TLDR: Our method can be used to compare the cost-effectiveness of new behavioral interventions that haven’t been deployed yet against established charities.

As proof of concept, we applied the general method described in the previous post to predict how cost-effective it would be to scale up an existing intervention for promoting prosocial behavior (Baumsteiger, 2019) via online advertising. Baumsteiger (2019) developed an online intervention for fostering the development of a prosocial identity and prosocial habits in high school and college students. The first part of this intervention combines information on the benefits of engaging in prosocial behavior for one’s own well-being with an elevating video. The second part guides participants to reflect on what they are grateful for, who inspires them, what they value, who they want to be, and how they would like to make the world a better place. In the second part of the intervention, participants are guided to formulate concrete plans for how to help other people on each of the following ten days. In the third part of the interventions, participants execute those plans and write about what they did to help others and how this prosocial behavior affected their well-being and the well-being of others.

Baumsteiger (2019) delivered her intervention through online surveys. This makes it very cheap to deliver this intervention to a potentially large number of people. In Baumsteiger’s experiment, links to the study materials were posted on course websites, and the participating college students were offered course credit. However, given that engaging in prosocial behavior boosts people’s happiness (Aknin et al., 2012), it might be possible to use online advertising to market this intervention as a free, short, interactive course for becoming happier through gratitude, purpose, and kindness. Supporting this possibility, thousands of people already spend considerable amounts of money on other positive psychology exercises (Horowitz, 2018).

Baumsteiger evaluated her intervention’s effect on prosocial behavior and psychological variables that promote prosocial behavior in a small randomized controlled trial with 30–40 participants per condition. She found that her intervention significantly increased the frequency of prosocial behavior immediately after the intervention and one month later. However, she did not measure the intervention’s effect on the community’s well-being, and she also did not attempt to estimate her intervention’s cost-effectiveness.

Methods

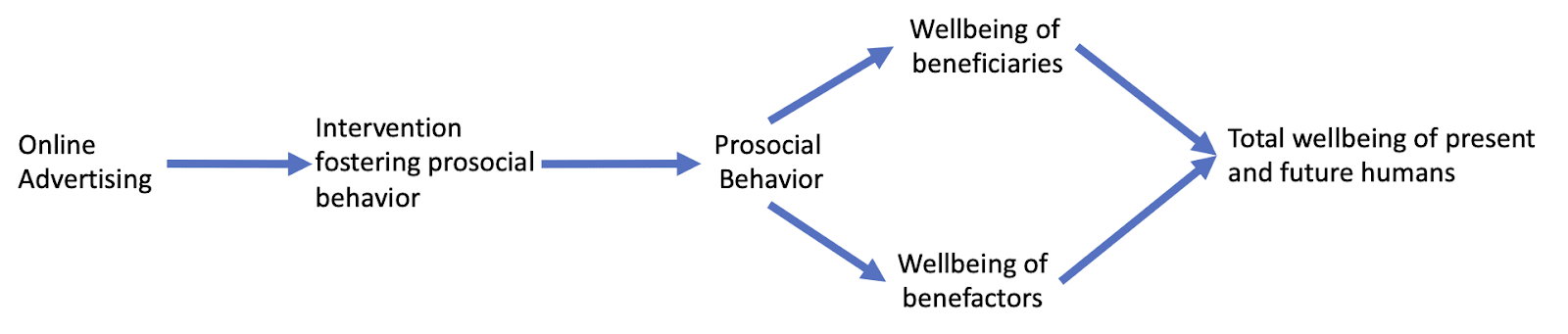

We applied the method described in the previous post to predict how cost-effective it would be to deploy Baumsteiger’s intervention through online advertising. Figure 1 shows a high-level overview of our evidence-based probabilistic causal model of the intervention’s effect on well-being. The assumed pathway to impact starts with the assumption that online advertising causes people to encounter the intervention and that some people encountering the online intervention will complete it. Because of this intervention, some people will engage in more prosocial behavior in the following weeks and months. Each time a person engages in helping, this increases their well-being and the well-being of the people they helped. Summing up the increased well-being across people and time then yields the intervention's total positive social impact. We estimated the strength of each effect along this causal pathway from the effect sizes reported in relevant empirical studies or meta-analyses. The cost of the intervention per person who completes it was estimated from empirical data on the cost of online advertising and the proportion of people who follow through with their chosen digital interventions. Moreover, we rigorously quantify the uncertainty inherent in each of these estimates and propagate that uncertainty through the causal model. This allows us to rigorously quantify the uncertainty about the intervention’s cost-effectiveness as a probability distribution. This post only gives a short, incomplete, high-level overview. If you would like to know more, you can read the detailed report and look at the model here: https://observablehq.com/@falk-lieder/cea-baumsteiger

Figure 1. A causal model of how the intervention by Baumsteiger (2019) increases overall welfare.

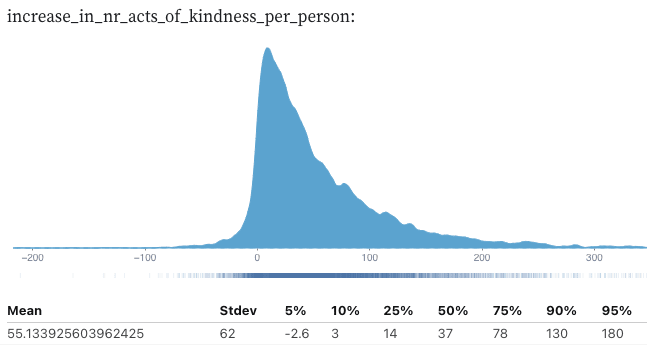

Our estimate of how much the online intervention will increase the frequency of prosocial behavior is based on the findings by Baumsteiger (2019). Based on her findings, we assume that the intervention’s initial effect is to increase the frequency of prosocial behavior by about one additional act of helping every second day (0.6 acts/day). We estimated the rate at which this initial increase in prosocial behavior vanishes from the decline observed in Baumsteiger’s original study.

Whenever a person engages in well-being, they experience a brief boost of positive emotion. We estimated the size of the boost from the meta-analysis by Curry et al. (2018). Each act of helping also increases the well-being of the person being helped. We estimated the size of this effect from experiments on the effects of kindness (Pressman, Kraft, & Cross, 2015; Zhao & Epley, 2021). How much well-being these positive emotions confer depends on how long they last and how their intensity changes over time. To capture this, we model the time course and duration of these emotional experiences according to empirical data from research emotional dynamics (Verduyn et al, 2009, 2011).

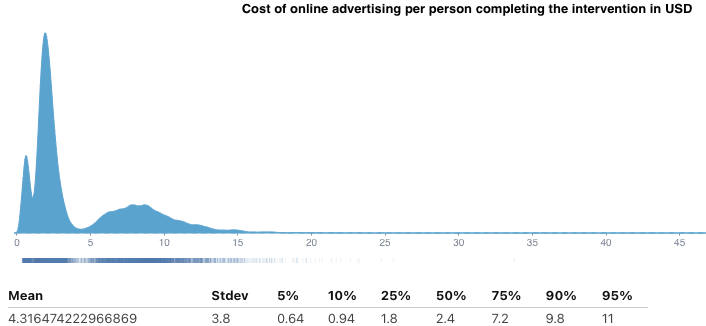

We model the cost of the intervention per person who completes it according to how much money one typically has to spend on online advertising per customer who installs the advertised app (Dogtiev, 2023) and the proportion of people who complete a digital intervention once they have started it (Meyerowitz-Katz et al., 2020). To obtain an estimate of the cost-effectiveness, we divided the sum total of the increase in well-being per person who completes the intervention by the predicted cost of online advertising per person who completes the intervention. This yields an estimate of the intervention’s cost-effectiveness in well-being-adjusted life years (WELLBYs) per dollar.

Results

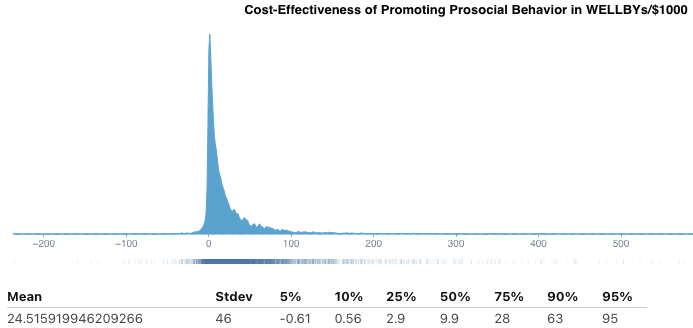

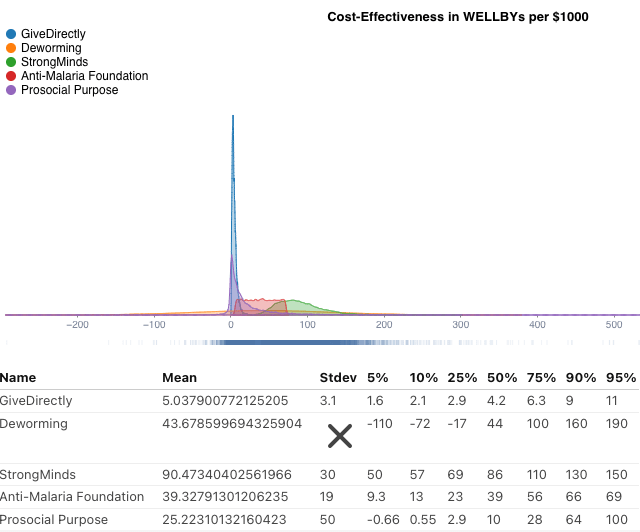

We found that the intervention's expected cost-effectiveness is about 26 hours of happiness for every dollar invested in its deployment (95% CI: [-0.6,90]). This corresponds to about 24.5 Wellbeing Adjusted Life Years (WELLBYs) per $1000 (95% CI: [-0.5,88]). These estimates were derived by dividing the average amount of well-being that the intervention might create per person reached by the amount of money that one would have to spend on online advertising to reach millions of people. The figures below show how likely the intervention would achieve different levels of cost-effectiveness according to our model. The plot shows the probability (y-axis) of different levels of cost-effectiveness (x-axis). The table below each plot summarizes this probability distribution in terms of its expected value (Mean), standard deviation (Stdev), and its percentiles.

The expected benefit of the intervention is to inspire each person who completes it to perform 55 additional acts of prosocial behavior throughout their life. Together, these 55 acts of kindness are predicted to generate 53 hours of happiness. This includes 13 hours of happiness experienced by the person performing the prosocial behavior (14 minutes of happiness per act) and 40 hours of happiness experienced by the people who benefit from those additional acts of kindness (43.7 minutes of happiness per act).

The expected cost of deploying the intervention is about $4.32 per person who completes the intervention. This cost could likely be significantly lower if the online advertising campaign focussed on regions where online advertising is less expensive.

Next, we compare the predicted cost-effectiveness of Baumsteiger's intervention for promoting prosocial behavior to the cost-effectiveness of the best existing charities, according to GiveWell and the Happier Lives Institute, according to Plant (2022). Those charities provide task-shifted interpersonal group therapy for perinatal depression to women in Africa (StrongMinds), distribute bednets to protect people in Africa from malaria (Against Malaria Foundation), distribute deworming pills (SightSavers' deworming program), or transfer cash directly to the global poor (GiveDirectly). As illustrated in the figure below, we found that the expected cost-effectiveness of the new intervention for promoting prosocial behavior (24.5 WELLBYs/$1000) is about 5 times as cost-effective as direct cash transfers to the global poor (GiveDirectly; 5 WELLBYs/$1000; 95% CI: [1.7,11]). However, it is NOT expected to be as cost-effective as the charities recommended by GiveWell or the Happier Lives Institute (Plant, 2022). Concretely, its predicted cost-effectiveness is only about one-third as high as the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds (90 WELLBYs/$1000; 95% CI: [50,150]) and only about 60% as high as the cost-effectiveness of the Against Malaria Foundation (39 WELLBYs/$1000; 95% CI: [9,69]) and the best deworming charities (43.6 WELLBYs/$1000; 95% CI: [-110; 190]).

The uncertainty about the cost-effectiveness of the new intervention for promoting prosocial behavior is very high (SD: 54, 95% CI [-0.54, 100]). This means there is a more than 5% chance that the cost-effectiveness of the new intervention could be higher than the expected cost-effectiveness of the best existing intervention (StrongMinds).

Discussion

The purpose of this post was to illustrate that our rigorous method makes it possible to predict the cost-effectiveness of new interventions for inspiring others to do more good. Our results suggest that promoting prosocial behavior through scalable online interventions could be a cost-effective way to increase well-being. We, therefore, believe that this potential cause area is worthy of further investigation. The method we used to obtain these results extended standard cost-effectiveness analyses in three crucial ways: First, it predicts the cost-effectiveness of an intervention that has never been delivered at a large scale. Second, it quantifies the uncertainty about the intervention’s cost-effectiveness in a highly principled manner. Third, while most previous cost-effectiveness analyses assessed different ways of doing good directly, we assessed the indirect route of inspiring others to do more good. Our analysis, thus, provides proof of concept that it is possible to predict the cost-effectiveness of activities that improve social welfare indirectly by changing other people’s behavior. This post only provides a very short summary. If you want to know the details and see the underlying model and analysis, you can look at the Observable notebook we used to create this analysis.

The seeming reasonableness of our method’s predictions offers hope that it is feasible to predict the cost-effectiveness of trying something new. With that said, we still need to thoroughly validate our method. To achieve that, we will test its predictions against hard empirical data on how cost-effective the analyzed interventions are in the real world. This could be done in two ways. The first approach is to test our method’s predictions for new interventions by conducting randomized controlled trials that measure the cost-effectiveness of those novel interventions for the first time. A second and less expensive approach is to apply our method to predict the cost-effectiveness of interventions that have already been evaluated from the data that was available before their cost-effectiveness was measured in the real world.

In addition to this rigorous evaluation, we plan to apply our method to identify other potentially highly cost-effective interventions that have not been evaluated yet. The tools we have developed can also be extended in other promising directions. For instance, our predictive cost-effectiveness analysis methods could be extended to promoting effective altruism, developing new interventions, and evaluation research. In the following three paragraphs, we briefly outline these three future directions.

One shortcoming of Baumsteiger’s intervention is that it does little to direct people toward effectiveness. Therefore, interventions specifically designed to promote effective prosocial behaviors – such as effective altruism – could be substantially more cost-effective (Mcclements, 2022; 10xRational, 2022). Such activities include promoting effective altruism through community building, advocacy, and media campaigns, as well as career advising, educational interventions, such as moral education (Kohlberg, 1975) and service learning (Astin et al., 2000), and good parenting (Spinrad & Gal, 2019).

A preliminary coarse-grained analysis (10xRational, 2022) suggested that certain movement-building activities (i.e., organizing 1-on-1 events for engaged EAs) may be much more effective than others (spreading EA through large events). However, the analyzed approaches can be pursued through many different strategies. Some specific strategies for persuading someone to engage with effective altruism in a 1-on-1 conversation may be much more effective than others. Drawing on the rich literature on promoting prosocial behavior (Laguna et al., 2020; Mesurado et al., 2019; Shin & Lee, 2021) and cultivating changemakers (Reynante et al., 2022) might allow us to discover highly effective strategies for promoting prosocial behavior that the EA community hasn’t considered yet.

If we were able to measure the cost-effectiveness of alternative movement-building activities, we might find that some of them are a thousand times more cost-effective than others. If we knew what they are, we could invest our resources more effectively.

Unfortunately, there are currently no established, easy-to-use methods for predicting and comparing the cost-effectiveness of the kinds of movement-building activities that are commonly proposed to foundations such as Open Philanthropy or the EA Infrastructure Fund. Our model could be a helpful starting point for developing such methods because it has several reusable components and is highly extensible. This line of work could provide community builders, donors, and funders with software tools for making probabilistic forecasts about the cost-effectiveness of alternative activities that could be pursued to promote effective altruism and other potentially impactful prosocial activities.

Baumsteiger (2019) developed her intervention in only eight months. This was one of the first attempts to promote the development of prosocial habits and a prosocial identity with an online intervention. So, there is still substantial room for improvement. These two facts suggest that developing new interventions for promoting prosocial behavior could be highly cost-effective. However, current methods are insufficient to quantify this intuition. We are currently extending our method to make it possible to quantify the cost-effectiveness of developing more effective interventions. We will share the results in one of the following posts in this series.

Our analysis indicated that there is still a lot of uncertainty about the cost-effectiveness of promoting prosocial behavior. Based on our findings, it is possible this intervention could be as cost-effective as the best GiveWell charities. Whether this prediction is correct is an open empirical question that can be answered by running an RCT. Is it worth running an RCT to find out? In our next post, we extend our method to try to answer that very question.

References:

- Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., & Norton, M. I. (2012). Happiness runs in a circular motion: Evidence for a positive feedback loop between prosocial spending and happiness. Journal of happiness studies, 13, 347-355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9267-5

- Astin, A. W., Vogelgesang, L. J., Ikeda, E. K., & Yee, J. A. (2000). How service learning affects students. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute.

- Baumsteiger, R. (2019). What the world needs now: An intervention for promoting prosocial behavior. Basic and applied social psychology, 41(4), 215-229.

- Curry, O. S., Rowland, L. A., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 320-329.

- Dogtiev, A. (2023). Cost Per Install (CPI) Rates (2023). Business of Apps. https://www.businessofapps.com/ads/cpi/research/cost-per-install/ Online resources accessed on February 8, 2023.

- Horowitz, D. (2017). Happier?: the history of a cultural movement that aspired to transform America. Oxford University Press.

- Kohlberg, L. (1975). The cognitive-developmental approach to moral education. The Phi Delta Kappan, 56(10), 670-677.

- Laguna, M., Mazur, Z., Kędra, M., & Ostrowski, K. (2020). Interventions stimulating prosocial helping behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50(11), 676-696.

- Lieder, F., Prentice, M., & Corwin-Renner, E. R. (2022). An interdisciplinary synthesis of research on understanding and promoting well-doing. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(9), e12704. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12704

- Mesurado, B., Guerra, P., Richaud, M. C., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2019). Effectiveness of prosocial behavior interventions: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update: From Translational Research to a Humanistic Approach-Volume III, 259-271.

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G., Ravi, S., Arnolda, L., Feng, X., Maberly, G., & Astell-Burt, T. (2020). Rates of attrition and dropout in app-based interventions for chronic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e20283.

- Plant, M. (2022). Don’t just give well, give WELLBYs: HLI’s 2022 charity recommendation. Effective Altruism Forum, https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/uY5SwjHTXgTaWC85f/don-t-just-give-well-give-wellbys-hli-s-2022-charity

- Pressman, S. D., Kraft, T. L., & Cross, M. P. (2015). It’s good to do good and receive good: The impact of a ‘pay it forward’style kindness intervention on giver and receiver well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(4), 293-302.

- Reynante, B. M., Wilcox, J. E., Stephenson, O. L., Lieder, F., & Lacopo, C. (under review). Cultivating Changemakers: A review of Metachangemaking.

- Shin, J., & Lee, B. (2021). The effects of adolescent prosocial behavior interventions: a meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22, 565-577.

- Spinrad, T. L., & Gal, D. E. (2018). Fostering prosocial behavior and empathy in young children. Current opinion in psychology, 20, 40-44.

- Verduyn, P., & Brans, K. (2012). The relationship between extraversion, neuroticism and aspects of trait affect. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(6), 664-669.

- Verduyn, P., Van Mechelen, I., Tuerlinckx, F., Meers, K., & Van Coillie, H. (2009). Intensity profiles of emotional experience over time. Cognition and Emotion, 23(7), 1427-1443.

- Zhao, X., & Epley, N. (2021). Insufficiently complimentary?: Underestimating the positive impact of compliments creates a barrier to expressing them. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 239

Thank you for writing this article! It's really interesting to see this evaluation of the costs and benefits of the intervention.

Milli Martin - the intervention is currently being tested as a part of a larger investigation aimed at helping people with adverse childhood experiences, as Falk mentioned below. I'm also piloting a briefer (4-day) version and hoping to apply for funding to test it in a more diverse population.

Thank you very much for the interesting case study. It not only gives good insight into your method, but also showcases a promising intervention.

Do you know what the current state of it is? Is it being developed further? Is it looking for funding?

I'm confused by "Anti-Malaria Foundation". Do you mean "Against Malaria Foundation" or is this an organization I'm not aware of?

Rachel Baumsteiger continues to conduct research on the intervention for promoting prosocial behavior. The intervention is currently being deployed by the University of California as a mental health service for students with adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress. This will yield some additional data on its benefits and effectiveness. However, because this deployment is funded as a mental health service, it doesn't include a control group. Running a rigorous, large-scale RCT will require additional funding. In a later post, I will show that doing so would be highly cost-effective. I think if funding became available, Rachel Baumsteiger would be happy to run the RCT. And I know that I would be excited to collaborate on that project.

"Anti-Malaria Foundation" was a typo. I have corrected it to "Against Malaria Foundation".