Context

The Biosecurity Fundamentals: Pandemics Course, run by BlueDot Impact, is a programme that teaches biosecurity and its role in preventing, detecting, and responding to catastrophic pandemics. I joined the first cohort and have greatly benefitted from the course materials and meaningful discussions. Through the course, I became interested in biosecurity technologies and their applications in public health interventions in Malaysia (where I am from) and Southeast Asia.

One of the technologies I am most excited about is far ultraviolet-C radiation (far-UVC, 200-230 nm). Far-UVC is effective in inactivating pathogens and poses a lower risk to skin and eyes than longer wavelength UV radiation. While more research is needed on long-term exposure effects, it remains a promising tool for indoor air quality (IAQ) and pandemic prevention.[1]

As part of the 12-week virtual course, we worked on projects to apply our knowledge in biosecurity. Given the importance of far-UVC in IAQ and pandemic preparedness, I chose to promote federal policy changes for IAQ in the United States, aiming to apply this knowledge in Southeast Asia.

My teammates and I planned to conduct secondary research, draft policy recommendations, develop a cost-benefit analysis, create a communications plan, and engage local policymakers. However, through conversations with experts, we realised that federal policy changes require long-term lobbying and resources beyond our project’s scope. We then shifted to producing an editorial to educate specific audiences on the importance of IAQ for public health and pandemic preparedness.

I, Chloe Lee, wrote this report. I thank @Richard Bruns, Leah Goodman, and Zainab Khambaty for their discussions and feedback. However, this does not mean that they necessarily agree with the arguments or observations presented in this report. Any mistakes are my own.

Theory of Change

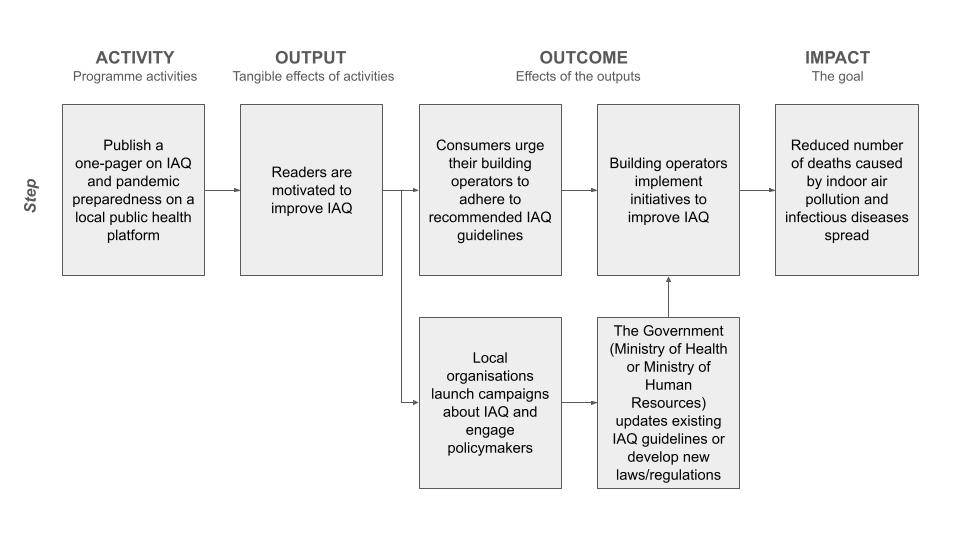

My editorial aims to raise awareness among Malaysians about the importance of IAQ for public health and pandemic protection, motivating behavioural change. It presents the latest research on IAQ's impact on health and safety and interventions against air pollutants, including pathogens. The theory of change posits that increased awareness will lead to improved indoor infrastructure and the development of new laws and regulations.

Limitations

I was uncertain about the effectiveness of an editorial in changing IAQ policy and practices in Malaysia. Policy change in Malaysia is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and influenced by the current political party (see Overview of IAQ Regulations and Public Health in Malaysia). A single editorial is unlikely to result in significant policy change, thus more sustained efforts are needed. Additionally, I struggled to find suitable online platforms to publish the editorial that would reach key decision-makers in IAQ. After several expert interviews, I connected with a senior researcher at Malaysia’s National Poison Centre (NPC), which publishes information and organises events about drug and poison management. At the time, NPC was the most feasible option for publication.

With more time, I would consult more experts and organisations in public health policy to better understand the impact of an editorial and identify more effective publishing venues.

Methodology

The editorial is based on findings from two expert interviews and secondary research. The expert interviews were conducted in an explorative, unstructured manner to understand Malaysia's public health and IAQ policy landscape. Experts included a senior researcher at a local think tank, a veteran IAQ activist and medical doctor, and a senior researcher at NPC Malaysia, all sourced through personal connections. Secondary research sources included peer-reviewed scientific journals and grey literature, such as press announcements and government reports.

Results

Editorial on improving IAQ in Malaysia

An editorial highlighting recent academic findings on improving IAQ for local authorities was produced. The key points are as follows:

- The amount of air pollutants can be 2 to 5 times higher indoors than outdoors. In Malaysia, people typically spend 70-80 per cent of their time indoors, a figure that has increased following the COVID-19 pandemic. Keeping indoor air pollutants within recommended limits is crucial.

- Poor indoor air quality harms the most vulnerable—infants, children, adults with weakened immune systems, and elderly with health conditions. When exposed to air pollutants, school children in Malaysia suffer from cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath.

- Readers are advised to speak to local building operators at healthcare facilities,

residential, and non-residential settings about filtration, ventilation, and disinfection, to effectively protect themselves from harmful indoor air pollutants and improve public health in Malaysia.

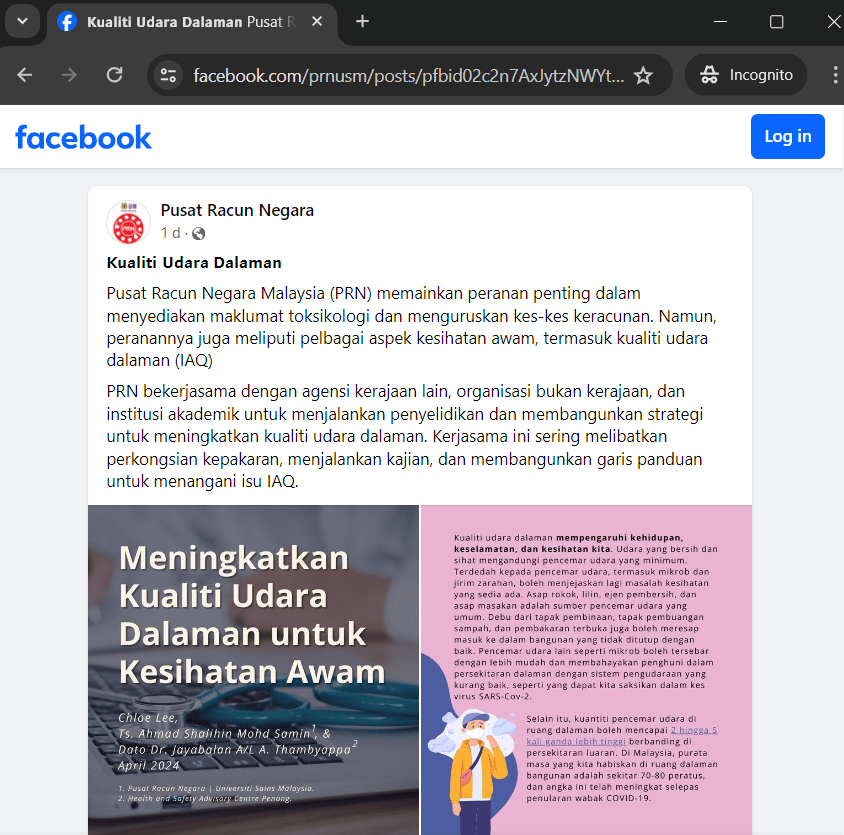

I collaborated with the senior researcher at NPC Malaysia to review and translate the editorial into the local language. The editorial was published on the official website of NPC Malaysia and their Facebook and Instagram accounts on 23 May 2023.

Link to the editorial: Improving Indoor Air Quality for Public Health - English.pdf

Infographics on the NPC’s Facebook and Instagram (in Bahasa Melayu)

Translation: The National Poison Centre (Pusat Racun Negara, PRN) plays an important role in providing toxicological information and handling poison cases. However, its role also covers various aspects of public health, including indoor air quality (IAQ).

PRN collaborates with other government agencies, non-governmental organisations, and academic institutions to research and develop strategies to improve indoor air quality. This collaboration often involves sharing expertise, conducting studies, and developing guidelines to address IAQ issues.

Overview of IAQ Regulations and Public Health in Malaysia

In Malaysia, IAQ falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) within the Ministry of Human Resources. The Code of Practice on Indoor Air Quality, enacted in 2005, was replaced by the Industry Code of Practice on Indoor Air Quality in 2010.[2] This document outlines employer responsibilities for investigating IAQ issues, implementing controls, providing training, and maintaining records in workplaces. It also sets acceptable limits for indoor air contaminants like respirable particulate, formaldehyde, bacteria, and fungi.

In 2021, DOSH and the Ministry of Health published the Guidance Note for Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) during Pandemic COVID-19, based on recommendations from The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).[3] This guidance details ventilation requirements for healthcare facilities and public, residential, and commercial settings. Despite these guidelines, both public and private sectors in Malaysia prioritise outdoor air quality over indoor air quality. There are no enforceable IAQ laws or regulations, and public discussions about IAQ laws are lacking. The Department of Environment regularly publishes reports on air pollution and the air quality index. Non-profits like the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Greenpeace have commissioned studies on the health and economic impacts of ambient air quality in Malaysia.[4]

An expert interview with a public health think tank in Malaysia highlighted the multiple factors necessary for public health policy change, including political will, advocacy, lobbying, coalitions, and financial investment. The complexity of policy change is exemplified by The Control of Tobacco Product Regulations, which required persistent advocacy, lobbying, and coalitions among various stakeholders. Reaching a consensus on tobacco controls was challenging due to the conflicting interests of vested interest groups and public health advocates. The interviewee noted that while business groups may resist improvements due to various concerns, the government should prioritise public health and strive for optimal public health outcomes without necessarily achieving full consensus. For effective policy implementation, formal laws and regulations need to be enacted. Currently, the Industry Code of Practice on Indoor Air Quality 2010 is not enforceable and is rarely followed by local developers and building operators.

- ^

Ernest R. Blatchley III, David J. Brenner, Holger Claus, Troy E. Cowan, Karl G. Linden, Yijing Liu, Ted Mao, Sung-Jin Park, Patrick J. Piper, Richard M. Simons & David H. Sliney (2023) Far UV-C radiation: An emerging tool for pandemic control, Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 53:6, 733-753, DOI: 10.1080/10643389.2022.2084315

- ^

Ministry of Human Resources. (2010). Industry Code of Practice on Indoor Air Quality 2010. Retrieved February 2024, from https://www.dosh.gov.my/index.php/legislation/codes-of-practice/chemical-management/594-02-industry-code-of-practice-on-indoor-air-quality-2010/file

- ^

Ministry of Human Resources. (2021). Guidance Note for Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) during Pandemic COVID-19. Retrieved February 2024, from https://www.dosh.gov.my/index.php/list-of-documents/osh-info/chemical-management-1/promotional-materials/4068-guidance-note-on-ventilation-and-indoor-air-quality-iaq-during-pandemic-covid-19/file

- ^

Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Greenpeace Malaysia. The Health & Economic Impacts of Ambient Air Quality in Malaysia. Retrieved February 2024, from https://energyandcleanair.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/HIA_AmbientAQ_Malaysia-FINAL.pdf

Executive summary: An editorial was published to raise awareness among Malaysians about the importance of indoor air quality (IAQ) for public health and pandemic protection, aiming to motivate behavioral change and policy improvements despite limitations and challenges.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.