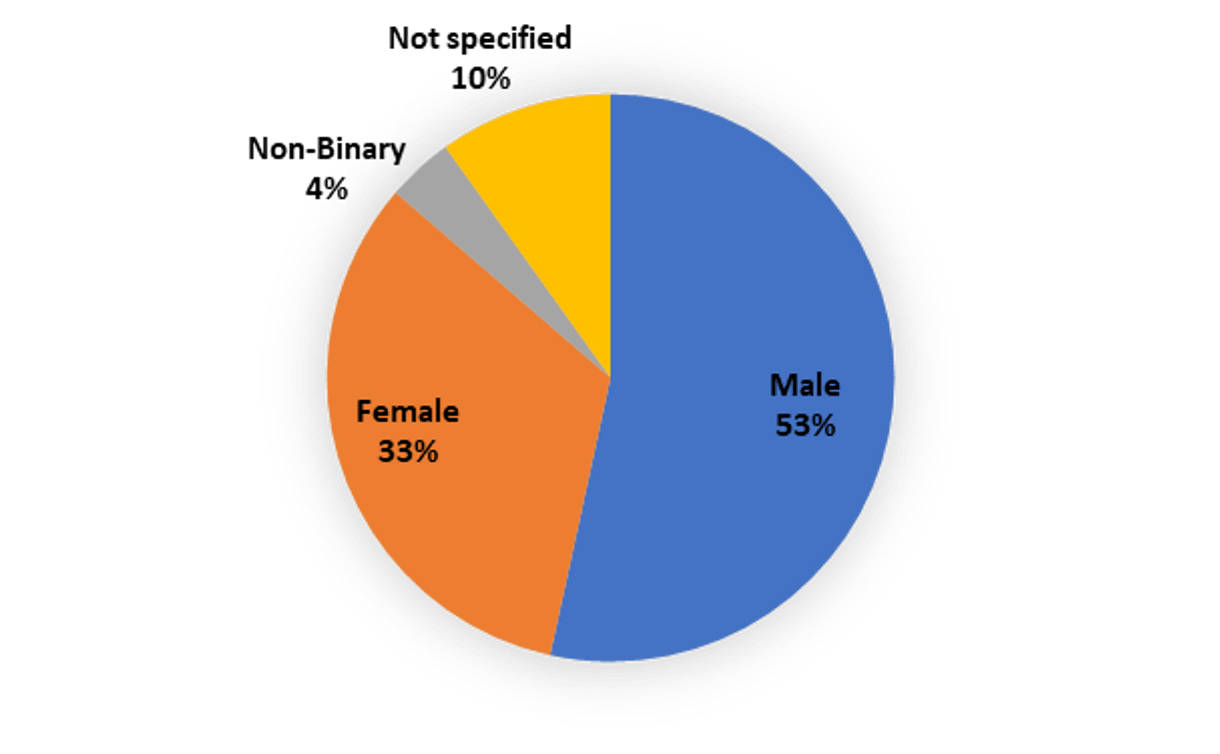

The majority of applicants were male:

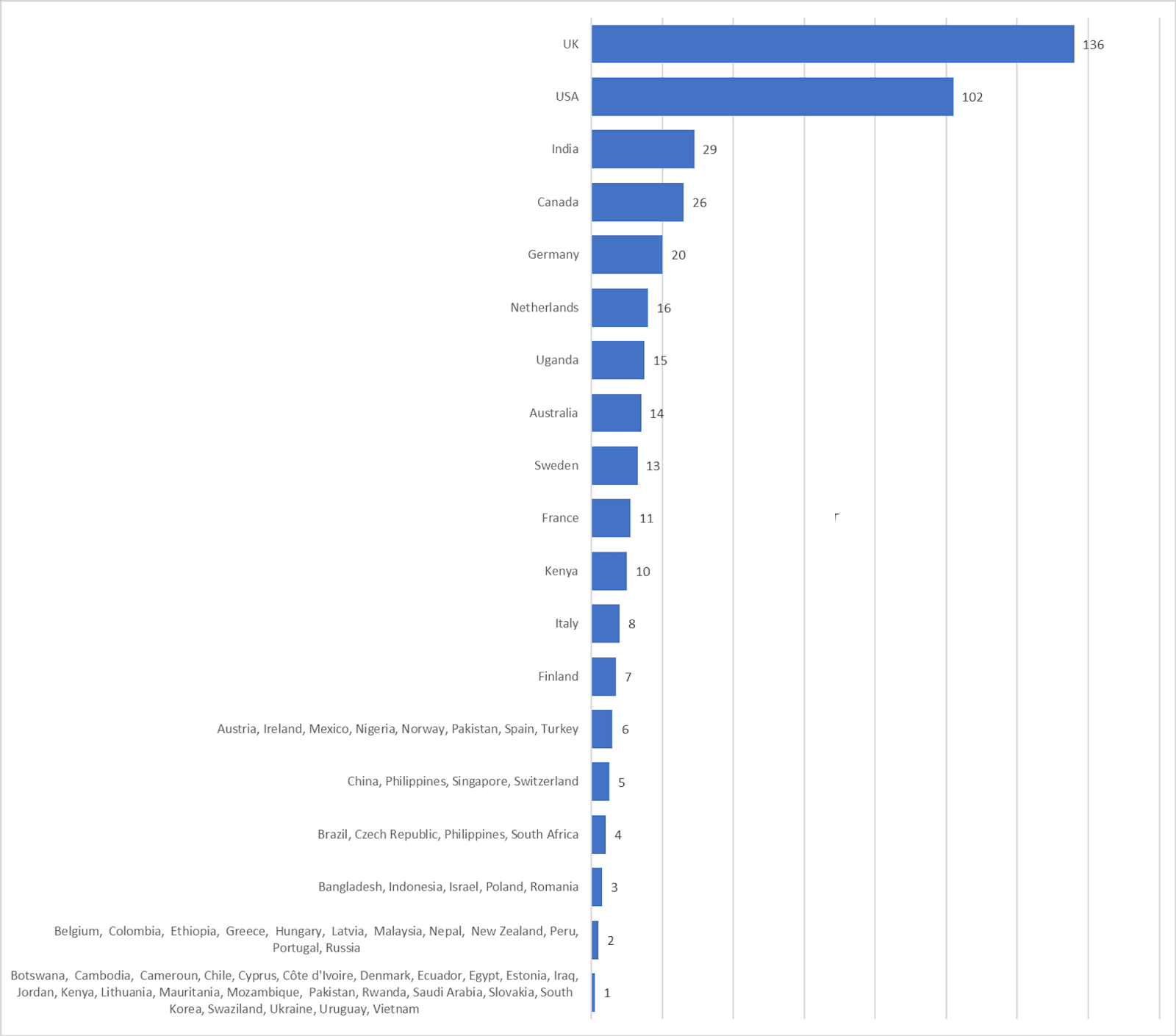

And the UK and US were by far the most common countries of residence for applicants:

Interviews

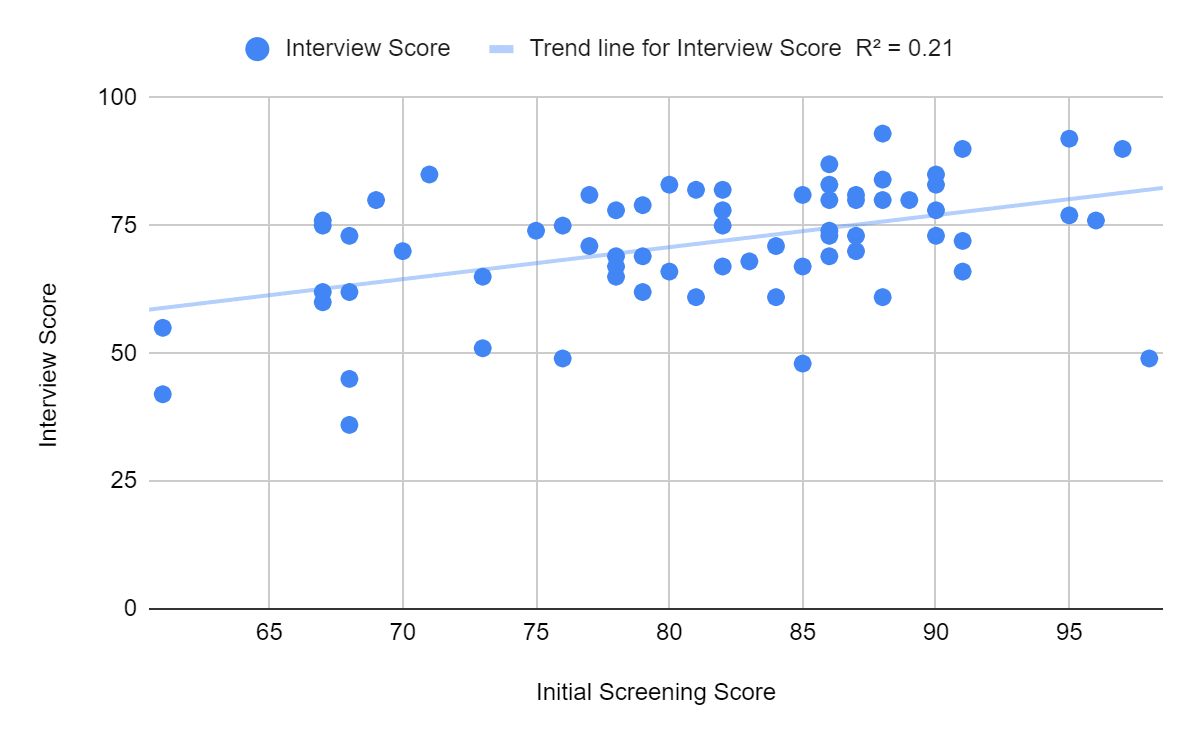

After assessing the written applications, we invited 80 applicants (13%) for an interview as the second part of the recruitment process. Interviews were conducted by the research manager of the cause area the person was applying to, and lasted around thirty minutes. We used structured interviews, where each cause area had a standard list of questions that all interviewees were asked, to try to maximize comparability between applicants and improve fairness. Interview questions sought to gauge people’s cause-area-specific knowledge, and ability to reason clearly responding to unseen questions. Even though only the people who did best on the initial application were invited to interviews, there was some positive correlation between initial application and interview scores. If this correlation was very strong, that would be some reason not to do an interview at all and just select people based on their application. This was not the case: the interview changed our ordering of applicants considerably.

Composition of the final cohort

We had initially projected to fill approximately 20 fellowship spots, with an expected 3-4 candidates per cause area. We aimed to interview at least three times the number of candidates as the positions we planned to offer, to improve our chances of selecting optimal candidates.

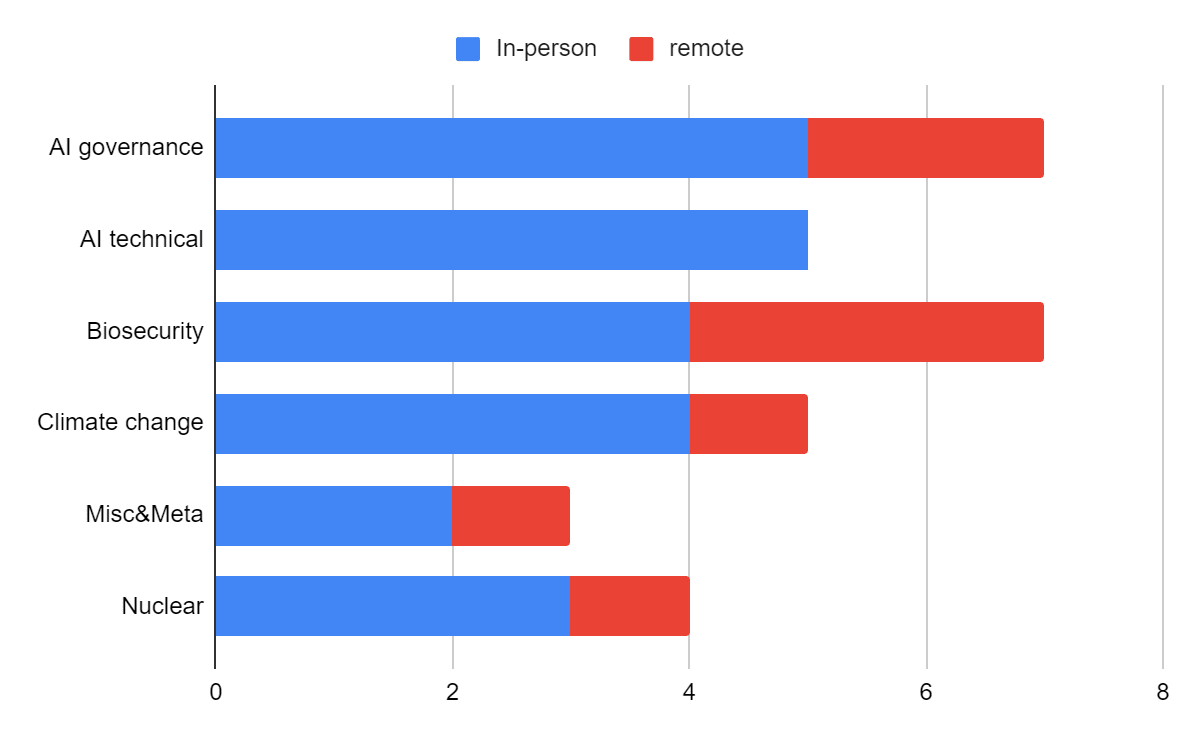

Because of the large number of excellent applications, we decided to open our fellowship to remote candidates that we couldn't host otherwise. Within cause areas, we selected candidates roughly based on a weighted average of their initial application, and interview (with a 5:3 ratio of weights for application:interview, given the application was far longer than the interview). Because scores were not directly comparable between cause areas, we subjectively assessed application quality between cause areas to decide on the number of spots per cause area. We accepted 31 fellows (39% of interviewees, 5% of applicants).

The number of fellows accepted from each referral source matched fairly closely with what we would expect when simply scaling the number of applicants received from that source by the acceptance rate:

In terms of demographics, the final cohort has 16 males, 13 females, and 2 unspecified or non-binary people. Ten fellows are from the US, nine from the UK, and all other countries had no more than two.

Key takeaways

Things to change

- Be clearer about who we want to apply

- Several under-18s applied who it would have been legally difficult for us to hire, so we should have made this age requirement clearer.

- We deemed several applicants to be over-qualified, so we should have specified better who this program would be most valuable for.

- However, there are several counter-arguments, so we think this balance isn’t obvious:

- It is hard to communicate exactly who is under/over-qualified, and people will interpret things differently, so perhaps it is best just to maximise the number of people who apply, and we can filter as we see fit.

- For some applicants, participating in our application process may be valuable in itself, to get them thinking more about X-risk.

- Be more transparent about the length of the application form, and make it shorter

- We asked people to spend no more than two hours on the application form, but this was unrealistic and a mistake on our end. Of 17 fellows who responded to a survey we sent out, the average length of time they self-reported spending on the initial application was 6.8 hours (standard deviation 5.8 hours; minimum 1 hour; maximum 20 hours). On a five-point scale from the application being ‘much too long’ to ‘much too short’, nine respondents felt it was ‘slightly too long’ and eight thought it was ‘about the right length’.

- A shorter application would also mean less work for us when reviewing them.

- Conversely, we think most of our questions were quite appropriate for selecting the best candidates, so we probably would only slightly shorten it next time.

- We may also introduce a second stage to the application process to reduce the length of the initial application but still cover the whole range of questions for people we consider more closely.

- Evaluate applications one question at a time (rather than one applicant at a time)

- If one person marked all ~600 Q1s, a second person marked all ~600 Q2s and so on, this would reduce scoring incongruities between different evaluators.

- It could also remove some biases if a marker likes/dislikes previous answers and wants to score the current answer for that applicant similarly.

- This would require marking all applications after the deadline, rather than on a rolling basis.

- Our hiring software did not allow this, so we may change it next year.

- Run the application process earlier, to take pressure off legal/visa/travel things and allow for better outreach and promotion to potential candidates

- This would also help people who had competing (sometimes exploding) offers.

- Conduct a mock interview with another team member before the real interviews start

- This would be especially useful for people who haven’t conducted interviews before, as it could make the process more familiar and comfortable before interviewing applicants.

- This would also be an opportunity to re-check that the questions are crisp and understandable, as fixing questions after the first real interview is problematic for standardisation.

- Use a form that prevents people from submitting answers longer than the word limit

- Deciding on penalties after reading an answer that was too long was difficult, time-consuming and noisy.

- Avoid emails we send applicants going to spam 🙁

- Our rejection email included lots of links to other opportunities and resources, but this caused it to be marked as spam for some applicants, who then thought we had simply not responded to them. We will communicate more clearly with applicants about this possibility next time, asking them to check their spam folder (and we will attempt to prevent emails going to spam in the first place).

Things to celebrate

- We processed applications quickly: 16 days from the application deadline to sending out offer letters

- We also provided an expedited review to all promising applicants who requested it.

- We provided feedback on their application to 19/23 people who requested it, from fairly short written feedback to applicants rejected at the first stage, to occasional calls with rejected interviewees.

- We also passed on some candidates to other fellowships and programs, which may have been quite valuable.

- Feedback we received from applicants was generally positive, especially about the interviews being comfortable, and the fast turn-around.

- We received so many great applications! Lots of people want to work in X-risk reduction.

- Compared to the existing research field, and to past iterations, males were a smaller majority of all applications and of the most promising applicants.

Things to ponder

- This year there were some small interactions between our hiring processes and related programs (CHERI, SERI MATS, UChicago Xlab) where we forwarded candidates to them, but quite possibly there are better, more substantive ways to coordinate applications.

- We decided against asking applicants what they would do in the summer if rejected from ERA, as we didn’t want to provide a perverse incentive for applicants to appear to have worse alternative options.

- However, perhaps preferentially giving places to people without other great alternatives would increase our counterfactual impact.

- About a third of our final cohort are from the US and UK respectively, and arguably increasing the geographic diversity of the X-risk field would be valuable. We are unsure how best to address this going forward.

- Some fellows live in Cambridge already, so we should consider whether offering them an in-person fellowship is best, or whether we should invite them to be ‘remote’ (with the option to sometimes work in the office) and free up a spot for someone who wouldn’t otherwise be in Cambridge.

- For some applicants, their actual career plans and aspirations differ from the cause area they are in for the fellowship (sometimes people applied to multiple causes but were only accepted in one). We are unsure how best to handle this.

Thanks for reading, we are keen to hear from you with any thoughts and suggestions! As well as commenting here, you can email me at oscar@erafellowship.org or submit to our (optionally anonymous) feedback form here.

You might want to look into range restriction. You can dive deep into via Range Restriction in employment interviews: An influence too big to ignore. But if you just want the simple explanation: correlation is artificially lowered when you only sample the people that pass the initial screen, making the interview appear less effective than it really is. So it is possible (likely?) that you could reasonably not do an interview at all.

I think you are roughly correct: the chapter is mainly about using statistics to correct for range restriction.

My interpretation/takeaway (and my memory from reading this paper a while back) is that many selection methods are less predictive than we think due to using a pre-selected sample (the people that passed some other screen/test). I wish I had some easy actions that a hiring manager could take, but I'm afraid that I don't. I only have vague concepts, like "be more humble about your methods" and "try not to have too much confidence that you have a go... (read more)